Every month in PC Gamer magazine we run a section called Now Playing, in which we recount the gaming adventures we've enjoyed that month. This edition features a fun mix of stealth, horror, surreal weirdness, and good old fashioned Star Wars nostalgia.

Joanna Nelius - Gylt

If you’ve ever had a nightmare about your hometown turning into something macabre and barely recognisable, that’s Gylt. The town is devoid of life. Abandoned cars litter the cracked and crumbling streets. Humanoid monsters with boils on their black skin wait for you around every corner. And you play as a little girl named Sally in this Stranger Things-esque world trying to save your cousin, Emily, from the creatures hell-bent on destroying her and you.

Gylt is a Google Stadia exclusive that I’ve been chipping away at ever since I completed my review for the platform back in November. You can buy it and play it with Stadia's free version, which includes a two month trial of Stadia Pro. Tequila Works currently has no plans to bring its game to other platforms, so if you have a gaming PC and don't need to stream it, you unfortunately can't choose to run it locally.

Gylt is a well-balanced mix of stealth, puzzle solving, and direct confrontation, with a good story. Your flashlight is your most trusted resource for popping giant eyeballs and fighting off monsters, but there are also strategically placed vending machines that dispense free soda should you want to try the old ‘look over there’ trick. It’s not a complex game by any means, but it’s thick with tension and a few jump scares—though nothing that will induce a heart attack, as it’s more of a horror-lite experience.

Gylt is a game about what it’s like to be bullied. The school, where you spend most of your time searching for Emily, is a grim visualisation of just that. At a table in the back of the cafeteria there are a few mannequins posed around one sitting on the bench, pointing and laughing at it. Classrooms are filled with red and black graffiti taunting you to ‘get lost’ and ‘don’t tell’. And as you get closer to finding Emily, you can make out words in between her screams.

For me, it was the moments I spent crouched behind a desk that made me remember the time I would try to avoid the kid who liked to bully me during break time. I would hide in the bathroom or try to sit close to the playground supervisor. Gylt plays up the terror of being a child who gets made fun of every day, but it also does more than that—it drives home the importance of standing up for the kid who is bullied. The idea of fighting off the monsters (aka the bullies) with light is romanticised, but you are the only one who is coming to Emily’s rescue – and sometimes all it takes is one person to stand up for someone else. Yes, it’s scary, but it’s the heroic thing to do.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Stadia's free version was not yet available, but it launched on April 8.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Robin Valentine - Six Ages: Ride like the Wind

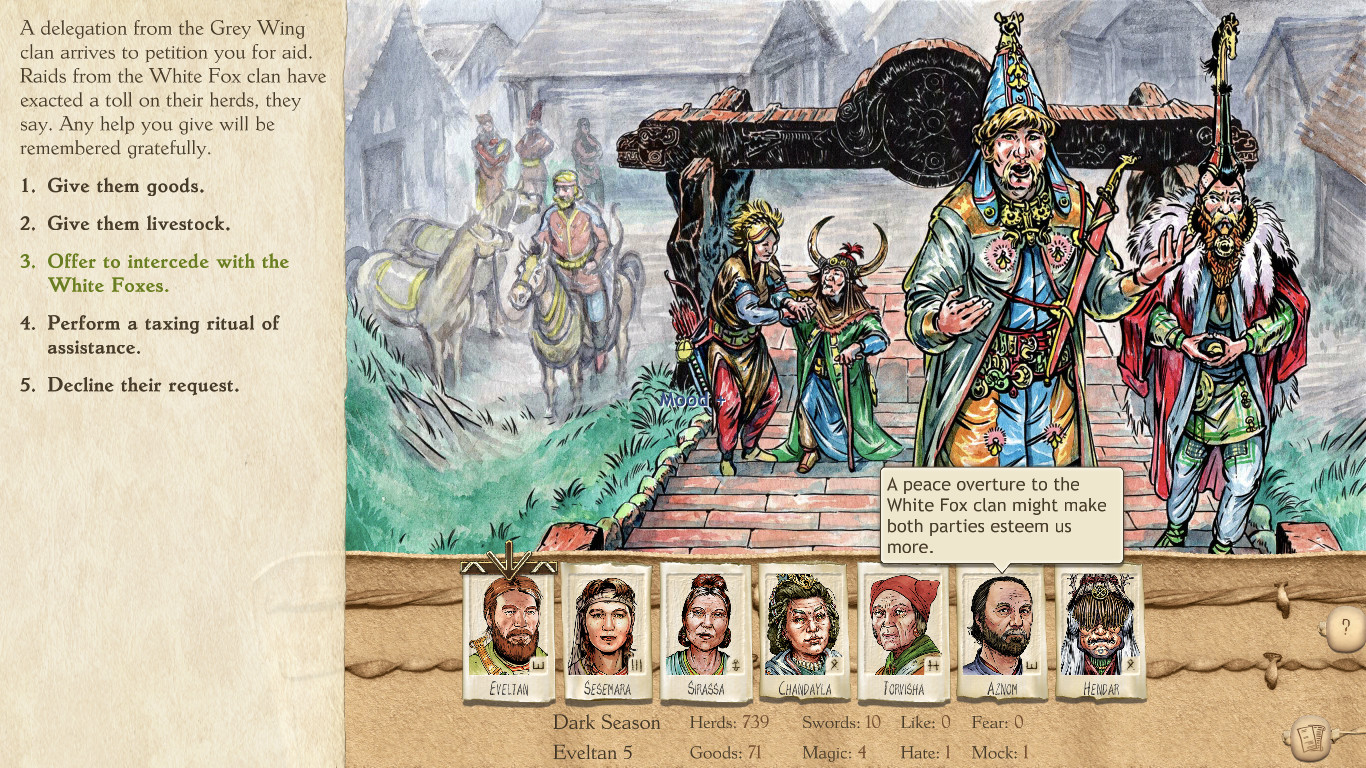

From the very first moments, this largely text-based game puts me on the back foot. Superficially, it’s a game about managing a settlement in a fantasy land, making sure all of your citizens are safe, warm and well-fed. But almost immediately, it reveals itself to be much stranger than that implies.

Before you even begin, you have to choose an origin story for your clan, picking from multiple options at different points in their history. These choices are largely baffl ing, steeped heavily in the game’s unique setting. I scrape together crumbs of lore as I go – gods are very real, their power can be invoked by physically reenacting old myths, but most of them are asleep I think? And my clan’s patron deity is the god of a specific species of beetle used to make red clothing dye?

As I get into the game proper, it becomes clear that more than being a challenge of farming, building, and the rest, it’s an ongoing test of how well I can understand and work within a culture totally unlike my own. Events are triggered as I play, in which something happens and I’m invited to make a choice about it. Far from being familiar moral decisions, they frequently revolve around the clan’s very specific customs and traditions, and how they apply to often bizarre situations. AGE APPROPRIATE What’s the least embarrassing way to disperse a fl ock of magical birds that keep whispering in your shaman’s ear? Is a polished buzzard beak an appropriate bride-price? How many cows is a fair exchange for the spirit of a sabre-toothed tiger? Fair questions. I wish I knew the answers.

I won’t lie, it’s overwhelming. But at the same time, such a commitment to its weird world is refreshing.

To my mind, videogames are in dire need of more strangeness. For a medium so steeped in sci-fi and fantasy, and where the impossible takes no more effort to represent than the real, it’s disappointing to me how much time we spend stuck with tired old tropes. Shooting zombies, chopping up orcs… repetition has made the fantastical bland.

So while I am struggling to get to grips with it, I’m also intrigued. Given the choice of learning the backstory behind yet another war between the forces of light and darkness, or figuring out the correct wife-tobuzzard-beak exchange rate, I know where I want to spend my time.

Steven Messner - Escape from Tarkov

I am not a brave man. Where Escape From Tarkov’s battle-hardened veterans will actively look for a fight, I fl inch at even the most distant sounding gunshots, scurrying from bush to bush and outright avoiding the most well-trafficked areas unless I absolutely have no choice. In the grand food chain of Escape From Tarkov, a hardcore mil-sim survival shooter about looting gear in a post-apocalyptic Russian city, I am not a bear or a tiger. I am a rat, feasting on the remains left behind by more skilled players. And I kind of like it that way.

Though Escape From Tarkov has much in common with both survival games like DayZ and battle royales such as PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, it manages to feel like some kind of mutant hybrid between the two. I still slink through bushes, intently listening for the sound of nearby players who will certainly try to kill me and take all my gear, but instead of taking place in a persistent open world, Tarkov drops you into smaller maps and gives you a time limit to reach the opposite side. If you make it out alive, you get to keep everything you found to use in the next round. It reminds me a bit of EVE Online, where I’m constantly gambling my best equipment and hoping I live to fight another day. Often I don’t.

But when I do it’s almost always because I channelled my inner rat. I stick to the shadows, letting players kill one another off and take the best loot, and then I make my move.

It’s a playstyle that would never work in DayZ or PUBG, where the map is either too large to reliably find other players or the main objective is to be the last man standing, so I might as well be aggressive about it. But in Tarkov, one of my favourite things to do is camp in the exfiltration zones and ambush players just as they think they’re so close to safety. I’m a bit of a diabolical asshole, but the sheer joy of letting someone else do all the looting only for me just to take it from them at the last possible moment is too sublime not to indulge in.

Just behind the three-story dorms on Customs is my favourite spot. Here, players can pay 7,000 rubles to exfiltrate to safety, which is a hell of a deal considering the dorms are one of the best loot spots on the map. Players get in, clean it out, and then only have a 30-foot jog to the exit. But that’s exactly where I wait. Tucked behind a tree, sights pointed on the doors that open towards the exfiltration zone.

Just as the timer begins to run low is when players drop all semblance of caution and sprint for the exit, and just as they’re so close—30 minutes of effort well rewarded—I pop them in the skull and take everything.

It’s certainly not the most honourable way to make a living in Tarkov, but I’m so flush with rubles I don’t even care.

Matt Elliott - Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order

Liking Star Wars is like being the coveted child in a custody battle. My Last Jedi dad insists the things I love are bad for me and has replaced my Coke with kombucha. My Rise of Skywalker mum is responding by feeding me energy drinks until I resemble a taurine-fattened mallard. I loathe them both. Can Fallen Order fix me?

Not initially. It won’t launch on Steam, so I have to download it twice and try again with Origin open—the sort of frustrating false start that feels like trying to tear a new sheet on cheap toilet roll. It works eventually—I have no idea how—and Fallen Order finally gets off to the start I longed for. Stirring music, twisted metal structures, and soaring flybys all make me realise how low my bar is when it comes to Star Wars. Show me some mangled Venator-class Star Destroyers and I’m entranced; drop in a Seperatist Control Ship and I’m yours forever. It’s a properly brilliant intro: sweeping and cinematic, with enough narrative set-up to make me care about Cal having to leave his old world behind. I can even forgive the use of "Press [F] to use The Force", perhaps the clumsiest on-screen prompt since we all paid our respects in Advanced Warfare.

So far, so wonderfully daft. The environment shears and collapses in a way that always leaves me with something to climb—perhaps that’s The Force – and Stormtroopers panic as I hack them down. But it’s also stern. Melee combat is punishing when I get the timing wrong, and that makes things more rewarding when they go right. The combat is flashy enough to make Darth Maul look like a wheezy pensioner, and there’s nothing quite like deflecting blaster bolts back at grunts dim enough to shoot at me. I already feel like a Jedi—albeit a bit more like the work experience Padawan who still has to serve the masters blue milk.

I just want to guzzle it all down like a rich cosmic smoothie. I love locking lightsabers with the Imperial Inquisitor. I take the time to stop and listen to the sound of the alarms of Rebel spaceships—gentler than their Imperial counterparts ("Yes, we are going to die, but please try not to panic"). And I devour all the little touches that feel like the work of informed, invested creators. How come no game until now has let me light dark places with my lightsaber? I can even forgive Cal for crimping out melodies on a hallikset.

Most of all, there’s a sense that however much I love or hate what Star Wars is doing at the cinema, there’s enough care and attention elsewhere to make me forget. KOTOR was my first proper experience of the expanded universe, and while I don’t feel like I’ve come full circle with Fallen Order, it’s good enough to make me realise it’s the operatic sci-fi world I love most.

The collective PC Gamer editorial team worked together to write this article. PC Gamer is the global authority on PC games—starting in 1993 with the magazine, and then in 2010 with this website you're currently reading. We have writers across the US, UK and Australia, who you can read about here.