How Monster Hunter rose from niche import to an international sensation

A brief history of the series in the East and the West through the eyes of a hunting veteran.

This article was originally published in 2018 in the lead up to the launch of Monster Hunter: World, the first game in the series on PC. We're republishing it now to look back on Capcom's journey as Monster Hunter Wilds draws near.

I remember the day Capcom first showed us what would eventually be known as Monster Hunter. It was 2003, at the then-annual Capcom Media Day in Las Vegas, and of all the games they showed us that day, Monster Hunter stood out. There was the GameCube's Viewtiful Joe and P.N.03, and PS2's Devil May Cry 2, but I couldn't tear my eyes off this curiosity called Monster Hunter. We watched a CGI cinematic of what appeared to be a four-player cooperative multiplayer game, in which the squad would customize and optimize its gear to take down powerful monsters. I needed this. Badly.

When I first learned about Monster Hunter, I was a grieving Phantasy Star Online widower.

You have to understand that when I first learned about Monster Hunter, I was a grieving Phantasy Star Online widower. Earlier that year, SEGA bafflingly decided that what the PSO fanbase really wanted was a card game, not more of the then-peerless Diablo-lite loot action I'd been hopelessly addicted to. A card game. I wanted none of that, and apparently neither did many other people, as that was basically the end of the PSO franchise. But suddenly, Capcom had something that looked like it could fill that void.

The monster theme felt fresh, and between the beautifully designed characters and variety of weapon types, this looked like a major hit brewing. Capcom showed us plenty of other games, but Monster Hunter was all I wanted to know about. I expected plenty of button-mashing and sword swinging, but the dev team had other ideas. The producer who took the podium said that instead of using the usual button schemes to attack, weapon moves would be mapped to the right-analog stick to simulate the heft and feel of a broadsword.

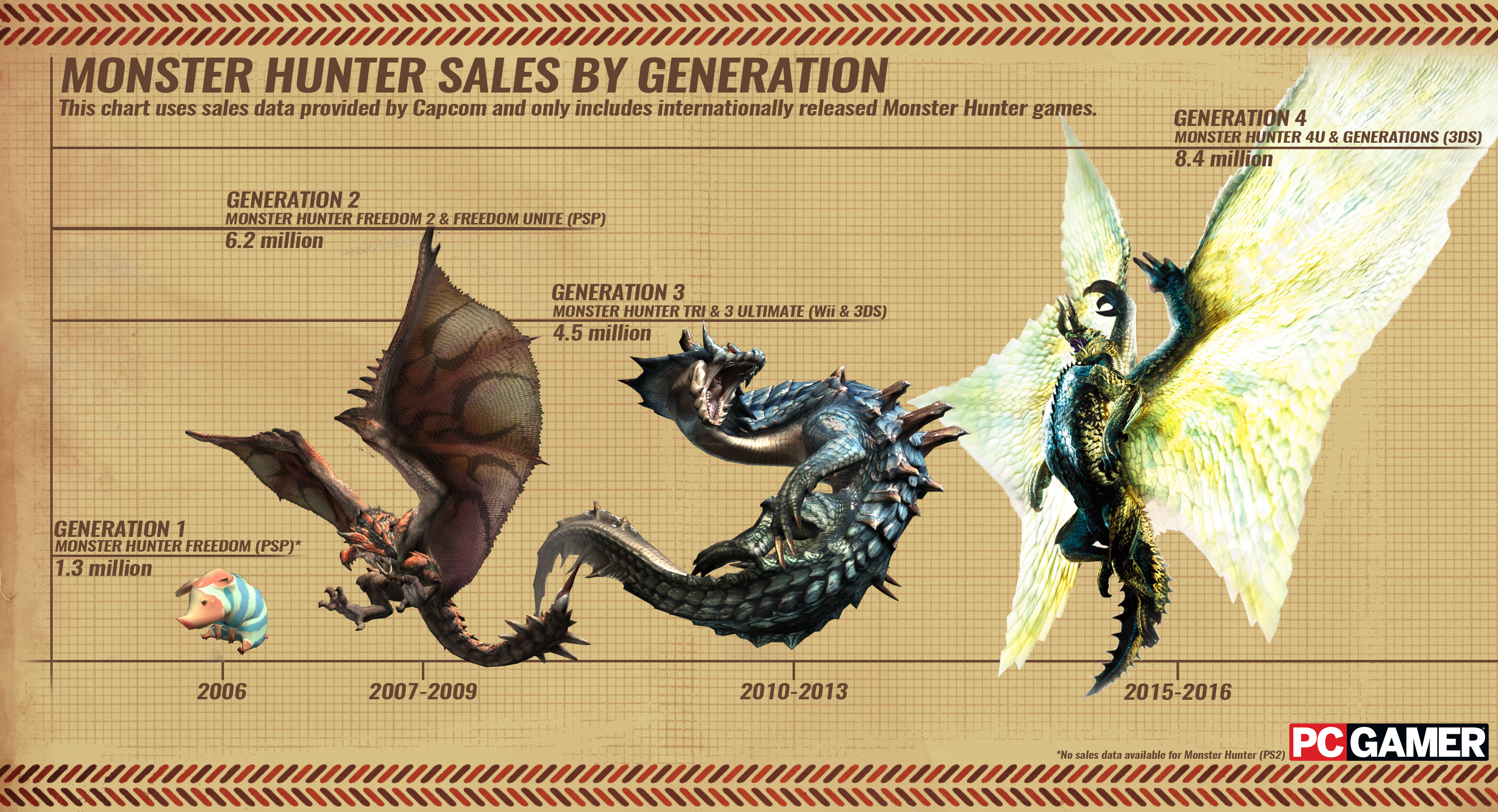

As progressive as this idea was, the execution was weak, and the game was not a hit when it came out in 2004. Whether it was the basic concept or the actual hands-on experience, the first Monster Hunter just didn’t click with the masses, and the next couple of expansions and sequels would stay in Japan. It wasn’t until Monster Hunter Freedom 2 that we’d get another taste.

Fifteen years later, it's almost inconceivable Monster Hunter was ever small time. How did it become such a juggernaut in Japan, and after a lifetime mostly stuck on handhelds like the PSP and 3DS, ship more than five million copies on consoles with Monster Hunter World in just three days?

What makes Monster Hunter: World any different? Why should this be the one to elevate monster hunting to a new obsession on console where past efforts have failed? After playing Monster Hunter since the very beginning, in the US and Japan, I know all about its missteps and triumphs, and why all of the pieces Capcom's put on the board over the past 15 years have finally aligned for Monster Hunter to have its moment in the West—and, at long last, on PC.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Let the hunt begin

In the US, going over to a friend’s house requires driving and that right there is enough to change the dynamic of playing Monster Hunter into... not playing Monster Hunter.

Monster Hunter Freedom 2 (Monster Hunter Portable 2nd in Japan), released three years after the original, is where things took off. The unusually detailed graphics were an attention grabber on the PSP, but it was the PlayStation Portable’s ad-hoc four-player action that was the real game-changer. While the first Monster Hunter for PSP sold a little over a million copies, the sequel nearly doubled that amount. Critically, the results were inverted. The review scores in the West averaged in the low 80s for the first PSP offering, but dipped down to the 70s for the second, with the main critique that it was more of the same, but to the gamers that cared about Monster Hunter, this was precisely what they wanted: More loot, more things to hunt, more ways to kill time (and monsters) together.

This is why I love Monster Hunter. I mostly lost interest in single-player RPGs a long time ago. The thought of sticking with a pre-baked character that I don’t identify with (sorry, Tidus) for the better part of 90-100 hours, with no visible changes in the gear I work super hard for, well, that doesn’t have a lot of appeal for me. I prefer games where you work hard and play hard (I spent a decade playing Final Fantasy XI) and you are able to showcase the rewards you’ve reaped.

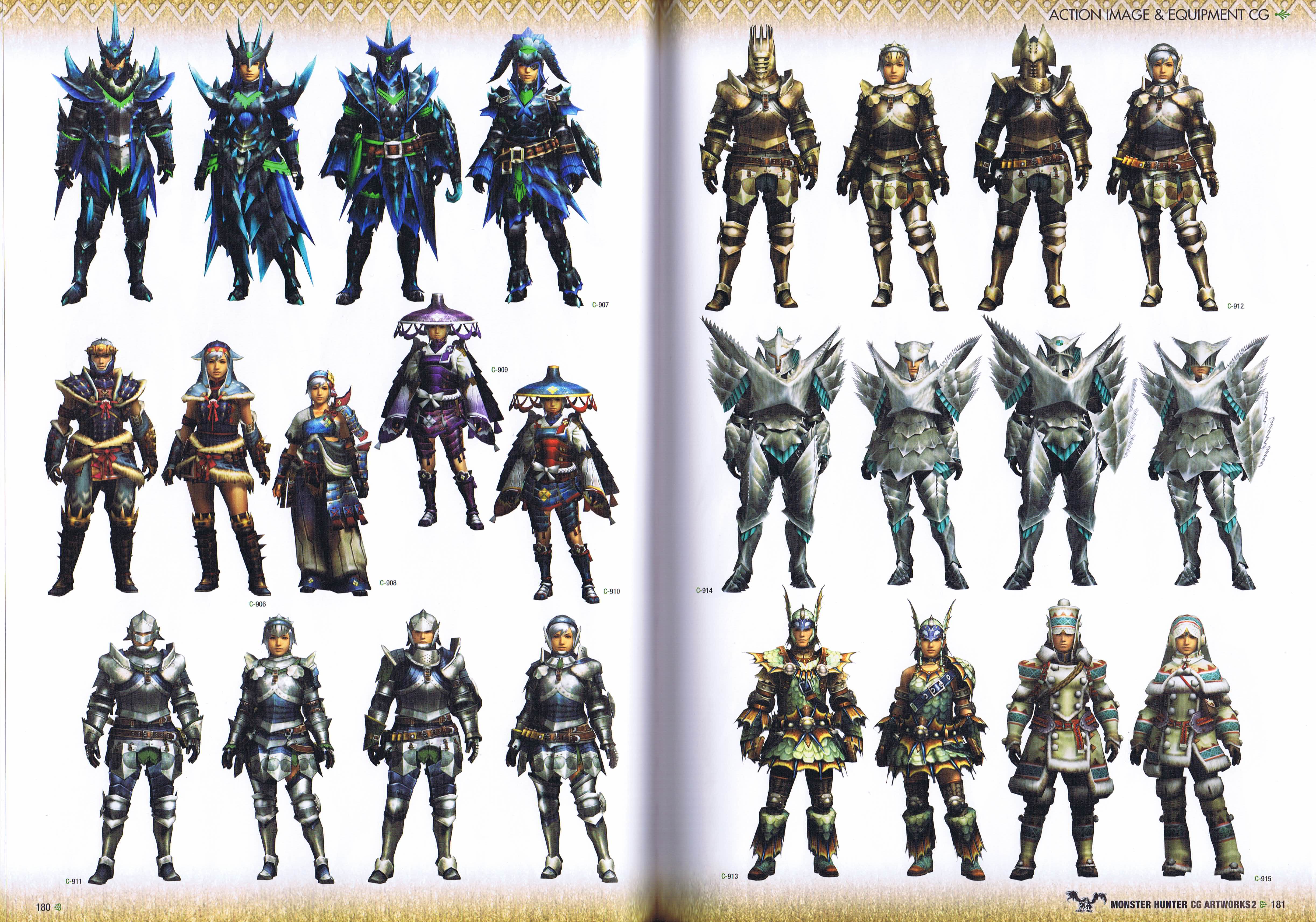

In the 8- and 16-bit days, we were limited by what the tech could provide. But once Diablo 2 unleashed its sweet, sweet game loop, letting me customize my little sprite with endless armor and weapon combinations, and reflected these changes on my character, it’s all I’ve wanted ever since. Then came Phantasy Star Online, and then Final Fantasy XI. I really like the Japanese character design; it’s more graceful, elegant, and less beholden to Dungeons & Dragons-style visual tropes than games like EverQuest. So when Capcom showed me Monster Hunter, I knew this would be a game for me. It’s tough going, but when you see a really good player in multiplayer, wearing elite gear, you know they earned it, and that’s what keeps Monster Hunter players going.

Unfortunately the advent of ad-hoc multiplayer didn’t do much for me in the US, as none of my friends or co-workers were really putting much time in on their PSPs. But thanks to a tedious half-hour morning commute on San Francisco’s 38 Geary bus line, I had a lot of time on my hands. So a-hunting I would go, solo. Through the years, each expansion and sequel would add slightly better graphics, new villages, different NPCs, tougher ranks, more gear, and—once the series hit 3DS—extensive DLC. None of this changed my monster hunting fortunes, though. I was primarily a solo hunter in the U.S. wishing I was a Japanese kid in Tokyo.

The majority of Japanese school kids live in densely populated urban environments. During my trips to Japan it was common to see four or more kids gathered under a tree by their school, outside a ‘conbini’ (convenience store), or even on a train playing Monster Hunter together. While I was running around solo on my PSP, rank 3, slowly grinding out quests, these 12 year-olds were probably taking down an HR9 Rajang like it was nothing. In the States, gamers gather online. The idea of a ‘social’ gaming experience in the U.S. is putting on a headset and getting to work, usually in physically isolated scenarios.

If anyone was in a prime position to get their hunt on, it was me, and even then I could barely scrape together a hunting party.

The days of LAN parties, where people played Quake or Halo in the same room together are, if not completely dead in the West, at least in the minority. This has been a critical factor in Monster Hunter’s early lack of success in the West. Especially in the United States, people are too spread out. In the suburbs, and pretty much anywhere outside of New York City, San Francisco, Chicago, and the major cities, going over to a friend’s house requires driving and that right there is enough to change the dynamic of playing Monster Hunter into... not playing Monster Hunter.

I mean, I lived in San Francisco and worked at a video game magazine in an office full of gamers where loads of people had PSPs. If anyone was in a prime position to get their hunt on, it was me, and even then I could barely scrape together a hunting party. At one point I even made a serious effort to take the game online, to play with desperate, like-minded gamers who all bought 3rd-party adapters, cables and apps, like Ad-Hoc Party on PS3 and Xlink Kai for PC. There were extensive FAQS on how to connect all of this to play with Japanese players over the Internet. It was way too much effort just to get a game going.

If I couldn't get regular games going with all of those advantages, what chance did the series have in catching on with the rest of the country? Even with the recent success of the latest 3DS releases, it’s never been the phenomenon here it has been in Japan. Certainly part of the game’s inability to duplicate the Japanese level of success had a lot to do with convenience, but it’s also very possible that the Monster Hunter milieu didn’t resonate with western gamers at the time, either. In a way, Monster Hunter is spartan. It has depth and replayability, but little real narrative or motivation outside of hunting for hunting's sake. So as Monster Hunter continued to grow in Japan, even console ports weren't enough to catch on in the West.

The console problem

Eventually I moved to Japan for about five years—not to play Monster Hunter, but to work for game developer Q Entertainment, though I can't deny it was a pretty sweet perk. I suddenly and miraculously had no shortage of access to skilled Monster Hunter players. One thing you can rely on with Japanese gamers is that when something’s hot, everyone is playing it.

By the time Monster Hunter Portable 3rd launched, the entirety of Japan was in full-on Monster Hunter mode.

Monster Hunter sessions manifested regularly during lunchtimes or after work. More often than not I actually turned down offers to play during lunch when I would have once killed for the chance to have some multiplayer action. In Japan, I was a casual participant while my co-workers were religious about going on three or four hunts per lunch hour. The hotness during my time in Japan was Monster Hunter Portable 3rd for PSP, which was—to make a broad analogy—the Street Fighter III: Third Strike of the Monster Hunter series. It was super refined, absolutely packed with content, and by this point the clear apex of the franchise.

Let me be clear about this: By the time Monster Hunter Portable 3rd launched, the entirety of Japan was in full-on Monster Hunter mode. This was, and remains, the biggest-selling PSP game ever. Clothing brand UNIQLO was selling Monster Hunter t-shirts and underwear all over Japan. Popular curry chain Coco Ichibanya were running special promotions: Buy a plate of curry and earn a chance to win a special Monster Hunter-branded spoon. TV variety shows even had Japanese celebrities of all demographics engaging in ad-hoc hunts on television. It was insane, and I was loving every minute of it.

I sorely wished that Capcom had localized Portable 3rd into English, or the gorgeous Monster Hunter Portable 3rd HD ver. for PlayStation 3. Up until then I had been using the PSP’s component cable adapter to play Monster Hunter Portable 3rd on my TV, but the PS3 version made all those cables unnecessary, and it was cross-compatible with the PSP version, which meant I could carry progress gained during lunchtime sessions over to the vastly more attractive PS3 version at home.

So, the Monster Hunter phenomenon remained largely, as they say, big in Japan. But even with the series’ massive popularity on its home turf, Monster Hunter has never, ever—in Japan or otherwise—found success on consoles the way it has in portable form. The formula has been simple: Lots of kids, dense urban areas, and ad-hoc play equal success. Anything else has simply been met with varying degrees of indifference. And it didn’t help that before World, Capcom's last console efforts like Monster Hunter Tri (Wii) and Monster Hunter 3 Ultimate (Wii U) were just uprezzed ports of previously released handheld stuff. Those were relatively minor successes, but Monster Hunter's biggest hit was still to come.

By the time the PlayStation Vita was preparing to launch in 2011, all of my “MonHan” (the common Japanese slang) group were excitedly bracing for how amazing a Vita version would look. Then Capcom flipped the script and announced that upcoming Monster Hunters would be released exclusively for Nintendo 3DS, a less powerful handheld that wasn't doing too well at the time. It was shocking but understandable.

Until the PSP, handheld gaming was dominated by one company: Nintendo. In Japan, however, the PSP ate Nintendo’s lunch, and by astounding numbers. Nintendo could not afford to let that happen again, and through what must have been some very interesting negotiations, they brought Capcom on board the 3DS in a big way, preempting the Vita launch with carefully timed hardware price drops and releasing Monster Hunter Tri G (Monster Hunter 3 Ultimate in the West) on 3DS in Japan literally one week ahead of the debut of the PlayStation Vita. Brutal. And effective.

Through the years, Capcom would re-establish the brand on 3DS, and while it was a slow-burner at first, Monster Hunter eventually regained its momentum, routinely selling in the millions, globally, on Nintendo’s handheld. As global adoption of the 3DS (a slow-burner to start) took off, so too did Monster Hunter’s fortunes. With the wind at its back, the Monster Hunter franchise is now in its best position ever to make its case as a worthwhile concern on home consoles.

A Monster Hunter for the world

When Capcom finally unveiled Monster Hunter: World, I was cautiously excited. I mean, they’d tried this before, right? And every time it was usually an uprezzed port of a game I’d played a million times before. Once I took a closer look at the details, though, I knew I had to give this a chance. First, the game was being built from the ground up for consoles and PC. This addressed the issues with Monster Hunter Tri and Monster Hunter Ultimate 3. Then, in a true first for the series, Capcom was simultaneously releasing this in all territories? It’s perhaps a small thing, but it’s important that the playerbase isn't already looking ahead to Japan's next entry when the most recent finally gets localized. And it was just so damn good looking.

For years, PC players had been pining for Monster Hunter Online to be released outside China. But here, finally, was a true Monster Hunter for PC, not an MMO spinoff.

Then the beta dropped. Wow. While the missions were very basic, and gave little insight as to how the overall game flow, mechanics, UI, and progression would manifest themselves, it was clear that Monster Hunter: World, to veterans like me, was the real deal. The beta, and now the full release have been so much fun that I may find it very difficult to go back to the handheld versions. Hopefully Capcom is taking notes, and will fold a lot of World’s advancements back into the way they develop the mechanics of the next portable iteration.

Monster Hunter: World is basically everything I’ve ever wanted in the series. Since the beginning of my time in the “MonHan” universe in 2003, I’ve often been frustrated by the franchise's seeming inability to really break away from its formula. Each sequel starts off with the same herb-gathering tedium, and as a series it’s really intimidating to newcomers. Foolishly, I even once tried to get my non-gaming wife to play the game with me. I bought her a 3DS, and a second copy of every new game that comes out. Despite my best efforts, I’ve so far failed to make it “our game.” There’s just too many systems to learn, combined with my own impatience, resulting in nothing but frustration.

After more than a decade of portable games, Monster Hunter: World looks insane.

While I don’t expect Monster Hunter: World to move the needle on my marital monster hunting, it does address a lot of the things that have held the series back on console. It doesn’t completely deviate from what’s come before, but things move a lot faster. The game immediately throws you into the action when your ship runs aground a giant monster that throws everyone on board into the sea. When you wake up on the beach, Monster Hunter: World starts tutorializing you. I hate tutorials, and thankfully you won’t miss too much if you dribble past the talky NPC's dialogue trees. The important stuff is what happens in the game proper.

After more than a decade of portable games, Monster Hunter: World looks insane. There’s just so much detail I can barely keep track of all the things on-screen, including the living creatures, the complex environment, dense foliage, and the redesigned UI. It’s a lot to take in. I can only imagine how good it’ll look running on a cranked up gaming PC. The leap in quality from 3DS to console and PC is basically like going from watching Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion classics, like Clash Of The Titans, and then seeing Jurassic Park for the first time.

The most important thing, though, is the game moves quickly, ideal for returning players or anyone put off by drawn out introductions. While NPCs still tend to blather on, once I’ve got my glaive strapped to my back and I’m running across open plains in MHW, it’s smooth sailing.

There are features we've never seen before, like hitching a ride on a pterodactyl. Instead of a map carved up into small connected sections, everything is linked in one, big, open world style. The maps are huge, but they don’t take forever to traverse. Stamina drains much less quickly than in the handheld versions (which means you can sprint for longer periods of time), climbing walls and ledges is as simple as running up to and over them, and the game is really, really vertical at times. Brace yourself for a deluge of #MonsterHunterWorld hashtags and screenshots as people snap photos from high atop a tree branch. It’s that scenic.

Capcom took a risk with with Monster Hunter: World, and it seems to have paid off enormously. While the skills of veteran players will certainly carry over from portable to console, the real test here is whether everyone else will finally embrace it. I don’t want to say it’s do or die for Monster Hunter as a console concern, but it’s clear that Capcom put a ton of effort and resources into hitting this out of the park. Now World needs to pull people away from other multiplayer games, or at the very least provide a compelling community for gamers who aren’t swayed by Call Of Duty or other run and gun shooters.

I want it to be a success, because I certainly want more of it. But I also find it interesting that in an era where publishers push season passes on you, Capcom is maintaining its stance of offering free updates for World, a practice it preaches on handheld. I’m also glad they didn’t try to bring Monster Hunter Frontier or Online—their two MMOs—over here instead, as they could've landed with such a thud the PC community would turn its back on Monster Hunter. So, if you’ve ever been on the fence about this series, now is as good a time as any to jump into the fray and grab a glaive or great katana (or switch axe if you prefer). Here be monsters—but that's the point, right?

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.