How Japan learned to love PC gaming again

Since 2010, Japan has embraced the PC. Developers talk about the challenges they overcame to make it happen.

Dark Souls changed everything. There were Japanese games on PC before Dark Souls, of course, some celebrated like indie darling Cave Story, some infamously messy, like 1998's trapezoid box Final Fantasy 7. But Dark Souls was different. It hit all of videogames like a bomb: on impact we reeled at how boldly it embraced challenge and obfuscation and how badly we had missed this particular flavor of Japanese game design. And then came the shockwave: that design seeped into the brains of players and designers and it stuck, driving a wave of games big and small inspired by the popularity and sales of this strangely new, strangely old game. PC gamers wanted in. 90,000 petition signatures later, FromSoftware said sure, we'll bring it to PC.

Dark Souls came to PC a year late and half broken, and neither of those things ultimately mattered. Today nearly three million PC gamers own Dark Souls, and that demand was a sky-piercing beacon for Japan: a whole lot of people in the West own PCs, and we want to play Japanese games on them.

Since Dark Souls in 2012 new consoles launched with hardware very similar to PCs, once-niche games like Valkyria Chronicles rocketed towards a million sales, and visual novels that would once have required fan translations plastered Steam. It's been a slow accrual of momentum, a boulder gathering speed as it prepares to tumble full-tilt downhill. Sales numbers alone weren't enough to lead to change overnight. To understand why Japanese games are now poised for a huge breakthrough on PC—and why it's taken so long for that boulder to get up to speed—I spoke with developers and publishers in the US and Japan about the rise of Japanese PC games in the West and at home.

The first obstacle to PC gaming's growth is a simple one: very few people own PCs in Japan. But there's much more to it than that. There's the challenge of using Steam in Japanese. There's the frequent need for a champion—sometimes a single person in a huge company—to boldly fight for a PC port. There's the long history of 'doujin' fan games in Japan and a struggling indie scene finally beginning to find its footing. There's a genetic predisposition to motion sickness that turns Japanese gamers away from first-person games. And there's 7-Eleven.

What the hell do convenience stores have to do with Japanese PC games? We'll get to that. But first: how Japanese games have come to thrive on Steam in the Dark Souls era.

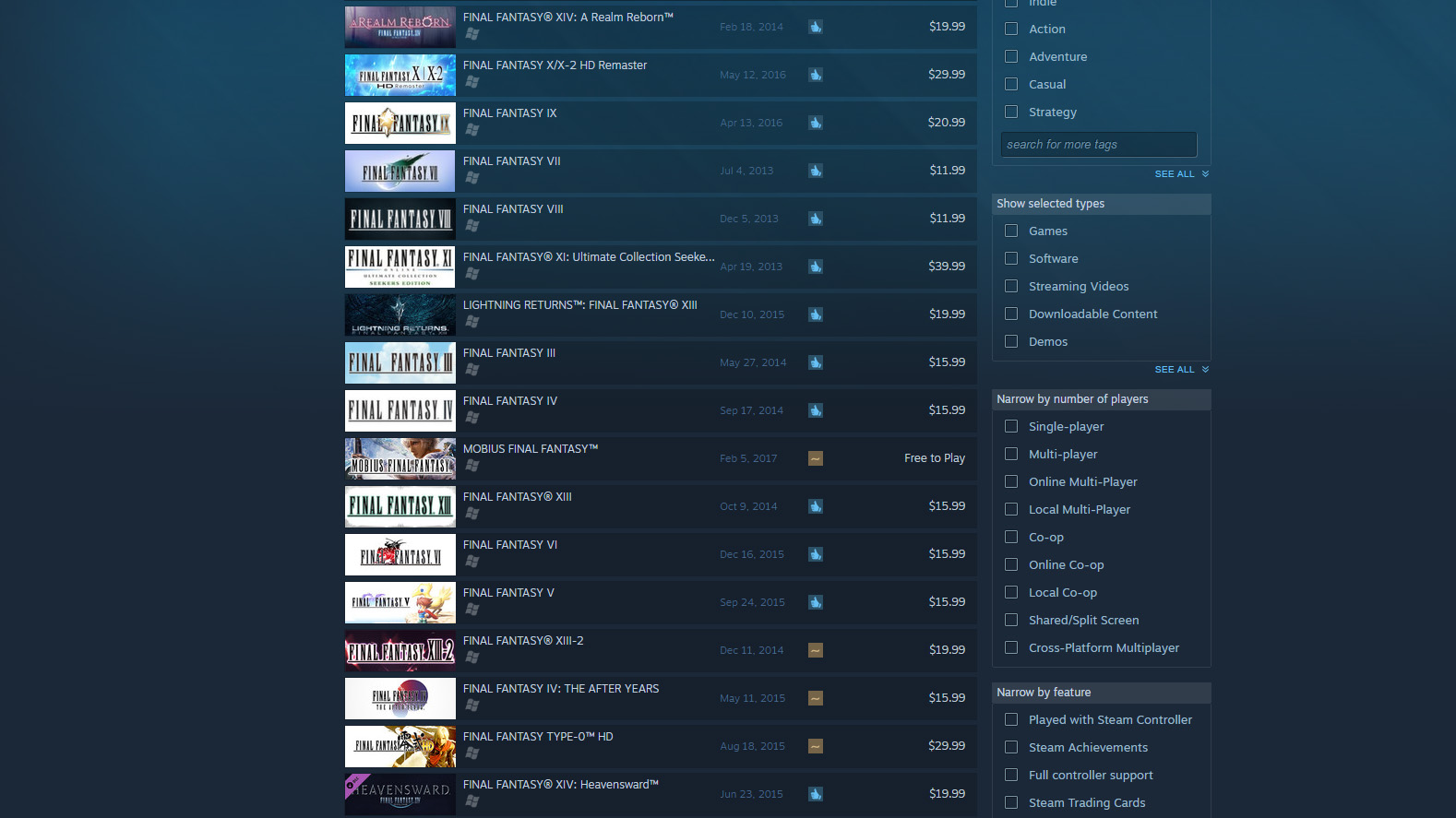

The rise of Japanese games on Steam, 2010 to today

"Recently, as little as 2 or 3 years ago, Japanese publishers and developers alike realized that there is a decent amount of money to be made, certainly Steam being the big place to do that, in the PC space," said DDM agent Ben Judd, who's worked in Japan as a translator and producer for more than 10 years. "So I think a game like Tales does about 500,000 units or so in the PC space, to the point where it's now just another annual piece of the puzzle. Places that didn't actively pursue a PC [version] as many as four or five years ago now totally make that a staple among their console [versions] as well."

If you look at the history of Japanese game releases on Steam, you can see an acceleration not far off from Judd's estimate. The first Japanese game on Steam, as far as I can tell, was Capcom's Devil May Cry 3 in June 2007 (despite its stated May 2006 release on the Steam store). At that point Steam was still young, and only about 100 games were released for the platform in the entire year.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Capcom followed DMC3 with Lost Planet two weeks later. Music puzzler Lumines made its way over to Steam in 2008, and FromSoftware's Ninja Blade and Square Enix's The Last Remnant arrived in 2009. All four were also released for the Xbox 360. Despite being DOA in Japan, Microsoft's console played a key role in making Japanese developers think about the Western audience and Microsoft's other platform: Windows. Those games were trailblazers, but didn't establish a porting trend for any major developers. The modern era of Japanese PC games really began in 2010, with a charming indie sim about running an item shop and a large dump of classic Sega ROMs.

"Recettear was not quite the first Japanese game to get on Steam, but we were the first indie/doujin game to get on Steam and sell really well," said Andrew Dice, who established two-man localization house Carpe Fulgur in 2010. Dice and his partner couldn't find localization jobs and decided to try publishing their own game in the West. After a cold email to the developer of hybrid sim/RPG Recettear, they got a surprisingly positive response and were suddenly in business. "At the time we didn't mention Steam because we had no idea if we'd be able to get on there. There was no Greenlight, no Steam partner program back then. They were approving games individually."

Dice sent multiple emails to Valve with no luck, but he had a plan. Recettear's developers had made a Japanese demo, so Carpe Fulgur localized and released that in English first, hoping it would attract some attention and help convince digital distributors to sell the game. And it worked.

"Apparently a number of people at Valve at the time ended up playing it and were like, 'Hey, why isn't this [on Steam?]' Someone at Valve contacted me and was like, 'Hey, would you like to get your game on Steam?' We were like, 'Sure!'" Simple as that.

I've actually been told that Recettear getting on Steam opened Valve to the idea of putting other offbeat games on Steam.

Andrew Dice, Carpe Fulgur

Dice knew there was an audience on PC for visual novels, which at the time were all fan translated, and for RPGs like Final Fantasy that PC gamers simply had to buy consoles to play. In 2010, Steam had 30 million users and almost no Japanese games. "There was quite a bit of a hole in the market, and one that people wanted filled but no one was really stepping up to try." When he released Recettear in the fall of 2010, Dice hoped to sell 10,000 copies over the course of a year. That would be a success. By the start of 2011, they'd sold 100,000.

"The guys at Valve couldn't quite believe what they were seeing, even," he said. "The fact that it did super duper well, I've actually been told by Western developers, in fact, that they believe Recettear getting on Steam and doing well opened Valve to the idea of putting other offbeat games on Steam. I feel a little self-conscious actually saying that."

Meanwhile, Sega's first wave of classic re-releases on Steam, including Sonic and Golden Axe, were an important connection to an earlier era of Japanese PC releases. The Sega Smash Pack was a poorly emulated collection of ROMs for Windows released in 2000, and like Square's early Final Fantasy 7 and Final Fantasy 8 ports, had long since disappeared from sale outside Ebay.

2011 saw the release of a few more doujin games on Steam, which were small successes. But the Ys RPGs in 2012 were a much bigger hit, proof that small developers could thrive on Steam. Recettear wasn't a one-off oddity. Dark Souls arrived in August 2012 as the last piece of the puzzle: big or small, Japanese games were selling. But that still left the Japanese side of the industry with a big education problem.

"Nobody knew what Steam was five years ago in Japan," said John Ricciardi, co-founder of localization company 8-4, which most recently produced the English version of Nier: Automata. "We’re seeing more and more JP publishers make Steam versions of their games now, but as you know, they still have a ways to go in terms of making them run well from the get-go."

Even as recently as 2015, Steam hadn't quite caught on in Japanese companies. I heard the same thing in an interview at the time with Esteban Salazar, who works as a producer at game developer Marvelous in Tokyo. "The first 20 minutes of any given meeting is explaining what Steam is, the history of the platform, going over the points that Valve makes all the time," Salazar told me at the time. "Variable pricing, the spike in sales, the community engagement, economies in the games, stuff like that. I have to explain it."

But things have, slowly, changed. Salazar pointed out that big companies like Capcom and Sega have led the way in embracing Steam, and like Square Enix, they all have in common a strong, existing Western presence that can talk up how valuable a PC port really is. Aside from Capcom and Sega, it really wasn't until Dark Souls that the other big names in Japan realized what they were missing out on, while smaller developers still needed help understanding the platform. Recettear's developer EasyGameStation had been unusually bold in agreeing to Western distribution; at the time, many smaller developers were content with selling only in Japan.

Nobody knew what Steam was five years ago in Japan.

John Ricciardi, 8-4

Amazingly, Dark Souls was Namco Bandai's first Japanese Steam release in 2012. In 2013, they released Pac-Man Championship Edition DX+, Enslaved: Odyssey to the West and a Naruto fighter. In 2014, Dark Souls 2 arrived a month after the console version and sold nearly a million copies by the end of the year. The PC version represented nearly half of Dark Souls 2's worldwide sales by early 2015.

Dark Souls was obviously a phenomenon, but even ports of older games were outperforming their wildest expectations. The 2014 port of Sega's six-year-old strategy RPG Valkyria Chronicles took the top spot on the Steam sales charts and sold 200,000 copies in just a few weeks—better sales than it had when it was new in 2008. The proper HD port of Resident Evil 4 sold nearly as well. Even more niche games like Dynasty Warriors 8: Xtreme Legends and The Legend of Heroes: Trails in the Sky broke 100,000 sales in 2014.

XSeed, the American branch of Marvelous that publishes the Legend of Heroes and Ys RPGs in the West, was one of the first to tap into the audience for JRPGs on Steam. "I think all development teams in Japan large and small are looking at the PC as a viable gaming platform now, which is quite different from a few years ago when even one of Japan’s longest and most storied PC supporters, Falcom, had to shift over to console as the boxed PC sales market was dwindling," executive VP Ken Berry told me in an interview in 2015. He also offered a partial explanation of why it took years after successes like Dark Souls for more RPGs to show up on Steam: porting older games to PC can be tricky, and until successes like Legend of Heroes: Trails in the Sky and Valkyria Chronicles, it was hard to predict if sales would justify years-long projects for smaller companies.

"The biggest roadblock to porting from one platform to PC would be the availability of the source code (I know it’s hard to fathom how something so valuable could get 'lost,' but it happens a lot more often than one might think), and how compatible that source code is with PC," Berry wrote. "Each project is unique in how many resources are required to complete a PC port, so there’s no magic sales number to target as it’s on a case-by-case basis."

Since Dark Souls' rough landing in 2012, Japanese developers have been going through the growing pains of learning how to support unfamiliar PC hardware. And it's pretty clear that PC gamers care about features and graphics settings. As modder Peter "Durante" Thoman argued in his criticism of the Tales of Symphonia PC port, better quality ports tend to have stronger sales numbers on Steam.

"Some publishers still persist in arbitrarily locking resolution to a 1080p limit, and from time to time we get ports which are not based on the best console version of the games in question," Durante wrote. But in general, he thinks things are looking up, with more day-and-date releases on PC than a few years ago. In his conversations with game developers, he typically gives the same advice he wrote in his 'the features PC gamers want' article, with the added advice to always use the highest quality available assets when starting the PC version. Port developers haven't always followed that best practice.

"PC programming, understanding of architecture, that natural evolution that occurred in the West, never really occurred in Japan," said Judd. "Which is why, if you look at programming skill pound-for-pound, it's much more advanced in the West. We have the background, we have the history, we have the veterans. Japanese people, ever since switching to PlayStation 4 where the architecture very much mirrors PC architecture, now they have to learn that. Most of the people are developing straight on PC, then transferring it to their console of choice, whereas on PlayStation 2, etc., that was not the thing. You developed directly on PlayStation."

But things are slowly changing there, too. Where the first two Tales RPGs were outsourced to PC port houses, the latest, Tales of Berseria, was done internally and released at the same time as the console version in the West. Japanese PC ports are still rarely perfect—modders Durante and Kaldaien have been working on improvements to the image quality in Nier: Automata, for example—but the average is getting better every year.

Today, Japanese developers face the same simple challenge that everyone else does: overcrowding. "The only issue is there's just too much content on any given day, and most independent developers and publishers will say this. It's hard to get user acquisition," said Ben Judd. "It's hard to be seen and heard and understood that your game is out there." Still, fighting for users is better than fighting for the idea of a PC port in the first place.

So that's the how of Japanese PC gaming finally catching onto Steam's massive popularity and gaining a foothold in the West. But what about the why? Why didn't everyone follow Capcom's lead in 2007? Why did it take so long to understand that an audience larger than any single console's would be hungry for games?

There's no single answer, but the basic problem is how few people play PC games in Japan (and how few people own PCs, period). The reasons behind that—the history of Japanese PC games, the differences in indie development, and deeper cultural touchstones—make for some formidable challenges.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).