Our Verdict

A satisfying disassembly sim wrapped in cutting workplace commentary, Hardspace: Shipbreaker is a gig well worth taking up.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? Blue-collar spaceship deconstruction.

Expect to pay: £30/$35

Developer: Blackbird Interactive

Publisher: Focus Entertainment

Reviewed on: Nvidia RTX 2070, 16GB RAM, AMD Ryzen 5 3600

Multiplayer? Online leaderboards

Link: Official Site

My first workplace accident was a doozy. I'd cut my teeth on enough Mackerel-class ships to know 'em like the back of my hand, stripping them bare in seconds. But confidence breeds overconfidence, and in forgetting to decompress the engine room before removing the thruster, I took a 360kg thruster cap to the forehead at 50mph. Flattened my skull like a pancake.

Shipbreaking's good, honest work—but it pays to remember that in space, nobody can hear workplace safety violations.

Two years ago, Blackbird Interactive (developer of Homeworld Remastered Collection and Deserts of Kharak) took a step away from warring empires and operatic battles to focus on a more mundane look at the distant future—a world where those vibrant, Chris Foss-inspired spaceships are just piles of scrap ready to be turned into paychecks.

Cutting edge

Shipbreaker has come a long way since entering early access, but the core shipbreaking has been consistently satisfying since day one. Here's the deal: every morning you begin a shift, picking a new ship to crack or continuing one from the day prior. Each ship is built like, well, a ship—airlocks, engines, reactors and crew compartments layered inside a structural frame and layers of hull panelling to protect them from the elements.

Your first ships are simple enough. Everything can be sorted into three piles—the processor for stuff your employer Lynx wants recycled (usually hull panels), a barge for stuff it wants reused (computers, engines, furniture), and a furnace for scraps it wants rid of. Each piece properly scrapped adds progress towards your work orders, with higher rewards the more efficiently you dispose of a ship. Destroying or misallocating too much salvage will incur penalties, and negligence can even lock you out of the more lucrative rewards.

But as you mop up these stripped-out shuttles, you'll earn commendations with the company, and with it access to bigger, more complex ships to scrap. Very quickly you're forced to deal with pressurised compartments which will explosively, err, 'decompress' if not vented properly. Fuel lines will start fires if accidentally ruptured, mishandled power boxes will set electricity coursing across the ship.

The biggest troublemakers are reactor cores, which require a deft hand and careful planning to remove and put into barge stasis, lest they go supernova and turn your valuable salvage into worthless scrap—and your body into a costly insurance write-off.

Fortunately, earning promotions also gives you more tools to break ships with. Improved grapples and cutters, scanners to check the pressurisation levels before playing with lasers, remote detonators to sever an entire ship's cut-points at once, and tethers that let you pull at objects too heavy for your handheld grapple.

Shipbreaking is a trade, and as you learn the intricacies of each ship class, you start to build little efficiencies and shortcuts. How to place your cutter just right to hit multiple cut points at once, how to use atmospheric decompression to your advantage, the best ways to drag those heavy Atlas engine plates into the processor—and realising you can cut the floor out of a Mackerel to yoink the reactor straight into the barge. It feels like work, sure, but in the most satisfying and rewarding way possible.

In space, nobody can hear workplace safety violations.

Shipbreaker's derelicts are simply a delight to break apart, and there's a real joy to slowly peeling apart what looks at first glance to be a single, solid object until there's nothing left but dust and loose trash. But shipbreaking is hard, dangerous work with extreme risk and low pay—and on its full release, Hardspace: Shipbreaker is a game deeply concerned with what it means to do backbreaking work for a corporation that sees you as (quite literally) disposable labour.

Company time

Cutters start work with two unpleasant benefits: a crippling pile of debt, and the reality that Lynx quite literally owns your body, which is signed-over in your contract and regenerated instantly upon any workplace accident for a modest fee. Every piece of ship you scrap or salvage makes a tiny dent in that debt pile, but the company has a vested interest in keeping its workers indebted. All your tools are rentals, while vital supplies like oxygen, thruster fuel, tethers and repair kits are purchased from the company store (or cheekily scrounged off ships, if you're lucky).

That framing was always there, but Shipbreaker now has a more explicit story that makes clear the developer's stance on worker exploitation. After a few shifts, you're brought into a group call with your fellow breakers—starting with your foreman, Weaver, a man who's here to teach you the ropes as well as act as the intermediary between the cutters and corporate. There's also Kai, the clumsy guy whose stuff is always breaking, while Deedee's the stubborn ol' mother who'll occasionally drunk-dial you after work. And then there's Lou, the dogged optimist who lets you in on plans to unionise Lynx's shipbreakers.

There's plenty of jovial workplace banter, but each and every one of you is struggling under the same weight of debt, and it doesn't half feel like you're all basically imprisoned by this job.

The company is your family, even as you pay a premium for your own death.

Some of this chatter plays out during shifts, but much of it happens in your Hab—a 3D dorm where you can upgrade equipment, check your mail and plan your next shift. It's a messy, utilitarian space, but one you can make a little cosier by snatching posters and plushies from the ships you break. Weaver will even give you his old busted-up shuttle as a gift, and you can sneak in a few components during shifts to fix it up after work.

Emails will fill you in on game progress with the occasional side of corporate propaganda, but private newsgroups let you know how the union plans to deal with, say, an administrator coming down from corporate to crack down on activists. Lynx is just another Amazon or Tesla, and Blackbird is deft at writing the kind of slimy, family-friendly language these corporations use to dissuade unionisation efforts.

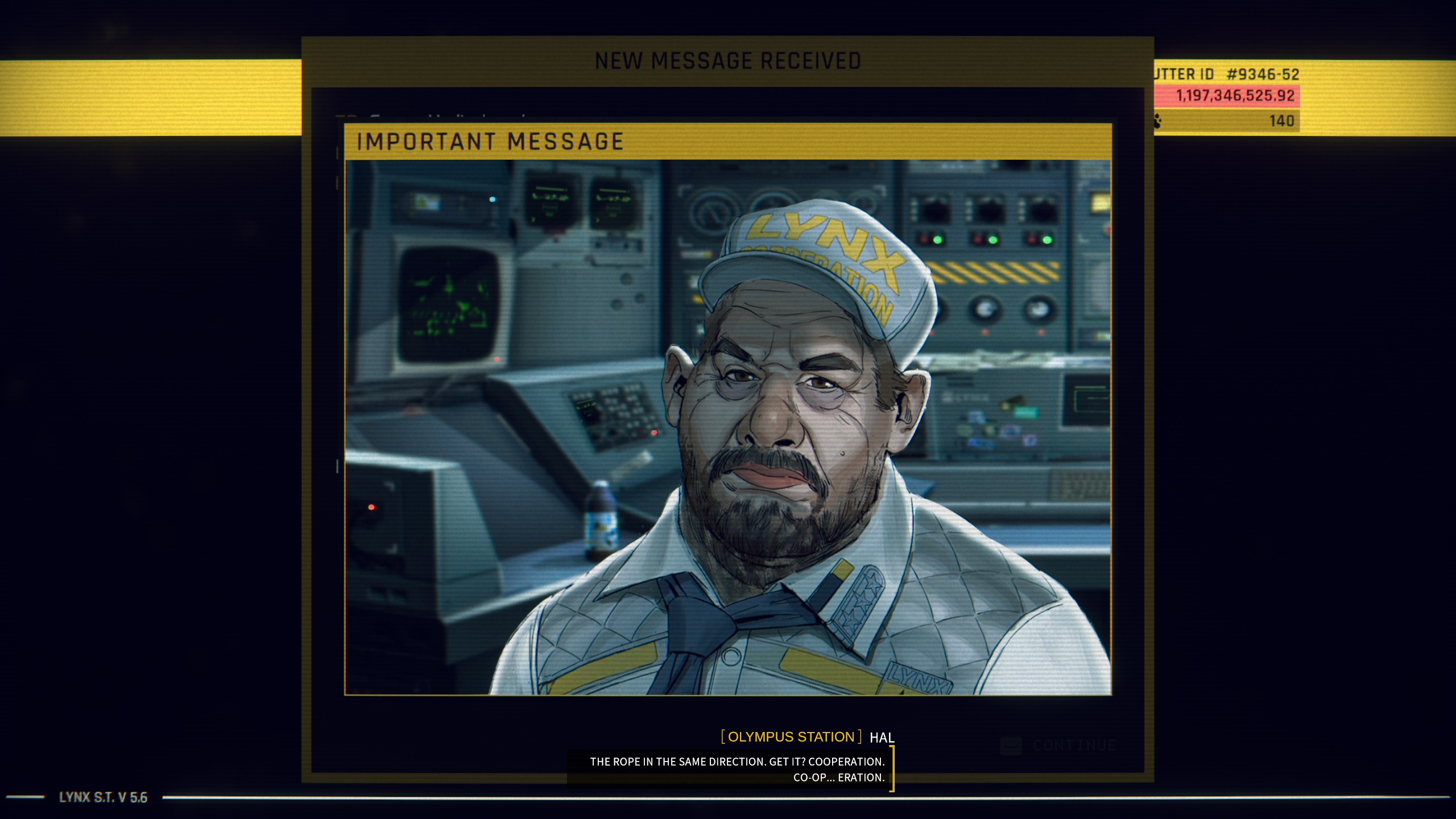

Your man from HQ isn't a suit, he's another worker just like you—touting the values of following proper procedure and the importance of "pulling the rope in the same direction". The CEO sends uplifting videos about how the company is your family, even as you pay a premium for your own death.

Shipbreaking is good, honest work, and Hardspace doesn't think there's anything wrong with a bit of manual labour. It's a game that relishes in teaching you the joys of learning a trade, even if it's a ridiculously far-flung trade like cracking open starships. When I strip a Javelin to the bone in two straight shifts, I feel an immense amount of satisfaction in my ability.

Simultaneously, however, it makes it clear that multinational (multiplanetary) corporations and the pursuit of growth at all costs robs workers of their dignity and agency, turning jobs into effectively indentured servitude. It's a voice that elevates Hardspace into more than just a wonderfully tactile zero-g demolition sim.

It's a game about being proud of a job well done, and fighting to make your workplace one you can be proud of. It's a deliberately repetitive thing, which might be tedious if you can't find enjoyment out of methodically cutting apart ships across two, three, even four continuous shifts. Where small ships broke apart in minutes, pulling apart a Javelin or Gecko requires real commitment.

It's not a job for everyone, but it's a job well worth trying. And hey, if you manage to avoid accidentally shooting too many fuel tanks with your laser cutter, you might even manage to float away debt-free someday.

A satisfying disassembly sim wrapped in cutting workplace commentary, Hardspace: Shipbreaker is a gig well worth taking up.

20 years ago, Nat played Jet Set Radio Future for the first time, and she's not stopped thinking about games since. Joining PC Gamer in 2020, she comes from three years of freelance reporting at Rock Paper Shotgun, Waypoint, VG247 and more. Embedded in the European indie scene and a part-time game developer herself, Nat is always looking for a new curiosity to scream about—whether it's the next best indie darling, or simply someone modding a Scotmid into Black Mesa. She also unofficially appears in Apex Legends under the pseudonym Horizon.