Greek Squad: Scientists continue troubleshooting 2,000-year-old computer

Longest IT job ever—but after a century of research, there's been a breakthrough in modeling the first known computer.

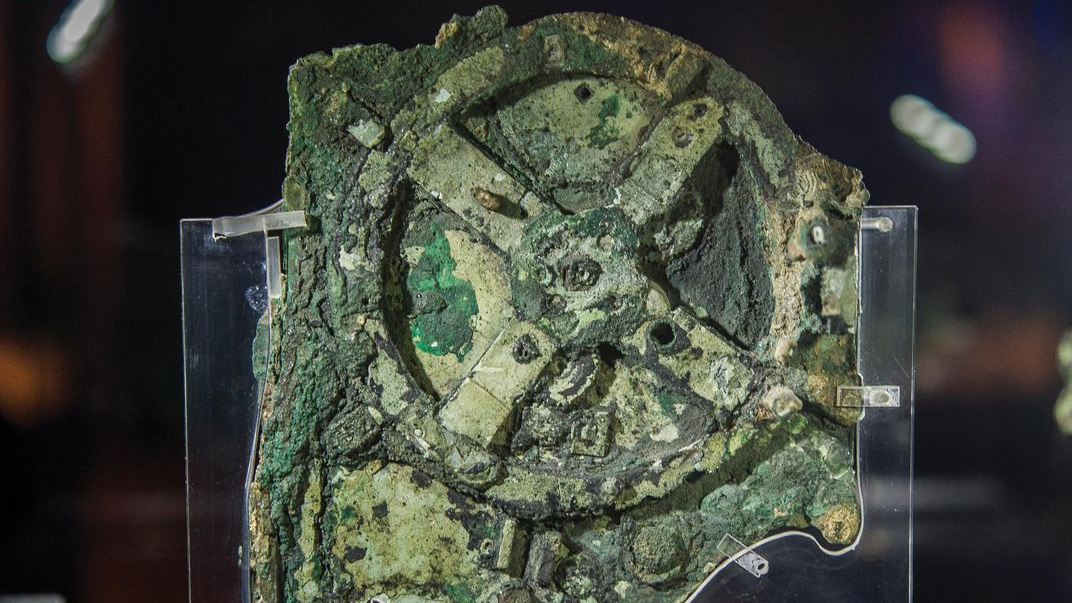

If Archimedes had a laptop, would he ever have gotten around to calculating pi? If he'd been born 2,500 years later, I can imagine him minimizing Minesweeper to pull up a Google doc of equations every time the teacher walked by. Dude would've loved sudoku. A century after Archimedes, circa 100 BC, the ancient Greeks actually did have small computers, though they weren't yet good at distracting from the task at hand. They were analog computers like the Antikythera mechanism, built for specific calculation. The Antikythera mechanism may well be the first computer ever made, and despite more than 100 years of study since it was uncovered in a shipwreck in 1901, scholars are still trying to figure out exactly how it worked. It probably hasn't helped that the remains look about as crusty as a CPU cooler that hasn't been cleaned since Quake was new.

The Antikythera mechanism is thought to be an ancient Greek astronomical calculator, meant to show the movements of the planets using a very complex series of interlocking gears. Unlike the early digital computers of the 20th century, it was also remarkably compact, at around a foot tall.

It took decades of study to figure out what the Antikythera mechanism was and what it did, because few of the pieces survive. But no model has actually been able to match a theoretical mechanical design with the actual known movements of the planets. At least, until now.

Somehow, from the badly corroded remains of the computer, researchers have been able to come up with what they believe is an accurate working model of the Antikythera mechanism in its original form, by matching the inscriptions on the front of the device that specified how it was meant to work far more closely than any previous effort.

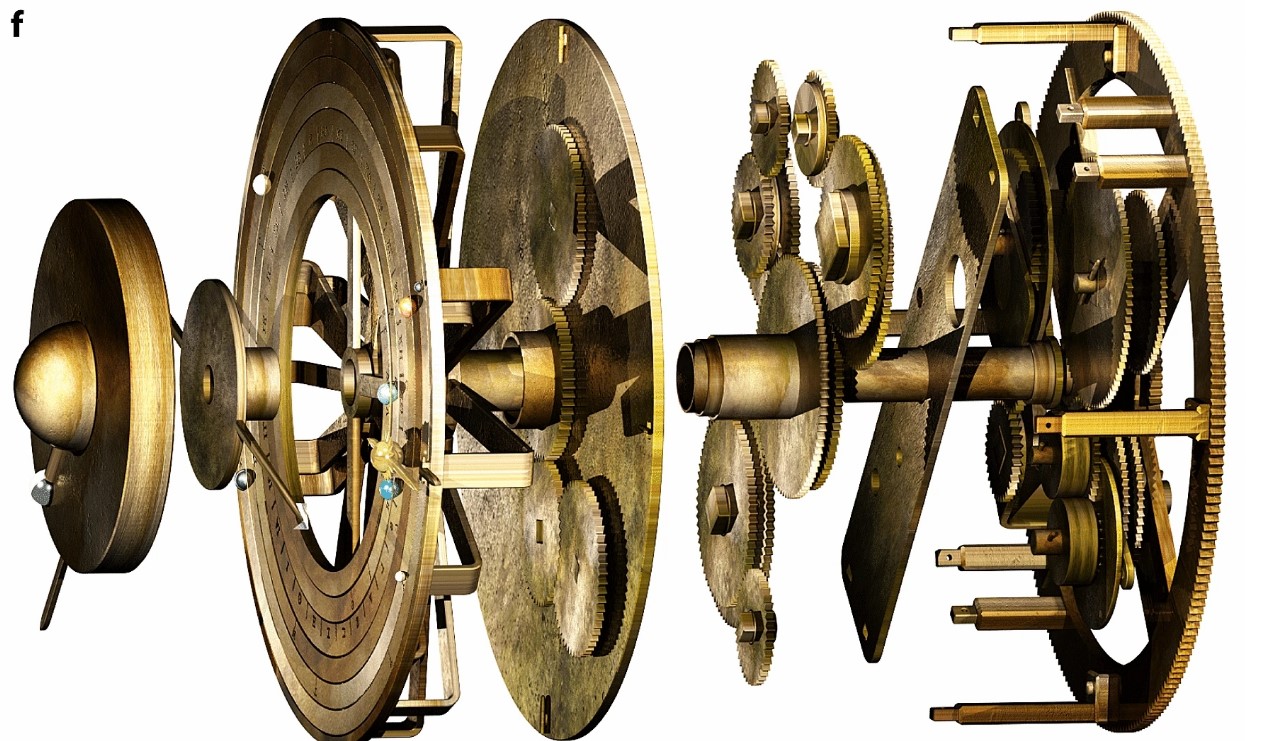

"Inscriptions specifying complex planetary periods forced new thinking on the mechanization of this Cosmos, but no previous reconstruction has come close to matching the data," says the research paper published today in Scientific Reports. "Our discoveries lead to a new model, satisfying and explaining the evidence. Solving this complex 3D puzzle reveals a creation of genius—combining cycles from Babylonian astronomy, mathematics from Plato’s Academy and ancient Greek astronomical theories."

As The Guardian breaks down, the researchers at University College London are building a recreation of the Antikythera mechanism with today's machinery, and if it works, they'll see if it's possible to recreate with the technology of the Greeks circa 100 BC. The design looks dizzyingly complex even today, with rings for Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the Sun and Moon, and could calculate all of this, according to the report:

- The ecliptic longitudes of the Moon, Sun3 and planets

- The phase of the Moon

- The Age of the Moon

- The synodic phases of the planets

- The excluded days of the Metonic Calendar

- Eclipses: Possibilities, times, characteristics, years and seasons

- The heliacal risings and settings of prominent stars and constellations

- The Olympiad cycle

How big a deal was this circa 100 BC? The report says that the Antikythera mechanism is an astronomical compendium of "staggering ambition," and that it represents "the first steps to the mechanization of mathematics and science." It ends by casually tossing out that the computer "challenges all our preconceptions about the technological capabilities of the ancient Greeks."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

That is, however, a sticking point in the researchers' new model of how the device may have been put together. They used a set of nesting tubes to fit more than 30 interlocking gears and the arms representing the planets into a tight 25mm space. Doable today—but could the Greeks have actually built it? One of the researchers, Adam Wojcik, told The Guardian, "The concentric tubes at the core of the planetarium are where my faith in Greek tech falters, and where the model might also falter… Lathes would be the way today, but we can’t assume they had those for metal."

Still, if the design bears out, it may be a breakthrough 120 years in the making. I'd like a replica for my desk, please.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).