Our Verdict

A brilliant climbing adventure that siphons the rage out of navigation puzzlers like Death Stranding and Baby Steps, resulting in something prickly, but warmly approachable.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A limb-by-limb climbing sim that reaches dizzying heights

Release date January 30, 2026

Expect to pay TBC

Developer The Game Bakers

Publisher The Game Bakers

Reviewed on RTX 3060 (laptop), Ryzen 5 5600H, 16GB RAM

Steam Deck Verified

Link Steam

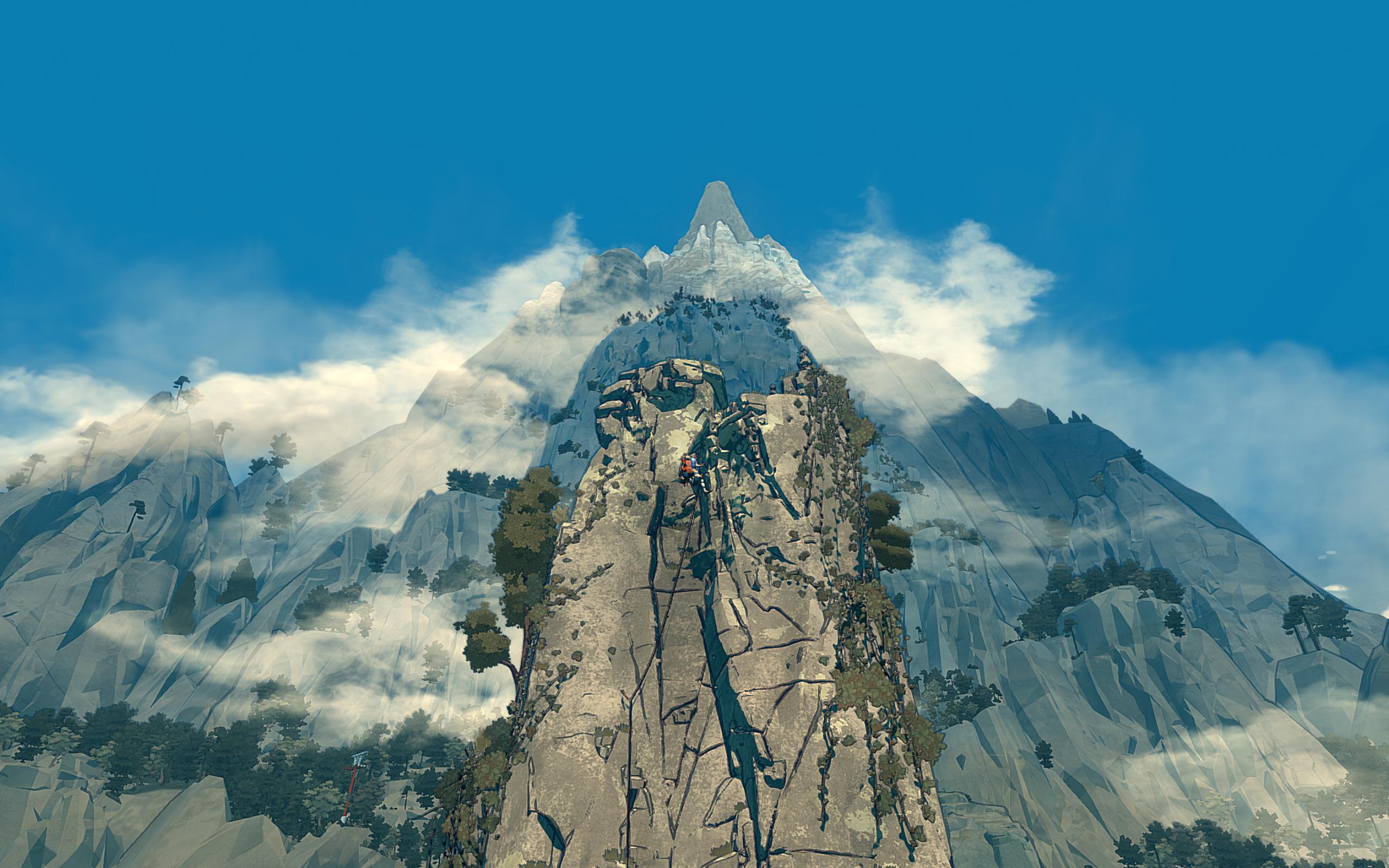

Cairn can be loosely categorised with modern on-foot navigation games like Death Stranding and Baby Steps, but once it clicks, it's more fun to play than either of those. Protagonist Aava is a renown mountain climber with a formidable reputation and reclusive spirit. We meet her at the foot of Mount Kami: an impossibly lofty summit once home to a society of troglodytes with a preference for living vertically. It's her self-assigned mission to be the first to surmount it. What follows is a 15 hour odyssey, or a potentially endless one, about the excruciatingly careful placement of hands and feet on vertical surfaces. It feels grander in scope than anything I've played in recent memory, and it's among the best videogames I've played in years.

The climbing feels unrefined at first, because I've never climbed like this in a game before. Moving one of Aava's limbs is as simple as pressing A, moving it with the analog stick, and then tapping A again for her to affix that limb to the surface. The game automatically selects which limb will move next according to whichever is bearing the most weight, and this can feel counterintuitive at first, near unmanageable, but the logic clicks well before the title card appears. It's possible to choose limbs manually, but this functionality is hidden in the gameplay menu: it's basically nightmare mode and newcomers should avoid it.

Most sensible routes along the rock faces have pockmarks or narrow shelves, but naturally they're rarely placed exactly where you need them, which feeds into a diegetic stamina system communicated by Aava's increasingly shaking limbs, the severity of her breathing, the blurring of the screen, and—if you have a controller with rumble—the vibrations in your hand. Sometimes there's no avoiding a risky scramble, but you'll need to pull it off quickly. It's possible to rest a loadbearing limb with a button press in order to briefly stabilise Aava, but if it takes too long to find a position that equally distributes her weight, she will fall.

Not always to her death, though: Aava has pitons she can plunge into the cliff faces, and these serve as temporary safe zones or checkpoints (but not save points) during lengthy ascents. Once a piton is applied she can go "off belay"—a state of safe hanging—in order to replenish her strength and access her backpack. These pitons are limited and I usually only had three or four at my disposal, so it's important to place them smartly because it's possible to lose a lot of progress in this often unforgiving game. When I'm on stable ground I can command my generations-old robot pet to retrieve my pitons, but not always intact: sometimes they break.

Crag out

Once the risk-reward rhythm of this process sinks in, the climbing in Cairn takes on a slowburn fluency. With only a couple of silly exceptions I think I took the path of least resistance up Mount Kami, but the further up the mountain I charted the more obvious it became that there's a dizzying amount of options. Make no mistake, though: taking the harder and more expedient routes, and not the safest ones, won't feel wise on a first playthrough, because Aava also needs to eat, drink and sleep.

Aava is not an avatar, she's a fearful, enigmatic character. But her mystery inevitably sheds as her sense of mortality grows

These survival systems feel cruelly onerous at first, and if you want, you can turn them off. Aava sets off at the foot of Mount Kami with little in the way of supplies: she is at the complete mercy of the mountain. She can only properly rest and thus save at pre-determined camp sites, and long stretches of vertical wayfaring can pass without any source of water or foragable pots.

I don't think you should toggle the survival systems off, though. As punishing as it sounds, The Game Bakers have tightly designed this realism so that most players will feel the odds insurmountably stacked against them before relief arrives at the eleventh hour. That was my experience at least, as a player taking the loosely signposted paths. There were points where I felt like my run could easily be doomed, before I reached an intermediary summit with a camp site, a pond full of fish, or a gaping cave full of milk-swollen goats. The relief is immense.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

I think it's probably possible to reach dead ends in Cairn, where you're too far from resources, and thus too exhausted, to make the next climb to a campsite feasible. The possibility of having to go back several save points ratchets the tension.

These survival aspects may be a bridge too far for some players, but they're a crucial element in the unusually subtle emotional stakes that accrue throughout Aava's odyssey. Because this is not strictly a game about finding footholes in an inhospitable mountain: this is a game about the limits of a body. Cairn doesn't romanticise the bravery and determination of Aava to climb this majestic, static adversary. If anything it takes pity on her, but from a dignified remove. It's quickly established that she's brilliant, but she's not a hero.

Enough rope

When Aava falls she often scolds the mountain and herself. Sometimes she screams at it. She doesn't quip: she rages in a guttural way that stings. Her hands become torn and bloodied, and I have to patch them up manually, finger-by-finger, with bandages.

When Aava finds a camp, and when she sleeps to replenish her health, she doesn't even sleep the whole time: she starts doing push-ups and sit-ups, or else she reads a book. She has a self-flagellating mind of her own.

When I meet another climber on this famously deadly trek, I'm prompted to fob the boastful upstart off. I'm more inclined to be polite—as gratingly earnest as this character is—but Aava is so lost in her solitary project that chance encounters on the remote summits of impossible mountains often register as an annoyance. Aava is not an avatar, she's a fearful, enigmatic character. But her mystery inevitably sheds as her sense of mortality grows.

This is a game of strange encounters, in the same way Baby Steps was, but if Baby Steps was absurdist Cairn is quietly surreal

There is a backstory of sorts for Aava, and an unfolding mythology attached to Mount Kami itself, but the narrative stakes in Cairn are entirely to do with the fallibility of the protagonist's muscles, flesh, and bodily demands, and her determination that these natural limitations should prove no obstacle. It's difficult to substantiate in words how connected I became to Aava's animal strengths and constraints, more so than her psychology, but that's the magic at the heart of Cairn: it conveys physicality in a tactile medium best suited to dramatising it. Cairn knows it's uniquely qualified to execute on its concerns. Its sharpest qualities—the fear it captures, the vertigo it conveys, the risk it constantly demands, the gratification it stingily doles out—could not be adequately captured by more passive mediums.

It's also cinematic and featureful, in a way that gratifies every seemingly impossible climb. I climbed not to have climbed, but to see what lay beyond the next shelf (Aava might disagree). There's always something. This is a game of strange encounters, in the same way Baby Steps was, but if Baby Steps was absurdist Cairn is quietly surreal: It's dreamlike because its gentle, almost drowsy meditative qualities can morph into nightmare fuel on the flip of a dime.

Storytelling in games is so often saccharine and pushy, or else tiresomely verbose, or obscure in an over-compensating way. Cairn leans into its unforgiving systems, rather than its writing, to substantiate Aava. And for the gentle stroke of their brush, The Game Bakers has created a protagonist ruthlessly human in a landscape that won't catch her when she falls.

There are some blemishes. Aava's relationship to flat surfaces can be vague at times, and sometimes I resorted to using photo mode, rather than the purpose-built wayfinding view, to chart a rough path up the mountain. It can be buggy, albeit rarely: during one of the climactic summits, I landed on a surface large enough for Aavi to stand on, which tricked the game into thinking I had reached the summit, thus skipping the last stretch of a treacherous climb.

As critical a problem as that last bug is, it didn't undermine my enjoyment of Cairn. I haven't even talked about the quiet pleasures of cooking, or the capriciousness of the weather and how it can screw you over, often forcing you to hang and wait while Aava thirsts and hungers. Relatedly: climbing at night sucks. And I haven't mentioned how gorgeous Cairn's rugged but readable art style is, and how often I deployed the photo mode.

Comparisons to Death Stranding, Baby Steps, Peaks of Yore—even QWOP—feel suitable even though this is a tonally different beast. On paper it reads as a more grounded and earnest approach to this burgeoning orthodoxy, and maybe that's exactly what it is, but it's the surest sign yet that this still-marginal style of game—let's call it body drama—is ripe for further development and exploration. Cairn feels like a landmark, in the sense that it's the first of its kind that I'd unreservedly recommend to everyone.

A brilliant climbing adventure that siphons the rage out of navigation puzzlers like Death Stranding and Baby Steps, resulting in something prickly, but warmly approachable.

Shaun Prescott is the Australian editor of PC Gamer. With over ten years experience covering the games industry, his work has appeared on GamesRadar+, TechRadar, The Guardian, PLAY Magazine, the Sydney Morning Herald, and more. Specific interests include indie games, obscure Metroidvanias, speedrunning, experimental games and FPSs. He thinks Lulu by Metallica and Lou Reed is an all-time classic that will receive its due critical reappraisal one day.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.