RPGs may never top Ultima 7, but Divinity: Original Sin 2 comes close

Ultima 7 bears a heavy crown as the king of computer RPGs. Original Sin 2 proves Larian may have what it takes to usurp the throne.

For more of Richard Cobbett's inisght into the Ultima series, check out this feature on the Legacy of the Avatar.

It’s no secret that from the start, the Divinity series has had its sights set on respectfully dethroning Ultima 7. "Everything out there after Ultima 7 never did it as good as Ultima 7," Larian founder Swen Vincke once said. It's for RPGs what The Secret Of Monkey Island is to adventures, what Doom is to shooters, and what Shakespeare is to English literature, and not just because it's the last time a game was able to get away with 'thou', 'doth' and the rest of ye olde English without the world justifiably taking yonder piss with a catheter.

It hasn't been an easy road. The first Divinity game suffered from trying to do Ultima 7 without the lessons of first making Ultima 1-6. The passion was there, but the time wasn't right. Similarly, later games soon set a trend of having phenomenal ideas—psychic powers, turning into a dragon, being soul-bonded with a death knight and so on—but without the budget or RPG foundations to really make them sing.

With Divinity: Original Sin though, Larian finally pulled it off, gambling everything on a game that nearly bankrupted them. The multiplayer-first design meant that every system had to be rock-solid, Kickstarter offered both the money and the need to build a reasonable framework, and in those limits, the company's passion and talent finally found the home that it deserved. Fast-forward, and Divinity: Original Sin 2 is even better, tightening up the storytelling, greatly improving the characters and questing, and still overflowing with ideas and humour, without being quite as goofy as its predecessor, and offering a less convoluted but far stronger plot.

In short, I absolutely love Divinity: Original Sin 2. It's one of my favourite RPGs in years, and when I put that in the context of having not liked the original Divine Divinity much at all, that's only to reinforce how glad I am that Larian kept pushing forwards, kept the faith, kept evolving, and finally created a sequel that unquestionably carries the spirit of Ultima while still having its own very different, distinct soul. On any terms, it's an absolute triumph.

But speaking as an old-school RPG fan, how goes its quest to beat it? Is it finally time to stop bringing up the 90s classic in every conversation and move on?

A legend returns

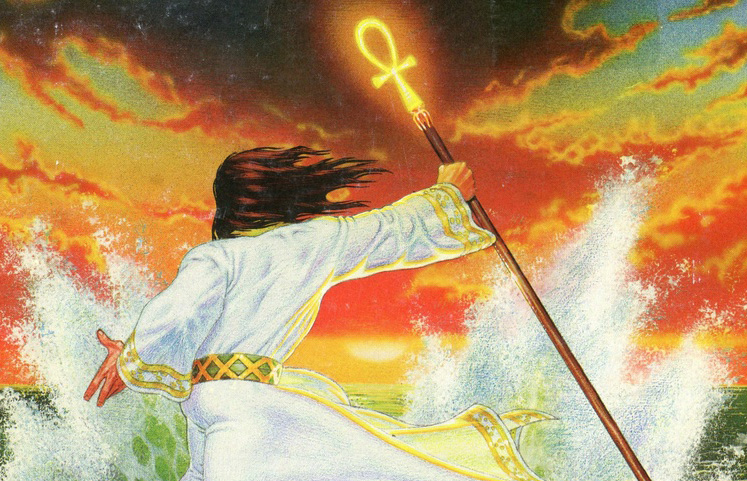

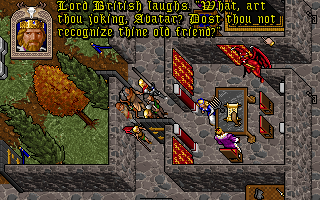

I know it's an unfair comparison, because it’s not really Ultima 7 the Divinity series is going up against, but the legend of Ultima 7—the Platonic ideal of the open world RPG that was established back in 1992. I was thirteen when I not simply played it but got blown away by it. That huge open world. That freedom. The fact that you could bake bread and eat it. It was both a design and technical milestone in an era where 256 colours were still a novelty. The villain could talk to you. In real speech! You could blow up the world with Armageddon!

It’s not really Ultima 7 the Divinity series is going up against, but the legend of Ultima 7—the Platonic ideal of the open world RPG that was established back in 1992.

Never mind that games like Minecraft have long since surpassed its scripted, largely sign-posted crafting, or that the combat was dreadful, or that the world isn’t actually THAT big if you take a step back. No game will never supplant my love of Ultima 7 because no matter how much tech or how much brilliance you put it in it, it will never fill my soul with the magic that those chunky VGA sprites and a few speech files did back then. The same goes for many longtime RPG players, who hold Ultima 7 in high esteem - perhaps even Vincke himself. And no, you'll never experience that same feeling now, if you play Ultima 7 in a world with the likes of Planescape: Torment and Skyrim and Dragon Age. You missed it. Sorry.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

At the same time, Ultima 7 doesn’t just cast a shadow. In being that illusion of a perfect RPG, even if in practice it’s far from it, it offers a great guiding light for Divinity as a whole—highlighting both how far it’s come, and where the issues still are. Again, it’s come a hell of a long way. As much as I hate to say it, Divinity: Original Sin 2… deep breath… is a better game than Ultima 7 in pretty much every way, from the depth of its world simulation to its raw mechanics and combat and character building. Certainly, as a standalone adventure.

But what more might it be? What else has Ultima 7 to teach?

Pathfinder

Let’s start with the world. By far the worst part of both D:OS and D:OS 2’s design is that they pretend to be an open world, but they’re not. In practice, there’s a strict path that you’re meant to follow around the world. Trouble is, it’s unmarked, usually makes little logical sense, and is managed by the fact that enemies with even a slight level distance on you are notably more powerful and will typically squish you flat.

To use Reaper’s Coast as an example, you start on a main road leading north, with a town off to the west. Despite the map pushing you onwards and upwards, exploring that way only going to lead to your death. The design actually wants you to go into down and poke around there. While less problematic than some of D:OS’ pathing, this fights against both your natural inclination to explore, and often the drive of your character’s own quest at that, and the fact that the goal of the map is open in a similar way as Baldur’s Gate 2’s second chapter—to hook up with Sourcerers and learn from them, in essentially isolated modules that feel like you should have more freedom than you do.

Let’s compare to Ultima 7. One of the big lies of Ultima 7 is that it’s an open world game. This is true to a point, in that you can go almost anywhere, but in practice the intended journey around it is linear (this is why when you die, you return to the same place to be told where the people you’re chasing have gone next, to put you back on the correct course). The map itself is then typically controlled not by beef-gate monsters and impossible fights but environmental hazards like poison swamps and locations it’s pretty clear you’re not equipped for. It’s a far more naturalistic approach than just throwing in some assassins or similar to block the way, especially when the scenery itself can convey the hint that you’re getting out of your depth.

Whether Divinity wants to convey the feel of an open world or not, this is something that needs improving next game. This doesn’t mean dragging the player around by the ears or cutting out exploration, just better guidance. More clearly name checking the next camp they have to go to. Having extra NPCs and encounters point them in the right direction, and making the map progression feel like encountering natural resistance instead of punishment for not reading the map designer’s mind. The guards in Reaper’s Coast who warn you away from one of the local evil Sourcerers are a great example of D:OS2 addr—you’re welcome to ignore them and head off into a spooky part of the map anyway, but it’s on your own head.

The old school vs. the new order

When you’ve got as many characters and subquests as a modern narrative game, a notepad doesn’t necessarily cut it.

On a similar level, and this isn’t unique to Divinity by any stretch, D:OS2 features a lot of old school moments where the designer’s intent simply isn’t clear and intuition doesn’t cut it. Many older fans chafe at modern niceties like flags on maps and being led through every step of a quest, and that’s fine. The catch is that you can’t simply remove them without having something to take their place, especially with a map and suite of skills as big as D:OS2’s. I remember not being able to find a location I ‘knew’ was on a creepy island because I was failing a stat check, despite it being on my main character’s critical path. Later, almost at the end of the game, being Mr. Clever about one puzzle solution involving a judgemental statue meant never even speaking to the character who was meant to tell me how to get past a later puzzle. Cue a vast amount of frustration and resorting to Google.

Now, Ultima 7 offered no in-game quest log at all. True. It was the era where you were expected to have a notebook on standby. However, it was good at directing players to the next location, and its puzzles and situations weren’t typically that complicated when you arrived. For all the baking bread talk and world simulation going on, dungeons tended to be about basic stuff like pressure plates and dragging things onto things versus pen-and-paper style adventure modules.

When you’ve got as many characters and subquests as a modern narrative game, a notepad doesn’t necessarily cut it. Modern narrative driven RPGs offer far more tools and possibilities than the Avatar and friends had, and that player feedback is important. It’s not a question of dumbing down, but designing so that the player can better intuit what the designer wants. After all, in real life if someone asked you to deliver a package, you could at least outright say “OK. Where to, exactly?"

What we fight for

Most of this is of course implementation rather than design philosophy per se, and again, D:OS2 is a massive jump over its predecessor. The same applies to the story. It’s a wonderfully simple concept where all your party members are competing to become the next Divine, against a background of wider political and metaphysical messing around. It’s a fantastic RPG story because it’s simple enough to grasp and appreciate the implications of, wide enough to allow more or less any smaller story within its confines, and feels both epic and personal. It’s not as complex as, say, Planescape Torment, but it works in a similar way.

The Ultima games from Ultima 4 onwards were overtly About Something in a way that very few RPGs manage to be.

So why does Ultima 7 still feel like it has an edge? A couple of reasons. The first is that its world of Britannia is a place that doesn’t simply have lore, but history. You’ve visited it as the same character, and adventured with the same Companions, and seen the same towns many times over. It’s like a virtual home away from home, kept interesting by the constant changes to the status quo in each game—in Ultima 7, the biggest being that you’ve been gone for 200 years and life has moved on without you. You see it as you explore, both in the stories you hear and the quests you complete, and in the incidental details as people go to work, go to bed, head to the local tavern, and otherwise show off all kinds of NPC scheduling fun that’s all the more incredible for how hard that stuff is for games even twenty-five years later.

That sense of life would of course be wonderful to see in Divinity. However, even excluding it and focusing on the sense of Home that Ultima 7 offered, it’s not hard to see how the series has squandered its potential somewhat and doesn’t have the same foundation. The big reason is that despite all the games being set in the world of Rivellon and having a few recurring characters, each game time-jumps and focuses on completely different areas each time. They’re connected by lore, yes, but that’s not the same visceral sense of returning to a beloved world that you get in long running series like, say, Tex Murphy’s Chandler Avenue and Monkey Island’s corner of the Caribbean, nor are there many familiar characters there to greet you and feel like old friends who are glad to see you back.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with this approach per se, but it does mean that the familiar tends to be mechanical, like the Pet Pal perk, or mythological like its pantheon of gods, versus recurring characters to deal with on a more human level, like Bracchus Rex, Damien and of course Lucian the Divine.

The second is that while their success has arguably been overly glorified over the years, the Ultima games from U4 onwards were overtly About Something in a way that very few RPGs manage to be. Ultima 4 of course was about becoming a hero, Ultima 5 about the misapplication of justice, Ultima 6 about racism and tolerance, Ultima 7 about corruption and the power of religion, and Ultima 8 about a hero forced into a position of doing evil for the sake of the greater good.

(We don’t talk about Ultima 9).

Specifically, Ultima 7 features persuasive moral philosophy and shows how it can be perverted to promote selfishness and obedience to a cause, the much denied but blatant fact that the villains are a pastiche of Scientology, and smaller stories involving many important themes of the time such as drugs and the growing violence of the media, as seen by the fact that your first encounter is a bloody sacrificial murder site full of assorted giblets.

This isn’t to call out Divinity: Original Sin 2 for not following the same storytelling path. Both its main story and its character based plotlines are excellent. It is however a big part of Ultima’s core design philosophy—that RPGs can be about more than gods and monsters and saving the world. Though nothing else has truly surpassed it, bits of that have wormed their way into many RPGs since, to make them more than the sum of their adventures. Planescape has ‘What can change the nature of a man?’, while Fallout followed both its catchphrase ‘War never changes’ and the unspoken ‘even as the world does’ in developing its world.

These are the touches that help a story really resonate; to sink their claws in and stick with you as meaningful long after the credits rolled. That resonance is also a big reason why other classic RPGs like Might and Magic and Gold Box games may be beloved by fans, but the likes of Ultima and Wasteland remain nothing short of legendary decades after their time.

A legacy within reach

The Divinity series isn’t quite at that level yet. But as I said at the start, that’s not intended as a criticism—talking in these terms, and about that possibility, is intended as a huge compliment. Nothing has ever gotten closer to beating Ultima 7 at its own game, and that includes its sequels. To accomplish that and still have time for ideas as great as Pet Pal, talking to ghosts, and a campaign that works just as well if you play it straight or if you team up with friends and murder everyone Diablo-style is nothing short of incredible.

The fact that there’s still inspiration to be taken from the classics is honestly exciting, especially after seeing the love and commitment in every part of the jump between D:OS and D:OS2. Maybe the next Divinity: Original Sin will finally push over the edge, or maybe the company will go in a different direction entirely—to take the vast amount learned so far and create something that’s entirely their own, as, say, Troika did with Vampire: Bloodlines, Toby Fox did with Undertale and BioWare did with, ooh, let’s say 2.9 Mass Effects.

But that’s for tomorrow. For now, let’s stick with what really matters. Whether Ultima 7 can ever officially be ‘beaten’ or not, nobody has come half as close as Divinity: Original Sin 2. It’s a great RPG on its own terms. It does the greatest RPG of all time proud. Most of all though, it should give RPG fans everywhere reason to be excited about the future of both the Divinity series, and the as-yet unknown promise of anything else Larian might have bubbling away over in its labs. Anyone else’s fingers crossed for urban fantasy?