Looking back on Myst, and the aftermath of its unbridled success

What’s the downside of creating a flip-book puzzle adventure game that makes you a legend of early-90s video game design?

Way back in deep geological time (aka, 1973) a musician named Mike Oldfield created a prog-rock album called Tubular Bells. It was one of those rare pieces of art that was both revolutionary and inoffensive, such that, as far as can be determined, every single person who owned a record player in the 1970s bought a copy.

Oldfield became a household name and an icon of British music, despite never quite revisiting the high of his first album. Sure, he had success, but everything he did after 1973 has been defined as either “trying to be Tubular Bells again” or “deliberately trying to NOT be Tubular Bells again.”

Which brings us to Cyan.

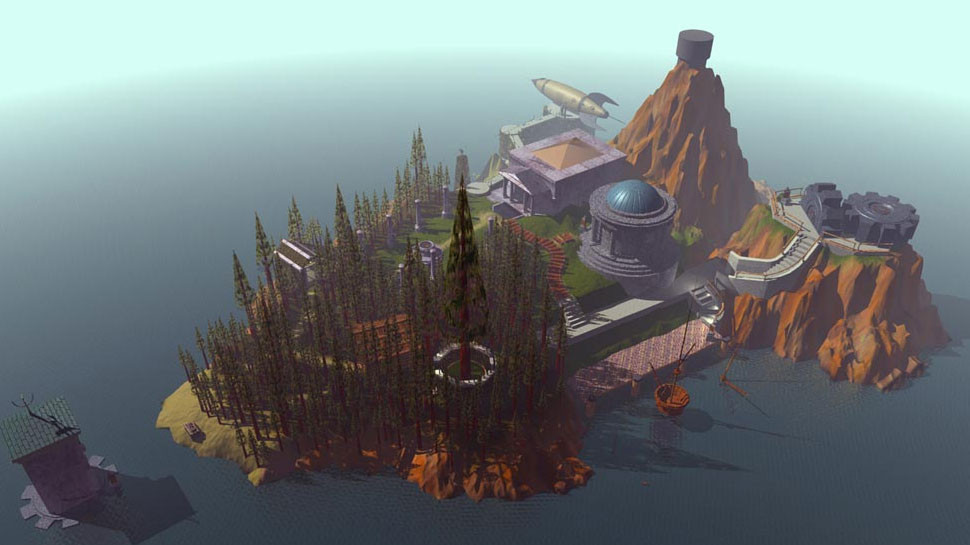

A tidy 20 years after Tubular Bells, and in a completely different medium (although one in which Oldfield himself lusted for relevance, at least for a while), brothers Robyn and Rand Miller used Apple’s Hypercard programming system and a whole lot of Silicon Graphics rendering time to create Myst.

When Myst hit shelves in 1993, with its postcard-like still-image environments, between which the player would move with no animation whatsoever, PC gamers were already anticipating a real-time future. We had the 7th Guest, which used pre-rendered animations to move from puzzle-room to puzzle-room. We had Doom, of course, which hinted at a hyperkinetic future of extreme energy and violence. And we had an existing pantheon of great games, from Wing Commander to Police Quest and more, that promised us the future of gaming was to be cinematic, not literary.

Myst, on the other hand, ran on the Mac. Because of this, it penetrated what was, in the 1990s, a vast and untapped market: non-gamers. Everyone bought Myst. My dentist bought Myst. For years, probably until at least 2000, whenever you tried to tell a non-gamer (especially a Mac user) about some amazing new graphical innovation on the PC, they’d say: “Sure, but did you ever play Myst? Now those were good graphics!”

Back in the 1990s, non-gamers failed to understand something very basic. Graphics are supposed to move. Merely using a Silicon Graphics workstation to ray-trace a fantastical and surreal island landscape with, like, an airship and cogs sticking out of the ground, wasn’t enough. PC gamers demanded worlds, not storybooks.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

PC gamers demanded worlds, not storybooks.

To be fair to the Miller brothers, Myst never pretended to be anything other than literary. Its “linking book” mechanic made that explicit. The whole point of the game was to move around a weird island and engage with weird puzzles. Its mindset was all about the detail. The graphics had to be in 640x480 so you could see if the tiny pilot-light on the boiler was actually lit or not.

And the machines of 1993 absolutely could not render at 640x480 real time. Oh fine, maybe Microsoft Flight Sim 4.0 or something, but not a fully-textured environment with thousands of polygons. Also the Millers couldn’t really, you know, code.

Myst came with a Journal in the box, all official-like and bound and nice. When you opened it, the book was blank. You were supposed to keep notes in there. Sketch constellations. Make maps. Myst bombarded the player with esoterica and made no attempt to hold any hands.

It also had no timer, no countdown, no score, no lives, no levels, nothing that non-gamers usually associated with games. Because in 1993, the wider population thought of games as being fancier versions of Space Invaders, or maybe Super Mario “Bross” if they were particularly hip.

Myst offered the proto-humans of the 1990s the experience of staring at a screen for five minutes, clicking a lever, going “Hmn…”, and then shutting down the PC to go and make dinner. It was, in many ways, a preview of the future.

Myst was duly ported to pretty much every platform that existed at the time including the Atari Jaguar, sold six million copies, and remained the best-selling PC game until the Sims came along in 2002.

Meanwhile, Cyan went on to produce a sequel called Riven.

Riven sold 1.5 million copies in 1997-1998, was critically lauded, and is still probably under-appreciated, at least in terms of how much raw human talent went into its creation.

But after Riven, the Miller brothers parted creative ways. Cyan (the company) built a super-cool HQ in Washington State, with just the most awesome sunken creative library-type central area, and spent the next decade trying to build a real-time, massively-multiplayer version of Myst, called Uru.

Uru had a very troubled life, occasionally popping up on live servers only to be shut down shortly thereafter by whichever publisher had been mad enough to take it on that year.

Ubisoft somehow got mixed up in the whole thing, and while waiting for Cyan to do something—anything—tasked other studios with creating Myst III and Myst IV. These were perfectly adequate Myst-clones that sold unspectacularly. Meanwhile, Uru gathered itself a tiny cult following and refused to either take off or completely die.

That didn’t keep the lights on at Cyan, of course, so the developer found itself more or less compelled to create Myst V: End of Ages. Because this was 2005, Myst V was a real-time game but Cyan’s decision to texture-map live actors onto 3D character models produced ghastly results. If nothing else, Myst V proved that the pre-rendered, flip-book style of Myst and Riven had been a super-correct decision on Cyan’s part.

Uru trundled along in the background and its fate is complicated and only really interesting to people who love Uru, and those people already know the story. Its servers were even hosted by fans at one point. Cyan released a couple of expansions for it, and it’s on Steam again. For some reason.

Which brings us back to the Mike Oldfield comparison. Oldfield fanatics will know our Mike has a habit of starting every single new album with a haunting piano or synth lead that, even if only ephemerally, evokes the famous opening to Tubular Bells (you know the riff if you’re a fan of the Exorcist).

So too has Cyan sort of devolved into a company that repackages Myst onto every possible platform to extract every possible dollar from this 25-year-old game. Peak cynicism was achieved in 2000, when Cyan created realMyst, a realtime version of, uh, Myst. And then realMyst Masterpiece Edition 2.0 in 2015, which had higher-resolution textures.

Despite every Cyan game being on Steam in a package that crashes a lot, a Kickstarter pulled in $2.8M for yet another repackage of every single Myst-branded in one, easy-to-pay-for download, with physical rewards for the highest tier backers.

What does any of this mean? Probably something about being aware of early success. And something about how Cyan should let this venerable property fade into memory with grace, like Chris Roberts has done with Wing Commander. Oh wait...