Google Stadia has game developers confused, excited, and worried

"We're reaching uncharted territory."

Cloud gaming is the future of gaming, at least if you ask every major tech company. From Nvidia to Sony and even Walmart, tech giants are racing to build the Netflix of games, and Google's Stadia has the potential to be the one that changes the industry forever. But not everyone was psyched about Google's big reveal.

Speaking with several game developers before, during, and after GDC, where Google unveiled Stadia to the world, they all shared common concerns: What will the revenue models and contracts look like? Who owns the game data stored in the cloud? Who is cloud gaming really for?

"We're reaching uncharted territory that could have lasting implications for creator's control over their content," said Chris Dwyer, an independent games consultant. "Streaming in general represents the most platform control over actual game content we've ever seen."

Google's presentation did little to stem Dwyer’s concerns. The technology Google demonstrated has been around for a while—essentially, games are rendered on remote servers and streamed to players as video, while their input is sent back—so the announcement's focus on Stadia's technical aspects (and no information on how Stadia works on a business level) left devs to speculate on what it means for them—and the future of the games industry as a whole.

Revenue models and contracts

Cloud gaming was already here before Google’s announcement, so there are precedents we can look to. And especially for indie developers, some of them are worrisome.

Gaming services currently pay developers in two different ways: traditional revenue share and pay-per-hour (or pay-per-play, which isn’t that common at the moment). The traditional model is what we're used to: stores like Steam sell individual games and take a cut of the revenue. Stadia and other streaming services can still work like that, but they might instead offer a subscription like Netflix or Spotify.

"We could see a swing towards a 'pay-per-play' business model, where either time spent or number of sessions is the metric used to determine revenue share." said Mode 7 Games joint managing director Paul Kilduff-Taylor. "This will greatly favour games with high retention, and potentially shut out things like short narrative experiences even further."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

If a pay-per-hour model does become common, another concern is that future games could have hours of "bloat" in them just to increase the playtime, and thus the developer's revenue. It happened with YouTube (which, remember, Google owns). Its recommendation algorithm favored longer videos, and so videos started getting longer. The same thing happening to games is entirely possible.

How can someone who is making a game right now know how well their game is going to do a few years down the road?

As of now, though, there aren’t many streaming platforms that pay by number of hours played, Utomik being one of the few. Google hasn't announced its plan, and may opt to sell games individually. But to some devs, that lack of clarity is concerning.

"If these big platforms over the course of the next 12 months announce they're taking subscription models ... developers need to understand that," said Mike Rose, founder of No More Robots. "There are people who are making games right now who need to be warned."

In other words, how can someone who is making a game right now know how well their game is going to do a few years down the road, assuming Stadia actually does take off? Developers don’t have metrics or data yet for this kind of thing, and don't know anything about how revenue will be shared.

According to Rose, subscription platforms currently claim that having your game on their service doesn't eat into sales numbers—it just adds more players rather than replacing normal game sales. But Rose is convinced that will change as subscription models become more popular and people buy fewer and fewer games.

“It's going to happen," he said, "we just don't know when."

Developing games for a cloud streaming future

Right now, Google is pitching cloud gaming as an improvement over local rendering in technical ways, both for players who get high-end graphics on low-end machines, and for developers. For the latter, the company is creating its own cloud-based development platform.

Currently, game developers are limited by game engines that run on monolithic architecture, like Unreal, and by games that have to run on lots of hardware. Features are cut or scaled back. Physics simulation gets more modest. Many things are downscaled, especially in big-budget titles.

According to Google, the company's cloud-based dev tools will solve those problems by transitioning to distributed architecture inside games for the first time. “Rather than doing the physics over and over again for each player, you do it centrally and distribute it out, [through the cloud]," said Google lead designer Erin Hoffman-John during a panel at GDC.

Developers could do this for any or all parts of their game, which would mean the ability to create games on whatever scale they want. In theory, cloud-based games wouldn't be held back at all—there's practically no upper limit on the potential computing power.

But all this is designed for developers making big budget games, not indies who want to create more intimate experiences. "Not every developer has the skills or inclination to create huge systemic games, or titles with many hours of content," wrote Paul Kilduff-Taylor in an email.

Assuming that these dev tools are meant to make games for Stadia, that brings up more questions: how difficult would it be for developers to port their game to PC, if they can at all? If game developers use Google's cloud tools to create their games, would Google require them to store their games on its cloud?

Without clear answers from Google, these questions don’t matter much in the short term. But if Stadia takes off, cloud-based dev tools might be the only option for developers to create their games in the future, or at least the most convenient one. It could also mean that cloud gaming technology will outpace desktop PC hardware technology, and gamers won’t be able to run some games on their machines, only in the cloud.

Again, while the technology has interesting implications, Google has left developers with a heap of unanswered questions. And there are just as many for us as players.

Who is game streaming for?

We don't know yet how Stadia will be priced. Some services, like Shadow and Nvidia (although it’s still in beta, there were talks of charging by the hour at one point), charge a monthly fee and require the user to own a copy of the game. For those who have older hardware, spending ten bucks a month might be preferable to spending hundreds on a new PC, though it's a hard sell for existing PC gamers.

But what about those who have unreliable or virtually nonexistent access to the internet? The gaming community had this same conversation when Microsoft announced that the Xbox required an always-on internet connection—something it later walked back because of the negative reception.

About 24 million Americans do not have access to high-speed internet.

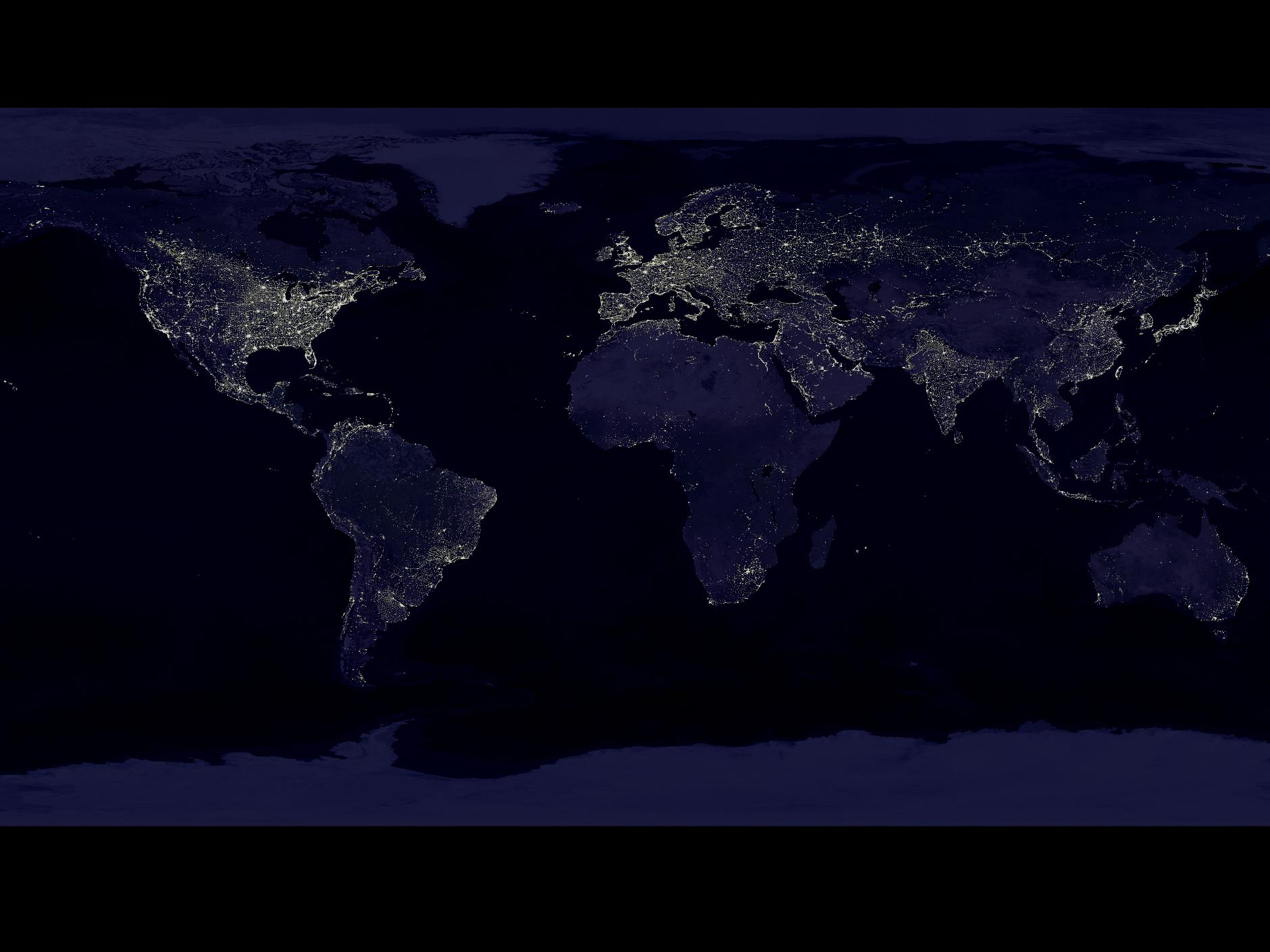

This was one of the many issues brought up at an IDGA sponsored roundtable at GDC. How can Stadia—or any game streaming platform—make gaming for everyone if not everyone has an internet connection, or a reliable one? "You’re pushing out a community that may want to have access to this," one developer at the roundtable said. If cloud gaming becomes the main way we play games at some point in the future, but not everyone has constant access to high-speed internet (which they won't), then it very much limits the diversity of gamers.

About 24 million Americans do not have access to high-speed internet, according to Motherboard. Furthermore, a December 26, 2018 FCC report revealed that the median download speed in the United States was 72Mbps. (The FCC also defines the minimum download speed for online multiplayer games at 4Mbps. Seriously.) Globally, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) estimates that 3.9 billion people, or 51.2 percent of the world’s population, have access to the internet, but that number doesn’t indicate how many have access to high-speed internet.

Stadia and other cloud gaming services can make gaming more accessible on the hardware side of things, but if you don't have high-speed internet, fugetaboutit. A future where cloud gaming is the norm limits how far games can reach, and there's no solution for that right now.

Privacy

Another major concern among developers and players is privacy. Who will own the gameplay data Stadia collects, and what will Google do with it? Many at the IGDA roundtable thought Google would probably own it, but others argued that things don't work that way with other platforms. For instance, Amazon AWS clients don't give Amazon ownership of their customer data, per their agreement, but it's anyone's guess as to what Google will do. "We'll have to see what their contract says," said an attendee.

"You aren't thinking nearly paranoid enough about this," said another, noting that Google is a data mining and machine learning company. "They can learn things about you that you might not know about yourself by analyzing gameplay data."

Another speaker added that Google is an advertising company, too, and suggested that our gameplay recordings could be used to sell us things. Will the future of gaming be as dystopian as the current state of YouTube's ad placements? Will I get an add for diapers or skin ointment in the middle of an emotionally intense cutscene? I can't even have a face-to-face conversation with someone about a product without seeing an ad for it later on Facebook. No joke.

Check back in a few years

The advent of game streaming and subscription services doesn't necessarily mean the death of PC gaming as we know it, even if Stadia ends up being as successful as Google hopes. Mode 7's Kilduff-Taylor brings it home with an optimistic thought: "There will always be an attraction to having a powerful computer in your own home running software that you control and store locally. Just as we've seen a resurgence of physical media in music, and limited edition physical game releases, I don't expect this to ever fully die out."

Even so, developers aren't dismissing the possibility of a streaming future. Look at how many tech giants want a piece of cloud gaming: Google, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, EA, Nvidia, PlayStation, and more. These companies wouldn't be pushing their streaming services—way before any of them have really figured out how to deal with latency—unless they believed there was money to be made. And with so few answers right now, it's no surprise developers are concerned it'll be at their expense.

Google has left us all with questions. The best we can do as members of various gaming communities is protect our spaces until we're satisfied with the answers we get—if we ever can be. For developers, it's clear the next few years are going to be filled with uncertainty as Google and other companies push hard to make cloud gaming the norm. As for me? I'll stick with my desktop PC.