Our Verdict

The R9 Nano is the fastest GPU ever crammed into Mini-ITX motherboard dimensions, but youll pay extra for the small size.

PC Gamer's got your back

(+) Condensed Milk: Compact; quiet; tiny; efficient; did we say small?

(-) Sour Milk: Expensive; not as fast as larger GPUs; 4GB VRAM; niche.

Meet the AMD R9 Nano: World’s Tiniest High-End GPU

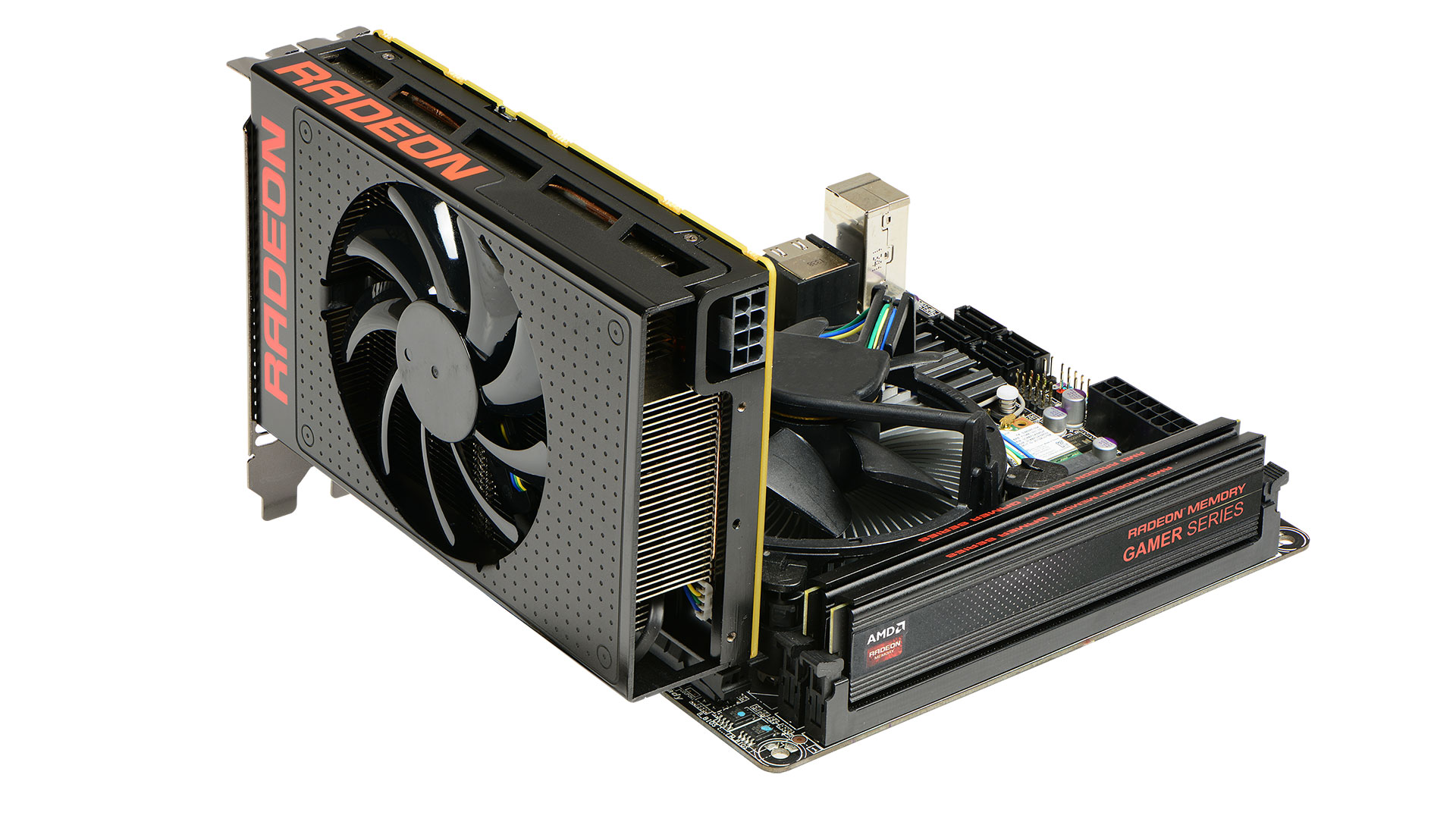

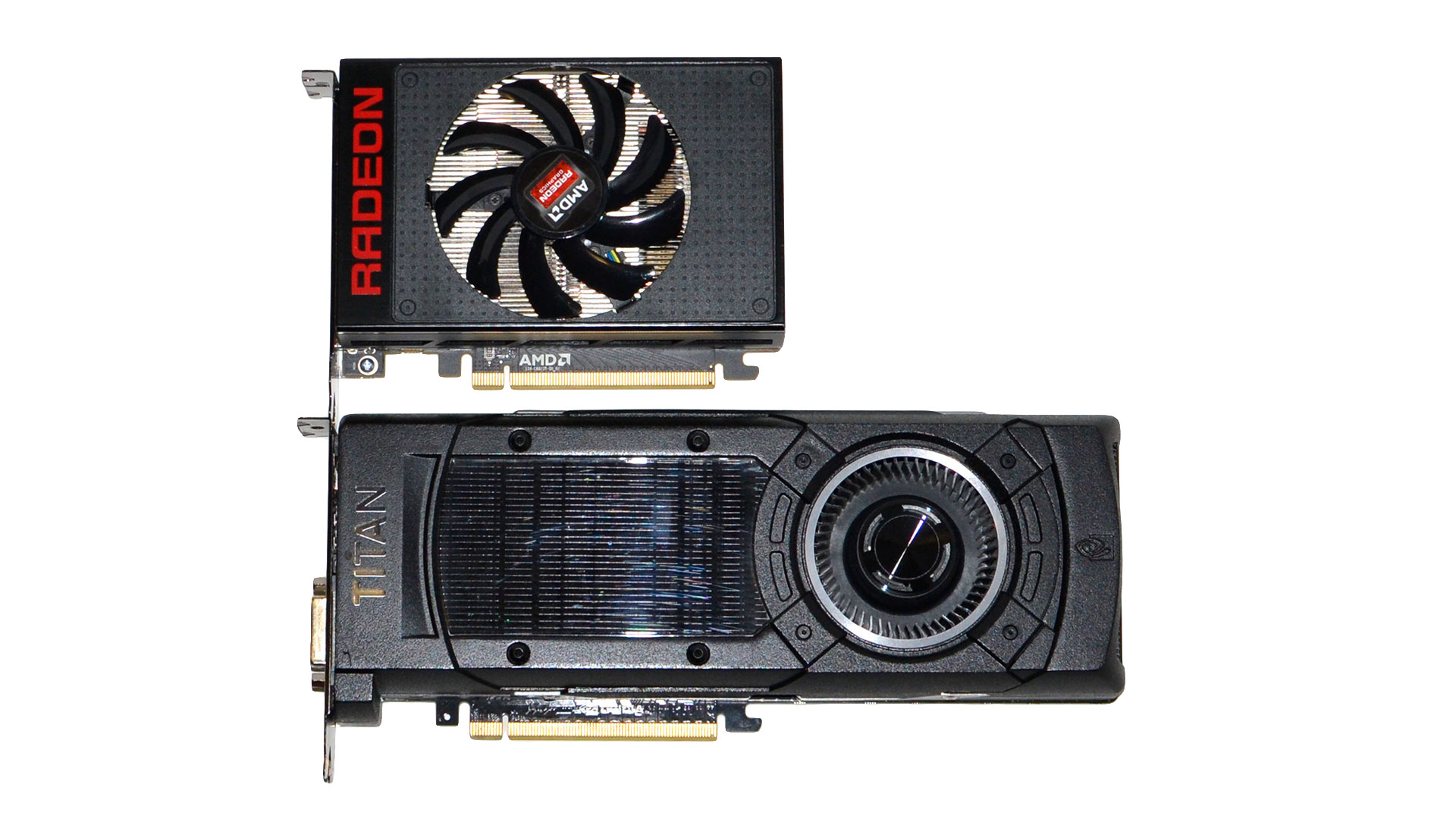

If the name didn’t give it away, and you haven’t been paying much attention to AMD’s marketing for the past month, let’s just get this out of the way: the AMD Radeon R9 Nano is positively tiny! Caveat: for a really powerful GPU, and we’re mostly talking about the length. The R9 Nano is still a two-slot GPU, and it’s not a half-height card by any stretch of the imagination, but it is about as short as you can make a graphics card while still providing for the full x16 PCIe connection.

When you first see the Nano, you’ll be duly impressed: It’s only six inches long, making it 0.6 inches shorter than the closest contender (Asus’ DirectCU Mini GTX 970). When you pick it up, it’s still somewhat heavy, checking in at 0.61kg—the Asus GTX 970 Mini weighs a similar 0.64kg, but a stock Zotac GTX 970 (the lightest high-end GPU in our labs) only weighs 0.51kg. By comparison, a full-size GTX 980 Ti tips the scales at 0.91kg, and Fury X (including the CLC) weighs 1.51 kg, though half of that is in the CLC. Regardless of how you slice it, we’re still looking at a healthy reduction in overall size and weight.

We’ve covered the specs for Nano already, but here’s a recap:

| AMD High-End GPU Specs | ||||

| Card | R9 Fury X | R9 Nano | R9 Fury | R9 390X |

| GPU | Fiji | Fiji | Fiji | Hawaii (Grenada) |

| GCN / DX Version | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Lithography | 28nm | 28nm | 28nm | 28nm |

| Transistor Count (Billions) | 8.9 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 6.2 |

| Compute Units | 64 | 64 | 56 | 44 |

| Shaders | 4,096 | 4,096 | 3,584 | 2,816 |

| Texture Units | 256 | 256 | 224 | 176 |

| ROPs | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| Core Clock (MHz) | 1,050 | Up to 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,050 |

| Memory Capacity | 4GB | 4GB | 4GB | 8GB |

| Memory Clock (MHz) | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,500 |

| Bus Width (bits) | 4,096 | 4,096 | 4,096 | 512 |

| Memory Bandwidth (GB/s) | 512 | 512 | 512 | 384 |

| TDP (Watts) | 275 | 175 | 275 | 275 |

| Price | $649 | $649 | $549 | $429 |

The long and short of it is that Nano is the same core hardware as the Fury X, but binned for power and not necessarily pure speed. That means limitation of Fury X like the 4GB HBM are still present. The graphics card is also designed with lower power draw as a major objective, and it sports a single 8-pin PEG connector providing it with a maximum in-spec power draw of 225W. The 175W TDP is much lower than that, which means there should be a decent amount of overclocking potential. But most people are going to want to know how the Nano performs at stock, and how far it may end up dropping below its maximum 1,000MHz core clock; in our testing, it generally stays above 900MHz in most games, with occasional drops into the 850MHz range.

One of the big differences between AMD and Nvidia is how they report GPU clock speeds. AMD reports a maximum turbo clock, and outside of exceptional workloads (e.g., Furmark), their GPUs should generally run at the stated turbo clock. Nvidia in contrast has an advertised base clock, which is the minimum clock speed the GPU should run at, again outside of exceptional workloads. However, Nvidia also has a Boost Clock that’s a better representation of the expected minimum clock speed, and in systems with decent airflow their GPUs will almost always run at higher clocks than the advertised Boost Clock. Basically, Nvidia likes their GPU owners to feel like they’re getting more than they paid for rather than coming up short.

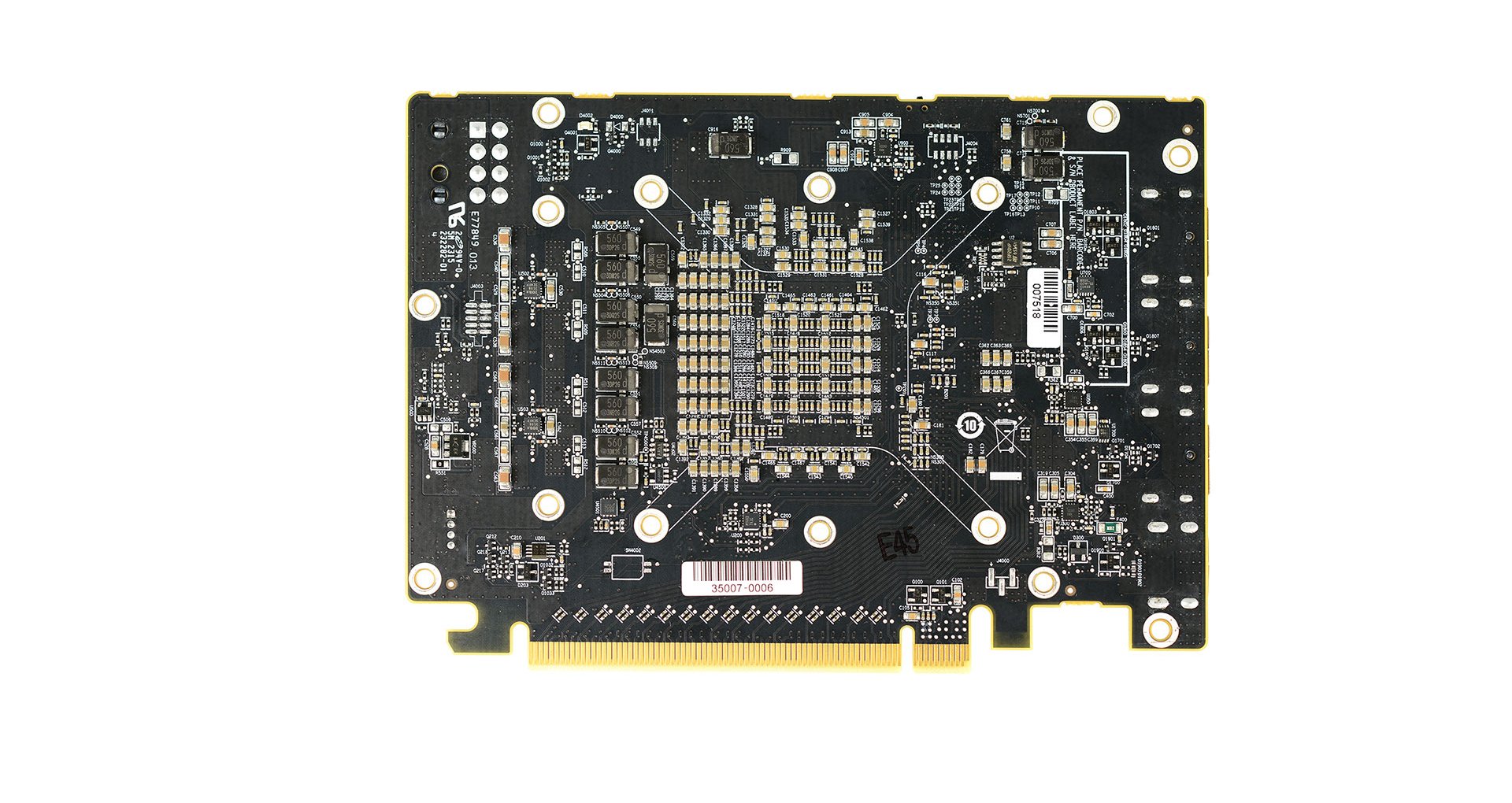

Pictures are worth a thousand words, so the above gallery just saved us a lot of typing. You can see the various promotional images AMD provided for the R9 Nano above, along with some of our own shots comparing the Nano to the standard GeForce reference blower and some other GPUs. You’ll notice AMD puts a strong emphasis on the Mini-ITX aspects. Yes, the R9 Nano lives up to its name and is smaller than all of our other high-end GPUs. It’s also faster than many of the larger GPUs despite its diminutive size, but we’re jumping ahead. If you’re interested in building a gaming PC with the highest performance per volume, a Mini-ITX system with R9 Nano makes for a perfect match.

This raises a simple question: if you’re not interested in building a small rig, is there any reason to consider the R9 Nano over the identically priced Fury X? The answer isn’t quite so simple. The short answer is no, there’s not. The longer answer is that R9 Nano should be offered in non-reference cards in the coming months. It’s possible that some of those will actually be larger cards with air cooling rather than a CLC, but overclocked to perform the same as Fury X. Even if they’re still small cards with R9 Nano clocks, there might be a few use cases where having multiple Nano cards is better than trying to fit multiple Fury X CLCs into a case. Regardless, use cases outside of small systems are going to be pretty niche.

It's not all sunshine and roses in Mini-ITX land for the R9 Nano either. For HTPC use, R9 Nano lacks HDMI 2.0 support, something that will become increasingly important over the coming years. Many Mini-ITX cases also exist that have no trouble accommodating a larger 10-inch graphics card, and in fact the number of cases that are large enough for the Nano but not large enough for a GTX 980 Ti is quite limited. Now add in the need for a Mini-ITX PSU with an 8-pin PEG connector and at least a 400W output. Nano effectively targets a niche within a niche, but we still think it's awesome, and we're hopeful that others will run with the idea and create some new designs that were previously deemed impractical.

How Fast Is the R9 Nano?

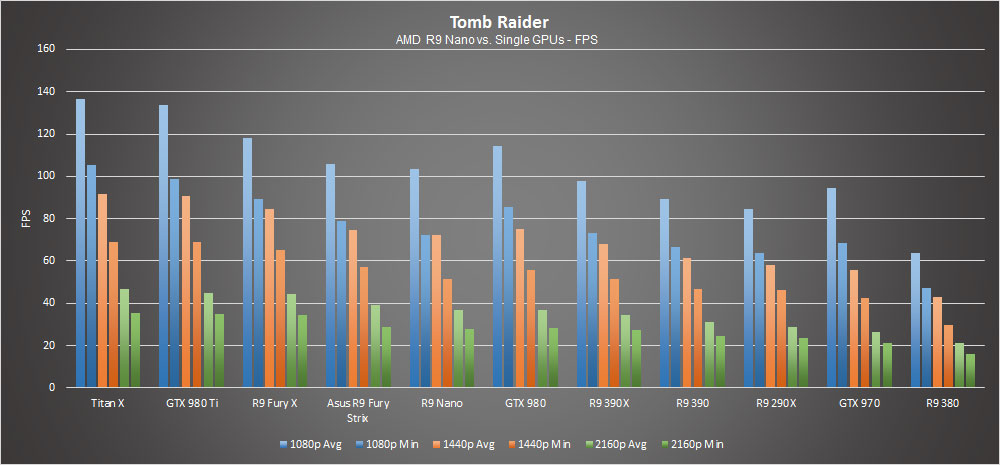

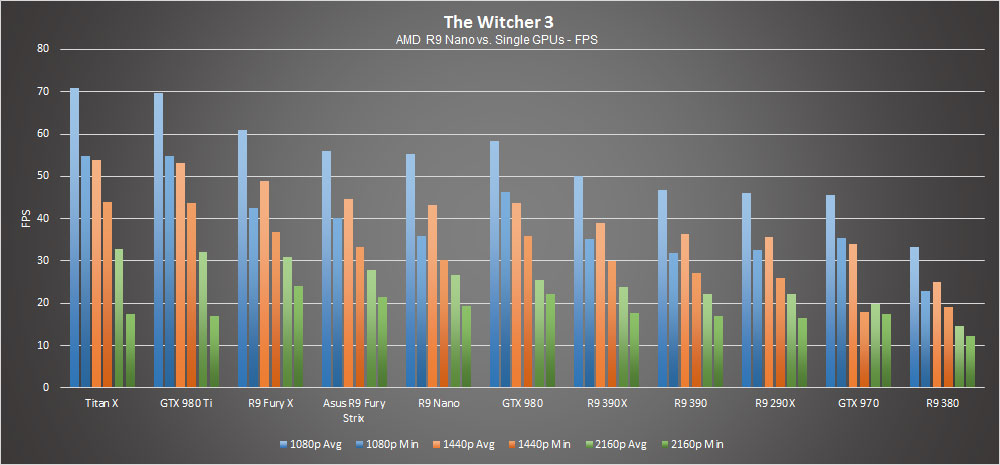

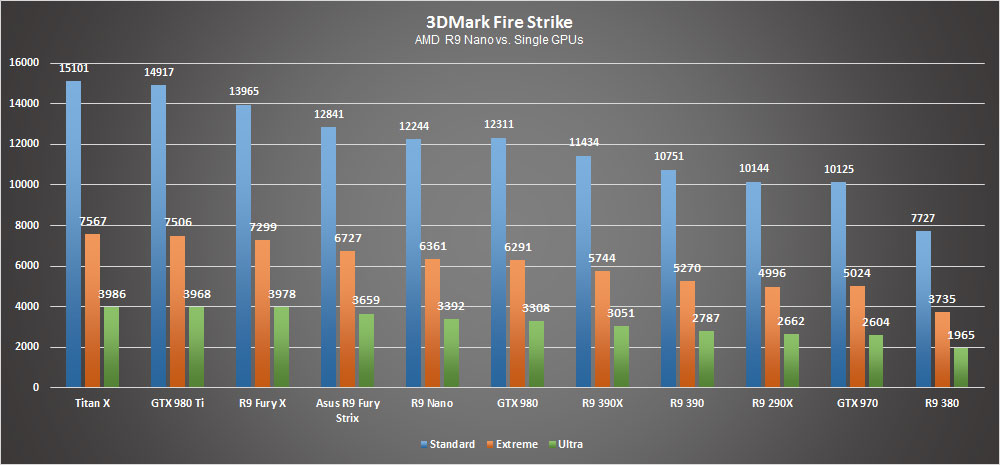

And now we come to the real question. AMD says Nano is up to 30 percent faster than R9 290X and GTX 970, but at roughly twice the cost that’s some seriously diminishing returns. Our own testing uses our standard test bed, which most definitely isn’t a Mini-ITX build, but it helps minimize the number of variables. We’ve trimmed down our tests to just seven games now, along with 3DMark, but we’ll be upgrading to Windows 10 and looking to add some DX12 tests in the near future. Here’s what we’re currently running, along with our results:

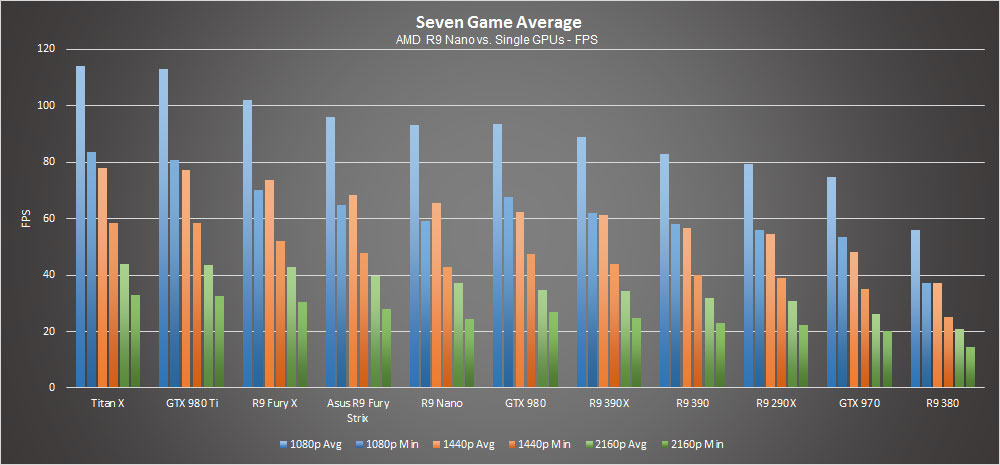

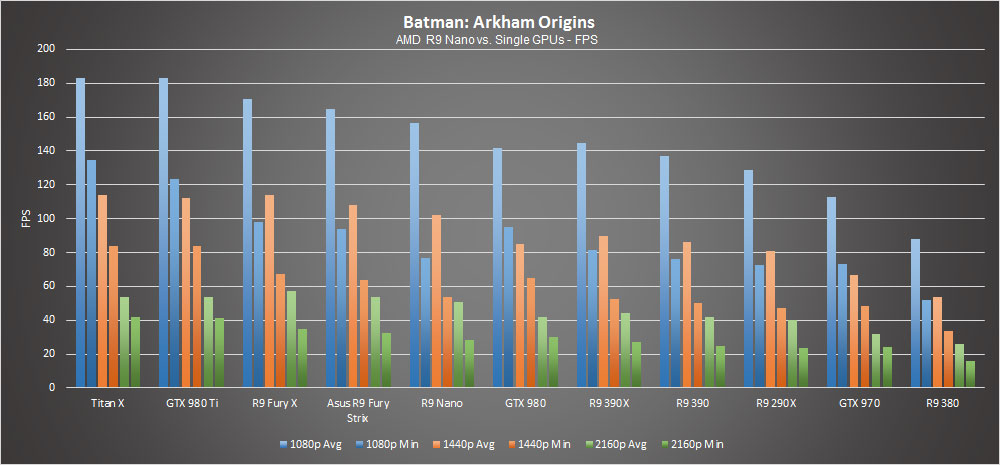

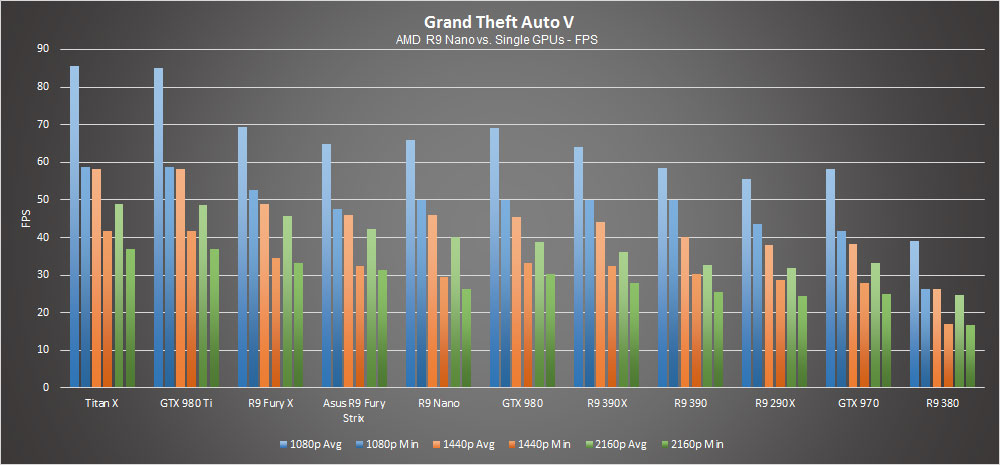

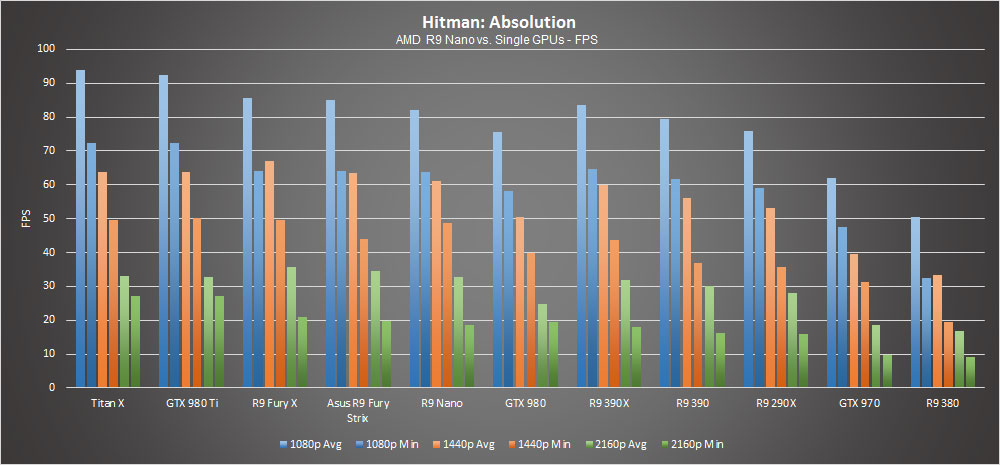

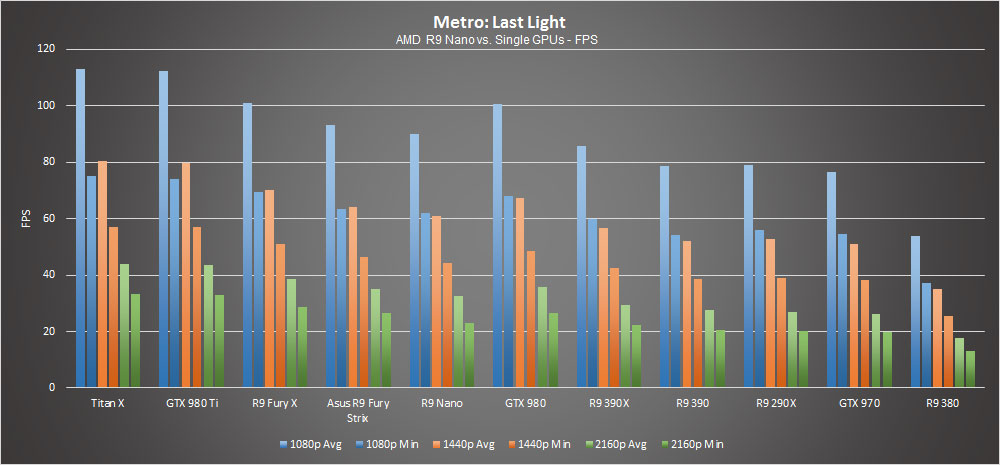

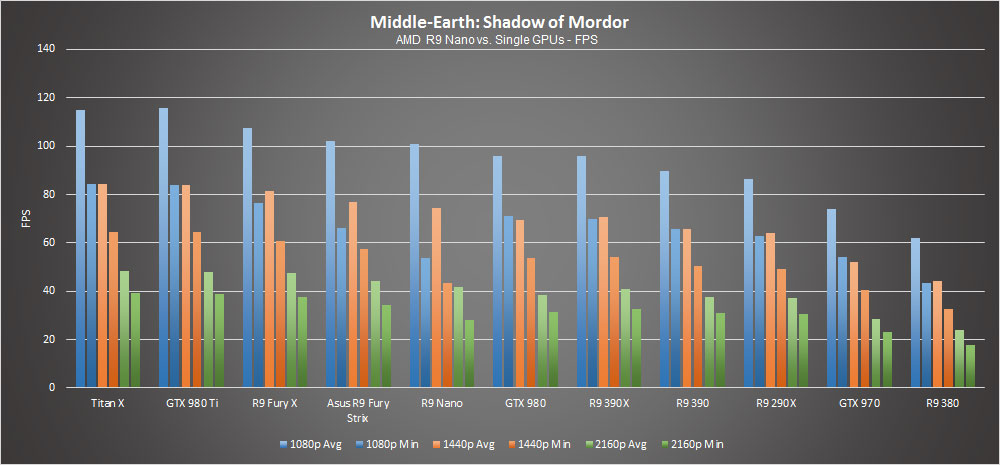

The game, settings, and resolution can all have an impact on performance, and juggling those variables can certainly influence the results. We’re not interested in trying to make one particular brand of GPU look better or worse, so we have our standardized results using a variety of games. What we find is that R9 Nano falls just a few percent shy of the R9 Fury, and about 11 percent behind the R9 Fury X, just as you’d expect from the clock speeds and TDP. The gap also tends to be larger at higher resolutions, which means R9 Nano has to reduce clock speeds more under heavier loads—nothing too surprising there. AMD’s preview of the Nano claimed performance up to 30 percent higher than the R9 290X and GTX 970; our own testing has the 290X outperforming the GTX 970 by 12 percent on average, with the R9 Nano in turn beating 290X by 20 percent on average, and GTX 970 by 34 percent on average.

Other comparisons are also worth pointing out. The Nano is only about four percent faster than the GTX 980, with almost universally worse 97 percentile frame rates (10 percent lower on average). It’s also 16 percent slower than the 980 Ti on average (and manages just a single tie at 4K in Hitman), with 25 percent lower 97 percentile scores. Or if you’re not as concerned with efficiency, Nano is seven percent faster than the R9 390X, 15 percent faster than the R9 390, and 75 percent faster than the R9 380 4GB (at over 3X the cost).

Something else to discuss is the temperature and noise levels. The Nano also targets 75C for temperature, and the fan basically does the work to keep it there. In our testing, the card would reach 75C shortly after loading any reasonably taxing game, but it would never go beyond that level. It's possible in some extreme cases users could push the temperatures that high, but it would more likely than not require overclocking. If the GPU does heat up beyond 75C, there's a second thermal throttle in effect that kicks in at 85C. The net result is that the Nano uses substantially less power and doesn't get nearly as hot as an R9 290X. For our GPU test rig, the Nano fan is also quieter than the CPU waterblock fans, which means not very loud. We'll be shifting to a low-noise testbed for noise/power/temperature testing in the future to better isolate GPU noise.

Without talking pricing and other factors, R9 Nano looks good, and it looks great when you factor in the size of the card. But pricing has to be given some serious consideration. Like the Titan X where you’re paying a huge premium for a 12GB halo product, the R9 Nano commands a large premium for its compact size. It’s not too far off the pace when looking at other $500–$650 graphics cards, but the R9 Fury is slightly faster for less money if you don’t care about size, and GTX 980 is very close in performance with a lower TDP and price. GTX 980 Ti meanwhile delivers substantially more performance and overclocking potential, provided you have the space for the card.

No matter how you want to slice it, the R9 Nano is going after a niche. If you fall in its target demographic, Nano excels at packing a lot of performance into a small space, but for general desktop use it loses some appeal.

A Tiny Overclocked Volcano

With a TDP of 175W, the Nano is going after a far lower power target than any other Fiji-based GPU. Things become interesting when we move on to overclocking, as AMD’s Overdrive utility provides the usual ability to increase the power target as well as clock speed. Where things get a bit iffy is when we look at the maximum 50 percent increase in power target; there’s only a single 8-pin power connection, rated for 150W, plus another 75W from the x16 motherboard connection. That gives us 225W total power delivery, but 175W * 1.5 = 262.5W.

Throwing caution to the wind, we set our sights on warp factor 9.99 with a 50 percent increase to the power limit and a 10 percent increase on the GPU overclock. Unfortunately, after a few trial runs we determined it was too much for the Nano to handle—the tiny volcano kept erupting in our faces. Further experiments ultimately led us to conclude that the real issue was the 50 percent power draw increase, and even a 40 percent increase was still unstable. Most likely the card’s power delivery simply isn’t designed to cope with much more than 225W, though other system components may play a role as well.

Eventually we decided staying closer to the 225W power delivery of the x16 slot and 8-pin connector was necessary and ended up with a 35 percent increase in power target and a six percent increase in core clock. The power limit may have some flexibility, but the maximum core clock hits a pretty hard limit—we saw artifacts even with a seven percent overclock, with everything from a 20–50 percent power limit. Considering the Nano is binned to run at lower voltages than Fury X, that’s probably part of the reduced clock speed range.

What exactly did the increase in power limit and GPU clocks do for performance? We got a pretty consistent 10-15 percent improvement in overall frame rates, which puts overclocked R9 Nano somewhere between the R9 Fury and the R9 Fury X. Additional time spent tuning the GPU core and RAM clocks could help, but without the ability to tweak voltages that’s all we were able to get. And really, overclocking the R9 Nano goes against the design ethos of the card in the first place. The vast majority of users will be better served by a different card if they’re thinking about overclocking—R9 Fury or R9 Fury X for AMD users, or the 980 Ti is easily the most compelling high-end overclocking GPU for everyone else.

Size Matters

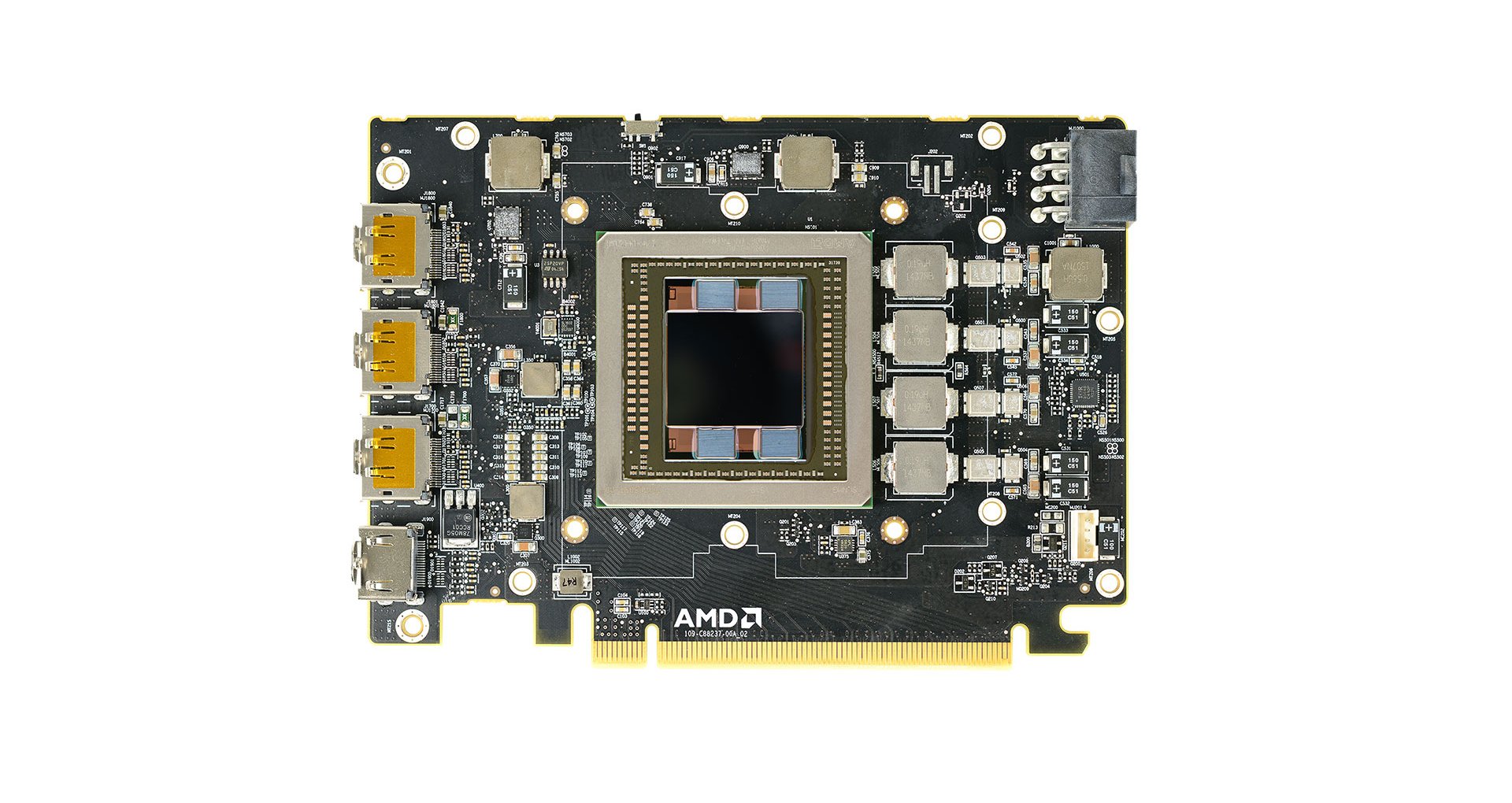

The Nano is really an astounding GPU in many respects. It shows how with a bit of tuning, Fiji can go from being a 275W monster to a 175W tiny terror. Put the Nano next to most other GPUs and you’d expect it to deliver inferior performance, but in many cases it doesn’t. The density and space requirements of HBM are a huge win in this regard; look at the area used for GDDR5 on a 6GB 980 Ti graphics card or even a 4GB GTX 980 and compare that with the Fiji package that contains memory and GPU in less than half the space and you can see why most other GPUs can’t hope to go as small as the Nano. But while there’s no question it’s the fastest GPU in its size class, that doesn’t mean it’s the right GPU for you.

Some people love the brute force approach of muscle cars, and R9 Fury X or GTX 980 Ti will be a much better fit if that’s your thing. The majority of gamers use desktop systems with sufficient room for at least a 10-inch graphics card, and paying extra just to get a smaller, more efficient GPU isn’t likely to grab their attention. Instead, it’s those running truly compact Mini-ITX rigs, and system builders looking to sell such systems, that will find plenty to like in the R9 Nano.

We’re also curious to see where else AMD might try to take Fiji. Giving up 10-15 percent performance to drop from 275W to 175W is really impressive, but what if you want to go even lower…like the 100W limit you’ll find in most high-end gaming notebooks? Another 10-15 percent drop in performance should fit the bill. We haven’t seen a truly new high-end AMD mobile GPU since the HD 7970M, aka HD 8970M, aka R9 M290X. Those are all derived from the Pitcairn architecture that launched over three years ago, and Fiji would be a huge boost in performance and features, even at lowered clocks.

Supply and demand for the various Fiji-based products is also still problematic. The Fury X continues to be out of stock and/or insanely priced, but whether that's due to high demand or limited supply (or both) is not entirely clear. R9 Fury cards on the other hand tend to be readily available at MSRP. If Fury X and Nano are both taking the best-binned chips, it could be that many chips are failing to meet those requirements and ending up as stock R9 Fury. Hopefully the launch of R9 Nano signals an end to the limited availability of the Fiji cards, as there are Fury X buyers still waiting for prices to come down.

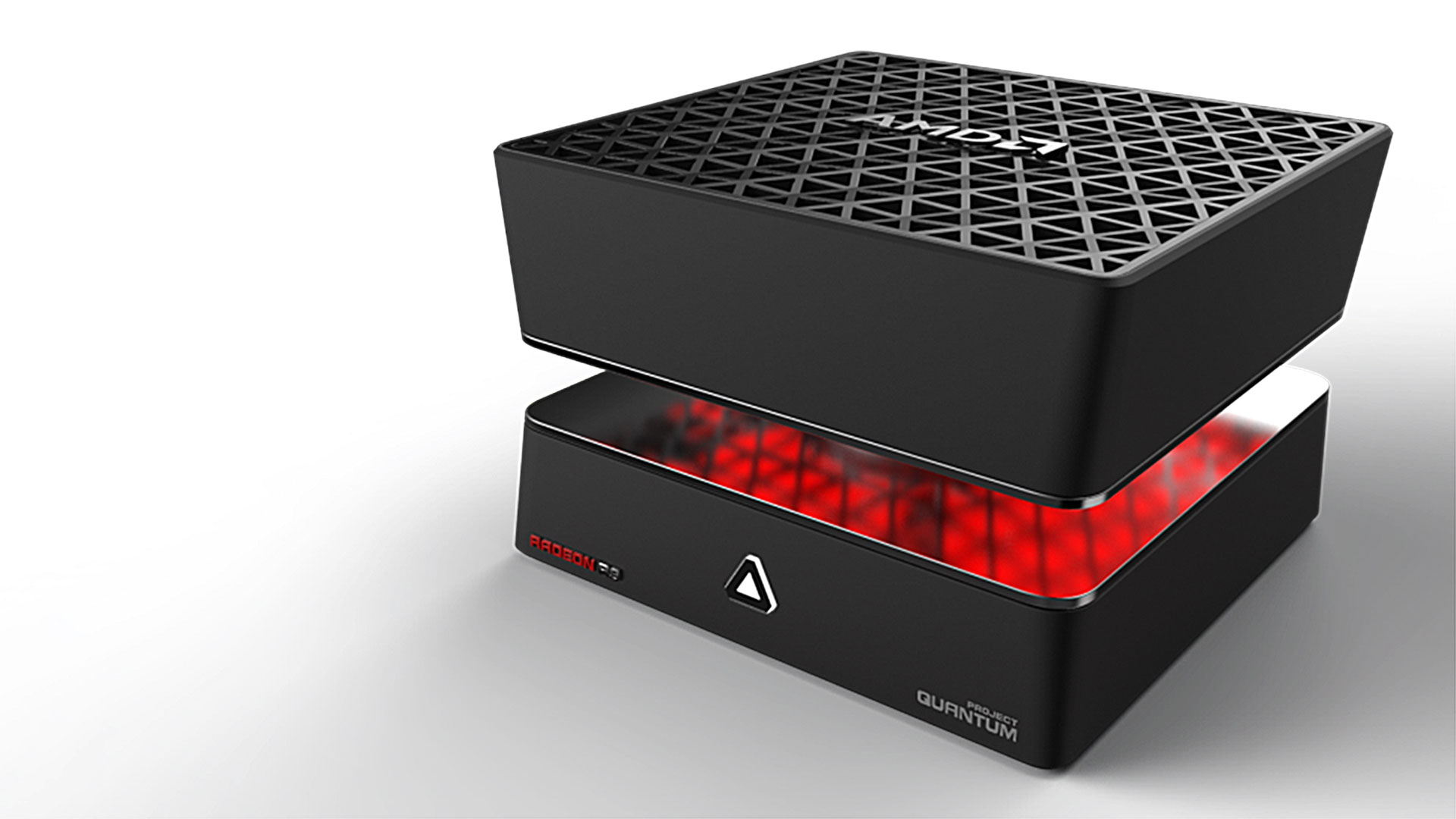

Ultimately, the R9 Nano is a classic case of diminishing returns where spending substantially more money doesn’t net you a commensurate increase in performance, but diminishing returns coupled with diminishing size is something new and different. If you're big on Mini-ITX systems, then this is undoubtedly 95 Kick-Ass hardware; if you're not so enthralled with small PCs, it ends up being a lot of money for less performance and you can knock 5–10 points off the score. We've gone with the intended audience (Mini-ITX fans), but personal preference will play a big role for end users. It will be interesting to see what others do with the concept, and we’re sure to see some outrageous mini-PC builds rivaling even AMD’s Project Quantum.

AMD's Project Quantum prototype

Follow Jarred on Twitter.

The R9 Nano is the fastest GPU ever crammed into Mini-ITX motherboard dimensions, but youll pay extra for the small size.

Jarred's love of computers dates back to the dark ages when his dad brought home a DOS 2.3 PC and he left his C-64 behind. He eventually built his first custom PC in 1990 with a 286 12MHz, only to discover it was already woefully outdated when Wing Commander was released a few months later. He holds a BS in Computer Science from Brigham Young University and has been working as a tech journalist since 2004, writing for AnandTech, Maximum PC, and PC Gamer. From the first S3 Virge '3D decelerators' to today's GPUs, Jarred keeps up with all the latest graphics trends and is the one to ask about game performance.