A brief taste of Call of Cthulhu shows cosmic horror promise

Call of Cthulhu feels like a mostly authentic adaptation, which means you'll probably be insane by the end.

After the first three hours of Call of Cthulhu were over, I was pretty sure that I would be playing game. It was like a first episode of a TV series tailored for my brain: Calculated to draw me in, interest me, and keep me going for a bit longer until I'm fully hooked. "A bit longer" comes soon: the game releases on the 30th of October.

The plot appear to be what tabletop Cthulhu players might call a 'purist' adventure—you’re probably going to end up dead or in an asylum by the end.

It actually took me almost four hours to play through what the developers called “the first three hours” of the game, since I reloaded a couple times to try out branching paths. Call of Cthulhu is going hard on statues of monsters, spooky cultists, and unsettling dreams. It’s not going to go too hard on the sense of cosmic unease or suspense, as you might expect from anything Lovecraft. That’s there, but instead Call of Cthulhu is choosing to focus on a horrid sense of place and gothic decline. For me, that’s two out of three on the Cthulhu story scorecard. That’s not so bad!

Years ago, I questioned this game as a premise: Could it ever really be a faithful adaptation of the tabletop Cthulhu experience? That’s what publisher Focus Home Interactive bills this game as: The Official Adaptation. It's been delayed and seemingly restructured since my first look. Cyanide Studio’s final plot appears, based on the first few hours, more like what tabletop Cthulhu players might call a “purist” adventure—you’re probably going to end up dead or in an asylum by the end. That suits me fine. In fact, I’d be overtly critical if it went any other way in an investigative cosmic horror game.

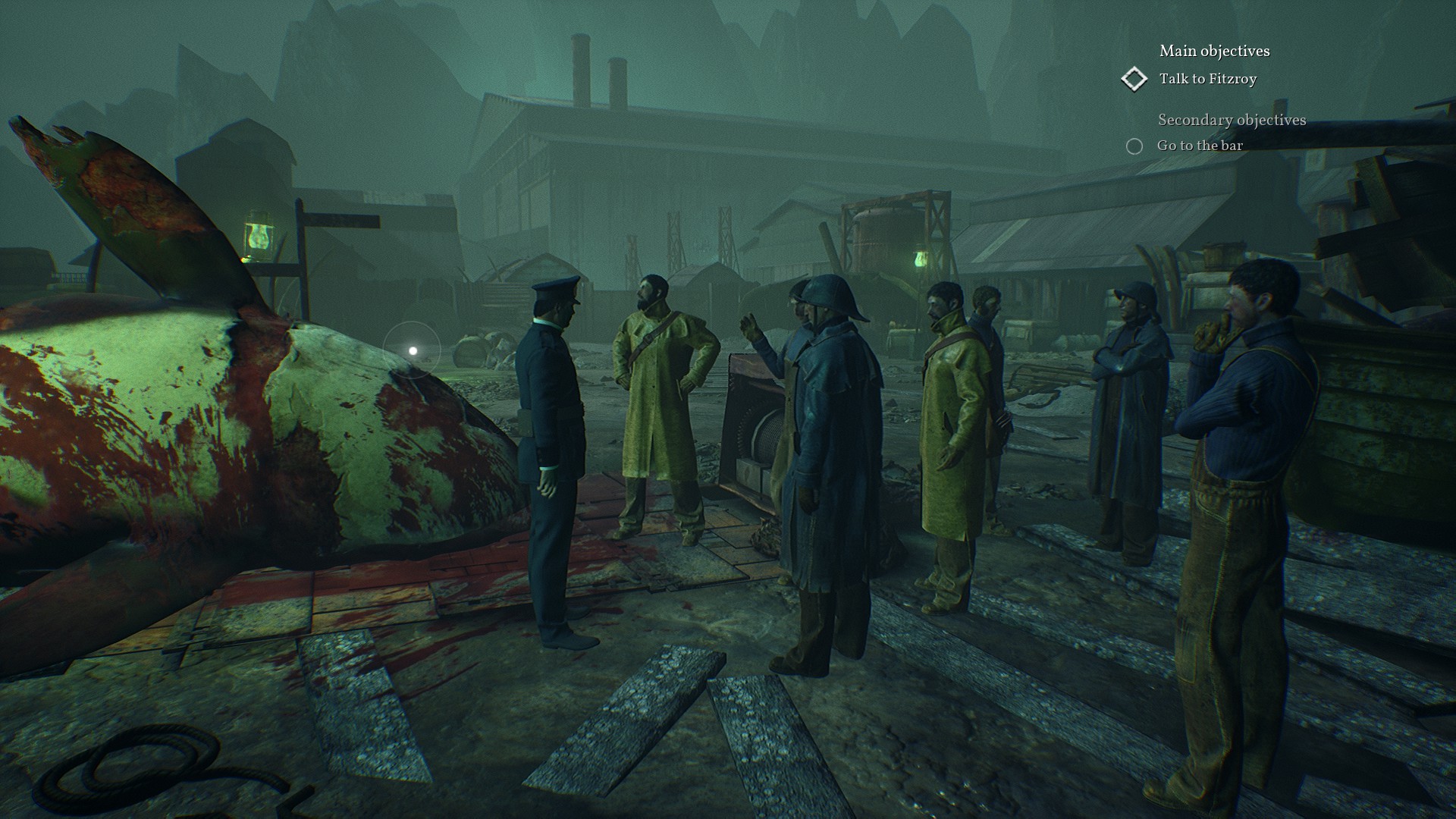

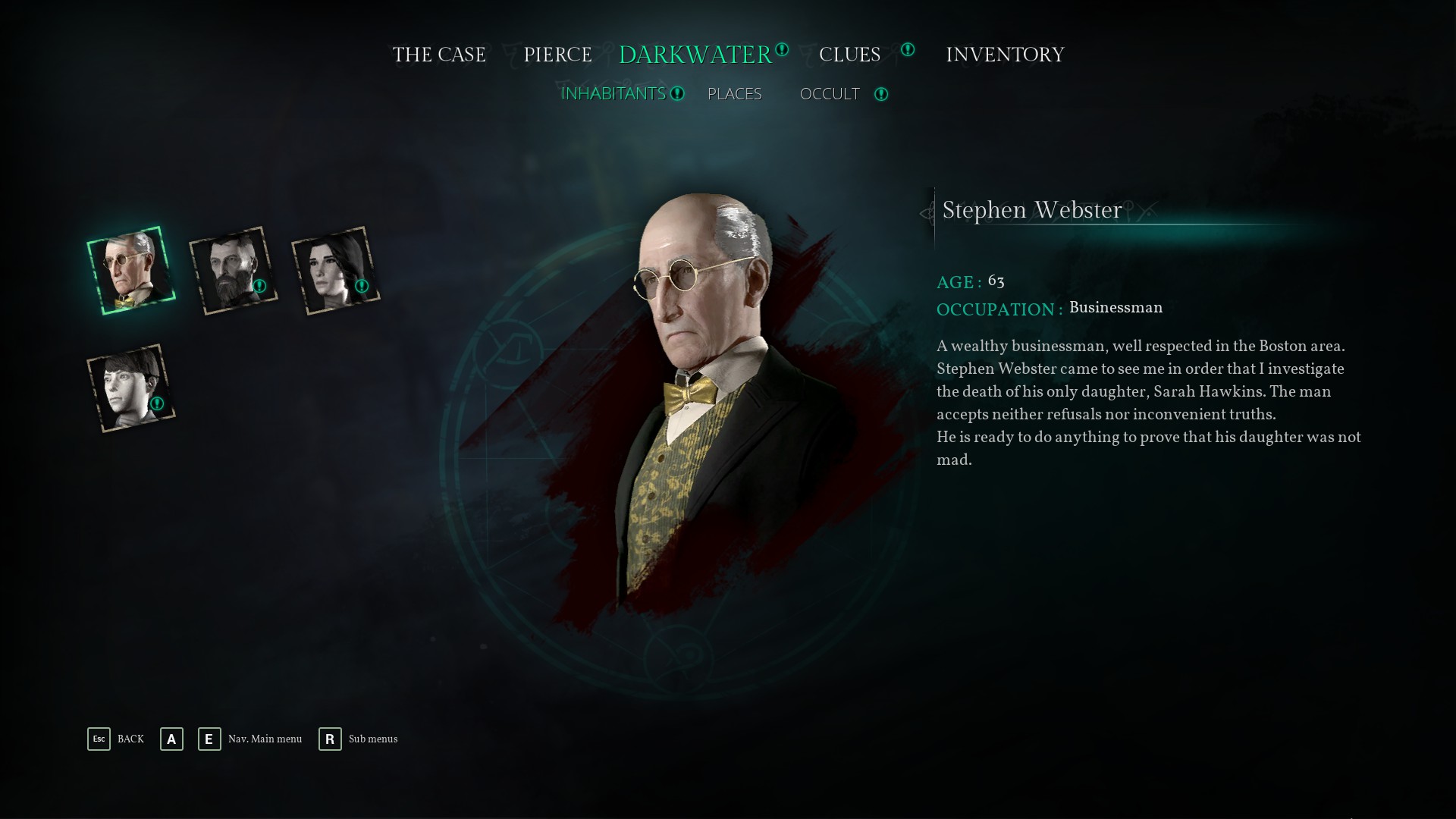

Cyanide’s Call of Cthulhu depicts a 1920s America trying to forget The Great War and sliding surely into the The Great Depression. You play as Edward Pierce, a failing private investigator using drinks and sleeping pills to forget what he saw in the war. You’re sent from Boston out to remote Darkwater island to find out the fate of the Hawkins family, burned to death in a fire in their mansion. Darkwater is a perfect 20s locale: Remote, desperate, and decaying, an island slowly falling apart since the end of the golden age of whaling nearly 80 years past.

Call of Cthulhu has attention to historical detail in many places—especially in clothing and material culture, the look of books and guns and boats and buildings. It’s what you need to claim the CoC tabletop legacy, which has always been a period piece, and on that front it's a big success.

The demo falls short in other places. An artist’s drawings and paintings look much more like video game concept art than any school of painting active in the 20s. The voice actors’ accents are a butchered combination of standard American English with an occasional Massachusetts twists. A heavy film grain gives an aged look to the whole game, but it doesn’t do much for limited, oppressive, and muted color palette Cyanide has chosen.

The characters I met in the first few hours on Darkwater island were an interesting mix of stock horror types and a few twists I was grateful for. For example, there’s an uncooperative, nigh obstructionist, police officer... who later turns to your side. Or a tough, distant femme fatale… but she’s the boss of the local bootleggers rather than a link in the investigative chain.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The actual action of controlling this game as you go about your investigation is nothing too special, but it doesn’t really have to be. It’s a game that will live or die on its plot and visuals. It’s still very much going to be what James saw last year and called a walking simulator RPG with investigative and horror elements. You spend a lot of time walking, talking, out-talking, talking to yourself, and doing skill checks against your RPG stats to find things or open doors.

There are small branching sections in the early part of the game, but they really don’t seem to change much unless Call of Cthulhu has some deeply buried Witcher-esque plot turns based on early actions. It’s not a sandbox kind of mystery, nor does it seem like it’s going to do much more than linear horror games or exploration games it draws so heavily from.

For all that, I did feel like I was in a tabletop CoC adventure. I blundered around, talking to anyone who seemed relevant. I vacillated on which scheme would most likely accomplish my goals, tried stealth and failed, then tried to talk my way out of it and failed at that, too.

Skills, you see, have a very low chance of success most of the time. Like really bad shots in XCOM: We’re talking 30 percent or less, closing in on 40 percent for your best stuff. That means if you try to sweet talk someone, or pick a lock, you’re going to be very thankful when you succeed. Some skills, like Occult or Medicine, can’t even be increased with your skill points. You have to find objects in the world to increase them. Because of that, I really felt like an investigator—I found myself checking under every table, on every bookshelf, and behind every door. The monotony of this was, at least in the short term of the demo, well countered by the terror that I knew could come at any moment.

One quibble though: Everyone knows not to read books in Call of Cthulhu. This Pierce guy picks up every book he sees, and if that ends with him not going stark raving mad, l I’m going to be pissed.

Jon Bolding is a games writer and critic with an extensive background in strategy games. When he's not on his PC, he can be found playing every tabletop game under the sun.