West of Loathing's first hour redefines how we engage with open worlds

One of the year's funniest RPGs is also its cleverest.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

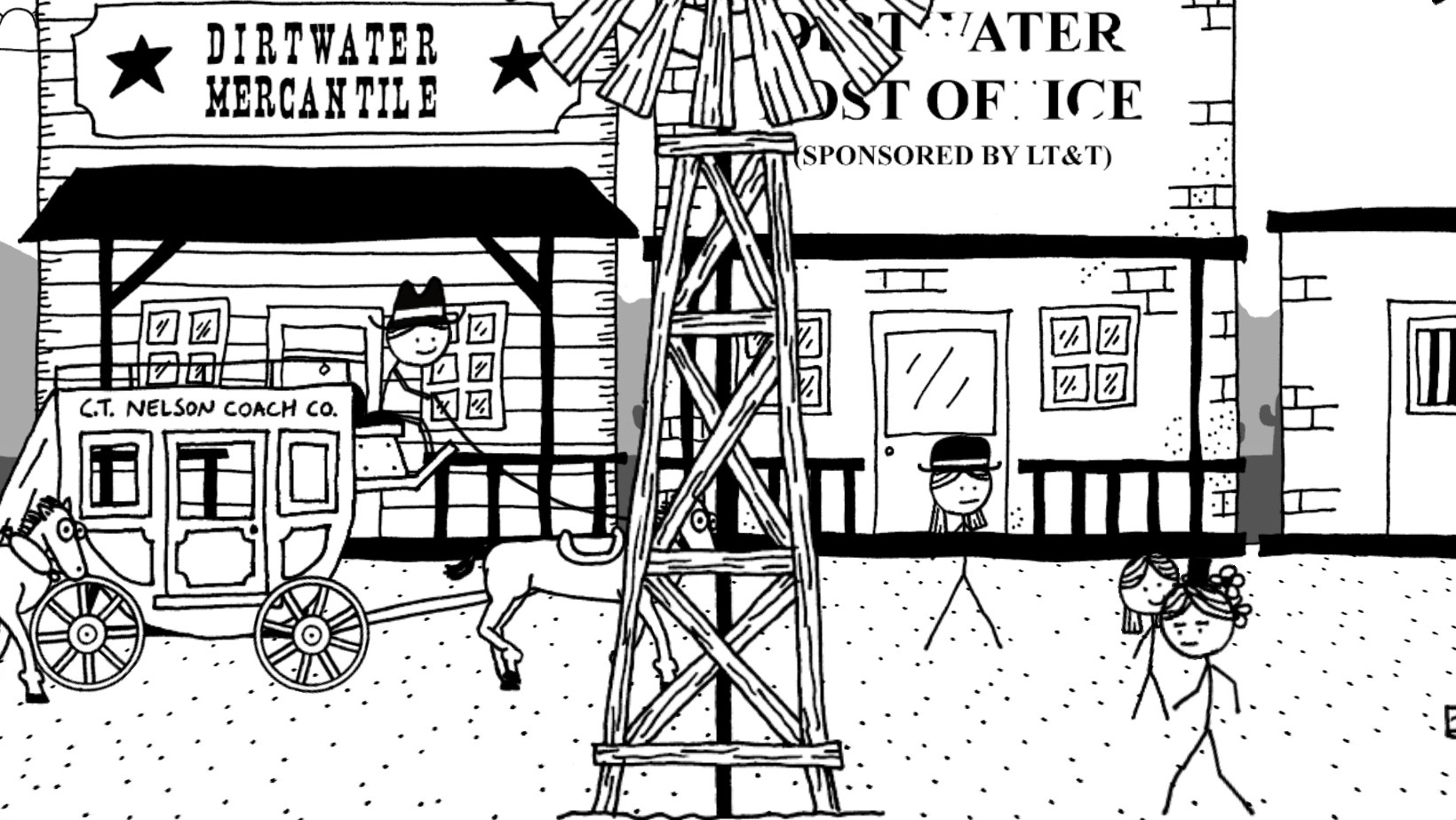

Seems like another ordinary day at your typical Loathing farmstead. You wake up, comb your hair (netting you a single XP), speed-read a manual on the finer points of Stupid Walking (acquiring the corresponding perk in the process), and solve a puzzle.

But then you have to stifle a sob before joining the rest of the family, already gathered outside for your departure. Today is the day you leave home to seek fame and fortune in the scattered pockets of civilization dotting the deadly desert to the West.

It's a fairly ordinary setup, right? For several years almost every JRPG under the sun started more or less the same way. Still, there's something funny about those first minutes of West of Loathing—not in the sense of ha-ha funny, but something ever so slightly different. Something off.

Asymmetric's quasi-sequel to Kingdom of Loathing is frequently hilarious, but for all the praise, it must be just a tiny bit frustrating how everyone seems to concentrate almost exclusively on the jokes. I mean, it's not like a game could be the funniest thing we've played in years and the most brilliant subversion of RPG tropes in recent memory, as well as an astute commentary on contemporary open worlds at the same time. Could it?

Just as impressive as the ways West of Loathing defies tradition is how subtly it attunes players to the demands of its own logic in two brief introductory areas. In order to avoid major spoilers I'll focus mostly on the starting farm and the small settlement of Boring Springs to outline how West of Loathing explodes calcified generic conventions and emerges as not only the funniest game of 2017, but one of the most complex and intelligent, too.

Meaningful repetition

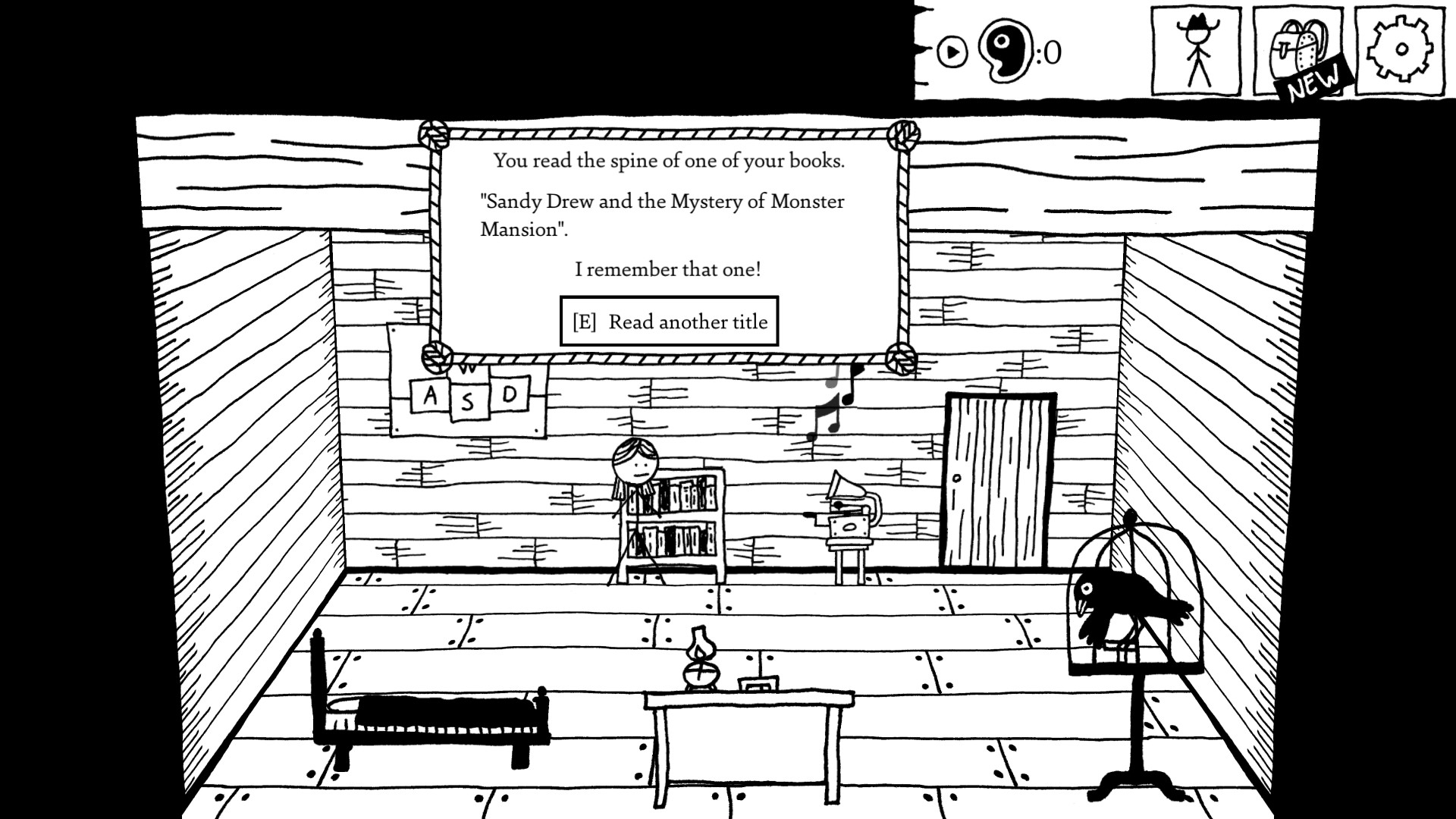

Surely I'm not alone in this: Whenever I see a response repeated, in dialogue with an NPC or as descriptive text after investigating a piece of scenery, I assume that particular interaction has been exhausted. While the infinite books available back at the farm are not identical, with titles like "Calvin Danger and the Mystery of Witch Woods" or "Clara Hardy and the Haunted Lighthouse" it becomes obvious they are randomly generated—as strong an indication that there's nothing to see here as strictly defined repetition.

Yet, if you persist for several clicks (six, just enough so that the similarities will have registered, but maybe not to the degree of putting you off) you're rewarded with the manual on Walking Stupid.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It's hard to overestimate the importance of this formative, early experience in shaping your attitude for the rest of the game. An unspoken rule that has dictated player behavior for decades is rendered null and void, and interactions that would be considered meaningless elsewhere now seem pregnant with possibilities.

After exchanging your farewells, you have the option to repeatedly hug your mom. Will this have a practical effect—perhaps producing a batch of home-baked cookies she forgot to give you earlier? It doesn't (at least I don't think it does), but the suggestion it might is already stuck in your subconscious.

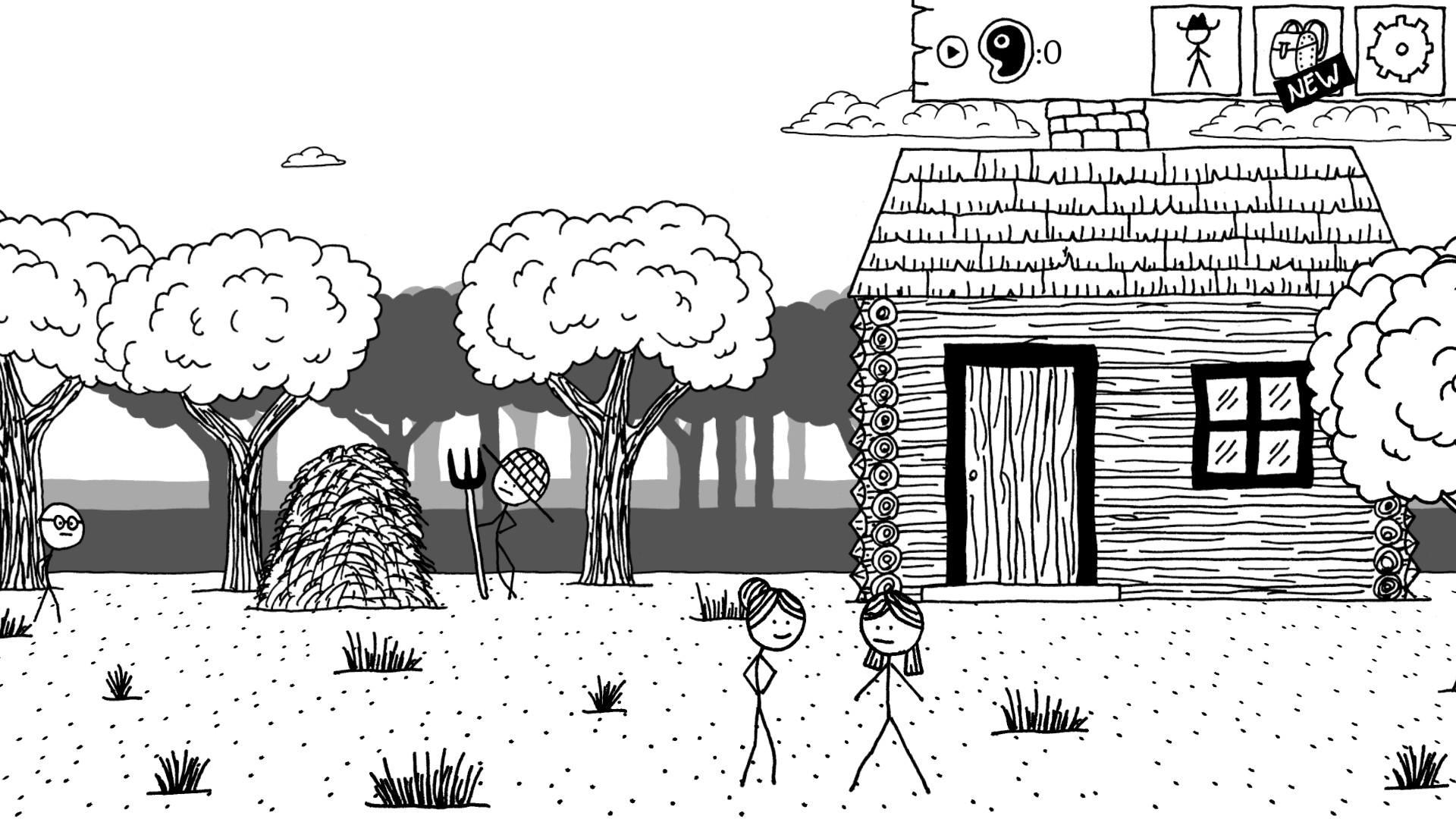

After implanting the idea in your mind West of Loathing refuses to establish it as a rigid general rule. Some repetitive actions are rewarded, some are not. The small town of Boring Springs is filled with cactuses and horse turds, and after bumping into around 20 cactuses you acquire the Mostly Scabs perk, raising your overall HP.

Which, naturally, means that you'll gleefully keep stomping on horse poo until you realize there's nothing to be gained by it. The point here is not to reward mindless repetition through a norm just as unexciting as the ones West of Loathing is subverting—the point is to create uncertainty, to prevent you from taking anything for granted. And also to make you stomp on some turds.

Hidden causalities

There's no better way to have uncertainty grab players' imaginations, and make every interaction seem potentially meaningful, than obscuring the chains of cause-and-effect begun by those interactions. Most locations in West of Loathing feature some tidbits of information or a seemingly inconsequential action that will trigger a change elsewhere in the world. What's important is that these changes are rarely signposted and, on many occasions, actively concealed.

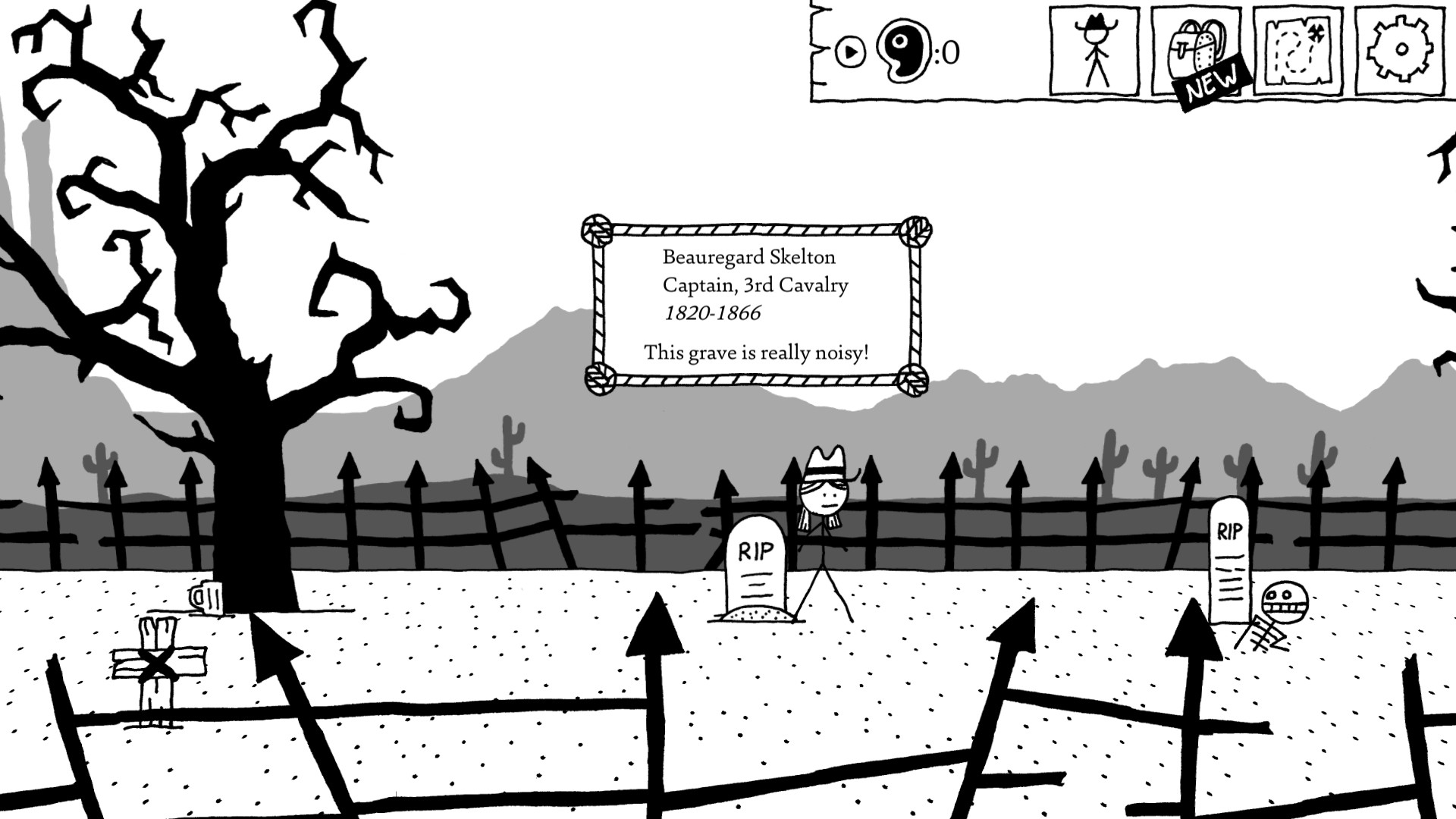

Susie Cochrane can be found brooding at the Boring Springs saloon. Her whole family's dead, so it's understandable that attempts at idle chat will be unwelcome. Hidden, however, among the various tombstones of the local cemetery are three wooden crosses dedicated to Elizabeth, Silas, and Timothy Cochrane. Crucially, nothing explicitly differentiates those from their neighboring memorials—there's just the name of the deceased and a short epitaph. Only if the player registers the surnames and makes the connection, then attempts to restart a conversation will Susie unlock as a companion—along with a new quest and location that would have otherwise remained unavailable.

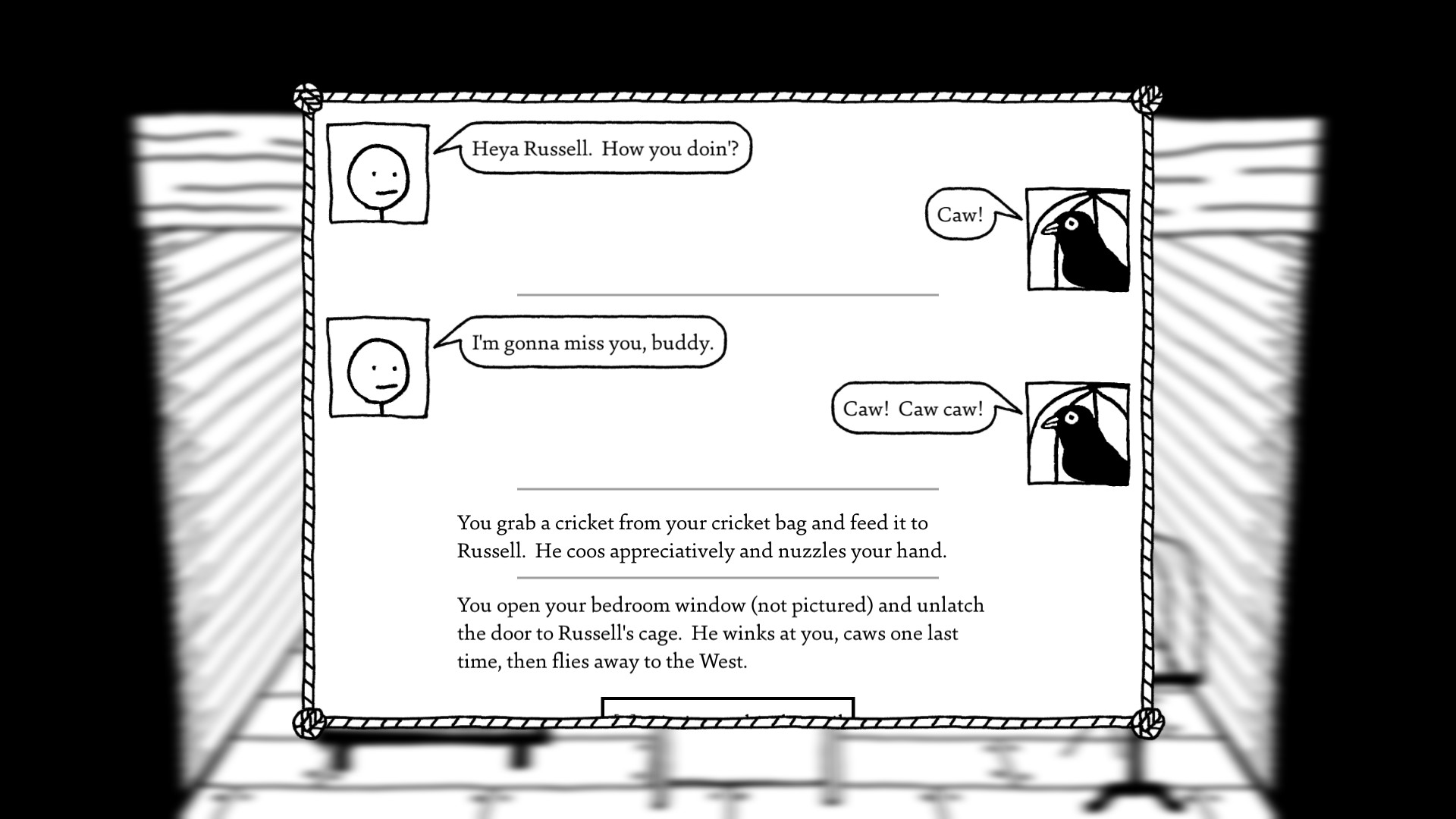

Hiding substantial chunks of game behind seemingly inconspicuous interactions charges every trivial incident in West of Loathing with the promise of numerous unseen possibilities. Another example: before leaving the farm you have to decide between keeping your pet crow Russell in his cage or setting him free. How does your choice affect the story?

As of my third playthrough I still don't know what happens to Russell the crow.

Aggressive misdirection

These hinted possibilities, hidden stories, and unexplored locations are the main reason why West of Loathing is an immensely replayable game. You're prevented from quickly exhausting the game's possibilities through its third core subversion: aggressive misdirection.

A pesky humanoid has occupied the basement of the Boring Springs saloon and the proprietor is predictably furious. His familiar plea (and the game's first proper quest) is to get rid of the invader. A typical course of action would be to immediately descend into the creature's lair (it's just next door, after all), and dispatch it with ease. It's what I did.

Hidden, however, somewhere in the cluttered basement is a bottle of whiskey. After hanging around town a bit longer you learn that the local doctor, whose house you may have previously been refused entry to, will only accept visitors bearing the gift of alcohol. Among the books you can leaf through in her library, one teaches you the basics of goblintongue. Oops.

Notice how sadistically you're prodded in the wrong direction by the hapless goblin being conveniently nearby, and the lost possibility of a non-violent solution being rubbed in your face. Communicating with the goblin would have taken an entirely counter-intuitive response to the bartender's plea (searching the basement without killing the creature, then leaving to explore the town) and now, for all but the most atypical of players, the chance is gone. Meanwhile, a relentless autosave finalizes the effects of this and every other decision.

There are so many other examples. What complicated trajectory do you have to follow to acquire the coveted Silver Pocketwatch? Is it even mathematically possible to amass the necessary dynamite to get to the metal box buried inside a crevice in Orehole mine? Chances are you'll have to search for these answers in a subsequent playthrough, but your first time around they'll remain inaccessible because of some decision you made that, at the time, seemed completely unrelated.

West of Loathing's tutorial is not about introducing you to its simple combat system and straightforward level progression—it's an organized attempt at eradicating preconceived notions of how to navigate non-linear environments. It's a brilliant commentary on how content we are to sleepwalk through contemporary open worlds, mass-completing meaningless location-based quests, then mechanically proceeding to the nearest map icon.

These experiments with structure, reassuringly concealed behind a humorous, accessible facade, do more than make it of the most original RPGs in recent years. The exclusion from numerous quests, locations, and narrative threads, the knowledge we are already missing out from the get-go, can be a surprisingly liberating thing. That metal box in Orehole mine will remain maddeningly out of reach, the door on the second floor of Boring Springs' saloon inaccessible, and in another town and another series of quests the local jail will still have vacancies even after you've locked up members of every gang in the vicinity.

It rains these tiny failures on you, each telling a more compelling story than the automatic triumphs of other open worlds, each offering another reason to dive back in after your first journey is done. Paradoxical as it may seem, West of Loathing's aggressive misdirection, its willingness to let you miss out, and its unyielding autosave all merge into the gentlest of messages: that it's OK if you make a mistake.