The making of EVE Online

How Icelandic visionaries made the multiplayer space game and story generator a reality.

Mine craft

Even though the team put themselves through sleepless nights and cashless days in the name of EVE, Reynir maintains his shock that people cared about the game. “That surprised me: the level of passion for the game right from the get go.” Forums and IRC groups sprung up to discuss the impending title. “Before release you just had to say one sentence and everyone got it. People had such a keen idea of what the game would be, they were able to fill in the gaps.” Those players involved in the beta stuck their tendrils further into the universe than even the developers could manage. The fans started to understand EVE better than the creators.

“EVE was a very simple concept. It's a structure: you mine minerals to make ships, which you can then use to mine more minerals. It's a perpetual machine. From that, all kinds of things arise.” It wasn't meant to be a game, Reynir assures me—it was designed to be a toolbox to enable multiplayer experiences. I ask Reynir whether EVE then shaped itself, or was guided by development. “Both. We forged the fundamental rules and vision, then EVE shaped itself to a large extent. We have a lot of input from the community.” Torfi is blunter. “The players took over on May 5, 2003.” Launch day.

Kjartan Pierre Emilsson was one of EVE's early designers. “We talked a lot about chaos theory,” says Reynir. A layman's explanation of the concept: anything that might happen probably will and oh pissfuck, it's happening right now. I glance out of the window at the darkening sky and imposing, inhuman slab of rock on the other side of the bay. In this land of fire and ice, I can see why trying to understand chaos has its benefits.

EVE's first pioneers learnt, adapted, and developed new customs. They were flying electronic spaceships sat in their rooms at home, so they didn't need to get their heads around the tricky combo of 'fire' and 'the wheel', but their emergent behaviour still shocked Reynir—their chaos in play. Mining is his example. “People would reach a system, eject their cargo containers, mine their ore into them, and keep going. Then one guy would warp in and pick them up. We thought that was brilliant .”

CCP's first development team was small and agile enough to respond quickly to player trends. Torfi recalls the era with a definite fondness. “Sometimes I miss being all together in the same room and being able to shout, 'Guys, it's not going to be sci-fi—it's going to be dragons in space now',” he laughs. “When we were still seven horny guys in an attic, a cigarette break could lead to a major shift in vision or goals for the company.”

Seven years down the line, the chances of EVE sticking to its first template are nonexistent. Was there even a long-term goal? Hilmar responds. “We had a long-term wish.” It's agreed in the business of universe creation that it's best not to plan too efficiently so as not to stifle your new residents. Later, Torfi explains exactly how CCP plots out EVE's route. It involves leaving children to die. “It's about scoping to your abilities. Sometimes you do it consciously, sometimes you do it under deadline where you have tons of amazing ideas and you can only pick two of them. Like having 10 perfectly healthy smiling children and having to take two with you before your planet blows up.” Torfi looks increasingly confused as he drops infant-murdering similes, like his mouth is betraying him. “It's a tremendously painful process!” he tries to assure me. Too late.

Battle royal

The features that are included in each EVE update have to be carefully balanced. Reynir explains how, at launch, mining—seen as overly passive—was designed that way: “There's nothing to it, there's no minigame to play. But when you're in dangerous sectors, you feel like you're trespassing, even if nothing happens.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Hilmar leans in again with another take on it. “Because it's so passive, people have so much time to socialise and communicate. They're naturally filling the vacuum.” The mining mechanic is the perfect confluence of developer-led decision making and community-led chaos.

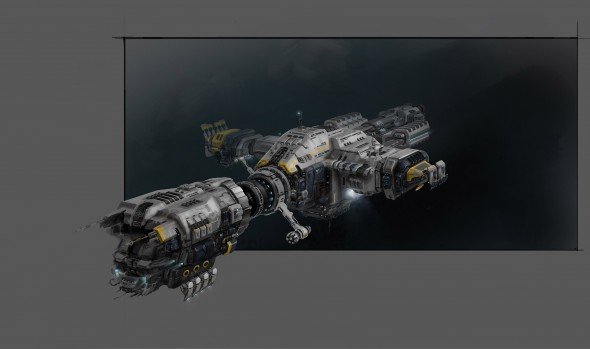

Arnar Gylfason—EVE's senior producer—touches on another behavioural trait that years of theorising and designing skipped entirely: alliances. EVE's social structure is stratified into a few levels. Corporations are closest to other MMOs' guilds in playerbase, but humongous intercorporation alliances can swell into the thousands. “We didn't anticipate players grouping up to the extent that they have—seeing player alliances of 5,000-plus players, perfectly organised, taking over huge swathes of space and maintaining perfect logistical networks.” Fleet battles with 500 participants became commonplace, players wanting to club together for safety, for commerce, and for the greatest chance of seeing a whole load of spaceships blow up all at once.

Fleet battles are EVE's trump card. The greatest of these have become folklore, scenes powerful enough to yank the eyes of people who'd never willingly play internet spaceships. Thousands tune into the Alliance tournament livestream, as Derek Wise—EVE's senior technical director—excitably informs me. He explains how the pilots involved fly wildly complex ship variants into battle. I can feel him straining to tell me more, explain the benefits of exact fittings, but my simple grin when he describes how a gang of drakes isn't always the best PvP option warns him off. It's comforting to see this level of genuine passion, especially from someone exposed to the game's inner guts on a daily basis.

Reynir's getting excited now, gesticulating down the camera. “We have warfare that lasts for years, involving thousands of people. There's propaganda!” He tries to remember the largest number of ships involves in a single fleet battle and mumbles numbers. Hilmar leans in and—half proudly, half fearing for the reaction he'll set off—corrects him. It's 3,400. Nearly three and a half thousand people sat in their rooms, but also sat in space, watching the same scene unfold from different perspectives, living the same experience from their independent viewpoint. I'm excited just about the verbalisation of the concept.

Making headlines

I know this excitement well. That maxim about Deus Ex—every time someone mentions it, someone else has the urge to install it—also applies to EVE. Unlike any other game, EVE has generated stories. In November 2010, the SOMER Blink Corporation was played out of 110 billion ISK (EVE's in-game currency) by a longterm friend of the corp's leadership. The news hit most major gaming sites within hours of confirmation, joining a host of similar stories. I asked the team for their favourite EVE event, one that pushed outside the game boundaries to reach wider gaming consciousness. Arnar recalls a specific time early in EVE's life, when a set of hyper-organised bastards camped moon-gates, sniping incoming enemies like highwaymen.