Five Tricks Developers Should Use To Help Disabled Gamers

Usually, game jams are about pure creativity, albeit with a theme; they're to challenge developers to think outside of the box. Sadly, as most disabled gamers know, the biggest games companies are usually the ones who are the least creative about accessibility, if they think about it at all. This year's Global Game Jam, the world's biggest collaborative development session, changed that up, featuring an accessibility challenge, with aim of raising awareness amongst the development community of the barriers facing disabled gamers - and how straightforward it is to avoid them.

Designer & accessibility consultant Ian Hamilton co-ordinated the UK challenge on behalf of the IGDA and he explained how it's a deceptively simple problem. “The common misconceptions about game accessibility are that it is difficult, expensive, dilutes the proposition and only benefits a small minority. In reality, 1/5 of the average gaming age population is affected by a disability, and the kind of considerations involved are often simple design decisions that make the game better for everyone, and cost very little time or money if thought about early enough.”

Though AAA companies sometime make one-off accessibility efforts, like Treyarch's colour-blind mode for Call of Duty: Black Ops, Hamilton emphasises that events like these are needed to raise awareness; “The red/green colourblindness that Treyarch addressed affects 8-10% of males, meaning they were finally able to tell their team-mates from their enemies. Even just a few minutes thinking about each of the four types of disability - motor, visual, hearing and cognitive - at the outset of a project can make a huge difference, as all of the Game Jam games demonstrate very well.”

Here in the UK, designers, developers, sound producers and artists spread across seven locations were given advice and accessibility mentors to help throughout the event, and split themselves into 20 teams to come up with new, accessible designs for games. We caught up with five of the developers and mentors to find out what their top tips for developing for the disabled were.

1. Hearing: Subtitles and visual cues

Lynsey Graham, a designer from Leamington Spa's Blitz Games Studios, talked us through designing for hearing-impaired players; “Good subtitles and visual cues can make the difference between a fantastic game and an unplayable one for a gamer with hearing impairments. Subtitles should not only feature the dialogue, but also give some indication of context. Is that line of speech coming from a character that's physically near the player, or across a radio? Who's talking? Can you see their facial animation to tell whether they're being sarcastic or sincere?”

Graham also emphasise the need to duplicate the cues for sound effects visually, so those with hearing impairments can keep up; It's all about providing alternatives to sound. “If you have an audio cue for an event that isn't accompanied by a visual cue, then those with hearing difficulties are going to miss a key bit of information. Reinforcing important information with both sound and visuals is good practice in general – for all players.” Finally Graham recommends: including character names or portraits in any subtitles, so the player knows who's supposed to be speaking; subtitling off-screen sounds and events; and including both visual and haptic (that is, force-feedback) cues for game critical events and information. These things are helpful to a great many people, including everyone who plays with sound muted or even just has a noisy house. Subtitles are proven to earn you extra sales.

2. Motor: remappable controls

Barrie Ellis, a technical specialist at disabled gaming charity SpecialEffect, gave us a few tips for helping out gamers with motor control issues, like Gareth Davis, the disability campaigner we interviewed in early 2011. “Offering players a flexible way to reconfigure game controls, and ideally a way to reduce the controls if needed, takes into account those who play in non-standard ways.” says Barrie. “Such people include left handed players and those reliant upon custom controls. Without such a feature, games can be uncomfortable to unplayable.” Remappable controls are simple to include and standard practice for PC games, but currently rare on consoles. Such players also especially benefit from difficulty levels that affect speed or length of time available.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

3: Cognitive: flexibility

Jake Manion is the Assistant Creative Director of Aardman Digital, part of Aardman Animations, creators of Wallace and Gromit. He gave us some tips for helping out players with cognitive impairments. Given this covers such a large range of players, the tips in this field are almost be good tips for developing games in general.

“Use ability-sensitive hints and play settings that aren't simply limited to 'easy, medium, hard'.” says Manion. “Let the player decide for themselves which aspects make a game too hard or too fast. Allow players to experience your games without fear of failure, if they wish. Configurable games can be enjoyed by a far wider range of abilities, and are usually enriched by the unexpected gameplay that emerges.”

4: Visual: Contrast

Tom “Fanotherpg” Kacmarek, winner of the London challenge, is a solo developer from Poland who works out of Buckinghamshire New University. “A great deal of effort is put into visuals, but they're not always accessible. At the Global Game Jam, we demonstrated how options such as a Fallout 3 style high contrast interface (or even just better contrast by default) can be very easy to implement and help many people - so why not include them?”

Another easily solved issue for people with visual impairments is being able to read text – simply use clear well contrasting fonts and make sure that they're a decent size. A simple option for whether or not to scale with screen resolution helps.

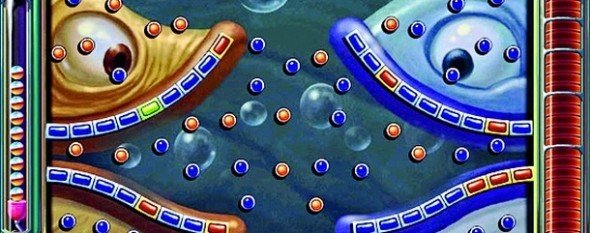

5: Colour-blindness: Patterns and Palettes

As a colour-blind gamer, I've long found that the industry doesn't think about disability; almost every time I go to a preview event, I have to point out to developers that their colour scheme doesn't work. Tom Parry, the Lead Artist at Bristol-based Mobile Pie, was part of the winning team at the Bristol jam (you can play their game here: http://globalgamejam.org/2012/super-space-snake-space/play). He isn't himself colour-blind, but worked along side programmer Daniel Twomey, who is and was able to test the in-game colour schemes.

Parry explains “Catering for colour blind gamers can be easily achieved by implementing a few things: using shapes or patterns to represent colours, creating high contrast between sprites and backgrounds and staying away from red/green, red/black and blue/yellow combinations.”

Colour blindness affects huge numbers of people, caucasian males in particular, meaning that for example red and green both appear to be brown instead. Not thinking about it can make your games unplayable. The most common culprits are use of colour alone to indicate friends/enemies in deathmatch or on a mini-map, to show good/bad racing lines, or to distinguish objects in a puzzle game. Great examples of how to solve it are GTA's symbol based map, or Peggles's colour-blind mode which increases contrast and adds symbols.

General Tips

Just as important an issue as the features themselves, and one that Gareth Davis brought up over a year ago, is for developers to include accessibility information on their box and on their website. PC Gamers can't return opened high street games and especially not downloaded games; letting them know your game is accessible means they won't waste money on games they can't play - and that your game can reach as many new players as possible.

It's notable that the tips the developers gave us are all easy to implement and almost all developers have some awareness of the problems disabled gamers face - they're just not always sure where to start, or assume (incorrectly) that lots of development time would be needed. Yet, given the extra sales and positive word of mouth in the disabled and wider gaming communities generated by making your game accessible, it seems a madness for a team not to take people's different needs into consideration.

As Hamilton puts it; “Although many AAA studios such as Splash Damage, Bioware, Valve, Blizzard, Bethesda and Team Bondi are are starting to do some great individual things, supported by the fantastic work of groups such as the charities Special Effect and AbleGamers, we're still lagging far behind other industries such as web or construction. However access to entertainment, culture and socialising is just as important as access to services and buildings, so game accessibility gives us a fantastic opportunity not just to reach new audiences but to make a real difference to people's lives.”