Will Wright at BAFTA: the creator of The Sims on his influences and hints to his next game

BAFTA have been supporting computer games for years, but they're now making efforts to expand their membership and visibility into America. Which is weird, for an organisation with "British Academy of" in its name.

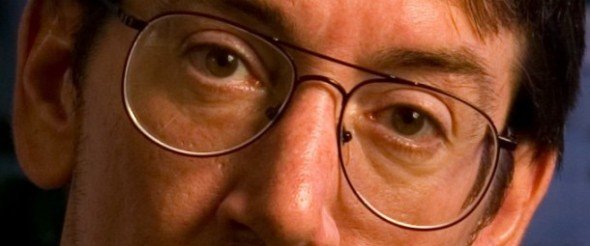

But their first step is a series of profiles called A Life In Pixels, looking at some of the people most important to the development of videogames. The first, with Will Wright, just took place at Raleigh Studios in Hollywood this Sunday evening. I was there, listening to creator of SimCity, The Sims and Spore talk about the power of obsession, the wisdom of ants, his love of hard science fiction, and just a single hint on what his next game project might be. Read on for a full report.

The interview began with Wright talking about his early life and how it led him to become a game developer. He explained that, growing up, every 6 months or so he would get obsessed with a new topic: from Houdini's lockpicking to World War 2, some of the subjects were narrow and some were broad. He's continued doing the same thing his whole life.

"When I enter a new place or see a new thing, my first question is, 'How does this work?'", eplains Wright. He begins reverse engineering the world around him - a habit which he refers to as a kind of affliction. "It's very distracting."

But it also gives him enormous curiosity. At university, Wright studied architecture, aviation, mechanical engeering and psychology, and although he eventually dropped out without a degree, the breadth of his interests has served him well as a game designer.

It wasn't until he bought an Apple II in college that he became interested in programming, but his desire wasn't to program games, but to control the robots he wanted to design. He taught himself how to program over a year and a half, and it was only later, when he started buying games from a store in New York, that he became hooked on "these little worlds that exist inside the computer." Eventually, his interest in robots was put to one side, and he became fascinated by the potential of artificial intelligence and simulations.

Raid on Bungeling Bay

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Wright came to the conclusion that he could probably write one of these games for himself, but rather than compete with Apple II programmers who were, by that point, experts with the machine, he decided to level the playing field. He bought a brand new machine - the Commodore 64 - and spent two months learning everything about it. When he was done, he deisgned Raid on Bungeling Bay , his first published game. At this point, footage of the game plays on a big screen in the conference hall. As it starts, Wright says, "I warn you, it's stupid." He's kind of consistently down on it through the rest of the talk.

For those who haven't seen it, it's a simple enough game: the player controls a helicopter, and the objective is to destroy warehouses littered around a city. But Wright explains that there's more going on. "Underneath this game, to entertain myself, I wrote this elaborate simulation of ships and factories and supply routes."

You blow up the factories, but as you're doing so, planes start to attack, and the factories become stronger and harder to blow up. Understanding the simulation that was driving this progression could make you better at the game, but almost no player would notice that stuff was there. To the gamer, it was just a simple game about blowing up buildings.

Bungeling Bay was a big success, apparently selling 800,000 units in Japan alone, but it's the next part of the story that's famous. Wright realised that he had more fun designing cities in the level editor he'd built for Raid on Bungeling Bay than he did blowing them up in the game afterwards.

SimCity

From there, the idea for SimCity was born, and development for the game also birthed Wright's interest in using games as educational software. As he read a lot about urban planning, when he'd learn a new concept, he'd go try to program it. "That took what was a dry, academic subject and made it fascinating."

The part of the story that I didn't know was that the second big inspiration on SimCity - and on all of Wright's games, really - is a science-fiction story called "The 7th Sally" by Stanislaw Lem , the Polish author of Solaris and much more. The story is about two competing robot inventors, Trurl and Klapaucius. Trurl finds an exiled dictator on an asteroid and, as a gift, designs him a glass box inside which sits a new, simulated civilization to rule over.

Klapaucius sees his friend as vain and mad, and the story explores the inevitable ethical question of, you know, creating life and giving control over it to a madman. From the story:

"Prove to me here and now, once and for all, that they do not feel, that they do not think, that they do not in any way exist as being conscious of their enclosure between the two abysses of oblivion - the abyss before birth and the abyss that follows death - prove this to me, Trurl, and I'll leave you be! Prove that you only imitated suffering, and did not create it!"

Which is something to think about, the next time you're making a little person wet himself and catch on fire in The Sims.

Wright only ever thought SimCity would have niche appeal for architects and strategy gamers. As it turned out, it was the first computer game ever reviewed by TIME magazine, brought a more adult audience to games, and received a lot of mainstream press coverage because, Wright says, the game ran on Macintosh, a machine that journalists owned.

SimAnt, SimCopter

SimCity was huge, and spawned half a dozen other games with the "Sim" prefix. SimAnt was one. Wright says that he "wanted to convince adults why ants were cool," but he didn't think that worked out. Instead, the core audience for the game was twelve-year-old boys, "who already knew that ants were cool."

Next came SimLife , SimFarm and eventually SimCopter , a simple flight simulator in which you could fly around the cities you'd built in SimCity. It used a lot of the same simulation: fires would break out, traffic would mount dynamically, but it would use those problems as prompts for linear missions. You would use your helicopter to put out the fires by dumping water on them, or to clear the traffic by reporting on it.

"What GTA grew into, this is what SimCopter was supposed to be," says Wright. Th game had fake radio stations. You could get out the copter and walk around, etc. But they never had the team or budget to continue the series.

As Wright talks through each game from his past, he also explains where the obsession that inspired it came from. At first, he says he struggles to explain his obsession with helicopters. "Helicopters are just cool, you know. They're just cool."

But he then talks for the next five minutes about Igor Sikorsky, the invention of the helicopter, and the problems of gyroscopic procession. If you've played one of his games, you get a sense of the mind at work behind them, and Wright doesn't disappoint when you hear him talk in person. He is deeply knowledgeable about a dozen different subjects, and can talk eloquently about each.

The Sims

The next video that rolls on the screen is considerably longer than the others, running through each of The Sims games and their numerous expansion packs. I had forgotten just how bizarre and varied some of them were. Like, there was an entire magic-themed expansion pack for the first game, in case what you really wanted from your simulated people was top hats and card tricks.

"SimAnt was probably the biggest inspiration on The Sims," explains Wright. That game taught Wright the concept of distributed intelligence; where a single ant is stupid, but "an ant colony has about the intelligence level of a dog, in terms of problem solving." Remember, adults: ants are cool.

Essentially, this is the idea that complex behaviour can spawn from very simple rules. In practice, the intelligence of the little people in The Sims doesn't exist in the sims themselves, but in the items of their environment: the coffee machine told the sims how to use it. Put another way, "As you added expansion packs, The Sims got smarter," says Wright. Which is a powerful argument for why you should have wanted top hats and card tricks in your copy of The Sims.

Wright goes on to cite the books of Chistopher Alexander, the architect and designer, as another influence on The Sims. Alexander wrote books about how the intention of our designed environment was to shape human interaction. "He's a sort of anti-architect, and writes about privacy, socialising backyards; where to put a bench."

The Sims became Wright's most successful game, and the series as a whole has sold well over 100 million copies on PC. But it almost didn't happen. When Maxis first started kicking around ideas for the game, which Wright was called "Doll's House" at the time, they brought in a focus group and presented the concept alongside four other potential games. The entire focus group hated the Doll's House concept, but liked the other three. Wright made the one they hated.

Wright on indie games, the future of consoles, and his next game

At this point, questions are opened up to the audience. In the ensuing answers, Wright touches on the future of film and television, his work at his latest startup, the Stupid Fun Club, and the TV show he created Bar Karma . But while talking about hard science-fiction and the books that have influenced him, he mentions just briefly that "one of the game projects" he's working on right now is directly inspired by a story by science-fiction author Bruce Sterling. Whether that project ever sees the light of day is anyone's guess, though.

In the last ten minutes, Wright runs down a list of interesting thoughts. On the future of gaming: "I think the games industry is moving towards a much more healthy space than it was in five years ago." "I think the old model where we have a console generation every five or six years is obviously dead." "We'll still have consoles, but tablets and smartphones and Facebook change our reliance on them and more changes are inevitable."

On indie games: "We used to think of the indie space as the up and coming developers, young designers just out of school. Now, some of the most experienced developers I know are moving into the indie space." "Traditional business models are breaking down and indie devs are making real money."

On the artistic expression in games: "I've always thought of art as one of the most useless terms in the world."

On the malleability of games: "Movies are a one size fits all experience, but games are really malleable and we're just learning to turn those knobs. You and I might start playing the game, but two months later our games look entirely different, because yours has evolved to fit and entertain you and mine has evolved to fit and entertain me." He has a one-year-old son who is already using an iPad, and already thinks he should be able to touch and drag things around on his television. "He looks at us like it's broken."

On accessibility versus depth: "It's not that [gamer's] attention spans are shorter, it's that they're playing games interstitially now." "The rise of interstitial games, where people are playing games in the cracks of their lives. It's the difference between a movie and YouTube; there is no [gaming equivalent of] television in between." "The kind of games I like to do are open sandbox games. There are metrics of progression, but it's not mission based." "It's kind of refreshing to do an entire game project in the course of a year. You're still going to have these long epics, but it's rewarding for the designer to make these shorter games."

On games as education tools: "Games are motivating kids far more thoroughly - whether they're learning Pokemon statistics or whatever - than teachers. Which is a shame."

And with that, he's done, and everyone files outside. Expect the full video of the event to appear online in the coming days or weeks.