Welcome to The Zero: the making of Kentucky Route Zero's open road

Cracking the highway code.

Like Rapture is to BioShock, Los Santos is to Grand Theft Auto 5, and the Greenbriar residence is to Gone Home, The Zero—the mysterious highway that binds Kentucky Route Zero together—is as big a star as any one of the game's cast of dysfunctional characters. Sneaking us into bygone America—an era of neon signs, roadside diners and lazy rivers—The Zero's hazy, two-dimensional monochromatic design contrasts with KRZ's highly stylised 3D character models, animations and story settings. Few games have captured the imagination, inexhaustible possibility and spirit of the open road with similar style and conviction.

"I started off saying and thinking I wanted to downplay the roles of the setting but I guess it's true: the place is really important to me," says the game's co-creator Jake Elliott. Before moving to Kentucky himself, Elliott often travelled to the Bluegrass State to visit his wife's relatives. En route he'd wonder at the journey's contradictory landscapes and environments, and the vastness of both its surface and cavernous highways within Mammoth Cave—the world's largest known cave system.

This varied geography inspired much of The Zero's superficial details. In Kentucky singular wide-berthing roads are all that all that splits the land from the sky. "If I go out into the highway that's closest to me, it's a really strange feeling," Elliott adds. "Places like this, where there's no hills, it feels like there's way too much sky. It's really hard to adjust to and feels like you could just fall into it, it's really strange."

This sense of overwrought scale was consistent with The Zero's earliest designs, and while Elliot and co-creator Tamas Kemenczy didn't know exactly what the map would look like in its final form, or how it would operate mechanically, it was to play a central role from the outset.

"I thought a lot of the game would happen on The Zero," co-creator Tamas Kemenczy admits. "I thought the way that we were designing The Zero was that, after the first act, everything would be on The Zero for a long period of time. Then it sort of got remodelled so that the characters were interweaving in and out of The Zero throughout the acts. That was an interesting development a little later on that was not clearly defined from the get go."

It wasn't until Elliot and Kemenczy began digging into KRZ's second act that The Zero started taking shape. I'm reminded of Mulholland Drive when Elliot speaks of mirroring Lynchian-esque locales which pull upon the psychological and emotional tendencies of the viewer—depicting spaces which aren't always rational or physical.

Beyond doffs of the cap to a number of American playwrights such as Eugene O'Neil, Arthur Miller, and Tennessee Williams, KRZ has a magical realism quality about it, not least out on The Zero, where psychological spaces are projected into a physical reality. Earlier iterations weighed heavier on exploration using the combination lock-like mechanic that features in later acts. While the map wasn't always intended to be a fully-formed circle, once this idea was suggested Elliot and Kemenczy decided it made perfect sense.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The very first approach we had to driving at all was that it was going to be that you were sitting in the car and it was realistic and you could see the truck.

"The very first approach we had to driving at all was that it was going to be that you were sitting in the car and it was realistic and you could see the truck. That's what we were thinking going into development," Elliott explains. "It didn't really work well in the way we'd have liked so we did this abstract map mode, and then we didn't know how that'd apply to being on The Zero. I remember there was a version of it where it was just like the above ground map but it was almost like it was made up of a bunch of jigsaw pieces that would kind of get reassembled randomly.

"The road was different every time you went on it, it extended infinitely and the only way you could navigate it was by following these kind of ritualistic directions—like take three lefts and then a right, or something."

Kemenczy interjects: "Which we kept ultimately, but the ritualistic driving was more about these symbols, and even the way you get back onto The Zero doesn't depict mechanical directions."

Further to its design, another intriguing quirk of Kentucky Route Zero's open road is its sense of permanence. Optional locations litter the map's roadside which, once visited, grant players access to additional story vignettes that often bolster elements of the main plotline. What's interesting, though, is that once these locations have been inspected they vanish from the map. Much similar to how the game's dialogue system functions, the conversations had in these areas are spent and therefore inaccessible thereafter.

"It's a kind of realism that makes the people feel a bit more real—that you can't just go and treat them like an information vending machine or something like that," says Elliot of the process. This in turn prevents players from interrogating NPCs and repeating themselves—a mechanic which has plagued narrative-driven games for decades.

Kentucky Route Zero is good at elegant, restrained storytelling. In an interview with Rock, Paper, Shotgun last year, Elliott praised From Software's Dark Souls for being "economical with the way it uses lore", which is something I'm compelled to acknowledge as I feel there are some strangely appropriate, albeit wholly incongruous, parallels to be drawn between KRZ and Lordran. Elliot laughs at the general comparison, but does recognise the abstract likeness as far as each game's wider world and the player's insignificance within it is concerned.

"Lordran and the settings for the other Dark Souls games have a lot of history there but you really have to dig for it. When you play it, you're just dropped in and asked to understand and accept and just respond to the way all of these creatures are behaving and how these environments work etc.," says Elliott. "The characters that actually will talk to you talk to you often with this sense of pity, they know what's going on but they know you're new to this. In KRZ also we don't ask the player to bone up on a bunch of lore before we start talking to them—we just start talking to them as though they're already an inhabitant of the world.

"That's something we get from magical realist fiction where one of the technical tenets of that genre is that people accept the magical and the bizarre along with the real."

Of course visually, these games couldn't be more at odds with one another and although KRZ suits its universally dull and muted colour palette, The Zero itself is almost mesmerizing in its use of laborious two-tone that distances itself from even the darkest of the game's narrative scenes.

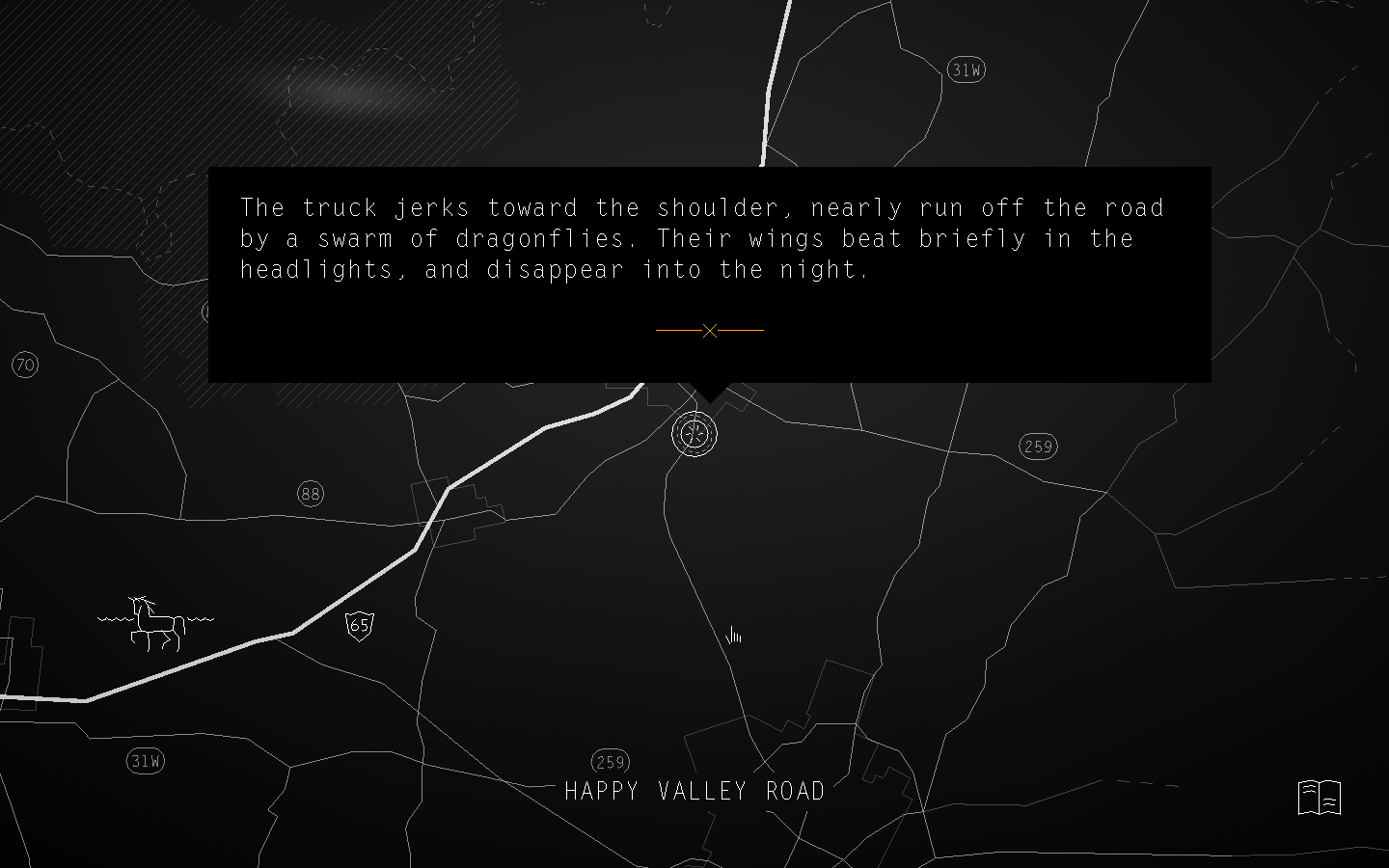

"The map mode is loosely inspired by early computer graphics that had all sorts of limitations and where it was pretty common to just have simple line art. One example is Mystery House but even earlier video art stuff like the Rutt/Etra system which is a video synthesiser that works with scan lines and has a certain look to it, like a rippling wave-form. Specifically The Zero has ripples and this sort of ribbed appearance reminiscent of the uniform appearance of scan lines."

"I think in some other games when they show a map they have a scale morphism or metaphor, maybe like a highway or something," Elliott adds. "I think in Sam and Max Hit the Road, they have a touristy cheesy highway map—there's other metaphors for what a map is—and I think ours is a weird non-time specific early computer influence. We're topological too because it's kind of like a graphic map that has topological too. The aesthetic has a pretty fair connection to that sort of stuff."

We didn't want players to disable the effect unless they were really bothered by the crackling, so we gave it the unappealing label 'disable artisanal audio' in the menu.

Likewise, KRZ's sound has a similarly strong connection to the The Zero—such as the humming engine of Conway's truck which pitches up and down depending on the speed you're travelling. In Act 2 alone the map has six different loops which switch whenever the player turns at certain symbols, alternating to different 'tracks' as it were in the process. It may sound straightforward, but this process is so computationally intensive that it's actually broken some players' computers.

"Since the Zero is a dark, subterranean cave highway, we thought it should have an ever-changing sense of space," says KRZ's sound designer Ben Babbitt. "So as the walls of the cave expand and contract around you, some properties of a dynamic reverb effect are modulated by the tunnel diameter immediately around the truck. So some parts of the cave have the sense of being more muddy, resonant or close, etc., by the way the reverb affects the music and engine sound in different spots.

"Real-time modulation of the reverb effect worked pretty well on all the computers we tested the game with at the time, but after we published Act II we discovered that it was too resource-intensive for some players' computers—it makes a weird, distorted crackling sound. That bothered some people, so for them we added an option to disable the reverb effect along the Zero. But we didn't want players to disable the effect unless they were really bothered by the crackling, so we gave it the unappealing label 'disable artisanal audio' in the menu."

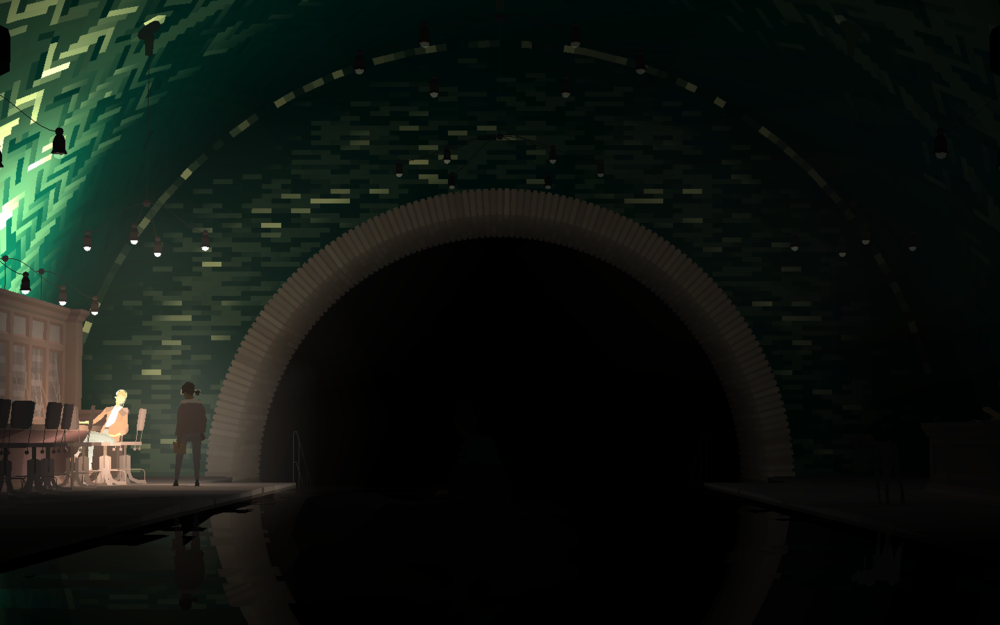

Act 4's transition from The Zero into the river-set Echo, while seemingly jarring in game terms—suddenly the player is ostensibly a passenger and observer of the game's ever-growing cast—was an organic process behind the scenes. The decision to move the action onto the water was made early on in KRZ's development and recaptured the aforementioned jigsaw puzzle layout that was originally designed for The Zero. Filled with people living peaceful and sedentary lives along its riverbanks, The Echo feels less sinister against its land-bound counterpart—which is a direct result of Elliot and Kemenczy's desire to portray something a little warmer and more human.

As such, Act 4 is almost certainly the calm before the fifth and final act's storm where I suspect we'll spend much of our time travelling The Zero once more. Both Elliot and Kemenczy remain tight-lipped—"We got a good outline going, an interlude and right now we're doing a lot of housekeeping, getting our codebase up to date on Unity 5," says Kemenczy—however where Kentucky Route Zero's largely maladjusted characters falter within its delicate and malleable world, The Zero remains a rare constant.