What it's like to have the fastest internet in the country

Tearing up my neighborhood in the name of speed.

Running the fiber

After four days of noise, debris, and machinery, the conduit was complete and everything patched up. Unfortunately, the ground surgery left patches of black asphalt in a previously unmarked road around my block. But it didn't matter. Because fiber.

Another company responsible for the actual fiber came out to run the cable. The cable comes on a large spool and is pulled by hand through the conduit, though on longer runs a machine is used to run the fiber. Since the conduit was fresh and the length was less than a mile away from a main trunk, it was easy. I found out later on that the actual glass core in the fiber line is manufactured by Corning—the same company that makes Gorilla Glass.

I needed a piping run along the side of my house to protect the fiber cable. Traditionally, an optical network terminal (ONT) box would be installed on the outside of the premise, allowing the primary line to terminate in the box, and then another smaller fiber cable would run into the house. In my case, I just had the line run straight into my office.

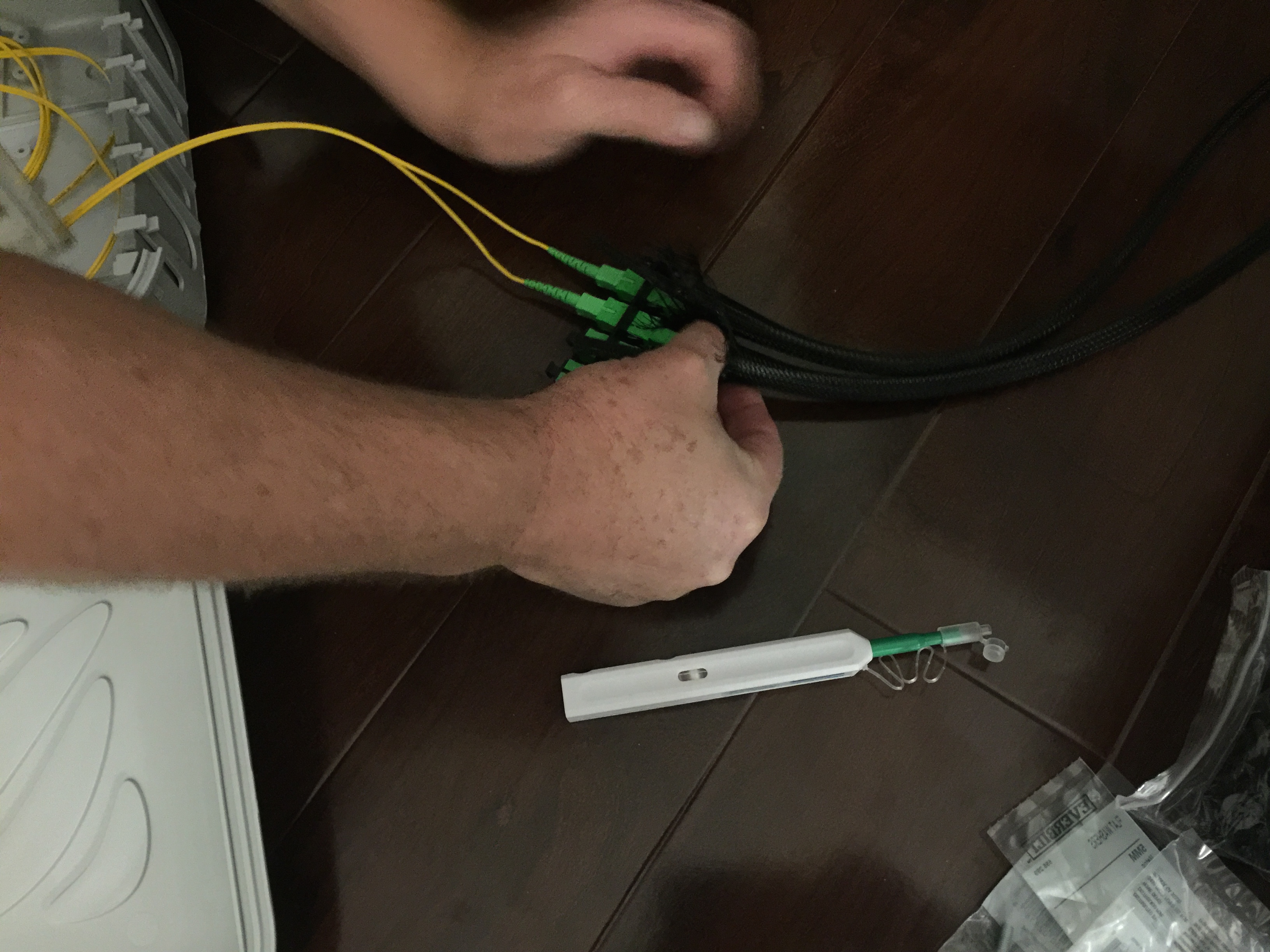

Once inside, the fiber cable ends in an SC-APC optical connector. There are actually two lines that run into the house, one for upstream and the other for downstream.

After the fiber team finished running the lines into my home office, the splicing team came. The team's responsibility was to connect all the appropriate lines together. Thankfully, most of the fiber lines outside the house had connectors pre-installed from the factory, which made things go much faster. For the house, they needed to do more.

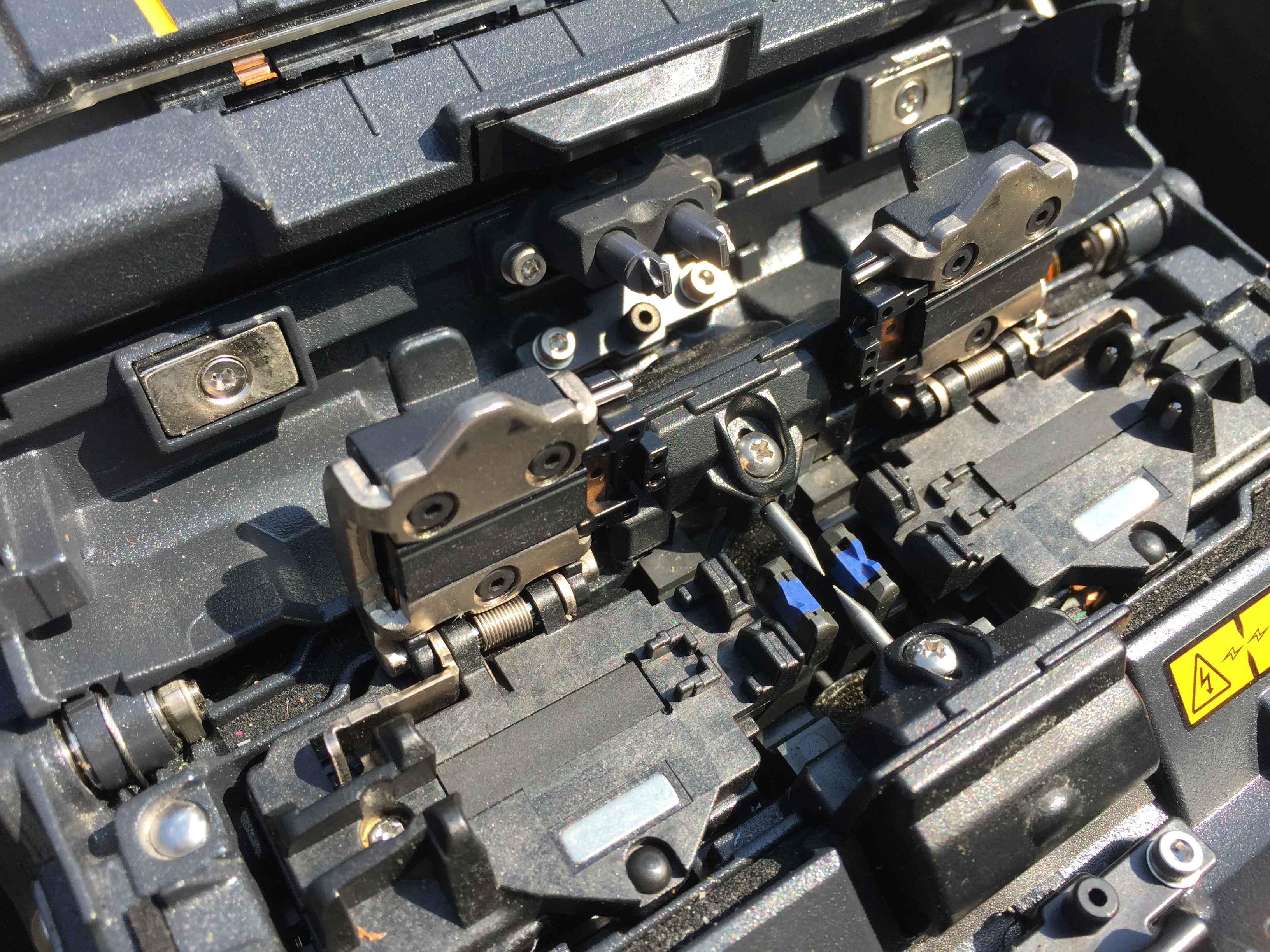

Utilizing a device called a fusion arc splicer, two fibers are literally fused together by electrical plasma. The fusion splicer optically aligns the two fibers while you watch on an LCD screen. Once aligned, an arc is emitted, and the two fibers become one. The splicer then gives a reading on the expected signal loss, with 0.00dB being a perfect bond. There's a maximum threshold allowed and if the fuse is poor, they repeat the whole procedure. The splice point is then protected using a shield that's heated and bonded to the fiber.

After the splicing team finished their job, the installation team came out several days later. There aren't any consumer routers and switches on the market that support 2Gps speeds, as everything tops out at one gigabit. The Ethernet ports on your motherboard, the router you're using, and the Wi-Fi access point you might have are all 1Gbps.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

To get the speeds I wanted, Comcast supplied a Juniper Networks ACX2100 enterprise 1U router, which had to be installed on a rack. The ACX2100 is actually used by Comcast for its own equipment and isn't normally deployed as customer premise equipment (CPE). The installation team of three that came out to finalize the setup told me that they had never seen one of these used at a customer's location, let alone a person's house. Want to buy your own ACX1200? They only cost around $10,000. Insane.

At this point, the construction and installation was done, and the rest was up to me. I did a quick calculation on how much Comcast spent on bringing fiber to an unassuming house in a relatively quiet neighborhood of San Jose. Based on an average cost per head of $50/hour for the crew, all the equipment, and total days spent, it would take Comcast around a decade to break even on its investment on me. I tried asking Comcast if this was actually the case, but was told the cost was confidential. It did say it wouldn't take as long as I had estimated.

The final steps

You can't connect directly to the Juniper at full speed if you don't have a 10Gbps Ethernet card with SFP+ ports—RJ45 copper connections are so last year. Luckily, my entire house is wired and already running on 10G, and I have a 10G switch in place that has SFP+ ports. All I needed was a router/firewall to support all of this, and as I mentioned earlier, there are no consumer products with 10Gbps support.

Luckily, Netgate, the maker of my pfSense firewall appliance has a solution that isn't the typical $5000 to $9000 you normally see for a 10G enterprise Cisco router. The problem was my existing Netgate pfSense SG-2440 box is only a 1Gbps box. I needed something that could handle the new 2Gbps speeds.

Enter the Netgate XG-1541. Configured with a 2-port Chelsio T520 10G card, it was the perfect solution. Coming in at $2848, it's still out of reach for many, but so is a 2Gbps metro fiber connection.

The key to the XG-1541 is being able to handle higher than 1Gbps per port. By default the XG-1541 already has two Intel 10G ports on it, but they're copper ports. I needed support for two SFP+ fiber ports since the Juniper equipment supplied uses multi-mode fiber. Thus, the Chelsio SFP+ card was added.

SFP+ ports support pluggable transceivers of varying types: copper, single-mode, and multi-mode laser, and Twinax direct-attached-copper cables. Since Comcast had supplied a single multi-mode optical transceiver, that's what I had to use.

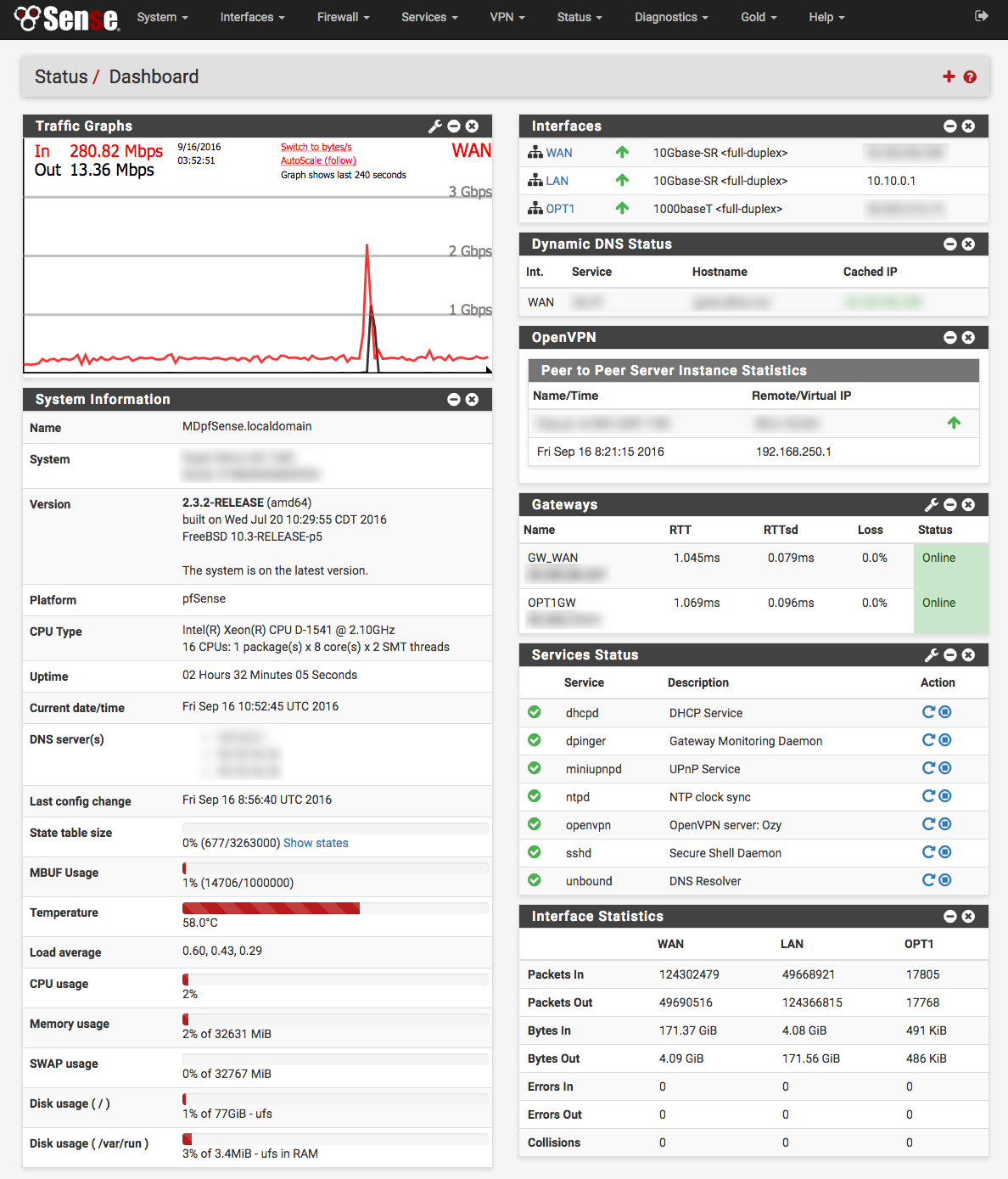

Why pfSense? I basically went with the best firewall software on the market. Even better, it's free and you can easily build a pfSense firewall yourself with some spare parts. pfSense is leaps and bounds better than any router/firewall in a box that you can buy.

The feature list to pfSense is long and detailed, and supports many things you won't find on consumer-grade routers. This isn't a knock at consumer routers, it's just that pfSense will give you total control over your network if that's what you're looking for. You can also add functionality to your pfSense box via community addons, which are vetted by the pfSense team.

The learning curve is steep, but if you're willing you can do some very sophisticated things. Me, I prefer learning about and controlling the ins and outs of what's going on in my network. If you don't need 10Gbps and don't have the parts to build your own pfSense firewall/router, Netgate's smaller units work really well and consume very little power; around 7 watts in most cases.

Netgate sent the following monster configuration for its XG-1541:

- CPU: Intel Xeon D-1541 8-core 2.1GHz

- RAM: 16GB DDR4 UDIMM

- SSD: Intel 535 Series 120GB M.2 SSD

- Network: 2x Intel i350-AM2 1Gbps ports

- Network: 2x 10GBASE-T 10Gbps copper ports

- Network: Chelsio T-520-SO-CR 2-port 10Gbps SFP+ expansion

- Dedicated IMPI port, Serial port, VGA port, BMC

In case there's any confusion, this is one monster of a firewall. The XG-1541 can easily handle eight million active connections. Netgate is packing quite a bit of punch in the XG-1541. The unit's got more horse power than most people's PCs, and the company's inclusion of an Intel 535 Series SSD is a welcome addition.

Being a 1U box meant for racks, the XG-1541 can get a little loud, so it's not suitable for a home office or bedroom out of the box. The CPU fan spins at 15,000rpm at full bore, so if you'd like, you can swap it out for something a tad slower and quieter, which is what I did.

Configuring pfSense to act as my router and firewall and play nice with the Juniper was easy. Comcast actually calls this service metro Ethernet, as it's technically a fully dedicated line. The bandwidth is guaranteed and there are no caps. I was given a dedicated IP address for the 2Gbps service. Here's the crazy thing: one of the 1Gbps copper ports on the Juniper box is provisioned to supply a full 1Gbps (up and down) line, independent of the 2Gbps service. So essentially, I have a dedicated two gigabit line and a dedicated one gigabit line.

Thankfully, the Netgate XG-1541 can take both lines. Using pfSense, I was able to set the gigabit line as a fail-over option. I also configured an OpenVPN server on that line so I could tunnel directly into work without consuming any bandwidth from the 2Gbps line.

I had now solved the firewall/router problem for speeds greater than 1Gbps. Only one problem remained: how to get the six other 10Gbps devices in my network to take advantage of the 2Gbps service. I needed a 10G switch.

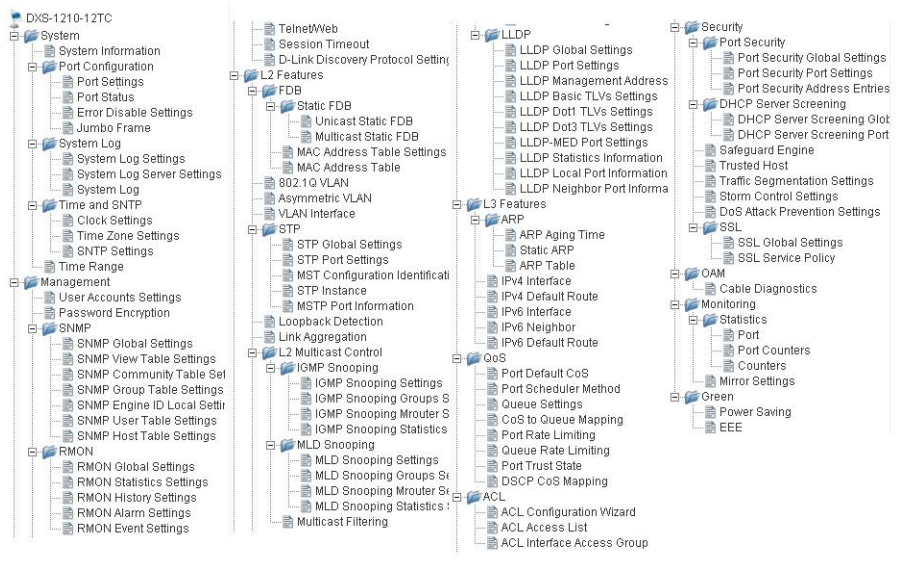

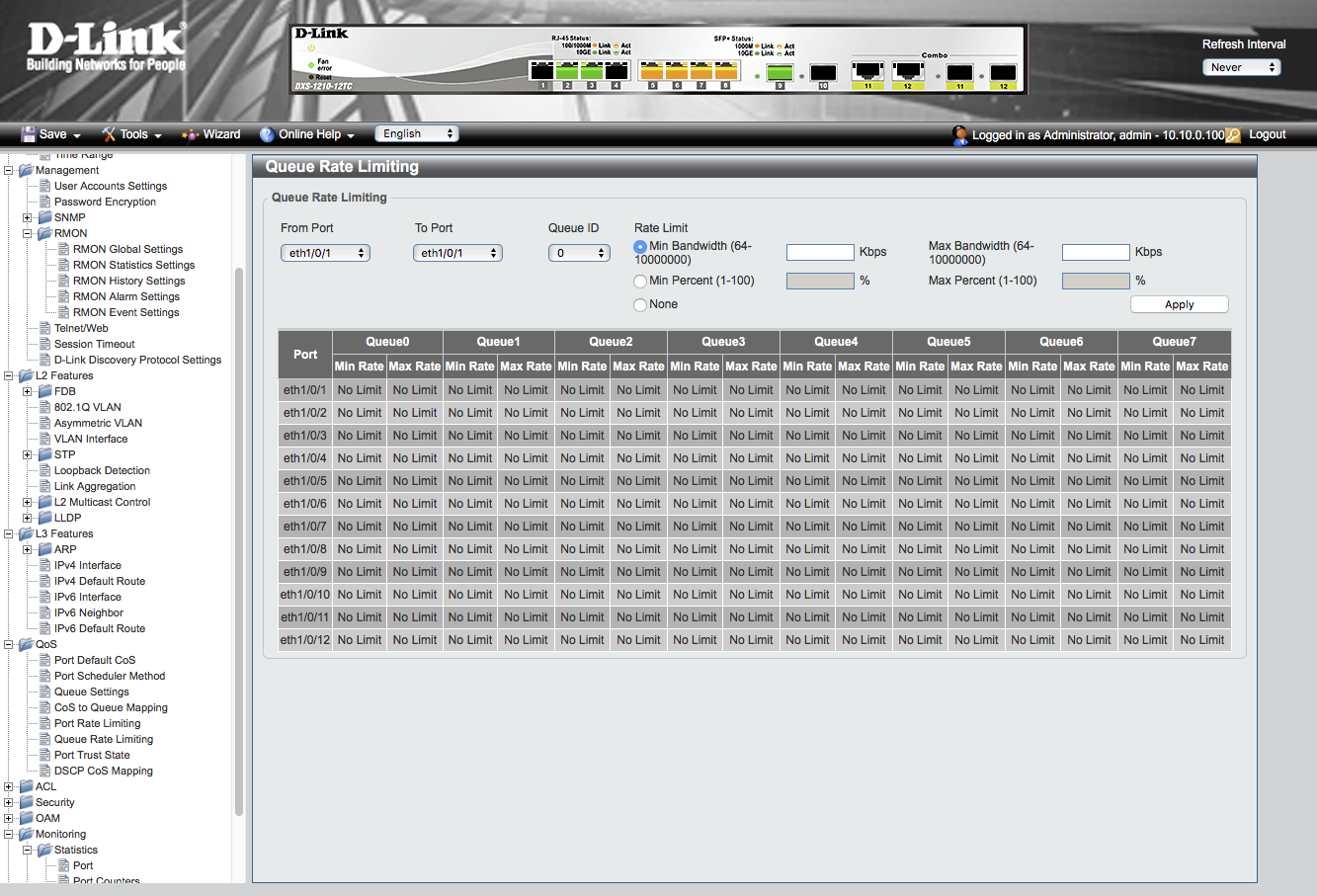

D-Link DXS-1210-12TC

The D-Link DXS-1210 is one of the more affordable 10G switches, and when I say 'affordable,' I mean it's not several thousands of dollars. It's still a $1500 switch at the end of the day, but hey, 10 gigabits!

D-Link did a great job building the DXS. It takes up very little room as far as a 1U rackable unit goes and is quiet enough to use in a home environment. You'll typically find rack equipment with 15,000rpm cooling fans, and while the DXS can ramp up to those speeds, in only does so during bootup or at near full loads. In my use, I haven't ever heard the unit's jet engines take off.

The DXS-1210-12TC is a Layer 2 switch, meaning it's hardware-based and has dedicated processors designed for routing purposes. This allows for faster performance and lower latency across the board. Layer 2 switches also route based on MAC addresses rather than IP addresses. Some notables specs:

• 8 x 10GBASE-T copper ports

• 2 x 10G SFP+ optical ports

• 2 x 10GBASE-T/SFP+ combo ports

Switching Capacity

• 240Gbps

Network Cables for 10GBASE-T

• CAT-6 (30m max)

• CAT-6A or CAT-7 (100m max)

That's a full 12 ports of dedicated 10G bandwidth on each port. The last two ports are combo RJ45/SFP+ ports, meaning you can use either RJ45 copper or SFP+ but not both at the same time. A switch like the DXS-1210-12TC is useful for someone who wants to use existing copper cables. CAT5a will work but CAT6 and greater is recommended for 10G speeds.

But aside from hardware specifics, the DXS-1210-12TC is chock full of management features not seen in other switches at this price range. VLANs in particular are useful, especially due to the way Comcast provisions its fiber service. The DXS-12010-12TC is able to properly manage both the 2Gbps and 1Gbps service independently of each other. I didn't set it up to work that way, but some might find it useful.

D-Link provides several ways of managing the DXS-1210-12TC, but I used the web management method. You're able to manage all aspects of the switch's functions, including features such as link aggregation where ports are combined for higher throughput, VLANs, QoS, CoS, and many other packet management features. I did a quick test between two 10G NAS units and saw sustained transfer speeds of 994 MB/sec through the switch. (The storage speed was the bottleneck.)

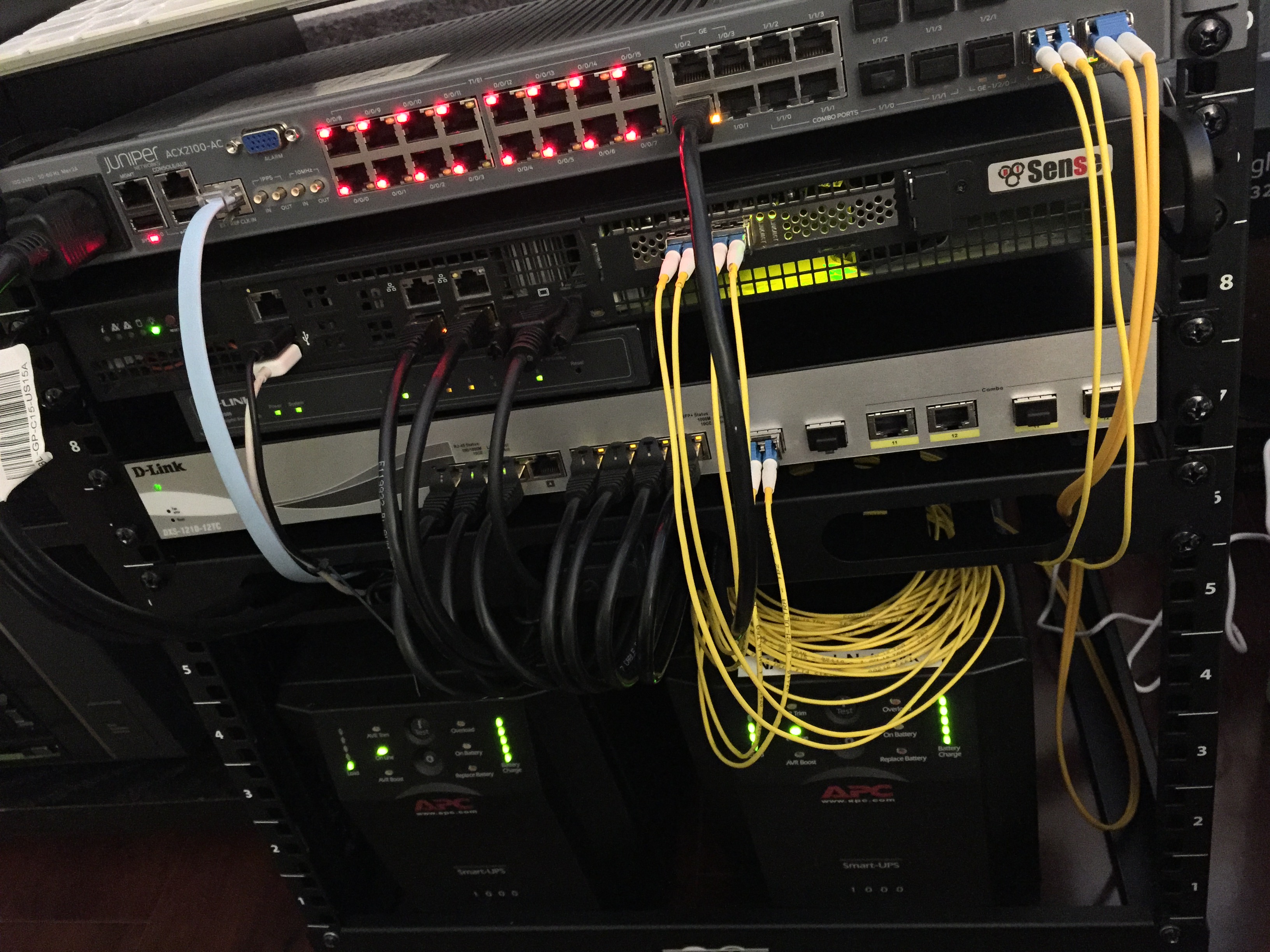

After everything was mounted and wired up, I was ready go to. The topology goes like this: Juniper ACX1200 router -> Netgate XG1541 -> D-Link DXS-1210-12TC -> clients. Here's how it all looks:

Every part of my equipment stack is backed up by battery.

You might be thinking "that photo above looks unwieldy, I don't want that in my room," and I wouldn't blame you. Typically, Comcast will request an area in your house—preferably the garage or some other place—to install a rack directly onto the wall for the Juniper. I prefer having everything within arms reach of where I work.

The white box to the right of the rack is the jumper box, where the thicker armored fiber comes in from the outside and switches over to a less rugged line. Due to the sensitivity of the jump point, it's placed inside this box. Typically, a box like this would exist outside of the house or building and be referred to as an ONT, or optical network terminal. The jump point look likes this: