The futile search for a single message in Far Cry 5

Far Cry 5 is tonally confused, but it has a lot to say in isolation.

After a number of huge games and reinventions, Far Cry has accumulated an absurd amount of thematic obligations. Emotional sincerity and nuance sit right next to Grand Theft Auto-style 'satire' and unapologetic violence. New entries need to include brutality to the point of repulsion, have some sort of philosophical or subversive layer, and offer breathtakingly beautiful virtual tourism, all at the same time. This mix isn’t just contradictory—it’s impossible to truly pay off without choosing an element to emphasize.

This is why I believe that accusations that Far Cry 5 doesn’t have anything to say, or that it refuses to take a stance on the many subjects it approaches in its over-the-top tale of reclaiming Americana in rural Montana, are false. It just says these things in individual pieces, each beholden to a different portion of what has become an inherently conflicted series.

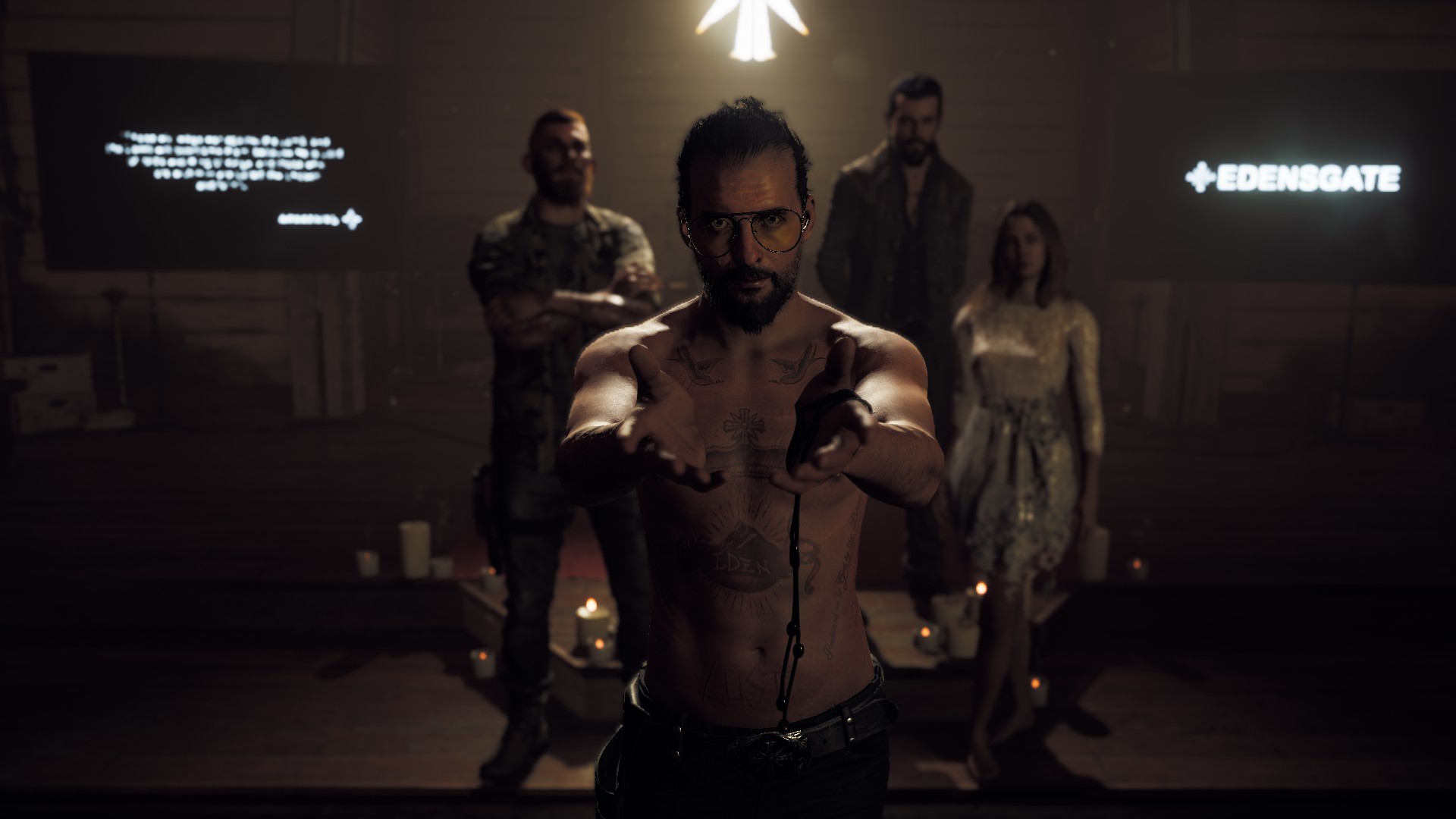

In Far Cry 5, a pseudo-Christian group known as the Project at Eden’s Gate established itself in a small, struggling, isolated segment of rural Montana, and preached about a coming end: The Collapse. This is an inevitable event where the economic and political elite would destroy themselves and the world in the process, leaving only the faithful alive. The damaged and economically disadvantaged flocked to this message, with its promise of salvation and a turning of the tables to come, to the point that the so-called “Peggies” became the de facto power of the region. The now dominant religion is headed by four figures. The Father, Joseph Seed, and his ‘Family’ of three lieutenants, each helping to control the members of the cult with a unique philosophy and methodology.

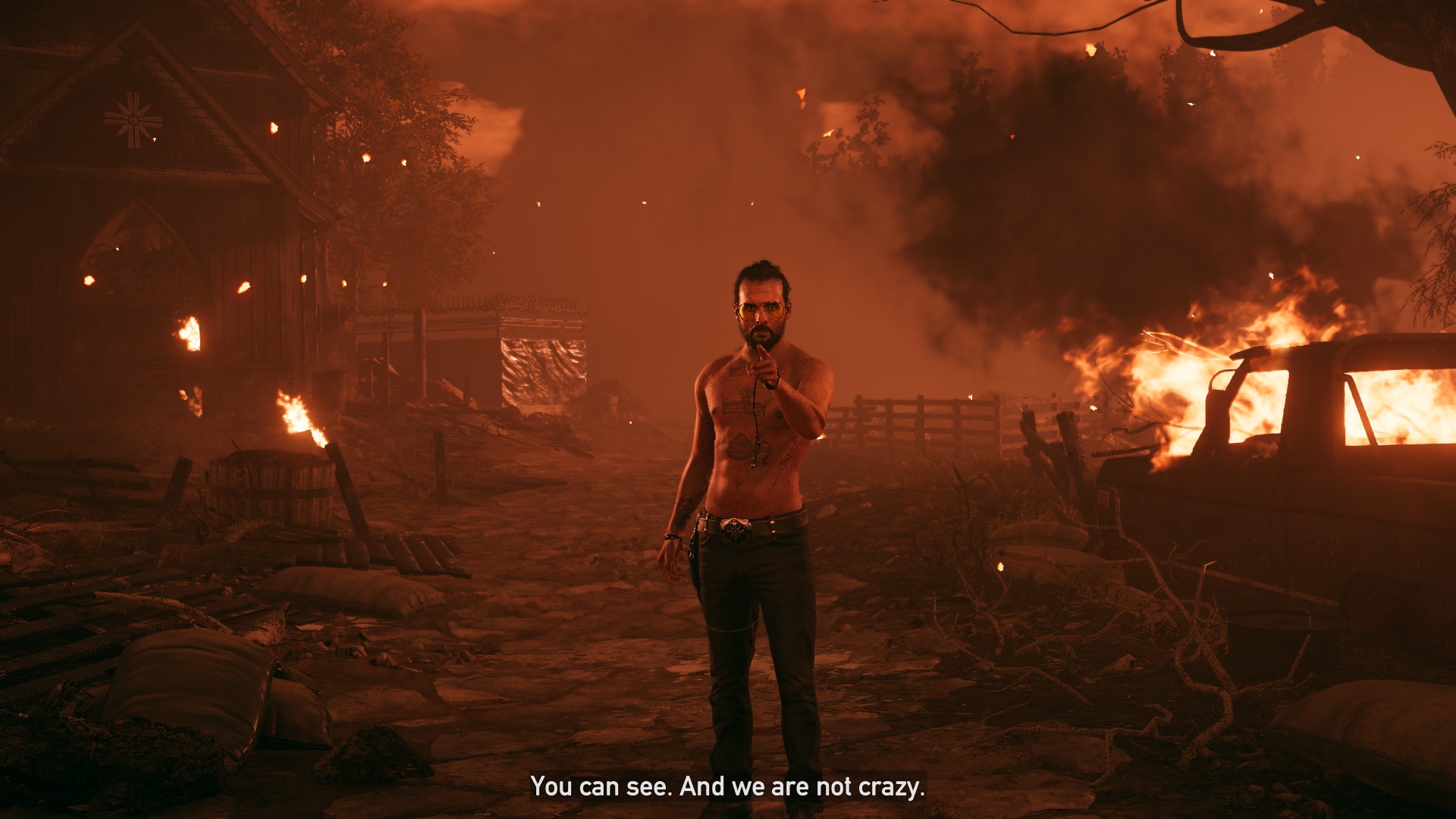

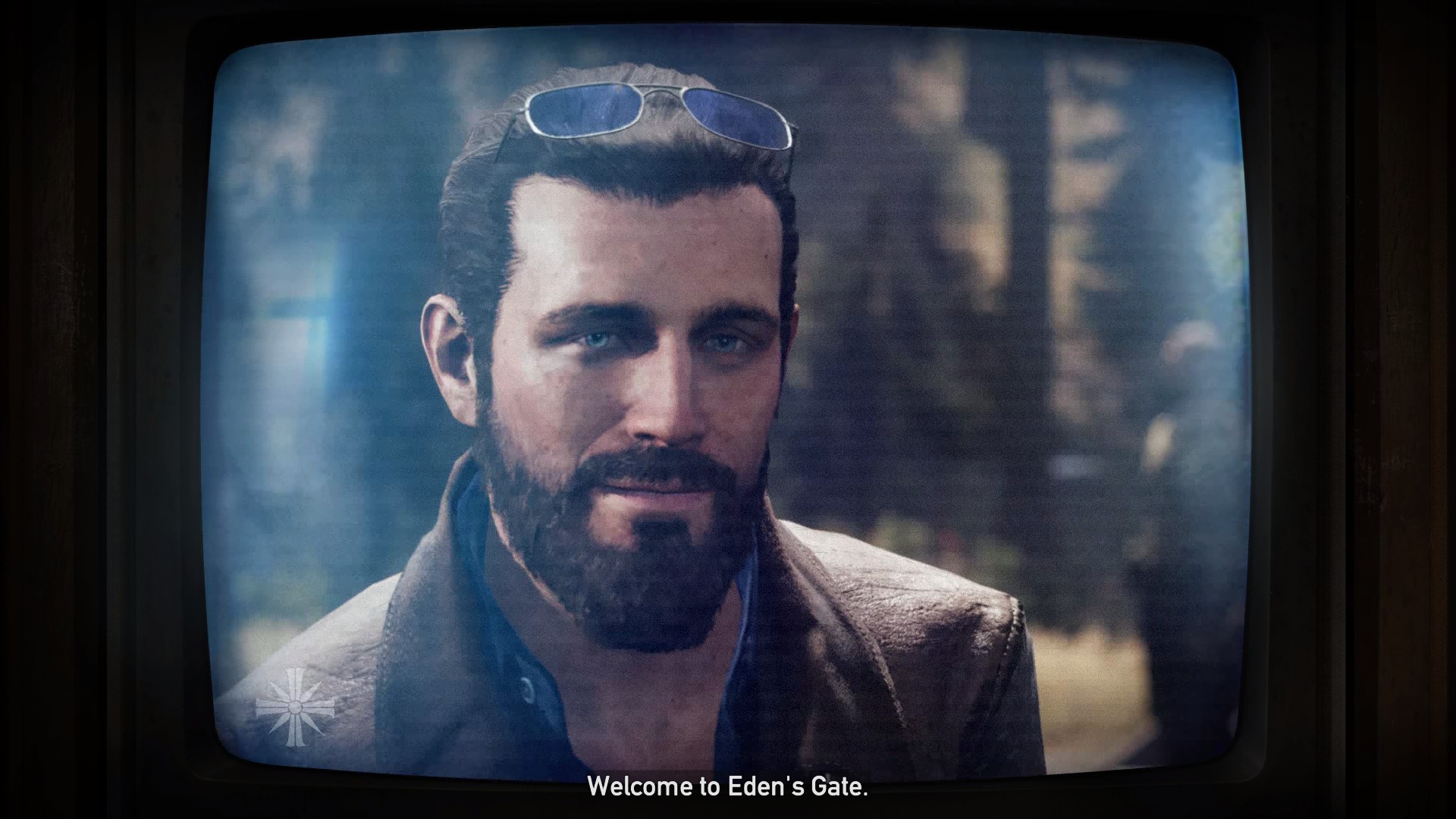

Joseph Seed, with his tinted sunglasses, preaches words that are alternately welcoming, reasoning, and vengeful. Faith Seed is the manipulator of the group, claiming innocence while dancing through hallucinogenic fields of a mind-altering drug she manufactures called Bliss in a lacy white dress. Military veteran Jacob Seed sees the world in shades of nihilism, brainwashing the player character to react to the trigger of the song ‘Only You’ by The Platters and monologuing about the need to cull the herd of humanity of weakness. Finally, John Seed spouts self help-adjacent phrases behind a brilliant smile and baby blue eyes, but harbors a sadistic need to carve the names of sins into one’s flesh and tear the skin off in strips to absolve the person of sin.

The charismatic leader, the seeming innocent, the grizzled soldier, and the not-so-undercover sadist. As caricatures with nothing more to do than misuse portions of Christian scripture to sound extremely creepy (and therefore being suitable targets in the eyes of the player), these figures could be effective enough. Far Cry 5, however, does feel the need to say something—to be more than a romp against cartoonish villains in the Midwestern United States. It attempts to give these characters nuance, in portions, and so undermines itself in an approach that is increasingly revealed to be typical of the game.

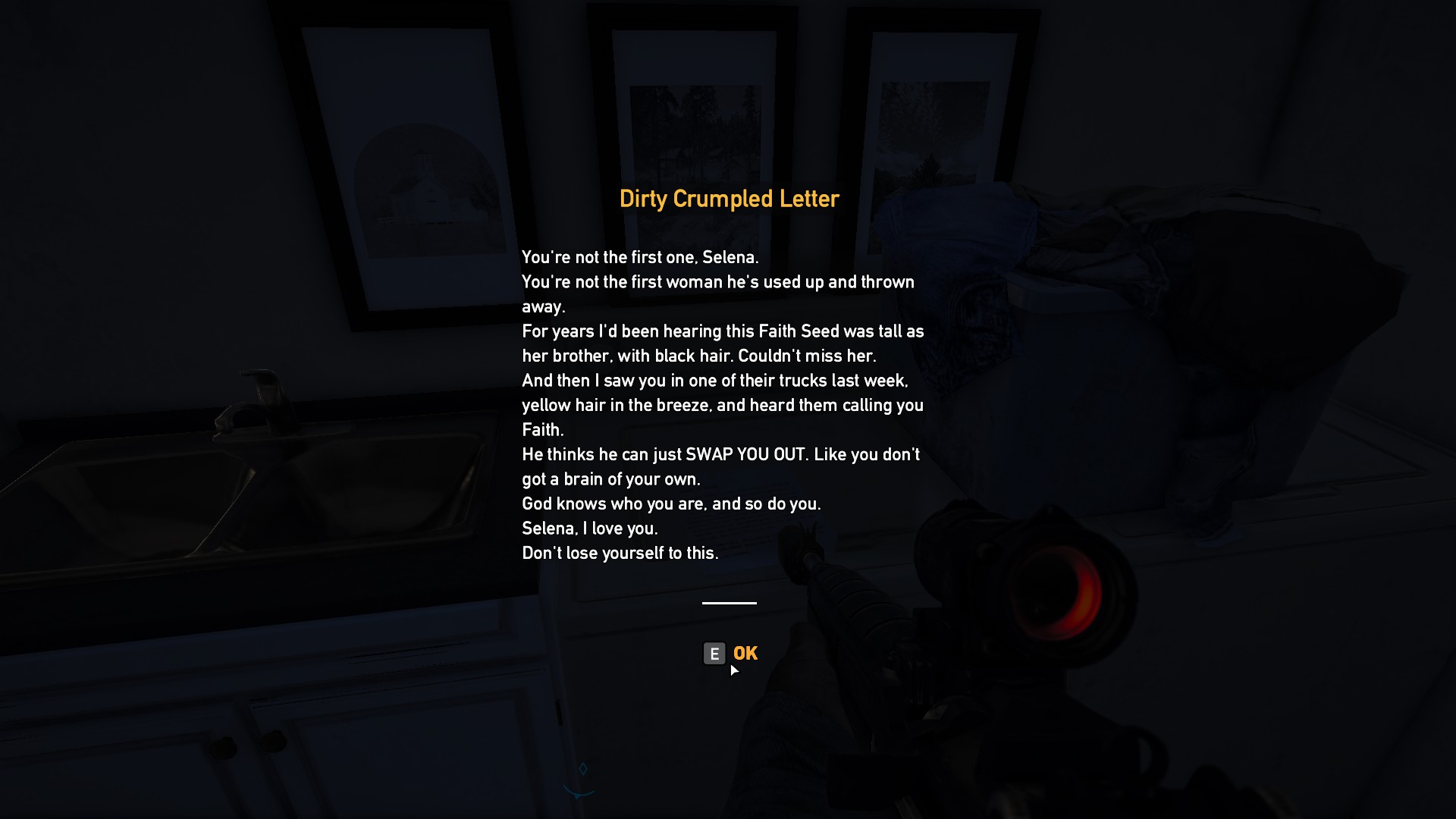

Faith Seed isn’t so much a name as a title. The woman currently holding it is just the most recent in a long line of people who have been taken advantage of by Joseph, and the cult by extension. In your final confrontation, you learn that Faith’s redemption was a false one under a cloak of ultimately hollow religion. She reveals that she was plied with drugs and threatened by Joseph when she was still practically a child to assume her current role. Manipulated when she was alone, addicted, and desperately needed help, to turn her into the manipulator of others that she is today. This is confirmed by other documents you find throughout the game. Notes from caring friends, and even those who were close to previous Faiths. In Far Cry 5, the character of Faith is both deceived and deceiver: tragic, like her brother John.

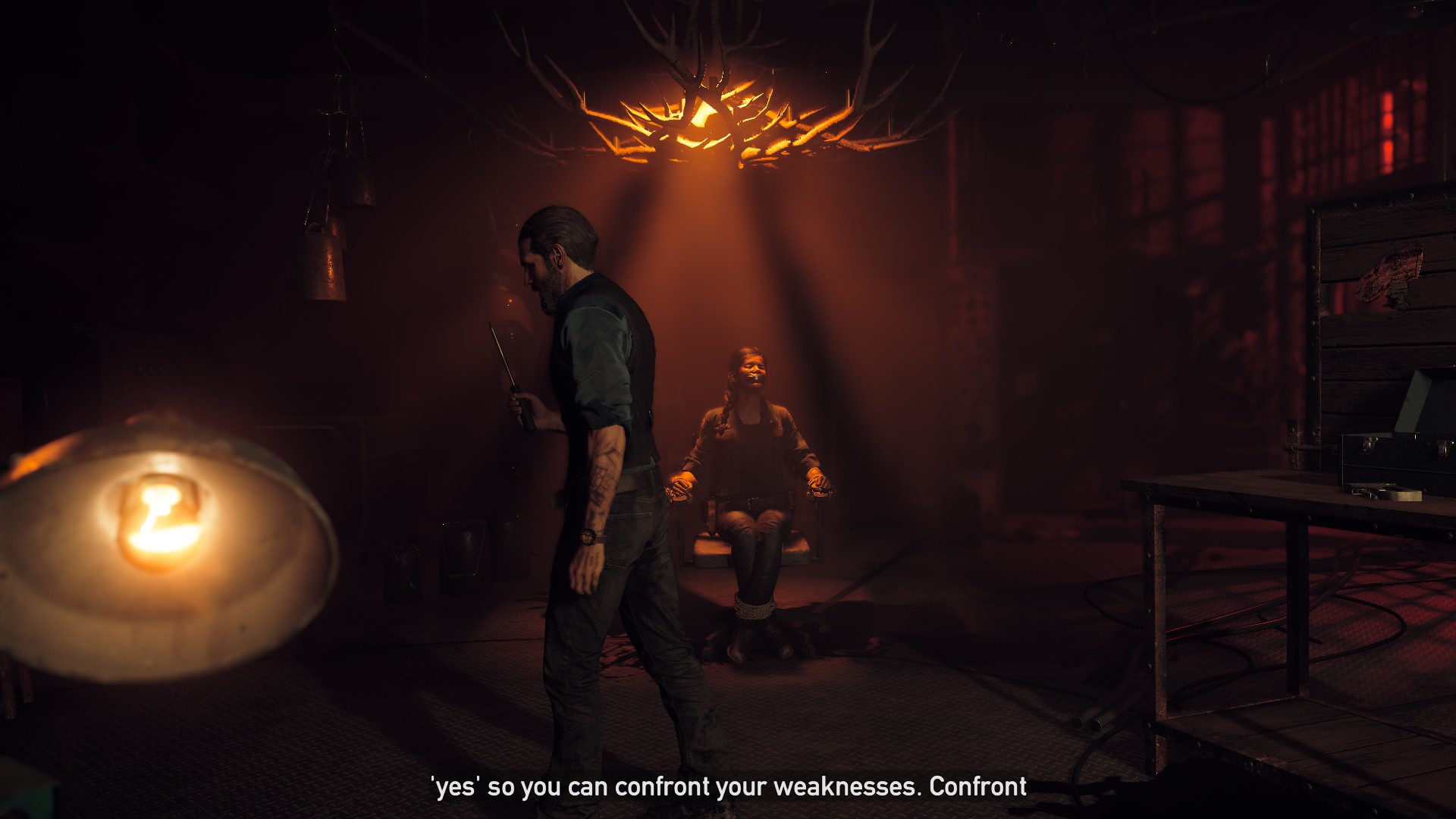

When you’re strapped to a chair in John’s torture dungeon, things don’t look great. He begins to monologue, talking at the player camera in the type of sequence that has become infamous since Vaas Montenegro screamed about the definition of insanity in Far Cry 3. However, when he begins to speak about his past, the theatrical posturing suddenly falls flat. John Seed’s story is one of child abuse. Internalizing the need for pain, he found ‘the power of Yes’ by seeking out every source of agony and debasement he could find. Suddenly, the cartoon sadist becomes a damaged person with a very sharp knife. Someone whose personal struggles have been redirected by leadership in the cult, into their very worst forms. Someone who was redeemable once.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The swings in characterization and nuance are so drastic that they pull you out of the loop of blowing shit up and running that you tune into to play Far Cry, and question the very premise of the experience. If these villains are people...what do their deaths mean? What is the game saying about them?

Is this the point?

And that’s the thing about Far Cry 5—it has so much content, and says so many different things (often with an admirable amount of internal commitment), that a search for one overriding message is futile.

Shooting brainwashed cultists to the beat of Disco Inferno with an enthusiastic pyromaniac, you could easily believe Far Cry 5 is a goofy if tone-deaf romp. Searching for what is possibly a certain alleged tape with a loud undercover agent, you might see Far Cry 5 as a GTA-esque satirical morass. Murdering cultists next to a massive bear you can pet after he’s torn your enemies throats out, you could conclude Far Cry 5 just offers an over-the-top setting for an exciting FPS. Depending on the missions you played, that would seem correct for the most part.

However, you might then play a mission where you take Nick Rye, one of your recruitable companions, to the hospital with his pregnant wife. That’s it. That’s the mission. A moment of humanity at the end of the world that immediately contradicts whatever single comfortable narrative you believed you found.

Apart, any one of these scenarios could be representative of a specific tone and subject matter for an experience. Together, they’re the confused mess that has become Far Cry’s modern identity...Which is why I’m increasingly excited about its divisive ending.

At the end of Far Cry 5, the Collapse occurs. Mushroom clouds rise in the distance as you race to a nearby fallout shelter, only to find yourself taken prisoner by Joseph in the deserted bunker as a captive member of his new ‘family’. All your friends are dead, Joseph hisses “I was right” into your ear, and he sits in a chair across from you, triumphant.

When I first saw this ending, I was frustrated. There was no closure. No final message to rearrange the many, many thematic pieces I had been given into even a partial picture. Then, I realized that...Joseph might have a point. Maybe the sole, inevitable way for Far Cry to move on was to destroy its world first.

Someone has to be right—why not him?