The art of creating the perfect first game trailer

Trailers find many different ways to show off a game in the best light.

Everyone watches trailers, whether as part of a big industry showcase such as E3, on Youtube, or on a Steam store page. to generate interest, trailers need to simultaneously capture your attention and efficiently deliver essential information about plot. the exact method differs a lot depending on the game’s genre and its unique selling points, but the basic aims are the same. i spoke to developers and a marketing team to find out what a good trailer needs.

“Game trailers are often not clear enough about what you end up doing. Is it a narrative game without a fail state? Is it a survival game? All this really basic information is missing, but it’s really important in games because of the great variety of experiences games offer,” says Game Designer (and former PC Gamer Section Editor) Tom Francis. “Often when you’re making a game you don’t realise what it is you haven’t said about your game.” The trailer for his game Heat Signature features footage which is explained via a humorous voiceover. As a result, viewers get a sense of how it plays and the tone it’s going for.

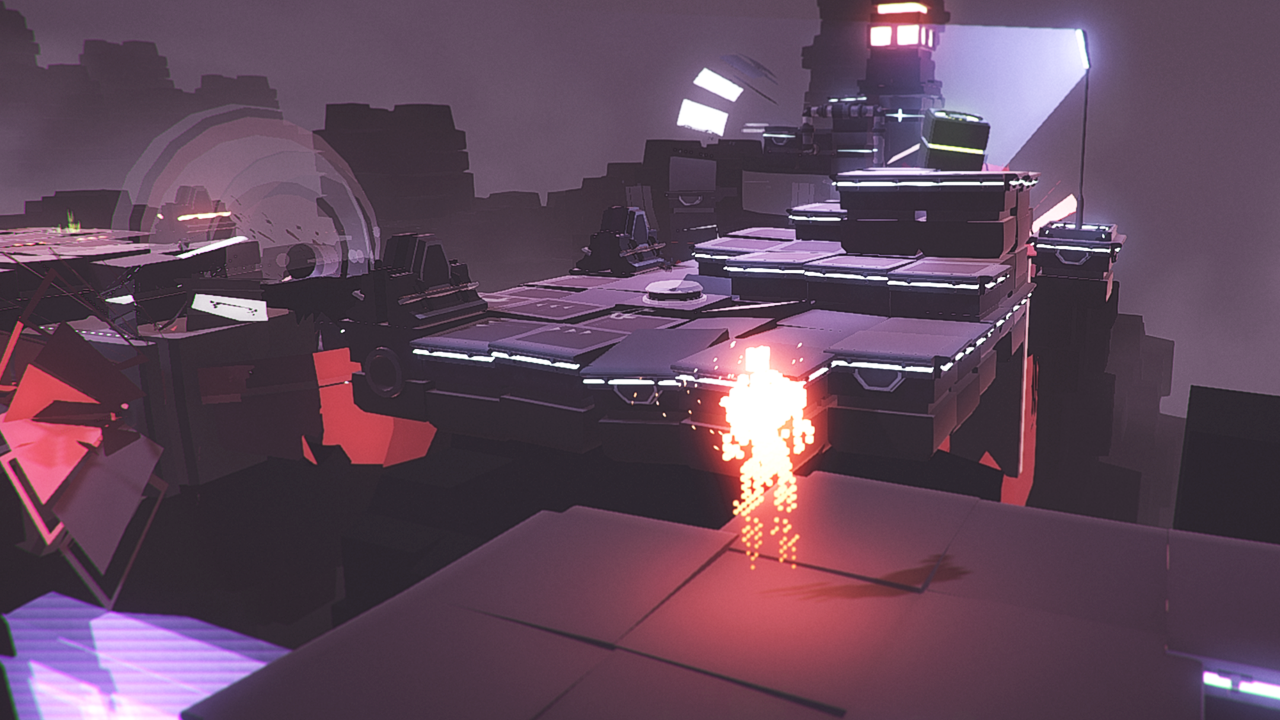

Phi Dinh and his team at Phigames took a different approach with the trailer for action platformer Recompile. Instead of footage or a storyboard, they took a piece of music as a starting point. “I’m keeping things intentionally vague that way rather than allotting explicit time frames to show off game mechanics or combat, “ says Dinh. “It’s quicker than asking a composer to make the music fit your very specific vision.”

Phigames also recognised Recompile’s strong visual identity as one of its selling points—with a player character that immediately stands out, and a unique environment inside a computer mainframe. The resulting trailer uses the sparse opening bars to establish the scene and introduce the running player. As the music becomes more complex and more intense, the trailer brings in footage of increasingly varied and violent actions, building from simple jumps to laser fire and explosions.

One function of a trailer is to offer a vital first impression. That means developers and publishers often need to figure out how to show the game in its best light while it’s still under development. “Indie teams tend to polish mechanics and environments right from the beginning of the development cycle,” says Dinh. “For Recompile we prototyped all of our mechanics from the beginning in order to build an extremely polished first level we could then use to make the trailer.” Tom Francis, however, prefers to present you with a single polished trailer once the game is complete and ready for purchase. Before the game’s release he’s already captured himself playing it and shared raw footage via social media, so the trailer acts as more of an official statement.

Marla Fitzsimmons, marketing manager at publisher Fellow Traveller, notes that, “Just as the creative approach to the trailer differs from game to game, when we release the trailer also depends on the state a game is in.” Announcement opportunities like E3 introduce further complications, meaning a team might need to use footage that’s more raw or from a purpose-built level instead of the game per-se to meet the deadline.

While some studios prefer (or can only afford) a single trailer, others use a multiple trailer approach. A series of trailers over time can help maintain interest in a project, or allow the developers to show elements of the game off in more depth. A publisher may also have the budget to commission several trailers that focus on different aspects and thus appeal to different potential player bases. “With indie games one trailer is often enough to summarise what’s compelling about a game,” Fellow Traveller’s Managing Director Chris Wright says, which is reassuring news for those who don’t have the content or budget for more.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Showing and telling

Fellow Traveller commissions editors such as Derek Lieu to make their trailers. Editors can request custom game builds from developers to help with the process, allowing for different camera angles, letting them switch from day to night instantly, letting them zoom in on the action and so on. Lieu used one such build to let him showcase particular interactions in his trailer for Where the Goats Are, a narrative game by Lambic Studios. Not all games are easily showcased, though. “For a platformer or an FPS you can easily show what the gameplay looks like,” says Wright. Text-heavy games are harder to show and less interesting to watch so you need to go beyond game footage. “We may use voiceover to substitute text or focus on the overarching plot,” adds Wright.

After all the work that goes into a trailer, it has worryingly little time to make an impression on its audience. On his blog Derek Lieu warns against logos at the beginning, since a viewer’s attention wanes after as little as five seconds. Yet the time it may take to portray a game through its trailer once again varies. An indie game reveal might have a one minute trailer, a big budget title may stretch into the five minute range. Ulimately the point is not to reach an arbitrary timestamp, it’s to interest you in the project and then deliver key information such as a release date or a call to action like “Wishlist on Steam now”.

Fitzsimmons summarises why the trailer is the most important game marketing asset. “The job of a trailer is to communicate a pitch, which for us is often no more than a single sentence—a specific feeling we want to convey, or the thing that makes a game unique,” she says. Francis agrees, “After I’ve put my best foot forward and showed you what it is we have to offer all that’s left for me to ask is ‘Do you want it?’.”