The next BioShock should return to the fundamentals laid down by System Shock 2

A true sense of place is well-earned, as Irrational’s first-ever game demonstrates.

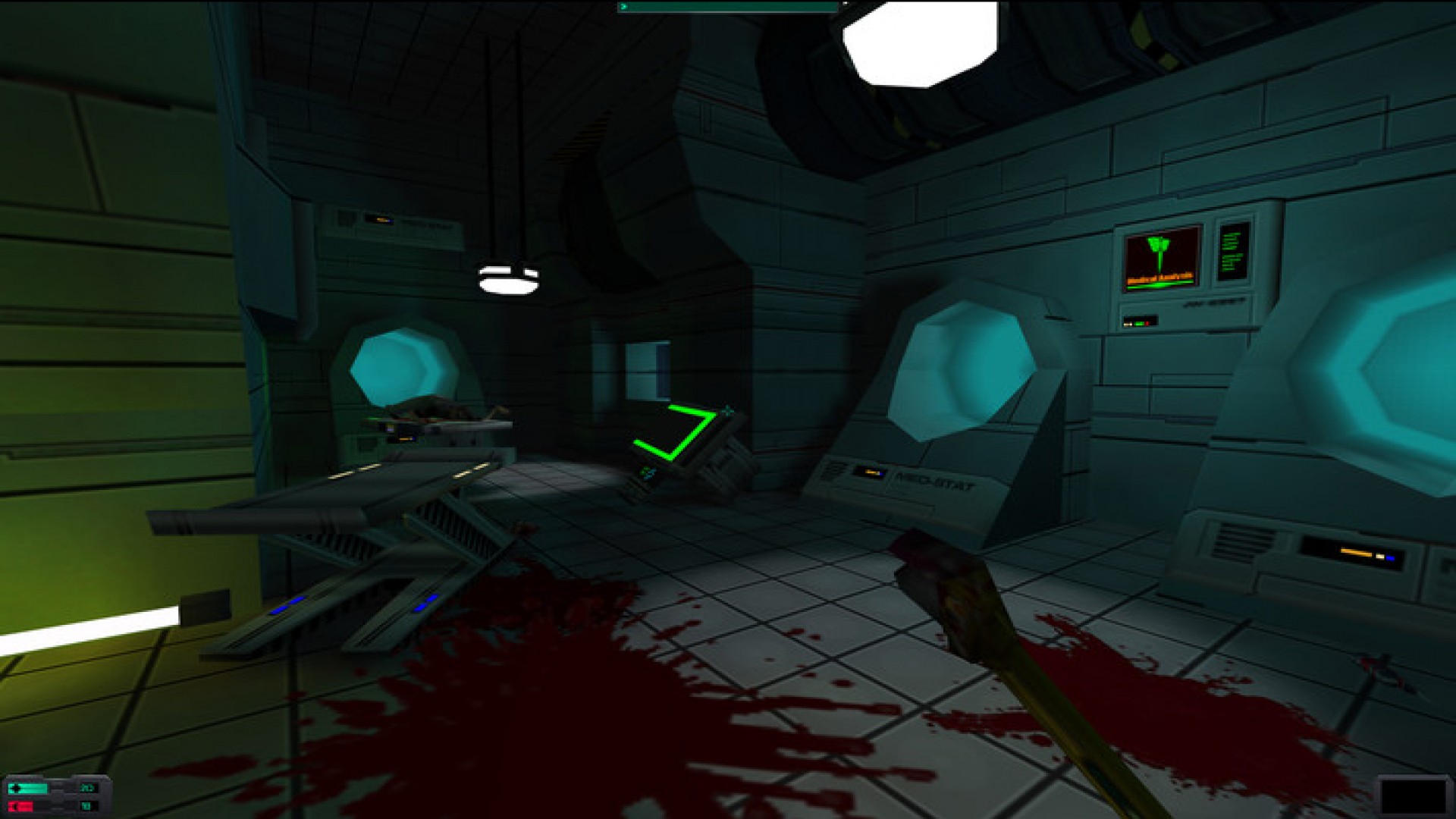

Look along the top shelf of the laboratory stockroom on the Med/Sci deck of System Shock 2's Von Braun, the faster-than-light vessel named for the father of space travel, and you'll find samples of various chemical elements, kept in tubs the size of peanut butter jars. Lined up in roughly alphabetical order, there's Antimony, Barium, Californium, Fermium, Gallium, and Iridium. And right on the end you'll find me, crouched tightly into the space between the shelf and the ceiling.

There are a couple of good reasons for that. Firstly, up here, I stand a better chance of dodging the visual and auditory sensors of the hulking security robot patrolling the adjacent corridor. Secondly, I'm well situated to read the labels, and apply the right element to the psionic monkey specimen I'm carrying in my inventory. That way, I can figure out how the ape brain works—and know exactly where to hit its exposed cerebrum with my wrench.

The thing is, I know I'll end up back here, hours later. I'm bound to find some viral weapon or hunk of annelid flesh that needs coating in Cf or Ir if I'm to understand it—and I'm not likely to find all the same elements on the Command deck, or Hydroponics, or Recreation. But there are too many jars here to pack into my bag. So when the time comes, I'll embark on a grand backtracking exhibition. And in the process, the Von Braun will stop feeling like a series of game levels, and become a three-dimensional place in my memory.

This is the characteristic that has most struck me while replaying System Shock 2—both in anticipation of the System Shock remake coming in March, and the more distant prospect of BioShock 4. The latter is in development at a new 2K-formed studio called Cloud Chamber, which is home to some former developers on the series, and focused on building "yet-to-be-discovered worlds". I hope that team feels empowered to create something truly new to inspire the sense of wonder that came with taking the bathysphere down to Rapture, or the rocket up to Columbia. But I also hope they look back to BioShock's roots, in Irrational's very first game.

Ken and barbarism

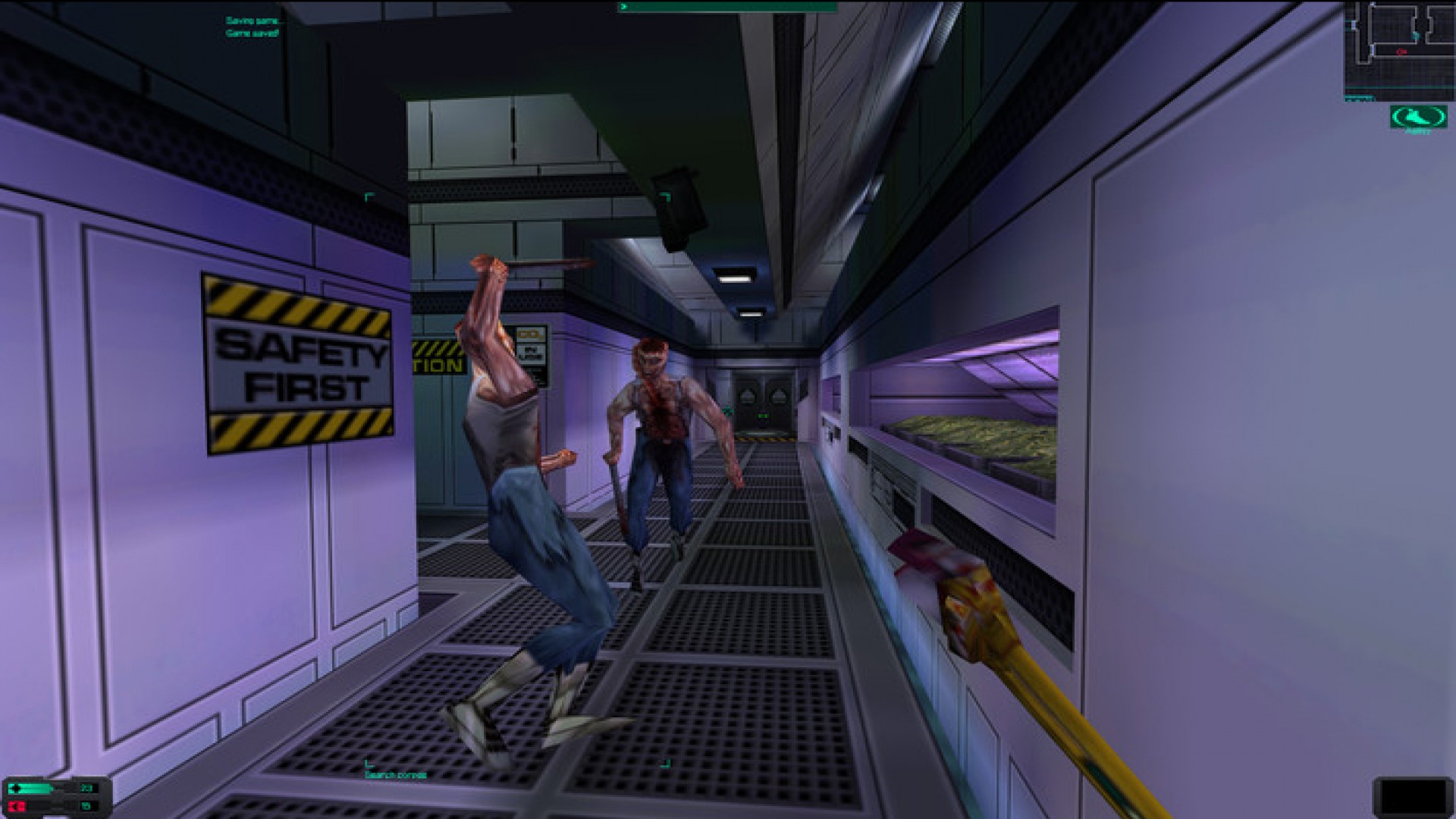

System Shock 2 was Ken Levine's debut as a lead writer, and feels remarkably like his later work. As in BioShock, there's an ideological battle—on this occasion between the AI dictator Shodan and a hive mind called The Many, stand-ins for fascism and communism respectively. And this dichotomy is explored through the perspectives of dozens of characters, captured in audio logs scattered throughout the space station. The tight, dilapidated corridors are populated by haywire turrets, rotating cameras, and the moaning husks of former humans, which you destroy or circumvent by guile, gathering weapons and tools as you go. There's no other option: space, much like the bottom of the ocean or an endless sky, provides no escape for a pedestrian.

Yet there's a pervasive sense of permanence to the Von Braun that Irrational left behind in its later projects. BioShock Infinite has distinct districts analogous to System Shock 2's decks: the downtrodden Finkton, unnervingly idyllic Raffle Square, and Battleship Bay, which evokes Brighton Beach. But together they make up a rollercoaster ride, a series of one-shot setpieces snapped together like pieces of track. There's no turning back. By contrast, the Von Braun persists the whole time you're playing, from top to bottom—accessible via the elevator that acts as your portal between decks.

Returning to previous areas in System Shock 2 isn't just a fun hypothetical—you're given many reasons to retrace your steps over the course of the game. Healing is expensive, and can easily hoover up your supply of medical hypos, which is limited by a tight and punishing resource economy. So you'll want to make regular use of surgical units, which refill your hitpoints, but are few and far apart. Their locations quickly become burned into your brain, rare buoys for a survivor adrift at sea.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Then there are the alien materials, extracted from warped skulls and pulled from sacs where The Many's larvae nest. Those are what take you back to the chemical stockrooms—part of a research path that Irrational dropped when it modernised the formula with BioShock. And periodically, you'll come across codes for the doors of weapon caches on previous floors. Given that your guns deteriorate without maintenance, an untouched stash of grenade launchers and EMP rifles is worth any detour.

Engine ear

Even a nondescript room can become a treasure trove in retrospect. You might wisely drop a gleaming assault rifle because it takes up three slots in your inventory, and is unusable until you've fully developed your weapons ability. But once you've unlocked the requisite RPG skills, that same gun might acquire new lustre. And, since a dropped object remains in System Shock 2's world forever, the only limitation on hunting it down is your own memory.

Levine's story encourages you to ultimately wander the floors of the Von Braun as if you own the place. Before you can leave the ship, you have to undertake a tour of its various decks, restoring power and pushing buttons in locations made familiar by past victories.

Individually, none of these ideas are killer features for an immersive sim or first-person shooter. They might even strike you as an annoyance, pushing you to stare at the same old bloodstained walls rather than gambol through entirely new environments. But together, they instill a powerful belief in the Von Braun as a coherent space—not a living and breathing world perhaps, but one that's humming and beeping in all the right places. In fact, the ambient noise changes convincingly as you ascend the ship—from the bassy throb of Engineering, to the polyphonic buzz of Recreation.

Cloud Chamber needn't slavishly revive the model Irrational laid down with its first game. There's plenty about the way System Shock 2 works that would be considered obtuse today—and a new BioShock ought to be bold, rather than nostalgic. But if the developers were to backtrack to the Von Braun for just one thing, they should bring back that persistence, which lends the ship such a powerful sense of place. After all: what are the Shock games about, if not the story of a place?

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.