The making of Total Annihilation

How Cavedog's influential 1997 RTS came to be.

Retro Gamer is an award-winning monthly magazine dedicated to classic games, with in-depth features from across gaming history. You can subscribe in print or digital no matter where you are by clicking this link. Its current issue celebrates the 40th anniversary of Space Invaders.

This feature originally ran in Retro Gamer 183 earlier this year. To subscribe or find out more, head here.

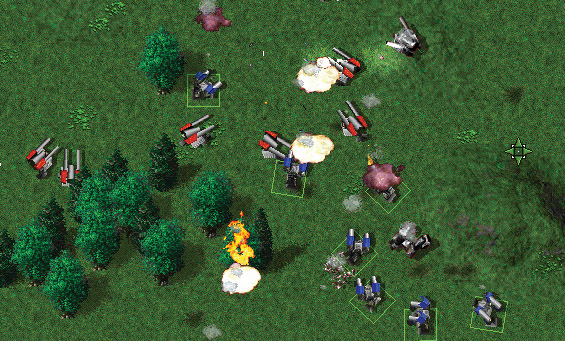

Total Annihilation came out when games, and RTS games in particular, were quickly evolving. By the mid-Nineties, PCs were capable of capturing the necessary scale of battles, and online gaming was about to become a phenomenon. And it was that world Total Annihilation creator Chris Taylor was waiting for. We caught up with Chris and asked him about the game's origins.

“It evolved from a bunch of experiences that I had while developing games for most of my childhood, but there was a moment, while I was playing the original Command & Conquer where I saw many of the ideas coalesce,” Chris says. “For example, I was always a very big proponent of doing things in true 3D, but the computers just couldn’t handle it. I had developed many techniques for sort of ‘tricking’ the computer into making it look 3D and saving a lot of calculations. And what’s kind of crazy is that I developed a lot of these while working on baseball games like Hardball II and Triple Play Baseball. Anyhow, it’s a lot of factors that all lead up to a moment where you have an idea for a game.”

Total Annihilation had many RTS contemporaries, with Z and Command & Conquer: Red Alert both released in 1996, and Total Annihilation sharing 1997 with games like Age of Empires and Dark Reign before StarCraft came out in 1998. Total Annihilation enjoyed immediate success and the kind of glowing reviews any games studio would dream of. But was it helped by the general popularity of RTS games at the time, or was it the other way around?

“That’s something I can only speculate on really. I totally agree that having all those RTS games come out around that time made the RTS genre very popular, and top of mind [with gamers and the media at the time]. I don’t know how much TA contributed to the genre’s success, but I think more specifically it helped advance the idea that a RTS could be ‘over the top and insane’ and have more advanced control schemes. This is something I am still passionate about today.”

Indeed, Total Annihilation was considered revolutionary in many ways, like its excellent AI, new grouping techniques and the scale of the battles. Then there was the introduction of the Commander, a central, all-important unit to the battlefield that was a big hit at the time. Chris remembers the inspiration for it clearly.

“I always believed that RTS was a true strategy game, and having played a bunch of chess, I felt there was a place to insert some of that,” he says. “But besides needing a king on the board for the enemy to focus on, the player needed an avatar, a place to feel like they are connected to the game experience. I imagine I wrote something like this in the design, ‘The player needs to feel like they are part of the game, and the Commander accomplishes that.’ I’m paraphrasing, but you get the idea. Although, one could argue that it really didn’t accomplish that, per se, but it did give the player a sense of, ‘hey, don’t mess with my Commander, or there will be trouble!’ It makes the game more personal. So, if you follow the design logic and say that if the Commander dies, the game is over, then the Commander needs to be powerful.” Placing a metaphorical king onto the field of battle came with some unintended consequences, though.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“There was a lot of stuff packed into the game. We were pushing the boundaries in as many areas as we could, and when we stopped, we just picked that up where we left off with Supreme Commander. As for the challenge of balance, that was handled by Jacob McMahon, who although had never done that kind of work before, did a fabulous job, and spent hours and hours poring over the numbers to balance the game. The Commander added an extra wrinkle, and in some ways needed special attention… and yet, ‘Command Napping’ still snuck past us! We never saw that coming.”

What Chris refers to here is the concept of ‘Command Napping’, as it was referred to by the TA community. As the success of your campaign often relied on your Commander surviving and being active, it would become a tantalising target for opportunistic players.

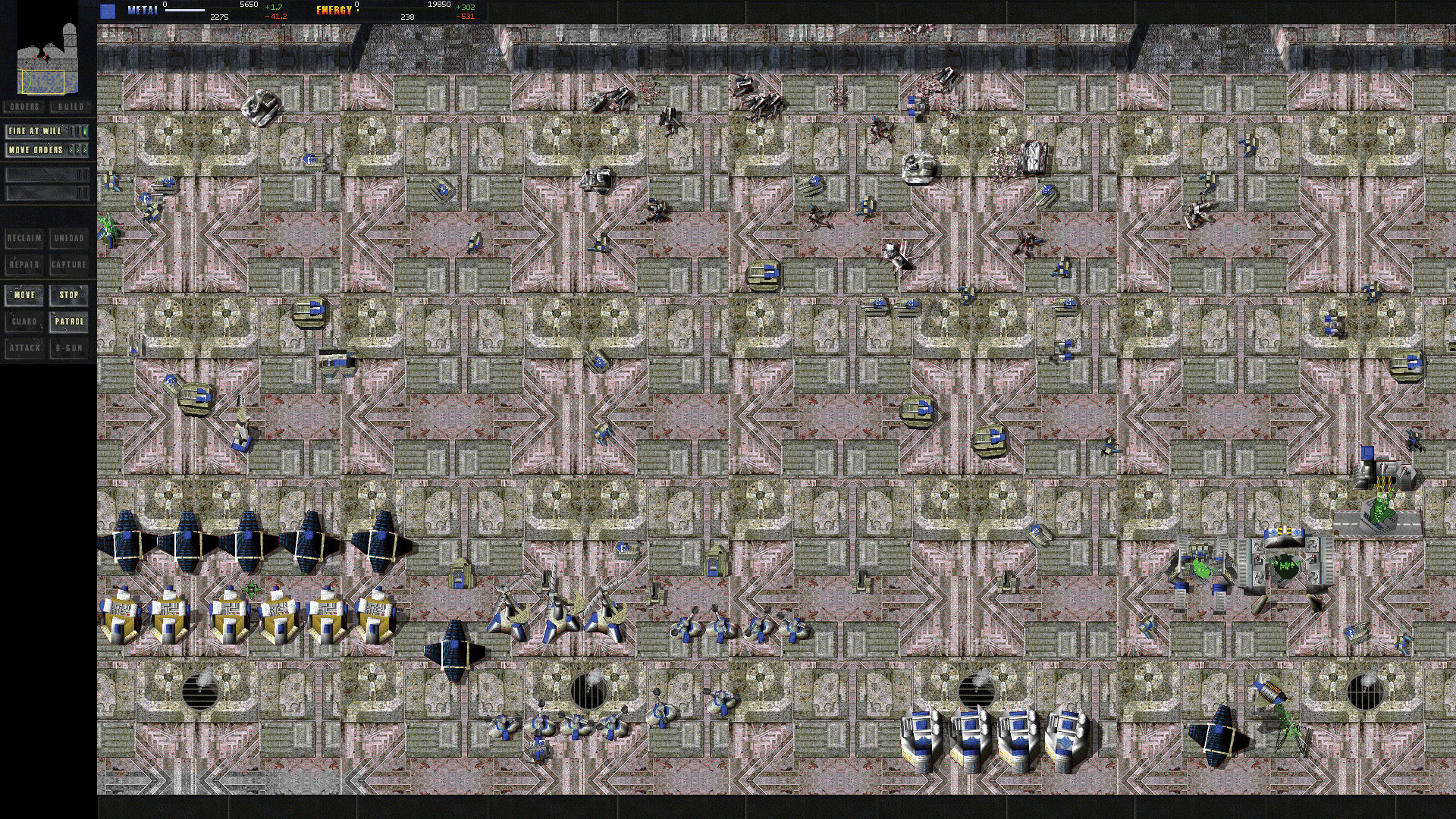

Nigh-unkillable as it was in a firefight, some devious, yet ingenious, gamers found a loophole to taking the Commander out of the game: build an air transporter, such as a Valkyrie or Atlas, fly it over to the enemy Commander, pick it up, and then just fly the aircraft to the far edge of the map, rendering it useless to the opponent, thus crippling their building and development capabilities, which relied heavily on the Commander. Yes, it would have required building several dozen aircraft in the hope that one survived long enough to pick the Commander up from deep within its own territory, but if you pulled it off, it didn’t just give you an advantage—it gave you a great sense of villainous joy.

This was merely one of the ways in which Total Annihilation dedicated player base found ways to get the most out of the game and its hundreds of units. In many scenarios, especially for experienced players, one side, Arm, would find a tactical advantage over its opposing side, Core. That, Chris explains, was also unintended: “We never intended for one side to be more powerful than the other. We had always planned (and did for quite a number of months) to release new units, which we believe would continue to shift the balance of power back and forth between the two factions each week. I think that sort of worked.” For those with a taste for the ruthless, The Core Contingency expansion featured 75 new units, including devastating, balance-reinstating Core units.

When Total Annihilation came out, it was an instant success, both critically and commercially, and it took Chris—and the Cavedog management—by surprise. “I believe it sold almost 500,000 units in the first four-to-five months and that blew people’s minds,” Chris says. “That was 20 years ago, which was a different time than today with the distribution of Steam and GOG.” This was especially gratifying, as TA was Cavedog’s first full game release, and the development had been a challenge, in particular the schedule, as Chris explains: “Time and reflecting on the past changes things. I feel like it was working seven days a week for 20 months. That was hard, but maybe the more metaphysical challenge was just getting everyone on the team and in management to keep the faith. Holding that vision together with all the different people and personalities was difficult on an entirely different level.”

Even today, 21 years after its original release Total Annihilation is still played by a dedicated group of players. As for the reason why, Chris says this: “That’s a tough one to answer, but ultimately maybe there’s a comfortable familiarity to it, especially if it was one of the first RTS games that you played in your youth. And then if you try to play a more modern RTS they can be overwhelming and you need to learn all the new units, which is a lot of work. I think gaming should be about fun, not work, so it’s just more fun to play something you know and understand and can just jump in and enjoy. I think there is also something about the graphics that make it accessible, kind of like Minecraft with the 8-bit stylised graphics. Even I don’t love modern games when they throw a ton of complex gameplay at me, I like to take it a little slower. But that’s not a hard and fast rule, it’s just me talking out loud here!”

Finally, Chris ponders if he were to make Total Annihilation again from scratch today, apart from having larger and more capable graphics engines at his disposal, whether he would change anything from the original incarnation.

“I’d try to stick to the core design,” he says. “I would resist the urge to just make it huge and over-the-top, although that would be so incredibly tempting. I think it would be important to really talk to the community and see what they are looking for and take that input very seriously. It might be great just to kind of go through a wishlist of things and then more naturally look for places to expand the game, i.e. add flow-field pathfinding, improve mod tools, fix weapon limits, add more AI capabilities, make the simulation lock-step synchronous, and make a state-of-the-art multiplayer and matchmaking server. I think there is a ton of cool things you could do before you even change the core gameplay, but eventually you’d really want to take a hard look at that and find new ways to take it to the next level… without messing it up!”