The art of crafting the perfect videogame safe room

The calm in the middle of the storm.

I think it’s safe to say there are few inviolable elements in videogames. It can often seem like anything goes, as in the pure chaos of each new world, players are tried, duped, terrified and thoroughly tested—we play games, and they play us right back. It could be weeping as you repeatedly stomp an already dead jump-scare Necromorph, worrying about your heart rate as you face off against Ornstein and Smough yet again, or watching, transfixed, as the causality of your in-game decisions is brought to bear in the most tortuous manner possible. Games take their toll, whether through intensity, horror, emotion, or simply sheer visual noise. Enter safe rooms, the wonderful answer to the question, "How do we get players to take breaks if they won’t stop playing the game?"

But that seemingly simple purpose disguises their true depth. Safe rooms are utilised in all sorts of ways—they can represent an element of progression, a method of travel, or a hub for player interaction, like the bonfires in Dark Souls. They can be a place of trade and upgrading, as well a vehicle pushing forward an overarching community narrative, as with the Tower in Destiny. And yes, they can also be a respite from the chaos of the game world. But no matter how varying their function, most of all, safe rooms are a rare element of security in worlds where few things are sacred.

In residence

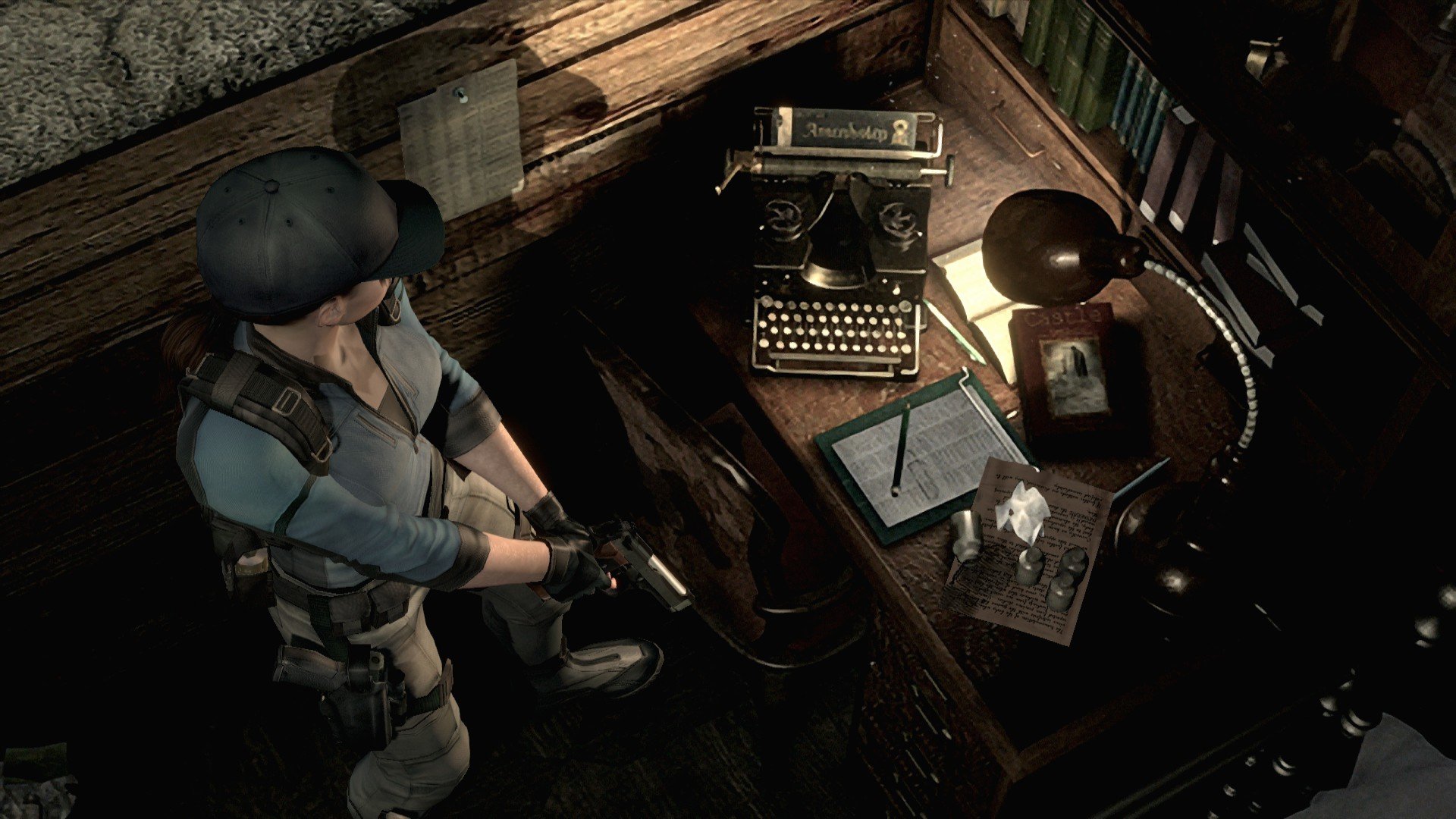

A common element in creating the atmosphere of a safe room is the musical score. You may remember Hollow Knight’s bench theme, Reflection; Darkest Dungeon’s camp theme, A Brief Respite; or Firelink Shrine’s melancholic string overtones. But few game series have perfected the art of the safe room theme better than the Resident Evil games—unsurprising, when you consider that for over two decades they’ve been putting us through hell. "We thought that having nothing but tension throughout the whole game would be exhausting for players, so we designed the save rooms as a safe place to take a breather from the horror," says Kazunori Kadoi, director on Resident Evil 2’s remake. "They were also useful to use as bases for exploring the game, so they added a strategic element." A room, a musical theme, and a typewriter—these have become the iconic elements of the Resident Evil safe room. But while each musical score has become synonymous with the idea of safety for many players, if you listen closely, they are actually far more insidious than you might have thought. "They may be 'safe rooms', but that safety is fleeting. You always feel like the moment you step outside the room, you might encounter some nightmare wandering the halls," explains Shusaku Uchiyama, composer on the original Resident Evil 2. "So it was indeed intentional for the music to be a mixture of peaceful and relaxing elements with a little touch of the uneasy about it."

This insidiousness, so often reflected musically, is a key element of the safe room dynamic—the unusual condition of being safe amid such a dangerous world, by contrast, can’t help but remind you of what is still left to face. "Effective horror is all about the balance and rhythm of tension and release; you can’t have all tension, all the time, or it just becomes tiring," reflects Uchiyama. "I think if you left the room silent or just had environmental sounds playing, it would actually play into the horror trope of the quiet moment before a shock, and players would be unable to relax because they would think something was about to happen." But even Resident Evil, as horrifying as it can be, understands the untouchable nature of safe rooms. As Kadoi reflects, "I don’t think we should ever break the rules as far as letting the player be attacked and hurt in the safe room. We’re supposed to establish rules by which you play and complete the game, and it would be unfair to break them like that just for the sake of a twist." Resident Evil’s iconic safe rooms and themes have undoubtedly gone on to inspire a large number of those we see in gaming today. But I still have a very important question to ask Kadoi: why a typewriter? "I recall that we simply thought at the time of original game that we needed an object whose function was to make a record of things, ie your progress, and which would not look out of place in an old mansion, and a typewriter seemed to fit the bill on both counts."

Cloud cover

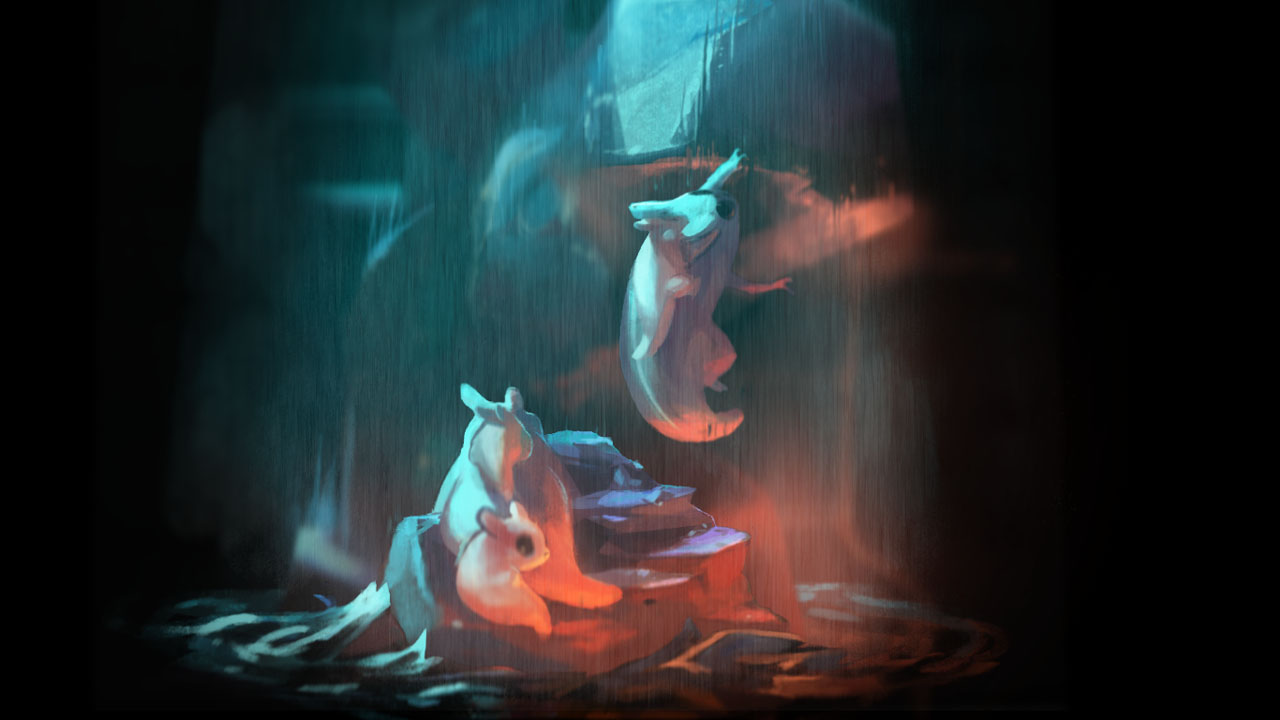

If ever there was a game in need of a safe room, it’s Rain World. Sneaking through the ruined city and its futuristic ecosystem, your animal protagonist, Slugcat, has to stay sharp. At any moment a lizard could jump out of a nearby pipe to grab you, a vulture may swoop down and haul you off into the sky, or you could even just fall into some carnivorous grass—and all the while the timer is ticking down toward the arrival of the cataclysmic rain. Rain World does grant players one respite however: the hibernation chamber.

"We wanted the player to intuitively embody the head-space and emotions of the player character: a lonely, lost, frightened small animal," explains James Primate, Rain World’s co-creator and composer. "The hibernation chambers had to play a major role in this of course. One of the consistent themes of Rain World is the return of the artificial to the natural. The 'hibernation chambers' are clearly artificial; some ugly rusted metal boxes, possibly for equipment or the maintenance automatons of some distant era. And yet, through the players occupation, it is re-purposed as the most natural animal thing: a den." The safety of this den is also rooted in a very animal sense of spatial awareness. “Those that have seen early prototype versions of the game might know that we initially experimented with much larger hibernation rooms which had two entrances, and we found that didn’t work. There needed to be a clear distinction between 'world' and 'shelter'. To have the effect we wanted, it needed to be a refuge."

Apparently the reason cats seek enclosed spaces with one angle of approach, is so predators can’t sneak up on them—Rain World creates the game equivalent of this. A tiny box with one entrance, providing a contrast to the dangerous open spaces Slugcat traverses throughout the game. Uchiyama explained that silence can be a horror-trope, but in Rain World’s case, shelters don’t reflect silence. Instead they reflect a sensory deprivation, sealing off the world behind pneumatic locks.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Inn trouble

The term safe room implies a relative smallness, but on the contrary, safe pubs, and even safe castles are just as likely. One of the finest examples can be found in Warhammer hack ‘n’ slash, Vermintide, in the form of The Red Moon Inn, a hub in which players can upgrade equipment and interact before heading out on their rat-slaying adventures. £The initial goal for The Red Moon Inn was to create an interactive space where players could spend time in between missions,£ says Victor Magnuson, game designer at Fatshark. £We felt that it would be more fun for players to be able to run around in a friendly space while waiting, rather than lurking in a simple menu." But as time passed The Red Moon developed as a community hub, with more features being added and with special events such as The Pub Brawl because as Magnuson explains, "What better way to celebrate than to get drunk and have a fist-fight with your best friends?"

So when the time came to bid farewell in Vermintide’s last mission, Waylaid, the old place went out with a bang. "The idea of having a surprise attack on the Red Moon Inn was something we had been kicking around since the early days of production and as Vermintide’s time came to an end, we felt is was a perfect way to surprise players," reflects Joakim Setterberg, level designer. "The destruction of the Red Moon Inn is in every way symbolic—it ties in to the End Times narrative that the enemy is never really defeated, indeed growing stronger with every setback." But this rare example of compromising a safe room was a necessary element in forwarding Vermintide’s community narrative, and in re-situating players in Vermintide 2’s wonderful base.

Taal’s Horn Keep is an incredibly varied example of a safe room—a sprawling gothic tower featuring exploration, combat practice, dialogue, crafting, trophies, treasure, paintings, and movement puzzles. But most of all, based upon the game’s inclusion and focus on class careers, it features a room for each character. "The characters' rooms were really fun to design, but we had to be wary of not falling into typical fantasy tropes. It would have been so easy to do a magical library for our Bright Wizard, defined by her intellect, or to let our Dwarf’s room be defined by his height." says Setterberg.

"Instead, we opted to design their rooms after their personalities and character traits. Sienna, being a Bright Wizard, has a room reflecting her chaotic and addictive relationship with magic. Anything not sturdy enough in her room is set on fire or destroyed. The mercenary Kruber’s room is the most human of them all, being very homely and reflecting his desire to come back to his farm and family. Kerillian, the Wood Elf, is of course found outside the Keep, but in a sturdy, practical shelter." Despite the fact we never see Vermintide’s characters living together, Taal’s Horn Keep is a safe room which plays a huge role in creating an implied co-existence. Alongside the game’s sparky dialogue, it helps foster a strong group dynamic, full of character quirks and backstory, synonymous with fantasy adventure.

Safe rooms affect a variety of purposes—at their most simple they offer temporary respite for those weary of the game world, but at their most grand, they represent hubs of community interaction and overarching narrative. In many ways they are bittersweet, insidious spaces whose very existence can’t help but remind players of the trials yet to come. But this strange balance reflects their true nature best of all.

Safe rooms are fixed points straddling the gaming timeline—a simultaneous reminder of all you’ve done and all you’ve yet to do. But they also represent a compact between player and game: out there we will throw everything we have at you, but this space is sacrosanct. Whether it’s a keep of mismatched adventurers, a bare room with a table and a typewriter, or simply the den of a Slugcat, safe rooms are the quiet before the storm.

Sean's first PC games were Full Throttle and Total Annihilation and his taste has stayed much the same since. When not scouring games for secrets or bashing his head against puzzles, you'll find him revisiting old Total War campaigns, agonizing over his Destiny 2 fit, or still trying to finish the Horus Heresy. Sean has also written for EDGE, Eurogamer, PCGamesN, Wireframe, EGMNOW, and Inverse.