Special Report: Do you own your digital items?

When is your shoe not your shoe? If you answered “when it’s virtual”... well, that depends. If you made a virtual shoe yourself, it’s definitely your shoe. But if you bought it, it’s probably not your shoe—it’s probably only a licence for a shoe, although in the European Union you might be able to sell it on. On the other hand (or foot) if you bought it in the US state of Delaware, your heirs can inherit your shoe (although you probably can’t sell it).

In 2013, total revenue from digital gaming passed console games for the first time, hitting $9 billion in the US, compared with just $6.7 billion on console games, and just $220 million on boxed PC games (and $20 billion on shoes). Yet it’s unclear how many of those purchases are actually buying you anything that you own. Jas Purewal of Gamerlaw explains: “The vast majority of online services give a personal licence to users, which is not transferable on their death. So Steam, iTunes and Kindle all say users get a licence not property rights, so there’s nothing to bequeath. The real issue is online property rights are not yet regulated. So far technology companies dictate, while legislators and users are oblivious.”

Ignoring the licences for a moment, most countries have no rules at all, as Purewal explains. “There has been some legislation in Asia (particularly China and Vietnam) about virtual currency and virtual property. The US has passed some regulations about virtual currency but it’s really directed at non-game virtual currencies like Bitcoin. In the UK the concept of ‘digital content’ is being recognised legally—slowly—but there’s no specific rules on ownership of games virtual goods. The closest we’ve got was a case some years ago in which a UK citizen was convicted of criminal offences regarding misappropriation of Zynga poker chips; that was the first time to my knowledge that a UK judge was confronted with the issue of virtual goods in a game.”

This is nothing new—after all, we’ve licensed software like Photoshop for years, without assuming we owned it. The difference is the huge amounts of real-world money that people are prepared to pay for individual digital items, as that $9 billion reflects. So, whether it’s paying $11,000 for a Revenant Titan in Eve Online or $38,000 for a Dota 2 courier, people are increasingly gambling vast amounts of money on digital items, with a view to resale.

Similarly, many of us may have built up huge libraries of games, apps and media on services like Amazon and iTunes. We may share these with our families, using the in-built sharing elements of these services. Yet part of the contract that we agree to when we start using iTunes or Kindle is that the digital items we’re acquiring are ‘non-transferable’. There’s some confusion over whether that means the actual accounts themselves are transferable. (Of course, usability testing has shown that almost no one ever reads any of those contracts, so there’s a separate question about how enforceable they are.) Other types of accounts have intangible but very definite value—what is a Twitter account with 10,000 real followers worth, for instance?

For MMOs, account transfers in most games are illegal. The curious example that is Entropia Universe (see box) allows all forms of transfers, as does Second Life, but almost no other MMO does, and most firms shut accounts and ban account holders who’ve attempted to transfer characters. Despite that, game developers have been known to exercise their discretion. Blizzard has been known to transfer characters to heirs’ accounts, though they insist on a lengthy identity verification process.

Our laws simply haven't kept up with the technology.

In Europe, a 2012 European Court ruling (Oracle vs UsedSoft) made it legal to sell on (but not rent) used software, including physical and digital games, provided you delete it from your computer. However, a June 2014 ruling in the regional court of Hamm, Germany excluded downloadable digital content from that ruling. This second ruling was intended to cover just music, films and books, but there’s no clarity whatsoever on whether this covers games or digital items connected to games. After all, these are all mere bytes, so it takes some abstruse legalese to justify treating the code for an e-book or an in-game sword differently. Given that, it’s likely this ruling will be taken back to the European Court.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Whatever the situation, these new European rights do not apply in the case of online services. As Purewal implied at the beginning of this article, many rightsholders are increasingly attempting to portray their business as a service. Witness the way Adobe has changed its business model for Photoshop from a single-licence purchase, renewed at great expense whenever you upgraded, to a cheaper monthly subscription fee. You still have the same piece of software on your computer, but now it gets disabled if you don’t pay. Again, it’s likely that some enterprising pirate will take this to the European Court.

It’s different in the US, of course. There, the 9th Circuit Court ruled that as long as companies call what they sell a ‘service’ rather than a ‘sale’, they can stop people reselling it. And they definitely can’t inherit it.

Except it’s slightly different in Delaware. Here, the state legislature just passed a law drafted by the ULC (the Uniform Law Commission, an independent body dedicated to creating sensible laws across America’s mess of rules), which allows anyone whose will is governed by Delaware Law to pass any digital accounts along to their heirs.

“This problem is an example of something we see all the time in our high-tech age,” said Delaware Representative Darryl Scott, lead author of the bill. “Our laws simply haven’t kept up with advancements in technology.”

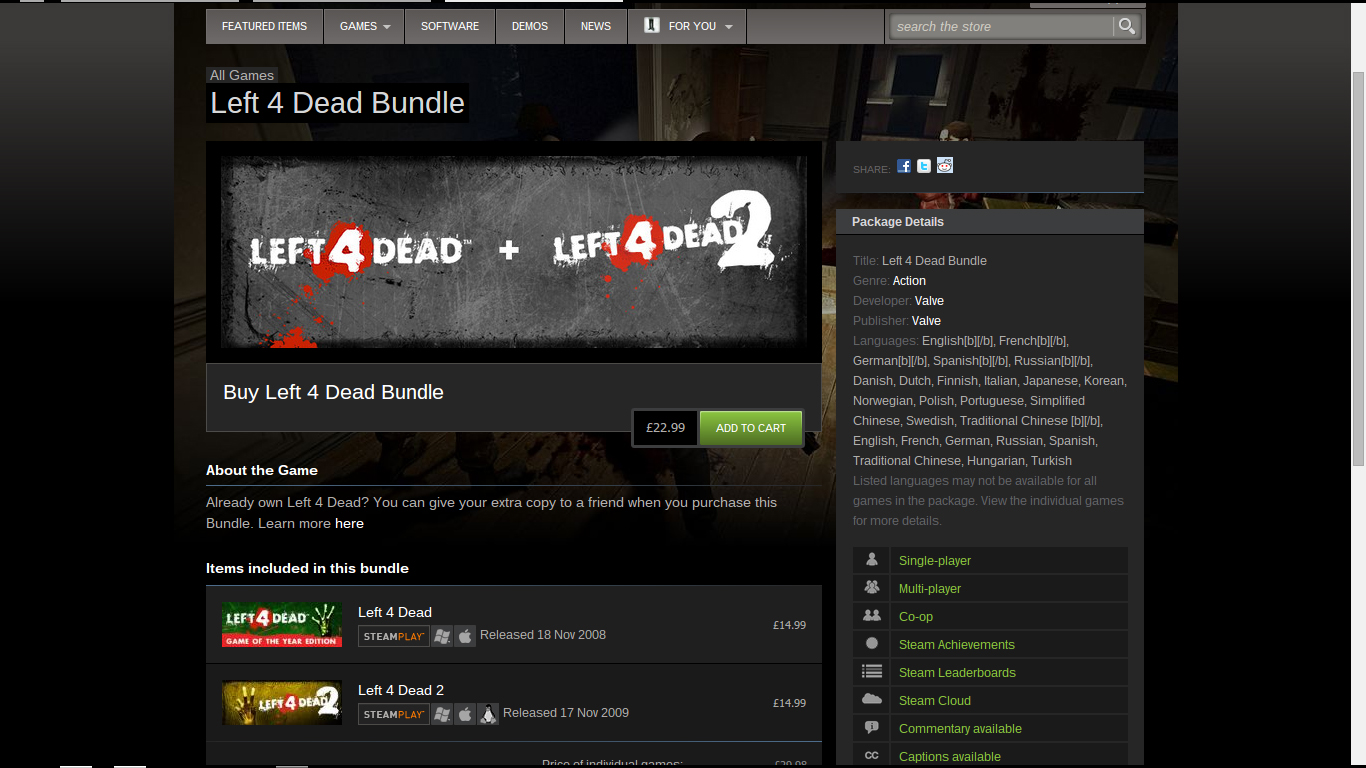

Of course, this is all academic if we’re consuming the majority of our games on a service like Origin or Steam. As anyone who bought The Orange Box while already owning Half-Life 2 will know, game trading is already functional in Steam, but not enabled (presumably because of the EC ruling we mentioned earlier). Players can trade or transfer their accounts, of course, but they’d have to be discreet about it, as it would infringe the platform’s Terms of Service, and possibly the EC’s ruling on software being a service—and whether it’s legal or not, if you got caught then you’d still lose all your games.

“The current older generations are not nearly as digitally switched on as the younger generations, and so the issue of digital ownership on death doesn’t arise so often,” says Purewal. “As the digital generations age though this question will come up more often, and at some point—we don’t know when—governments will have to do something about it.”

So at the moment, it appears that we have the right to resell games in the EU, but not in the US. We have no idea what our rights are with digital items in the EC. But, thanks to the EU and the ULC it looks like legislation is slowly moving in our direction, from favouring the big companies towards favouring the consumer. Pretty soon, the digital boot could be on the other digital foot.