September 10, 2025: Updated the article to reflect that World has had independent security/privacy audits and that it uses face authentication to attempt to combat the mule/proxy problem.

What a time to be alive: a time where we're being asked to prove we're alive and human. We have, of course, been 'proving' we're human for many years now, though it's always been easy to forget that's what those CAPTCHA tasks are up to.

Now, though, with AI becoming increasingly able to beat Turing tests and the likes, it's increasingly important to be able to verify whether someone online is a person or a bot. So, lest we head towards a vindication of the dead internet theory, we also need increasingly more accurate methods for distinguishing neurons from silicon.

This is no less true for gaming than anywhere else. Players using bots to cheat in online games is a real problem, and as AI gets more sophisticated, we can only assume the problem will get worse. Anti-cheats tackle this issue from one angle—checking program executables and so on—but another way of tackling it is to check that a user is a live person, a method that is often called 'liveness detection' or 'proof-of-human'.

I've spent the last week or so speaking to various expert humans and industry insiders to see what the state of play is for proof-of-human tech in gaming, and whether these technologies might pose any problems from a personal security point of view.

Although I came into these discussions sceptical about some of the proof-of-human methods because of their possible privacy implications, I'm surprised many of my initial concerns have now been alleviated. In their place, though, new worries have reared up. I'm still not sure whether we have a silver bullet that balances both our desire for user privacy and the ability to effectively prove liveness.

Eyeballs, please

I first heard about World (i.e. World Network)—the ChatGPT CEO Sam Altman, Max Novendstern, and Alex Blania-founded company—when it started proliferating oddly Orwellian-looking Orbs around the world. These Orbs scanned people's irises and gave them a bespoke WorldCoin cryptocurrency as a reward. (Side-note: the company originally went by WorldCoin, perhaps showing how central to the project the crypto side of the company was in the founders' minds.)

The goal, according to the founders, was to "scale a reliable solution for distinguishing humans from AI online while preserving privacy, enable global democratic processes, and eventually show a potential path to AI-funded UBI." UBI stands for 'universal basic income', ie, a minimum regular income given to people unconditionally.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Since then, however, and although WorldCoin is still ongoing, World seems to have pivoted to focus more on the iris scanning and ID side of things, and the benefits this might have for people in a time when it's getting harder to tell the human from non-human online.

Chief Product Officer at Tools for Humanity, a company that makes the tech for World, a company looking to create a global network of verified humans.

That's why, World says, it's partnering with Razer (for example) to help gamers know they're playing with and against humans, rather than bots. I spoke to Tiago Sada, Chief Product Officer at Tools for Humanity, a company that makes World's tech, and he explained how it works.

Essentially, you get your iris scanned by an Orb near you, and this gives you a unique token on an app, a World ID, which acts as a stamp to say you've been verified to be a live human. Razer can then check that you have this virtual stamp:

"The way this works is Razer has this Razer ID, so you can use your World ID to verify your Razer ID. So you basically get that blue check mark on your Razer ID. And then any game that already integrates Razer ID is able to use that signal to give you different things in the game, right? So some games are doing that for running human-only tournaments. Some games are doing that to have human-only items. Some games are running human-only servers. Some games use it for banning known bad players."

I wanted to hear about the dystopian-sounding Orb required to attain this virtual stamp, and in particular, its implications for user privacy. I don't know about you, but I don't fancy giving some company my personal biometric info just to be able to access some online games.

Thankfully, if World is to be believed, it goes about this in such a way that should keep user data private; in fact, it shouldn't store it at all:

"[The Orb] takes your pictures that it took, it encrypts them, and it sends them to your phone, and it deletes them from the Orb. So those pictures are only stored on your device. They're not stored on our servers, they're not stored on the Orb, they're only stored in your phone, and you can delete them anytime you want. So that's the first thing, we don't keep your data."

It also says all of its tech and privacy implementations can be verified because it's an entirely open platform—everything is open source:

"The Orb hardware is open source, the AI models that it runs are open source, all the backend pipelines and everything through biometrics are open source. The protocol itself, the identity protocol, is open source. And so not just governments, but you and I, or security researchers can and do constantly audit all of those systems."

Whether that's the whole story is another question. As cybersecurity expert Aimee Simpson, Director of Product Marketing at Huntress, tells me: "It’s hard to just take for granted that World does what they say they are doing without any external validation or auditing. If possible, I’d love to see third-party audits of their data managing practices to ensure they are doing everything they can to keep user data private."

We do actually have third-party audits of World's Orb and protocols (1, 2), and these seem to be positive ones. Although there are some recommendations for improvements, it seems that data is handled securely and privacy is maintained throughout the process, with minimal data capture, storage, and transfer.

The main point of contention might be that although no pictures of irises are stored, iris codes are. It's worth noting that the Worldcoin Foundation was recently ordered by Germany's data protection agency to delete data after it found that it had infringed GDPR by "storing the iris codes as plain text in a database" (PDF).

I suppose that because this refers to iris codes, this doesn't necessarily imply actual biometric data, but regardless, the regulator ruled the company hadn't complied with GDPR, and other countries have ruled against World for user privacy, too.

The Orb will look at you, it'll be like, yep, he's a real and unique human

Tiago Sada, Chief Product Officer at World

On the other hand, plenty of countries are running Orb verification seemingly without batting an eyelid. World says it actively works with some authorities:

"Governments have to go in and make sure that what you're saying is actually like the way the thing works, right? And I think that's a very healthy thing to do. And so we spend a lot of time with governments around the world explaining the technology, because it is a lot of new technology, and usually once they understand it they are very excited about it, and they actually go and ask other companies to integrate these kinds of policies."

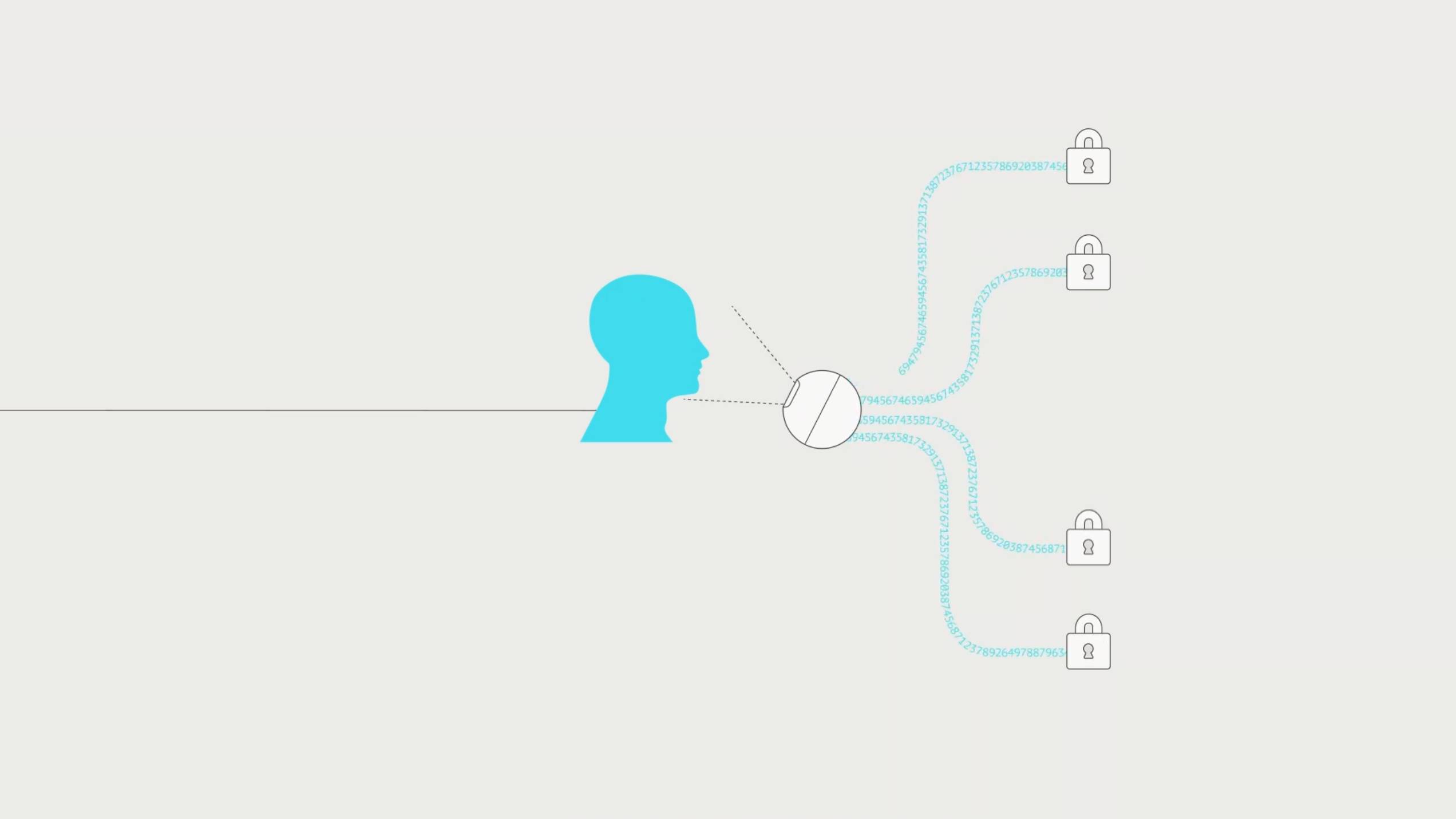

Iris scanning for proof-of-human is only one half of the privacy puzzle. The other is how we share that proof with services. On this front, World employs what's called a 'zero knowledge proof'.

Zero knowledge proofs

Proof-of-human should, in theory, be privacy-preserving. As Mark Weinstein, privacy expert and author, explains: "Proof-of-human doesn’t mean more data harvesting. The ideal system would collect the absolute minimum needed to verify a person is real, then delete it. The reality is our data is already out there. It's in the hands of social media companies, massive data brokers, advertising/marketing companies, governments, political operatives, and on the Dark Web. The ideal proof-of-human tech is designed to reduce your exposure by replacing constant surveillance and tracking with a simple one-time verification layer."

Privacy expert and author of Restoring Our Sanity Online: A Revolutionary Social Framework.

Zero knowledge proofs (ZKP) are the oft-touted means of achieving such a privacy-preserving verification layer. It's a way of demonstrating something without having to give the other party knowledge of whatever it is that proved it in the first place. For instance, it might be proving you are human without giving over the personal data that was used to generate the proof in the first place.

It is, as Sada told me, like getting a stamp on a passport:

"The Orb will look at you, it'll be like, yep, he's a real and unique human. It stamps your passport, it's verified, and you leave. But that stamp doesn't say anything about who you are. It simply says: I've been verified by an Orb."

This concept isn't unique to World, though. It's core to discussions surrounding the latest ID technologies. The UK recently saw such ZKP discussions in the wake of the Online Safety Act. This act twisted companies' arms to have them require UK residents prove their age to access adult content online.

Another company that implements ZKP in its most recent form of authentication is AuthID, and this company doesn't use an iris scan but instead a simple face scan. I spoke to this company's CEO, Rhon Daguro, and he explains:

"If your facial biometrics were stolen, you're kind of in trouble because you can't get a new face, even plastic surgery will not fix that. You would have to literally get bone structure reconstruction in order to change your face. So if you use inferior [non-ZKP] technologies, they store your face on a server and somebody were to steal it like a hacker, you're pretty much in horrible trouble, really bad trouble."

ZKP solves this problem:

"Essentially, what we do with our biometrics is we turn the biometric pattern into a public key and a private key. So once we know that it's Dr Fox, we say, 'Hey, we're going to create a public key and a private key.' And the only way to create the private key is with Dr Fox's live face. So your face will create the private key, the private key will do the handshake with the public key, and then we delete your face, and we delete the private key until you come back again.

"Then when you come back again, it must be a live face. So it must be Dr Fox in living, breathing flesh. You will generate the private key, the private key will do the handshake, and then we'll delete the private key and will delete your face. So in this pattern, we never store your biometric."

It's the same with World: You have some initial verification that does require biometric info, but that biometric info is then essentially deleted and replaced with an anonymised token that can be used in its stead. And this token can't be reverse-engineered to get back to the original data, so your original biometric info is completely safe.

In the case of AuthID, every time you verify your liveness with a photo, this is deleted, and a token is used instead. In the case of World, you only verify yourself once at an Orb; this biometric data is then deleted, and when you use your ID with other services, all these services ever access is your unique but anonymised token, your WorldID, that doesn't contain or refer to any of your biometric information at all.

Our Jacob Ridley explores ZKP and some of the hurdles it faces in the industry—not least of which being a current lack of standardisation between companies—in the piece I linked earlier, but I want to focus on just a couple of potential issues that surfaced during my conversations on the topic. Namely, the mule problem and the audit problem.

The mule problem

One thing that stuck out to me in these discussions with World and AuthID is the fact that, however fancy and privacy-focused these verification and authentication techniques might be, we're still ultimately using a digital token at the final stage to access our online services.

Whether we've been face-scanned and given an anonymised and hashed token in place of our picture, or iris-scanned and given an anonymised and hashed token in place of our eyeball data, there's a gap between getting that verification and using whatever service we're trying to use.

So what's to stop a real person from getting verified and then passing the reins over to a bot? Daguro explains that this is a very real problem:

"There's a fraud pattern called a mule … You actually use a live person to start the whole thing, and then they just hand over the account. It's almost similar to an Uber driver where, hey, I signed up, I'm legitimate, I got my car, I got my app, and then, you know what? I'm sick today. I got Covid. I'm going to hand it to my son to drive. He'll use my app, he'll use my car. They'll know none the wiser … And that's a proxy. We call that proxy fraud."

In this pattern, we never store your biometric.

Rhon Daguro, CEO and Director of AuthID

One solution is to get that verification every time:

"At the enterprise level, the compliance officers will not risk their jobs, so they will tell us: Rhon, if they [bad actors] use a biometric, they get in, how do we know it's them? I'm like, well, turn on the camera every single time."

It might seem that this solution wouldn't be open to World because you might think you get your iris scanned and then that's it. If this was the case, your World ID could, I suppose in theory, be used by others, either intentionally or unintentionally, for example if you lose your phone and your apps get broken into, or if you choose to log in with your World ID and then set your bot to the task of cheating in games.

World's solution to this is to use face authentication, just like we're used to. World's Face Auth solution works by comparing a picture of your face taken securely by the Orb but stored only on your device, to a live picture capture. This can be used to prove you're really the person who your World ID says you are.

This would then presumably put World into the same camp as other authentication services as far as mule problem goes. Unless photos are required frequently throughout your session on whatever service or app you're using, there's still a risk that at some point you swap yourself out to a bot after authentication, but it'll make it difficult for broad mule/proxy bot setups or ID theft or fraud to occur.

Assistant Professor at Champlain College who specialises in game programming and AI. He also runs the game development education site gameguild.gg.

The mule/proxy problem is widely understood. I spoke to Alexandre Tolstenko of game development education site gameguild.gg, a professor at Champlain College who currently teaches AI for games, algorithms, and game programming, as well as other programming and advanced AI classes.

He explains how ZKP can run into the mule problem even in very common scenarios, such as when you share a family computer with your kids, who then play games on your account. And if we're using a tokenised ZKP system, there don't seem to be any easy solutions:

"If you change the act of logging with something like face check or something like that, you still have the problem that we are not going to use the face check frequently, so once I have that, from that moment on, I won't be using that again. So it is still open to some vulnerabilities, such as this one that I told you about a kid playing the game in my name."

The audit problem

In my conversation with Professor Tolstenko, it seemed like a potential problem with ZKP proof-of-human tech might have nothing to do with the mule problem at all, but instead be to do with auditing.

If we use ZKP and delete biometric data to protect user privacy, then we have to really trust that the verification works. If there's been a problem with the initial biometric verification, there'll be no way of telling just from the ZKP hashed tokens alone, because those are by nature unable to lead back to any of the original biometric info that helped generate them.

This, Tolstenko explains, can make it difficult to effectively audit such solutions: "How can you do auditing? So how can I prove that that thing was exactly from that person? … I can only guarantee that hash was generated by this person if I have the original information."

However, he clarifies: "If you don't need auditing, that's fine, but if you need auditing, that's a problem."

We've seen that authentication companies do have security audits, but the problem Tolstenko is referring to here is about a specific kind of audit: one that can check how accurate the verification is in practice, when being used. The unidirectional nature of the proof and verification makes this impossible.

Such auditing would presumably be a big requirement for banking and fintech where the stakes are very high, but perhaps not so much for gaming. In fact, some argue that gaming should probably not require proof-of-human at all.

Cybersecurity expert Aimee Simpson tells me: "[Regarding] online gaming, I don’t think proof-of-human ID is necessary. While in an ideal world (with unlimited energy) this would be great, the sheer architectural and technological scale of this project would outweigh the benefits of having it. Creating complex online biometric systems and validating them would take so much planning, infrastructure, and energy that it isn’t worth doing in a low-stakes sphere like gaming."

Though I can't help but wonder whether standardisation of proof-of-human technologies will mean that the audit problem could be solved across the board, somehow, and this might then come to gaming. And if one uses an ID—World ID—for multiple things, not just gaming, then this might alleviate concerns like Simpson's.

I suppose at least World—to bring it back to the eyeball scanner and the audit problem—has everything open source, including the hardware, so one can inspect how the verification works to see whether it's up to scratch. There might be no way to back-trace World IDs that have already been verified to check that the biometric data aligns, but if we're sure there's an incredibly low error rate, then that should be good enough for most.

On this front, Rhon Daguro (AuthID CEO) had a bit of insight, as he explained that when it comes to biometric ID, "if you're an Apple user, they're claiming one in 1 million false match rate … But AuthID, just over the last two years, has been working really hard, and we just released a version roughly about nine months ago that is one in 1 billion false match rate … And [World is] doing biometrics, and their technology is like one in 1 trillion, or something crazy like that."

It's all a question of what level of accuracy is necessary for your use case. And it's not just about accuracy on its own, but also balancing that with ease of use and speed. Apple FaceID is super quick and easy, and the latest AuthID can be pretty quick, too.

World ID, however, requires travelling to an Orb location and getting your iris scanned. But on the other hand, once you've done that scanning just once, you've got your ID for life. And with the company having recently hit 15 million verified users, there's reason to believe many won't have a problem with this. And with World seeming to angle its ID as being the proof-of-human verification 'network', I don't doubt that'll be part of the argument to say it's worth the extra effort.

Radical solutions

Perhaps, though, all these solutions are thinking a little too 'inside the box'. ZKP is old news now, as are face scans and eye scans. Maybe we need something more radical. Tolstenko certainly seems to think so, arguing that we need a "new class of solutions" that can deal with the auditing problem whilst retaining user privacy. He doesn't know exactly what this solution will be, but he gives an example to get us thinking outside the box:

"I heard about a type of camera … that is based on sound, on echo location. So with that, it won't be leaking your image in any way. But still, you can have a type of fingerprint if the person is there, and you can even capture some particularities that could be used as identity somehow."

The goal, I think, would be to use data that can strongly verify we are alive and kicking, flesh and blood, bona fide humans, but have this original data itself be something that isn't usable, spoofable, or identifiable.

[World is] doing biometrics, and their technology is like one in 1 trillion [false matches], or something crazy like that.

Rhon Daguro, CEO and Director of AuthID

I'm not sure whether such a solution will be possible, but I certainly see why there might be a need for a new class of solutions.

Apologies if I'm speaking beyond my competence, here, but a move in the right direction might be to have a completely blockchained verification system—not only a blockchained token system, but a blockchained physical liveness verification system.

For instance, maybe a collection of blockchained computers that verify each new ID token as it's created, and part of the verification would include checking the hash is a result of a specific, standardised, open source biometric verification process, regardless of who this came from. This would put the process more squarely in the hands of individuals rather than companies or governments.

I could be waffling absolute nonsense there, but hey, I'd be remiss if I didn't at least attempt to throw my ideas into the gauntlet.

Where are we headed?

It's clear that while the more initially Orwellian-seeming solutions to the problem of bot-populated websites, apps, and games might not be so Orwellian after all, thanks to privacy-focused designs, there are still issues to work out. I can't say for sure whether the current biometric verification methods in combination with ZKP proofing will be enough to iron out these issues or whether a new class of solutions is needed, but I do feel one thing is certain: We need to move forward very consciously and deliberately.

Too often do we march into new technologies and 'solutions' before we've come to a consensus over the right way forward. Sometimes it feels like technology is dragging us along, rather than vice versa.

In particular, we need to ensure decisions are made in advance regarding privacy and how wide a remit we should give digital verification and IDs. These are questions that we need to answer before any such technologies are normalised. Once such technologies are in play and normalised, it can be hard to change them, or our cultural attitude towards them, at all—social media is arguably an example of this.

This problem is one I've not touched upon here, but it is worth keeping in mind: How much remit do we want digital IDs to have over our lives, and how can we ensure these technologies adhere to those limits without mission creep? If we're not conscious and deliberate and simply adopt and normalise ID technologies without pre-emptive agreement and even legislation in place, we're moving forwards thoughtlessly into an unknown future. It wouldn't be the first time, but I'm no fatalist. Let's give it a good shot.

👉Check out our list of guides👈

1. Best gaming laptop: Razer Blade 16

2. Best gaming PC: HP Omen 35L

3. Best handheld gaming PC: Lenovo Legion Go S SteamOS ed.

4. Best mini PC: Minisforum AtomMan G7 PT

5. Best VR headset: Meta Quest 3

Jacob got his hands on a gaming PC for the first time when he was about 12 years old. He swiftly realised the local PC repair store had ripped him off with his build and vowed never to let another soul build his rig again. With this vow, Jacob the hardware junkie was born. Since then, Jacob's led a double-life as part-hardware geek, part-philosophy nerd, first working as a Hardware Writer for PCGamesN in 2020, then working towards a PhD in Philosophy for a few years while freelancing on the side for sites such as TechRadar, Pocket-lint, and yours truly, PC Gamer. Eventually, he gave up the ruthless mercenary life to join the world's #1 PC Gaming site full-time. It's definitely not an ego thing, he assures us.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.