PC Gamer plays: Control, Endless Legend, The Last Day of June, and Unavowed

A spooky house and an outbreak of demons.

Every month in PC Gamer UK magazine we run a section of the games that we've been playing recently. Some are new(ish), like Control, others are old(ish), like Endless Legend. Some are awesome indie adventure games that more people should play, like Unavowed.

Discovering a surprising cinematic influence in Control—Andy Kelly

The setting for Remedy’s new shooter is the Oldest House, a monolithic, windowless skyscraper in downtown Manhattan that serves as the HQ of the Federal Bureau of Control. This is a severely warped place where the natural laws of physics, space, and time do not apply, and it’s one of the most interesting places I’ve ever explored in a game.

If you’ve ever watched a classic James Bond movie, you’ve probably admired the set designs of the late, great Ken Adam. This legendary production designer was doing such incredible work on Bond, including Dr No’s Caribbean island lair, that Stanley Kubrick poached him to design the war room for Cold War satire Dr Strangelove.

I’ve been a fan of Ken Adam for years, and as I was playing Control I couldn’t help but think of his stark, modernist sets—and when I tweeted about it, I was delighted when Control’s world design director, Stuart MacDonald, replied and confirmed that he was a fan of Adam too. He also noted that, like Adam, he’s a trained architect, which explains both artists’ talent for creating interesting spaces.

The fact that the Oldest House is seemingly frozen in the 1960s, with reel-to-reel tape machines, wood panelling, and rotary phones, is part of the Ken Adam feel, because this is the era when he produced his most famous work. A document you can pick up in Control explains that modern technology has a habit of breaking when it enters the bureau, which of course gives Remedy an excuse to give the game a cool, retro, Mad Men aesthetic. But it goes deeper than that. Every Ken Adam set is a grand place of power. Whether it’s Fort Knox in Goldfinger or Drax’s space station in Moonraker, his creations are vast and dramatic. And I feel the same playing Control. The sprawling corridors, cavernous chambers, and brutalist architecture create a similar sense of scale.

The Oldest House is a terrifying, mind-bending, illogical place, and the world design reinforces this. It’s unsettling too, with bodies hovering mysteriously in mid-air, rows of abandoned desks, and architecture that makes no sense.

And the fact that it’s influenced by one of history’s greatest production designers helps too. Videogames tapping into movies for inspiration is nothing new, but it always seems to be the same handful of sources: Blade Runner, Apocalypse Now, Heat. I’m forever seeing the same visual elements in games being pulled from a surprisingly small number of films.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

So it’s nice to see a game that looks a bit further afield when it comes to designing its world. It’s amazing that something as weird as Control even exists, but I love that Remedy was given the chance to go wild creatively, otherwise I might never have gotten the opportunity to spend time in a place as beautifully bizarre as the Oldest House.

Crunching the numbers in Endless Legend—Robin Valentine

There’s something intoxicating to me about Amplitude Studios’ games. Its Endless series—three 4X games all taking place in a sprawling shared setting—are given an incredible amount of life by gorgeous art and animation, imaginative writing, and a wonderfully creative approach to crafting sci-fi and fantasy cultures.

I’m helpless before such evocative world-building. I pick up every Amplitude game on launch, and any time I see even a whisper of DLC, it’s seconds before I’ve got it in my cart. But the truth is, I don’t actually like playing any of them very much.

After five years of DLC and free updates, science-fantasy entry Endless Legend leaves me spoilt for choice when it comes to picking my empire. There’s the tribal Kapaku, who seek to turn the world into a paradise... of volcanos and lava. Or the Morgawr, mutants who manipulate and corrupt lesser beings from their coastal fortresses. Or the Mykara, a fungal hive-entity that spreads infestations instead of cities. But as I boot it up for yet another attempt to even finish a match, I know that, whichever one I choose, I’ll feel just as dissatisfied as ever. The problem is, while so much of the game invites me to simply explore everything the planet Auriga has to offer—to the point that each faction even has its own story quests—at its core it’s as ruthlessly mechanical a 4X as you’ll come across.

All that beautiful presentation is just decoration, really. Your empire isn’t an alien culture in need of rule, it’s an engine of numbers that must be tuned until it purrs a song of cold efficiency. The world isn’t a playground, it’s layer after layer of interlocking systems, all demanding mastery. Even on low difficulties, I find myself making decisions on turn one that are revealed to have utterly crippled my options by turn 40. Rare moments of success feel like solving a difficult equation, not leading a nation to supremacy.

It’s not the game’s fault—by any metric, Endless Legend and its siblings are all extremely finely crafted, and I’m sure to players of a more mathematical mindset they’re a joy to tinker with. But they leave me cold. Frosty enough to never find the fun in them, and yet not sufficiently warned off to ever prevent me from buying in again next time, helpless to their siren song.

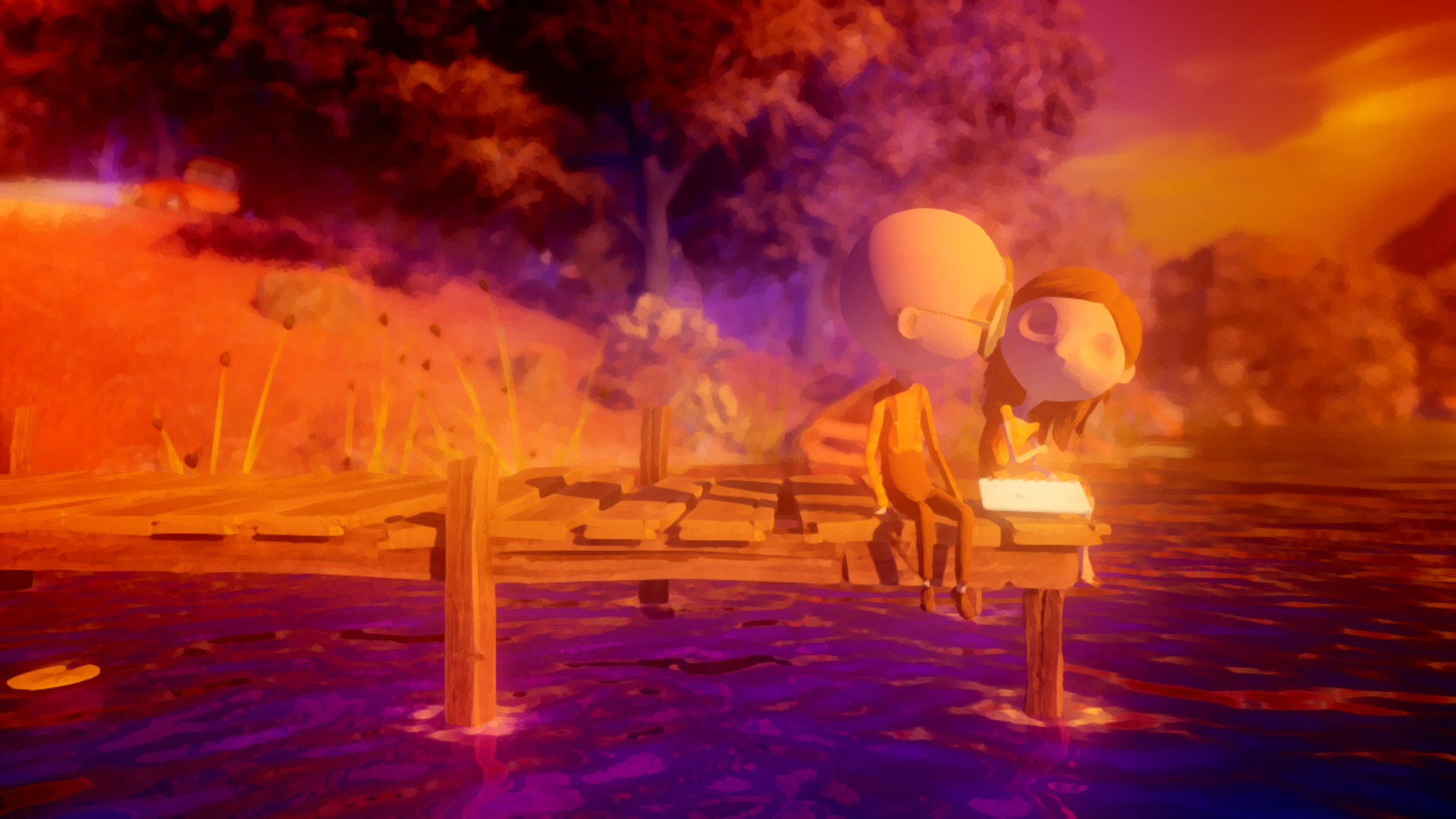

Learning to let go in The Last Day of June—Joanna Nelius

Everyone is too busy to play with me, so I run from house to house kicking my football into these huge green flowerpots, laughing gleefully as they tip over. The old man who set them up is rightfully annoyed, but eventually he takes a break from his work to help me fly a kite. Then the scene fades away to a ghost-like image of the same boy in the middle of a rain-soaked road, picking up his football. The boy dissolves into the raindrops as a car passes by, and then the scene changes again. I am now the man, Carl, driving that car, abruptly waking up from a deep sleep in my living room. I look to my right and see an empty armchair. I look to my left and see my wheelchair. Then I realise my wife, June, is still dead.

In The Last Day of June, I try to change the past through a series of puzzles, constantly tweaking a complicated timeline of events in the hope that I can bring my deceased wife back. It’s a game I’ve wanted to play since it came out, but like a lot of similar emotionally- charged games, I don’t get around to it until there’s some personal life event that calls for it; a game about love and loss is particularly cathartic for me at the moment.

By interacting with a series of paintings in your home, you travel back in time and assume the role of different characters, all of whom cross paths with you and your wife on that fateful day.

The further you progress in the game, the more complicated the puzzles become, and you see how intertwined every small, seemingly inconsequential thing really is.

Each time you wake up and discover you didn’t change the present. You do this over and over again, and while it does become repetitive, it drives home a worthy point: trying to change the past is futile, but when we are so emotionally connected to a traumatic event, we replay it in our minds as if we’ll come to some magical revelation about something we haven’t figured out yet. If we can understand what happened, maybe we can move on.

The Last Day of June is about trying to move on from that pain but chasing a tiny ray of hope that you can get back what you lost.

You see it in the bubble memories you collect as the other characters, which give you insight into their personal stories. You see it as Carl when you step out from his house and explore the neighbourhood, coming across both joyful and painful memories of the years you and your wife spent together.

Every character is tragically connected with Carl and June, and you learn about their love and loss as well. You change one sequence of events for one character, and you’ve changed them for the rest. It’s a back-and-forth game of grief.

For Carl in particular, I understand his pain well.

Joining the point and click of the Unavowed—Luke Kemp

At the risk of encouraging you to sharpen your pitchforks, I’m a lapsed PC gamer. Modern setups have been too expensive for me. But recently, like the responsible father and husband that I am, I decided to splash the cash anyway. Naturally the first thing I play with this tech is something that looks like it would run on an expensive calculator.

A good point-and-click game is one of the things I missed most about PC gaming. With no new Monkey Island or Toonstruck sequel on the horizon—and no machine to play them on even if there were—I resorted to trying to pick things up by pointing at them and clicking my fingers, which rarely worked. When I encountered a seemingly insurmountable problem, I would start trying to combine random objects to find a solution. Turns out you can’t contest a child tax credit overpayment with a cuddly zebra and a fork.

The point is, I can now properly scratch that itch, which Unavowed dispels to a level of satisfaction I hadn’t imagined possible. There’s so much to love about this game, it’s frankly ridiculous. The superb pixel art, the subtle and divine soundtrack, the razor-sharp script, by turns fascinating, disturbing, and hilarious. And the puzzles, which demand I pay attention to the game’s world while remaining perfectly logical and fair. Yet somehow, I still haven’t come to what I love about the game most.

Playing Unavowed for the first time is not like slipping back into a favourite pair of old trainers. It’s like slipping back into a favourite pair of old trainers that somebody has cleaned, repaired, and redesigned to look cooler than ever. This is the natural, nay, ultimate evolution of the genre. These games have always had reams of optional dialogue, but here I’m given an agency I’ve not seen from them before. A choice of playable characters, meaningfully branching dialogue, moral choices where the ‘right’ thing is never clear. God, I love this game.

So, it’s not point-and-click as I remember it. It’s better. As an added bonus, it doles out some tasty chunks of wish fulfilment. It lets me pretend I’m an actor. It also casts me as a member of a secret organisation covertly defending the world from supernatural threats.

The moment that I truly fall in love with the game is when I make my first moral choice. An accidentally-summoned demon needs dealing with. The first option is to kill it. The second is to allow it to feast on the flesh of innocent people I had slaughtered while possessed, building its strength up for a journey home. I go for option two, smiling the kind of deranged smile you usually only see on the front of tabloid newspapers. What a way to welcome me back to PC gaming.

If it’s set in space, Andy will probably write about it. He loves sci-fi, adventure games, taking screenshots, Twin Peaks, weird sims, Alien: Isolation, and anything with a good story.