The 50 most important PC games of all time

They changed how we make games, how we play games, and they changed us.

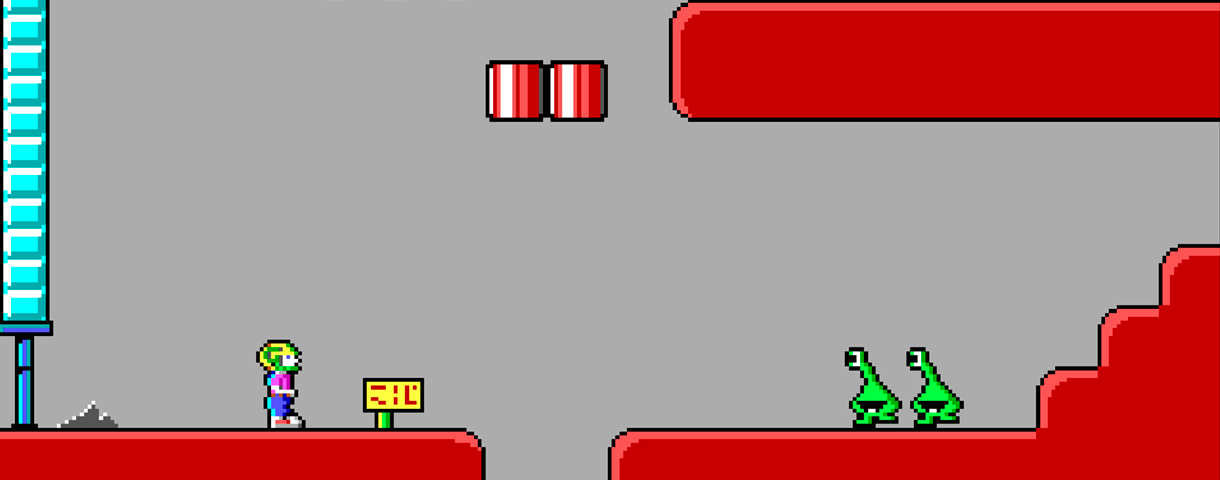

Commander Keen

Released: December 1990 | Developer: id Software

Why it's important: As well as putting id Software on the map, Commander Keen’s groundbreaking smooth scrolling hinted at a world where PCs could truly run arcade-style games. Bear in mind that at the time, people seriously put the likes of Duke Nukem 1 against Sonic and Mario. Commander Keen and his pogo stick led the way to it actually happening.

Commander Keen's breakthrough smooth scrolling on PCs was a revelation in 1990, and it's hard to believe today that the NES was then capable of things computers couldn't do. Keen was actually born out of an unofficial PC port of Super Mario Bros. 3—ironic, for me, because Commander Keen was very much my Mario. I played the sequel Goodbye, Galaxy! first, learning the basics of platforming and pick-ups and hunting down secrets.

Commander Keen wasn't my first game, but looking back it filled the same role that Mario did for so many of my console-owning friends: it was the first that really taught me the common language of gaming. Those adventures on Mars told me what a platformer was, and how to intuitively understand what I was looking at on a screen. And it taught me about shareware, a vital part of the PC scene in the early 1990s. Pretty good for a kid in a Packers helmet trying to avoid his homework. — Wes Fenlon

———

The PC didn’t have much of a culture of side scrolling games, but Keen led a brief shareware flowering. The innocent and fun tone remained a contrast to the grim and serious directions that soon dominated, and it probably stands out a little more in memories than the endless parade of military badass scenarios. — John Carmack

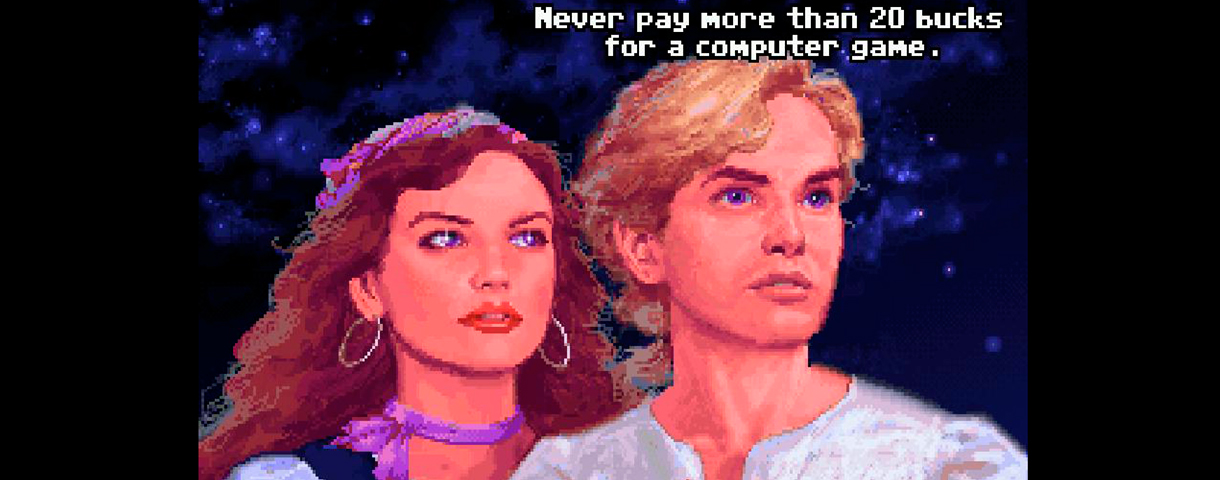

The Secret of Monkey Island

Released: October 1990 | Developer: Lucasfilm Games

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Why it's important: Not just an adventure classic, but still the template by which most adventure games are made, with its Three Trials structure to split up tasks and avoid getting stuck. It also put the boot to death as a punishment method and unfair puzzles where you could be locked out of solutions. People still did them, but they weren’t considered acceptable for long.

The “Secret of Monkey Island” was fresh and exciting for a couple of reasons. There was the humor, of course, and the LucasArts zany, light-hearted characters. But the puzzles were particularly unique. The ‘insult sword fighting’ was such a satisfying twist, because instead of actual combat, which you would expect in a video game, it was about being clever and witty and about strong writing. All the puzzles were really funny and yet had their own twisted logic. I think it’s one of my favorite adventure games, puzzle-wise, to this day. — Jane Jensen

———

The poster child for adventure games, I am not. By the time I had access to a reasonable internet connection, adventure games had already gone out of vogue. But my PC wasn’t capable of running much more than a word processor and I was stuck playing Pajama Sam and Freddy Fish on repeat. Their puzzles were no longer puzzles to me, just routine. There had to be more. Thanks to a small bout of primordial Googling, I dove deep into the adventure gaming abyss. ScummVM saved me. The first discovery was The Secret of Monkey Island. A few friends had mentioned it in passing, and I vaguely remembered a Guybrush poster on my uncle’s wall.

That game was damn near impenetrable, but I’ve never had more fun slamming my head against bad logic. I didn’t know walkthroughs were a thing yet, and spent months puzzling over rubber chickens and pulleys. I have pirate insults burned into my memory. They’ll come in handy someday, I’m sure. The dialogue was so witty and dark, the scenes so detailed and colorful, the characters were archetypes, but so easy to love—I felt like I’d stumbled onto something secret, mine, the birthplace of Freddy Fish and Pajama Sam, a personal right of passage into young adulthood. I tore through every Monkey Island, Sam and Max, Day of the Tentacle, every Scumm game I could. I pointed and clicked in my sleep. I’m still pointing, still clicking, still laughing at terrible puns. — James Davenport

Civilization

Released: 1991 | Developer: Microprose (MPS Labs)

Why it's important: Where to begin? Along with Populous, one of the defining god games, and one of gaming’s more compelling fantasies—to control all of history and mould it to your will. Some of its elements, like making palaces and seeing your cities, are still missed today.

When I first encountered it, I had never played anything like Civilization before. I came to it late, via a friend, and not long before Civilization 2 came out. I was more into games like Command and Conquer and Warcraft at the time, and Civilization looked dull by comparison. I took some convincing before I would even give it a try.

But with Civilization, I immediately realized how potentially endless the game was. I started exploring the randomly generated world, founding new cities (all of which were named after cool planets in Star Wars), and building awesome, unstoppable units like the mighty phalanx, which Civilization suggested might be a perfectly valid defensive unit all the way into the Atomic Age.

Every other game I played was finite. They had fixed missions, fixed maps. They gave you objectives and the only thing you could do was succeed or fail at them. Civilization gave you a settler at the dawn of history and said, "Go see what's out there, and what you can make of it." — Rob Zacny

Dune II

Released: January 1992 | Developer: Westwood Studios

Why it's important: The father of the RTS genre, yes, even to those who mutter about Herzog Zwei. It’s not just that almost every RTS that followed for the next few years copied it almost verbatim, with harvesters and spice analogues and resources, but that doing so felt so obvious.

It might seem odd to convert Frank Herbert's magnificent Dune universe into a top-down RTS, but remember Dune's famous adage—"he who controls the spice controls the universe". Arrakis is the only source of this mystical substance, which makes its desert plains a great setting for territorial conflict between asymmetrical powers.

In addition to the familiar houses of Atreides and Harkonnen, Westwood introduced the mercantile Ordos. The personality of each faction was expressed elegantly through unit design. The wealthy Harkonnen favour huge battle tanks while, in keeping with the novel, Atreides ally with the indigenous Fremen and wage guerilla warfare. The Ordos use gas to change enemy allegiance. Dune II didn't just establish the RTS template that would become the norm for decades, it did it with style and great respect for the source material. The rippling wormsign effect still fills me with fear for my harvesters. — Tom Senior

Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss

Released: March 1992 | Developer: Blue Sky Productions (Looking Glass Studios)

Why it's important: A technological achievement beyond almost any other game. Its 3D world, sloped surfaces, complex levels and the immersion of its dungeon environment were both unparalleled in any game, and breathtaking. Bear in mind, this was before Wolfenstein 3D.

This title screamed in out of nowhere, and did something amazing—it created a 3D fantasy FPS that few games have ever been able to match since. In fact, the deafening silence of any significant contender for years after its release made it stand out even more. The significance of Ultima Underworld is not only its visual fidelity (for its time, UU was great), but the combat, the level design, the exploration, and the narrative challenges the game presented to the player—including significant and memorable dialogues that tested you beyond simple skill checks.

The story was a bit hacky (go rescue the Baron's daughter before she's sacrificed to a demon, the Slasher of Veils), but the design elements along the way outshine the main story and still shine to this day. On narrative alone, Ultima Underworld taught me how to speak a lizardman's language, I bantered with talking doors, and after fighting all the way to the one spirit in the game who could help me with the final boss, the spirit (Garamon) simply replied "I don't know. What do you think we should do?" And I sat and stared at the screen. The game was asking me how to solve it. Initially flummoxed by this twist, I proceeded to question and volunteer ways to defeat the big baddie, and I was floored. Ultima Underworld is one of the best examples (another being Fallout 1) of how innovation can make a game excel, and I consider Ultima Underworld to be one of the best RPGs and best games of all time. And hey, if you put corn to your torch, it made popcorn. How cool is that? — Chris Avellone

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).