Military games can't pretend to be apolitical anymore without looking ridiculous

These games have always been political, but after the attack on the U.S. Capitol Building, it's going to be a lot harder for them to pretend otherwise.

Imagine releasing a game, right now, about shooting extremists on the streets of Washington D.C. and then saying, with a straight face, that the backdrop of America's capital was just a fun setting to play around with in a videogame. Imagine ending a game trailer in 2021 with the line "So, game plan: Take the Capitol back?" as a paramilitary squad geared up with tactical vests, assault rifles and grenade launchers charge a heavily fortified Capitol Building, American flag still flying over the gate.

We all know exactly what real-world events that scene would evoke today—but it was still ridiculous in 2018 when The Division 2 debuted at E3 and creative director Terry Spier said "we're definitely not making any political statements." His next line in that interview is the one that really gets me, now: "This is still a work of fiction, right?"

In 2021, that excuse is going to be pretty hard to get away with.

Games will still try to worm their way out of acknowledging the real-world politics that they draw inspiration from, but it's going to be more embarrassing than ever to watch them try. Modern warfare is the bread and butter of triple-A videogames, so much so that Call of Duty went a little into the future, and then infinitely into the future, and then came back to modern warfare in the span of a decade. Games want to play with familiar weaponry—we all know the terrorists use AKs—and familiar surroundings, because they make for widely relatable drama. Disaster movies have pulled the same trick for decades, showing us famous landmarks falling to earthquakes or geostorms.

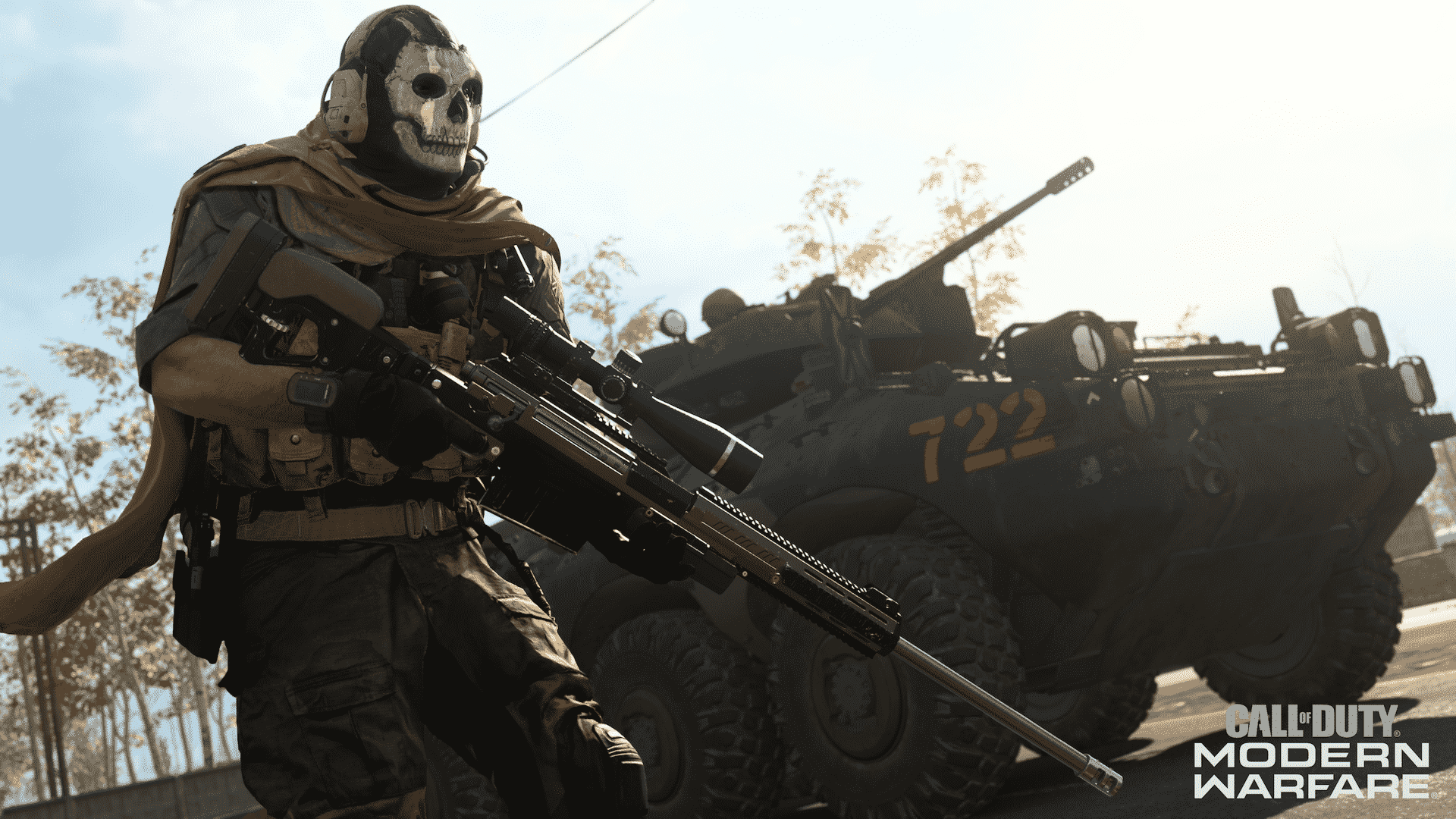

Most of today's shooters branch out from stale military gear to a more military chic style that blends civilian clothes with camo or tactical vests. Skins keep things fresh in online games, where you're seeing the same characters again and again. But it's hard to look at some of the cosmetics in games like Call of Duty: Warzone and Rainbow Six Siege and not see them reflected in the crowd that assaulted the Capitol Building on January 6th—or in the mass shooters who made the news every month before the coronavirus forced us indoors.

In the United States, this is the face of modern warfare we see on our streets. Games may not have inspired insurrectionists to show up to the U.S. Capitol wearing sneakers and kevlar helmets or tactical vests over flannel shirts, but that ultimately doesn't matter. The similarity of those hybrid civilian/military outfits is unmistakable, and it's going to be tough for games that share that aesthetic to play it off as neutral.

More scenes from yesterday's far right protest in Salem where armed supporters of President Trump watched news coverage of unrest in D.C., and called for congress to overturn election results. for @GettyImages pic.twitter.com/BSkSNcSxmIJanuary 7, 2021

Ubisoft is hardly the only big game publisher to limbo its way under the low bar of acknowledging the ideas that its games explore. But it does have an almost comical history of pretending that games like The Division and the long-running Tom Clancy series don't have any kind of political point of view. And I get it—it's a lot easier to put your fingers in your ears and make a game about sniping bad guys than it is to grapple with the fact that your game about American interventionism already makes a statement just by existing.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It may finally be good PR for big game companies to acknowledge their games are just a teensy bit political

But really, it's ludicrous to call any game with Tom Clancy's name on it apolitical—the guy's novels actually influenced President Reagan's nuclear policy in the 1980s, and years after the terrorist attacks on 9/11, Clancy said "I knew it had to be Muslims because they’re the only people in the world who think there’s something good on the other side of death."

If you read a Tom Clancy book, or learn anything about his views, it's hard not to roll your eyes when Ubisoft CEO Yves Guillemot says games like The Division 2 are politically impartial and meant "to make people think." The same goes for Call of Duty repurposing real historical events and insisting the game doesn't have a particular point of view.

Call of Duty will probably continue to do things like trot out the strangely-detailed corpse of Ronald Reagan for marketing material. But the events of 2021, a mere 14 days in, may finally force game developers to reckon with their facsimiles of the present day, if only because the events occurred closer to them. In the same vein as brands making woke social media posts about the January 6th attack on the U.S. Capitol—Coca-Cola tweeting that "what happened in Washington, D.C. is an offense to the ideal of American democracy"—perhaps the new trend in big videogames will be to acknowledge modern politics, and then do something absolutely cringeworthy with them.

Television has taken that approach for decades, gleefully ripping news from the headlines and then ham-fisting it into a fictional plot that likely misses the point. Law & Order SVU had an episode based on Grand Theft Auto 3 (the killer's legal defense, naturally, is that he played a violent videogame) in 2005 and one based on GamerGate in 2015. I caught an episode of CBS's Madam Secretary that was blatantly about the United State's real, ongoing detention and separation of immigrant families. TV drama loves to wade into a real-world crisis and solve it in a tight 42 minutes.

Videogames pull from history and modern day politics, too, but too often act like they can take inspiration while ignoring the context, like when Ubisoft depicted protesters as villains in its new mobile game, while Black Lives Matter protesters marched America's streets. TV's approach to the controversy of the day may be silly or offensive, but at least they tend to take a moral stance. They don't pretend that their characters have no opinions about the events they're living through.

It may finally be good PR for big game companies to acknowledge their games are just a teensy bit political, even if they stumble when it comes to consciously expressing their worldview through design. I can already imagine the somber E3 press conference introduction followed by the action montage—where you play a freedom fighter, not a soldier! At least bad politics would be something new to talk about, after years of dodging the subject.

Death Stranding was our game of the year last year because it felt of the moment. It looked at politics and human relationships and used those ideas to form its setting, then directly tied its themes to what you do in the game. No one has to ask if Death Stranding is political because it so clearly has a strong perspective, even if you strip away the weird radar babies and funny names. And it still has radar babies and funny names—you can absolutely be ridiculous and say something about how we connect to one another at the same time.

No matter what their developers say, games will continue to be judged as political creations, for both what they choose to include and what they choose to omit. In ways it's probably hard for us to see today, it'll be obvious in 20 years what games were made during the Trump presidency, and in the wake of Covid-19, and in the brief window remaining before climate change becomes an unignorable global crisis. These things all shape the culture that games are currently being made in. The games that acknowledge that will be the ones actually worth talking about.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).