Microsoft threw a datacenter into the ocean and it worked out splendidly

For the past two year, Microsoft has been testing an underwater datacenter.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

For the past two years, Microsoft has been operating an underwater datacenter submerged 117 feet deep beneath the water surrounding the Orkney Islands in Scotland. Earlier this summer, Microsoft fished it out, cleaned off the sea scum, and declared the project a resounding success. As it turns out, underwater datacenters are way more reliable than ones on land.

At least that was the case during this two-year trial. The concept was first proposed to Microsoft in 2014 during Think Week, an event where employees congregate to share and propose new ideas, no matter how wild or seemingly crazy. Then in 2015, Microsoft's Project Natick team proved that an underwater datacenter was perhaps not wild at all, but feasible, by deploying one in the ocean for over three months.

That moment served as a proof of concept, and Microsoft began work on a bigger test. It tapped Naval Group and its subsidiary Naval Energies to build the datacenter that would go into the ocean in 2018, which is dubbed Northern Isles.

The obvious benefit of dunking a datacenter into the ocean is natural cooling. Datacenters run hot—very hot—and it can be both challenging and expensive to keep them cool. The ocean is like the ultimate liquid cooling setup (the heat-exchanging plumbing in this datacenter is similar to what's found on submarines), though that is not the only benefit.

Before submerging the datacenter, Microsoft filled the 40-foot pod with dry nitrogen, because the atmosphere of nitrogen is less corrosive than oxygen. Microsoft hypothesized this would prove advantageous over land-based datacenters. Having it underwater would also eliminate failures from engineers bumping into cables and components when servicing the racks.

It turns out Microsoft was on to something.

"Our failure rate in the water is one-eighth of what we see on land," said Ben Cutler, who leads Project Natick. "I have an economic model that says if I lose so many servers per unit of time, I’m at least at parity with land. We are considerably better than that."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

There are other benefits as well. This approach can provide coastal populations with much faster access to cloud services, including video, gaming, and regular ol' web surfing. And in this particular instance, the power grid on the Orkney Islands is supplied completely by wind, solar, and experimental green energy technologies, so it's a win all the way around.

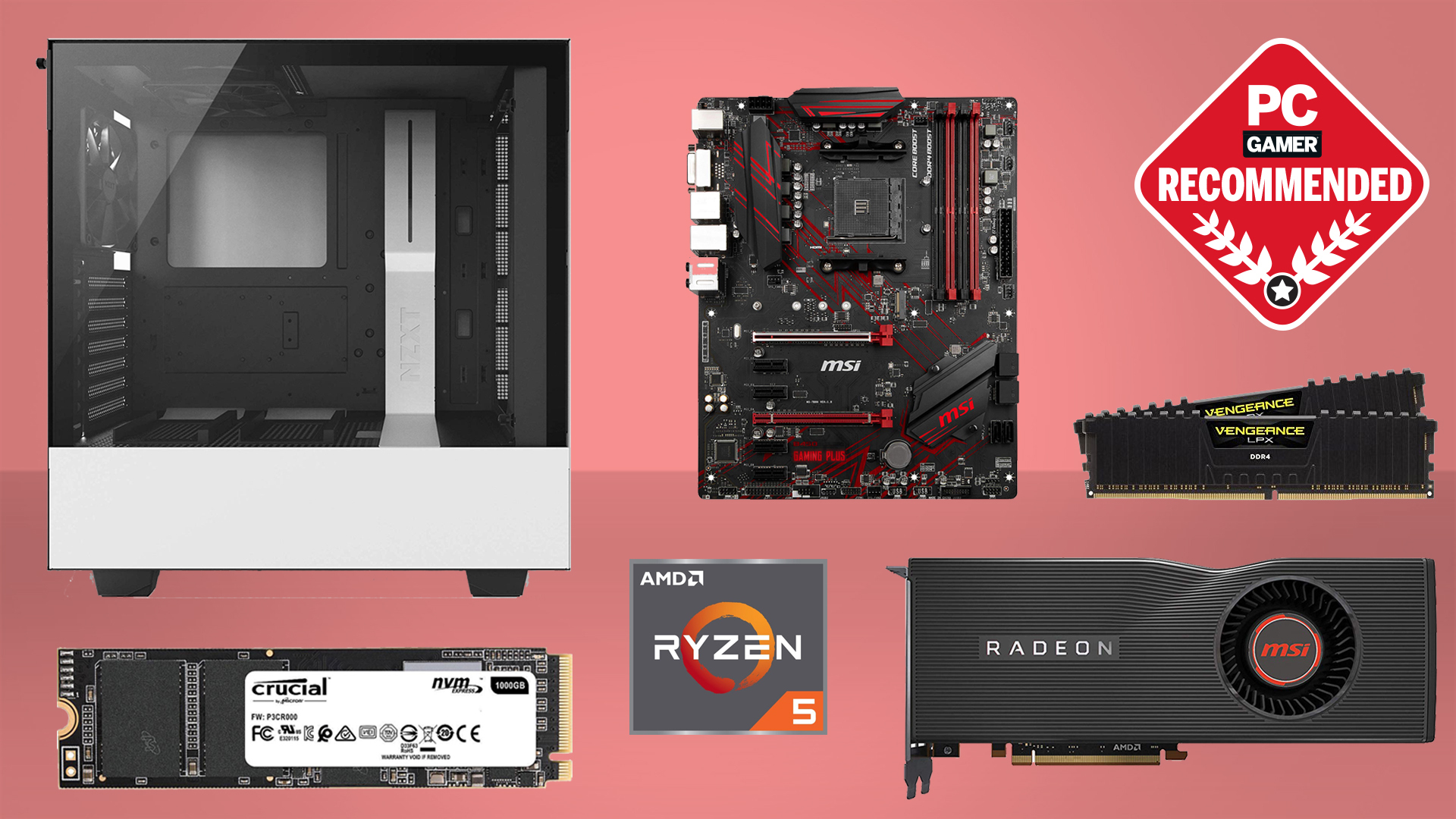

Best CPU for gaming: the top chips from Intel and AMD

Best graphics card: your perfect pixel-pusher awaits

Best SSD for gaming: get into the game ahead of the rest

What about servicing the racks when they do fail? Because the failure rate is so comparatively low to land-based datacenters, Microsoft's thought is to simply swap out all the servers every five years rather than bother with ongoing maintenance, and turn off any servers that might go bad in the meantime.

A single-pod test is one thing. Having proved their is merit to the concept, Microsoft's next challenge is to expand the datacenter's capabilities.

"Early conversations about the potential future of Project Natick centered on how to scale up underwater datacenters to power the full suite of Microsoft Azure cloud services, which may require linking together a dozen or more vessels the size of the Northern Isles," Microsoft said.

Paul has been playing PC games and raking his knuckles on computer hardware since the Commodore 64. He does not have any tattoos, but thinks it would be cool to get one that reads LOAD"*",8,1. In his off time, he rides motorcycles and wrestles alligators (only one of those is true).