Let's talk about politics in games

Buckle up, we're about to dive into the role politics plays in games and games coverage.

Every year games give us more detailed societies to explore. They show competing value systems (Ryan vs Atlas in BioShock), systems of social order (every alien faction in the Mass Effect universe), and even let us simulate our own presidential run (The Political Machine). And that’s before you start to look at games with more overt political themes like Papers, Please and Democracy.

Over the years we've noticed that any mention of politics in relation to gaming produces a divisive reaction. A lot of readers find it interesting, but plenty of others react with fury (the phrase "shoved down my throat" appears a lot). At PC Gamer we consider the political aspects of games as part of our broad coverage of games: this examination of prejudice in Deus Ex: Mankind Divided is just one example. But we realised that we've never explicitly discussed the role of politics in games and games coverage, and why we think this stuff is worth paying attention to in the first place.

So, Tyler, Wes, and Tom sat down here to to just that.

It's telling what is considered political and what's 'just part of the game.'

Tyler Wilde, executive editor: There's a conception that games are devoid of 'real' cultural significance (they're 'just games') and shouldn't be taken seriously, but the opposite is true—the everyday is far more important than the extraordinary. If you were to dissect Charles Dickens' novels and say, 'too bad these popular 19th century English novels tell us nothing about 19th century English culture or politics,' you'd surely be missing something. The stuff produced by a studio, person, country, or era necessarily reflects the time in which it was made.

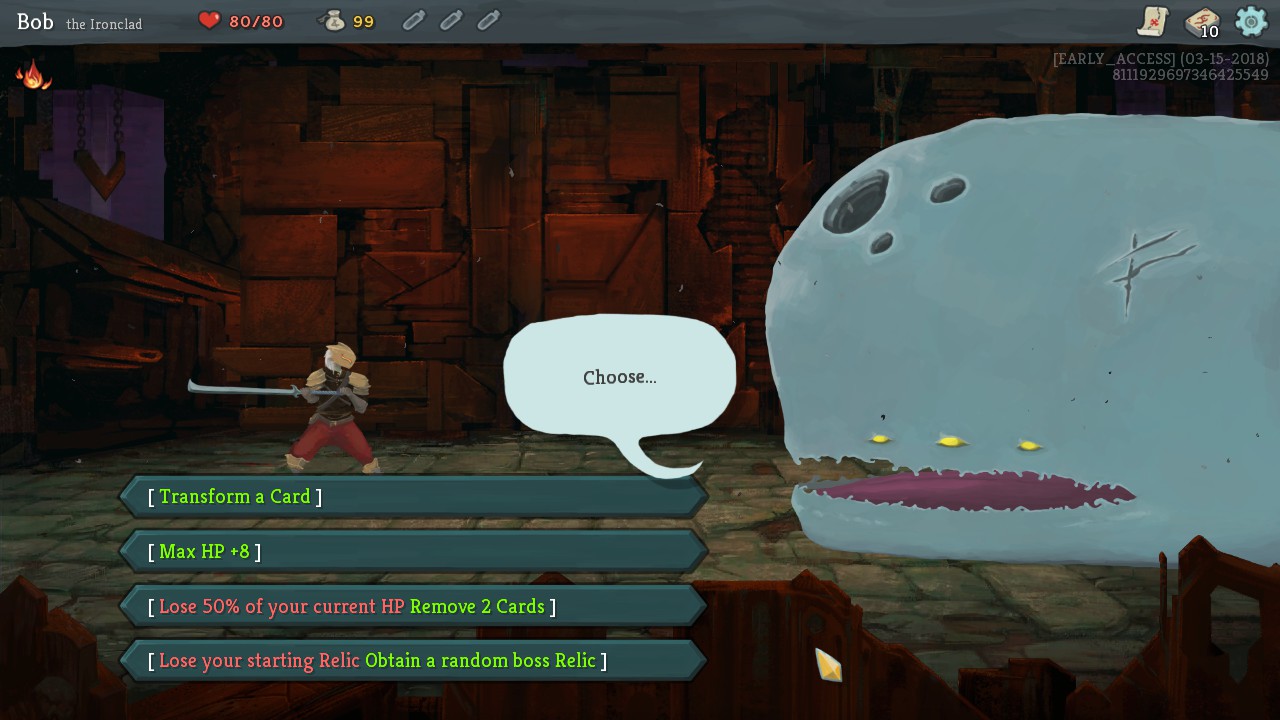

Tom Senior, web editor: I think you're right about the lasting perception that games are toys, and therefore don't carry meaning in the same way as a film or a novel. In some cases this might be true. It's hard to draw any political themes or commentary out of my current obsession, Slay the Spire, a game about playing cards to beat the crap out of goblins.

Tyler: It's possible to find meaning in stuff that, on the surface, is mundane, and I'm certain we can find meaning even in beating the crap out of goblins. I mean, for starters, the fantasy genre popularized within 19th and 20th century colonial powers (namely England) often pits human or human-like 'races' against evil, inhuman 'races'—which there is an obvious political quality to, if you ask me. Read The Princess and the Goblin, which inspired Tolkien's goblins and most after, and you'll find it is not politically inert at all. Now, I imagine Slay the Spire just wanted to throw some scary fantasy monsters at us, but in answering the question, 'what could be political about beating up goblins,' I could probably expand forever.

Wes Fenlon, features editor: I'll be honest: when I play a game with goblins, I'm not really thinking about their socioeconomic status or why humans are beating them up. That goes for a lot of people looking for escapism in games, I think: we're not all deep thinkers like you, Tyler. But you make a great point: when someone labels something as 'just a game,' they willfully ignore the history behind that game's themes. That history was shaped by culture and politics. Even if the developers of the game were oblivious to that history when they made it, it's still there! And I'd much rather PC Gamer be a publication that can make jokes about Geralt in a bathtub and also think games are culturally significant. The alternative would be so boring!

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

There is no message from the creator. Marketability and business come Number One. What happens to the future of children who use such products as their textbooks?

—Hideo Kojima

Tyler: Geralt in a bathtub is deeply political. OK, but really: what about games with more explicit political messages?

Tom: There's a distinction to be made between games that passively express political ideas in their worlds without passing comment or turning them into an explicit message—The Witcher 3, for example—and games that do. BioShock's literary influences are obvious and showing a Randian society as a warped hellscape is a clear political position. GTA and Red Dead Redemption are on a mission to explore American identity and pop culture through drama and parody.

Far Cry 5 gestured at being a BioShock or a GTA, and so the lack of any coherent point of view in the game ended up being a surprise worthy of a mention in our review. One of the ways we approach evaluating a game is to consider how successful it is at what it set out to do. If customers saw Far Cry 5's marketing and bought it anticipating some political ideas, it’s worth pointing out the absence of that, without holding that against the amount of fun you're likely to have with the game.

Tyler: Steering back to my original point again, it's telling to me what is considered political and what's 'just part of the game.' We've talked lots about the cult in Far Cry 5, but what of the cop running around shooting everyone, or how the Far Cry series reproduces narratives about rural and colonized parts of the world, or why it was deemed significant that Far Cry 5 was set in the US? Far Cry 4 includes a CIA agent meddling in a revolution and I heard a lot less talk about 'politics' surrounding it.

Wes: Metal Gear Solid is another great example of what you're talking about. I think most people love MGS for the stealth or the wacky bosses or Snake's gravely voice. But they're also some of the few big budget games that are overtly trying to say something about war, government, information, technology, media and politics—granted, the presentation is often convoluted and ridiculous and comes hand-in-hand with amateurish boob jokes, but it's still a huge part of Metal Gear Solid's identity.

Tyler: It's harder to interpret than goblins.

Wes: Here's a quote from column Hideo Kojima wrote during the development of MGS3, in 2003: "When we were kids there was still a strong anti-nuke movement worldwide. How about now, in the 21st Century? There is no such movement anywhere—even in an age when the use of such weapons worries the world ... Many players of MGS2 complain that the game is too preachy. But nowadays we cannot expect movies like [Planet of the] Apes from Hollywood or Manga like Barefoot Gen (about the tragedy of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima) which is why I would like to keep on including the anti-war and anti-nuke messages as much as possible. At least with MGS. The current entertainment industry is too merchandising-oriented. This holds true with film, books, and music. Creating products that will sell. There is no message from the creator. Marketability and business come Number One. What happens to the future of children who use such products as their textbooks?"

Tyler: He's got some points.

Tom: Lots of politics happening in games then, which is worth examining and writing about. But inevitably when a writer starts critically discussing political issues they bring their personal worldview to bear. It's impossible to be truly objective in these matters. In the UK the BBC is in a quandary because it obsessively strives for balance, and it does this by providing a counter perspective to every position in a discussion. In a debate about the Earth being round there needs to be someone in the segment saying it’s not, and the two are raised to equivalence in the debate despite the vast weight of evidence and consensus behind one of those perspectives (don't @ me).

This is relevant to our discussion, though. We’re not the BBC, but if we’re going to analyse the political content of games shouldn’t we commission analysis from, say, liberal and conservative positions, and provide a broad range of perspectives from all over the political spectrum?

Tyler: The idea that politics equates to 'liberals and conservatives arguing' is bogus, and a truly broad range would include the Maoist perspective, and the anarcho-syndicalist perspective, and so on—we'd need a thousand takes on any topic. We rarely engage that deeply with political theory, as we haven't set out to be theorists, and are not an academic publication. But I'm still critical of what we do and don't discuss with regards to politics, and how we discuss it, and who discusses it.

So is everyone else here, and we certainly aren't a monolith. I know my political views don't perfectly align with Wes' or Tom's, and theirs probably don't align perfectly with each other's. So there's going to be some pushing and pulling. But to answer the question, I want to publish good analysis. If an analysis is ahistorical, unscientific, cruel, or otherwise noxious to me, then I'm going to call that out. Of course that necessarily comes from my point of view, and I'm going to be wrong sometimes (I have been very wrong before), but I don't see that as a reason to publish whatever opinion comes our way, just because it exists.

I think you can have both the analysis and the escapism.

Wes: What's more important to me is pushing back against the idea that games shouldn't be political, and the anger and hate developers get for caring about issues like diversity and representation. It's a shitty attempt by some people to narrowly define what games are or should be because they're personally uncomfortable with the world changing. They want games to purely be an escape, not something that challenges their worldview. The good news is that they can be both of those things.

Tyler: And as I keep harping on, so much politics goes undiscussed almost entirely, which is in part our fault. For example, in mainstream arguments it mattered 'politically' who you could have sex with in Mass Effect: Andromeda, yet it did not particularly matter that it starred a private soldier colonizing a galaxy, or that it included a friendly nod to SpaceX, which is helping the United States launch spy satellites. We champion representation, which is good, but often engage uncritically with things that harm the very people sought to be better represented. That's common across all popular media. Superheroes work with the CIA, for instance, yet that is not what is usually meant when people talk about the 'politics' of Marvel films.

Tom: Wes, you referenced one of the perspectives I see a lot, that discussing politics in games spoils their escapist qualities. You might get home from work and want to boot up a Civ or Total War campaign without having to grapple with knotty questions about how religions and historical factions are presented, or something—the game is there to entertain for a while. I think sometimes criticising representation comes across to some people as saying “you’re not allowed to like this anymore,” but that’s never the intention. For me I could read some analysis about that and find it interesting, and then lose myself for hours in a campaign regardless because I fuckin’ love Civ and Total War. I think you can have both the analysis and the escapism.

There is something to be said for games as an apolitical space, though. Games, like sports, can be a place where people with very different views can come together and find common ground. As politics becomes more polarised these shared experiences seem more valuable to me as a way of bringing people from lots of places together to kill a raid boss, or wipe the enemy team in Rainbow Six Siege. Team-based games give us the opportunity to experience moments of chemistry and bonding with people we might otherwise not get along with.

Tyler: 'Escapism' itself has political implications (what are you escaping from?), and the act of creating a game also relates to politics. You can't get away from it, but you can of course play games uncritically. I'm not thinking about fossil fuels while grabbing boost in Rocket League. I'm just playing some Rocket League because I'm tired and the day sucked and I want to tune out. How could I judge anyone for doing the same?

Wes: I'm generalizing here, but I feel like far more people get up in arms about LGBTQ characters being "forced" into games than they do Metal Gear Solid taking a political stance.

Tyler: Right, which illustrates how the distinction between what is 'political' and what is 'apolitical' is an illusion. How can it be that CS:GO, where you play as terrorists or counter-terrorists trying to plant or defuse a bomb, is viewed by many as apolitical, while any game that happens to feature a queer character—something far more ordinary—is branded as political or simply 'SJW?' The answer is that the actual purpose of calling a game political is to categorize other games as apolitical, and that is done to support certain, often unacknowledged, worldviews, such as that 'The War on Terror' is undebatable, correct, moral, while the personhood of certain people is debatable, political. That's a really twisted view to me. I think about that whenever someone says we've got to 'get politics out of games' and then hops into CS:GO or whatever—how can one imagine that 'fighting terrorists' has no political quality, that it's meaningless?

There's a lot more to discuss about politics and games—we haven't touched on labor rights, copyright law, censorship, and so on—but we hope this brief chat has helped shine a little light on how we interpret and write about the political messages games deliver (whether they intend to or not!). We invite you to discuss the role of politics in games and games criticism in the comments, but because it's a heated topic, do make sure you're following our community rules. As always, we'll close threads that don't meet our standards.

Part of the UK team, Tom was with PC Gamer at the very beginning of the website's launch—first as a news writer, and then as online editor until his departure in 2020. His specialties are strategy games, action RPGs, hack ‘n slash games, digital card games… basically anything that he can fit on a hard drive. His final boss form is Deckard Cain.