How Deus Ex: Mankind Divided nails the personal side of prejudice

What Eidos Montreal's latest got right.

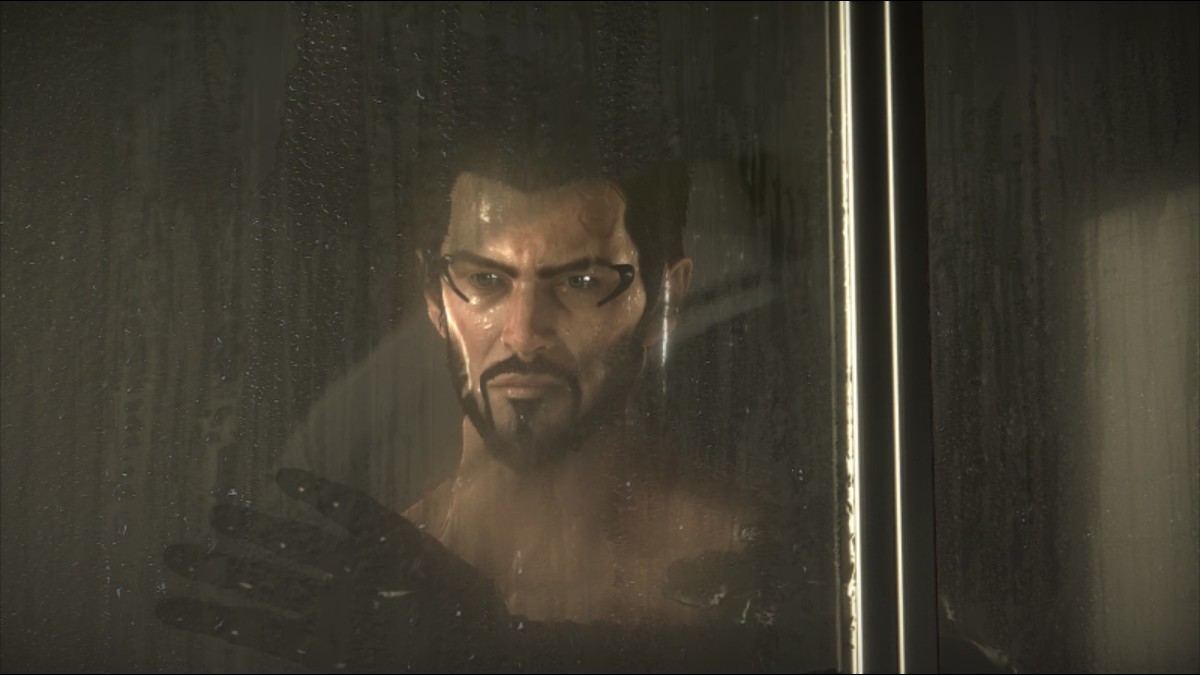

I've spent the past five years of my life living in countries where my skin color marked me as a target of fear and hostility. People ran screaming from an elevator upon seeing that I occupied it, on two separate occasions, in my apartment building in South Korea. I've been turned away from restaurants, watched people run across traffic-filled streets to avoid being on the same sidewalk as me, and noticed mothers pulling their children closer in response to my simple presence...just like the wary woman eying suave Interpol agent and Deus Ex protagonist Adam Jensen in the picture above this paragraph.

I say all of this at the start of an article for a site about videogames, reluctantly, because it may explain why I see incredible nuance in Deus Ex: Mankind Divided. Despite being the game to use the infamous marketing campaign of 'mechanical apartheid', in practice, Deus Ex: Mankind Divided treats human prejudice with a sense of the personal typically understood only by those who have lived it.

After an action-packed tutorial, you spend the next fifteen minutes of the game's opening watching a montage showcasing the state of Mankind Divided's world, listening in on a conversation between the Illuminati, and inhabiting an in-engine cutscene where you meet a friend on a train station platform—a seemingly odd approach for an immersive sim. This is, after all, a genre that relies on an absurd degree of player control. Why take this control away for such a significant period of time, just as the player is adapting to the systems and core exploration loop of the game?

This sequence offers a fascinating insight into the design philosophies underlying the entire game. The key to what I believe to be one of the most human portraits of prejudice in all games. You aren't just observing the melodrama of harassment, happening to a sympathetic series of faceless third parties. You have to play it.

In the world of Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, a recent catastrophic incident caused everyone with an augmentation to malfunction, and turn violently on the people around them. Security measures worldwide increased dramatically as a result, and the added attention isn't always earned. Regardless of economic or social status; regardless if a person has an implant for practical, aesthetic, prosthetic, or work-related purposes; anyone's augmentation is now viewed as a universal, potential threat. Increasing numbers of innocent augmented people are getting stuffed into ghettos and slums, as the world considers how it wishes to treat these new liabilities.

As if things weren't already bad enough for the augmented in the world of Deus Ex, who have to take regular doses of a drug known as Neuropozyne to avoid their bodies rejecting their implants, being augmented now marks one as a target of everything from harassment to extortion.

Crucially, Adam Jensen's status as the player character does not exempt him from this new state of being. Even as a white, gravel-voiced, nigh-unstoppable, sleekly cybernetic badass who is in fact an agent of the government, he's still marked. You're still marked. The form this takes, on a systemic level, is fascinating.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

In games and game culture, the interruption of flow is treated as the greatest consequence players can face. 'Game Over' screens are an example of such an interruption, and can set back your progress to boot. Loading screen delays are detested. Cutscenes pause the action, or can just be seen as boring, causing many players to demand ways to skip them. Taking damage in a game which allows you to regenerate health forces you to take cover, temporarily putting you out of the fight. Mankind Divided directly uses this line of thought to reinforce its theme.

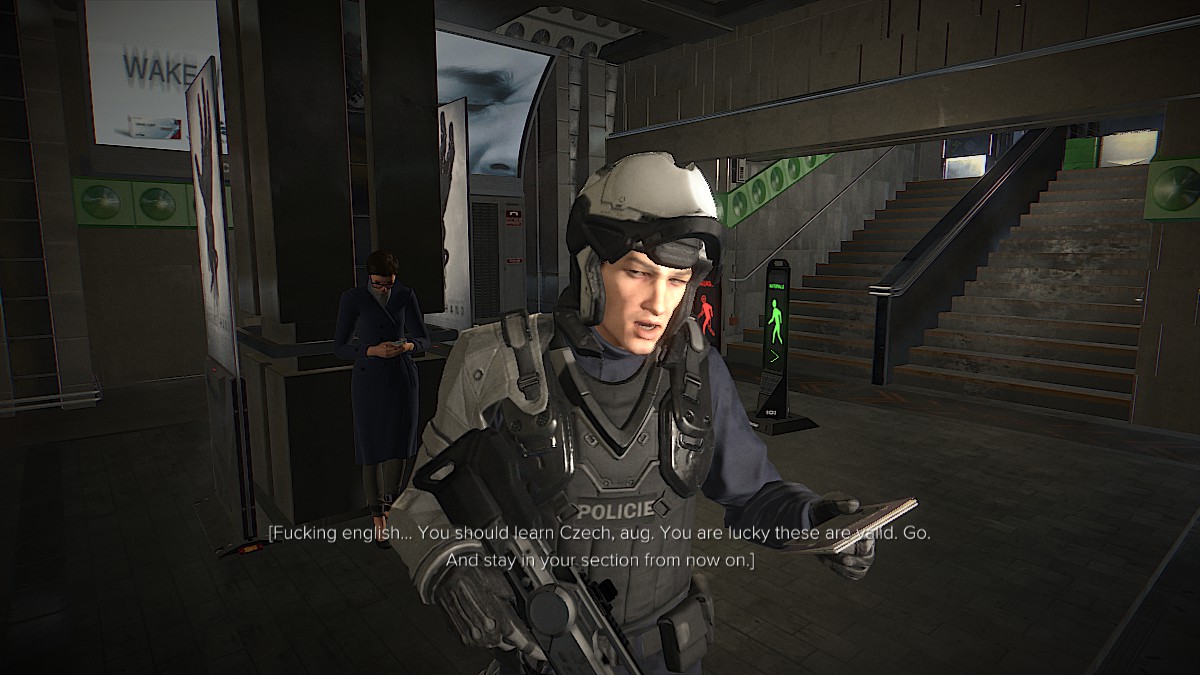

Referencing its title, the game world is split between the 'naturals' and 'augs'. When pointing you towards a mission objective, your HUD will direct you to use the aug section of the subway, causing you to pass through narrow entrances clogged with passengers being screened, mandatory document checkpoints and fences of chain and barbed wire as you go. You're Adam Jensen, though. You can disobey this suggestion, and use any part of the train you want! You can stroll through the far more convenient and clean portion of the subway reserved for 'naturals', and use touchscreens to board their reserved cars.

Upon reaching your destination, however, you will be confronted by an officer of the law—and held up while they check your paperwork until they feel you've been suitably chastised. It's uncomfortable. It goes on for far longer than it feels like it should. It's a tangible punishment communicated through a lack of interaction. A powerful enough deterrent, perhaps...to ensure that you stay in your line. Whatever you may believe about the central conflict of the game, and whether or not this is deserved.

This doesn't happen often enough to become a capital-m Message, and it isn't necessarily a story-rooted encounter either (like a confrontation with a checkpoint guard which forces you to pursue a quest to get new, supplemental paperwork, or pay an enormous bribe every time you pass through). People generally try to leave the guy with blade arms (read: you) alone as you walk the streets. It does occur just often enough, however, to grate.

You can stumble into these situations by accident. Running to the next mission location, you can zone out, end up in the wrong train car, and spend the time after a loading screen dealing with a public official with an inflated sense of power. This is just one example of how Deus Ex unobtrusively finds a way to both respect your power as a player, while simultaneously making sure you remember your place in its world. No matter how powerful you make Adam Jensen, at the end of the day, you're just another aug facing a parade of unfriendly faces.

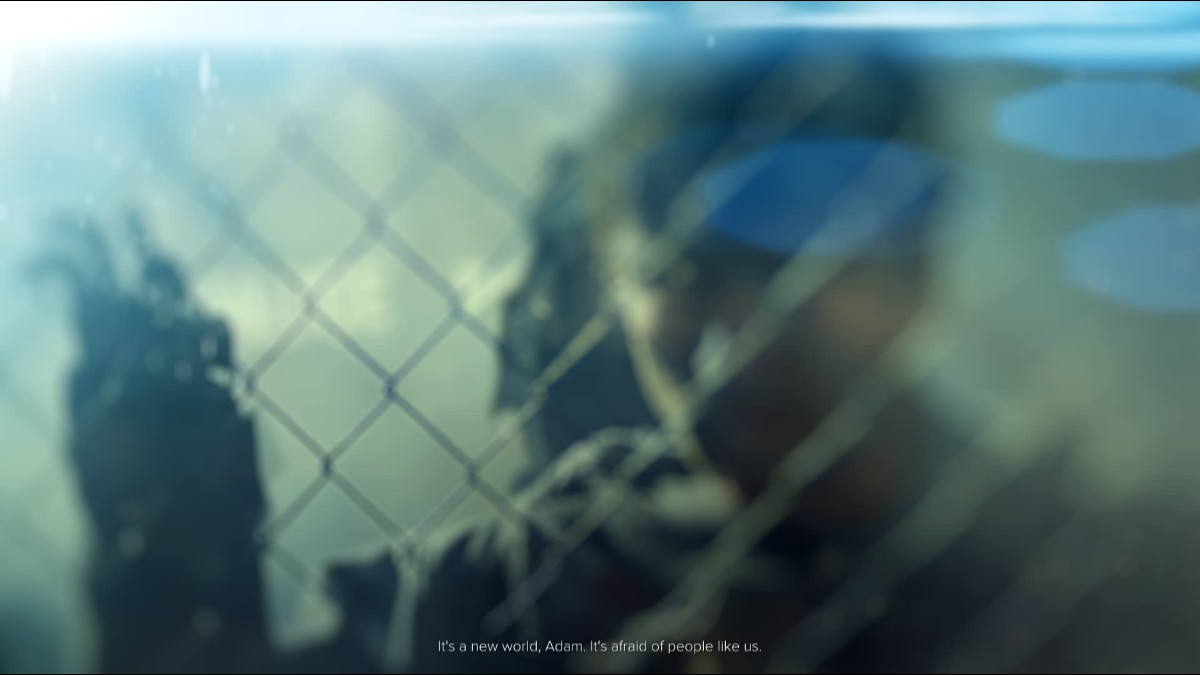

Facing the reality of lost time...

...lost patience...

...lost humanity.

Going back to the mother pulling her child closer mentioned at the beginning of this piece: media using a designated 'other' to represent minority groups and struggles is nothing new. X-Men has its mutants, Dragon Age has its treatment of elves, Skyrim's khajit serve as a Romani analogue, and so on. At its release, Mankind Divided got a lot of flak for its choice to brand augmented people, regardless of social and economic barriers, as this 'other'. I won't suggest that this criticism is completely unfounded. It's reasonable and expected to call out the specific way in which something attempts to approach an allegory for prejudice, especially in politically-charged times that are themselves referenced within the work ("Black Lives Matter" is shifted to "Aug Lives Matter" within the context of the game).

There are times within the game that the metaphor is fairly obvious, and characters function as mouthpieces for viewpoints moreso than authentic people. I do believe, however, that Mankind Divided contains a strain of genuine, subtle nuance. Little touches that can't be slapped into a flashy marketing campaign, and can pass by players fully absorbed in a haze of cyberpunk shenanigans and RPG looting. Despite the dystopian sci-fi trappings, when I play Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, I see a familiar world—but in this life, I'm not Adam Jensen.

I'm a young black kid on a train in a foreign country, keeping my head down, because I see a monster reflected in the eyes of the people around me.

A monster I think Adam Jensen knows all too well.