In between famous '80s JRPGs, Falcom made a shmup that broke all the rules

Making magic out of missiles.

Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialist '80s computers to the happy days of Windows XP.

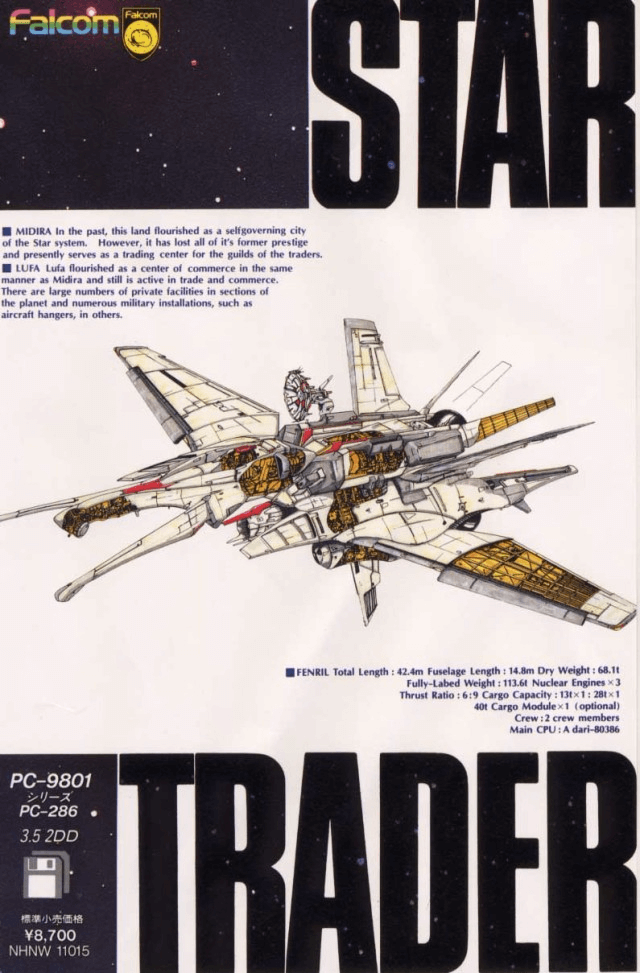

"We made 'STAR TRADER' because We were interested in exploring this theme further" states the oddly capitalized cover of the otherwise entirely Japanese manual for Falcom's 1989 adventure-shmup hybrid. No further explanation of this straightforward sentence is given—apparently Falcom thought that it was all the justification needed, even though it had spent the decade building a reputation on RPGs filled with heroes and gods and little else. At the end of the '80s Falcom wanted to do something different from Ys and Dragon Slayer, so it just did, simple as that.

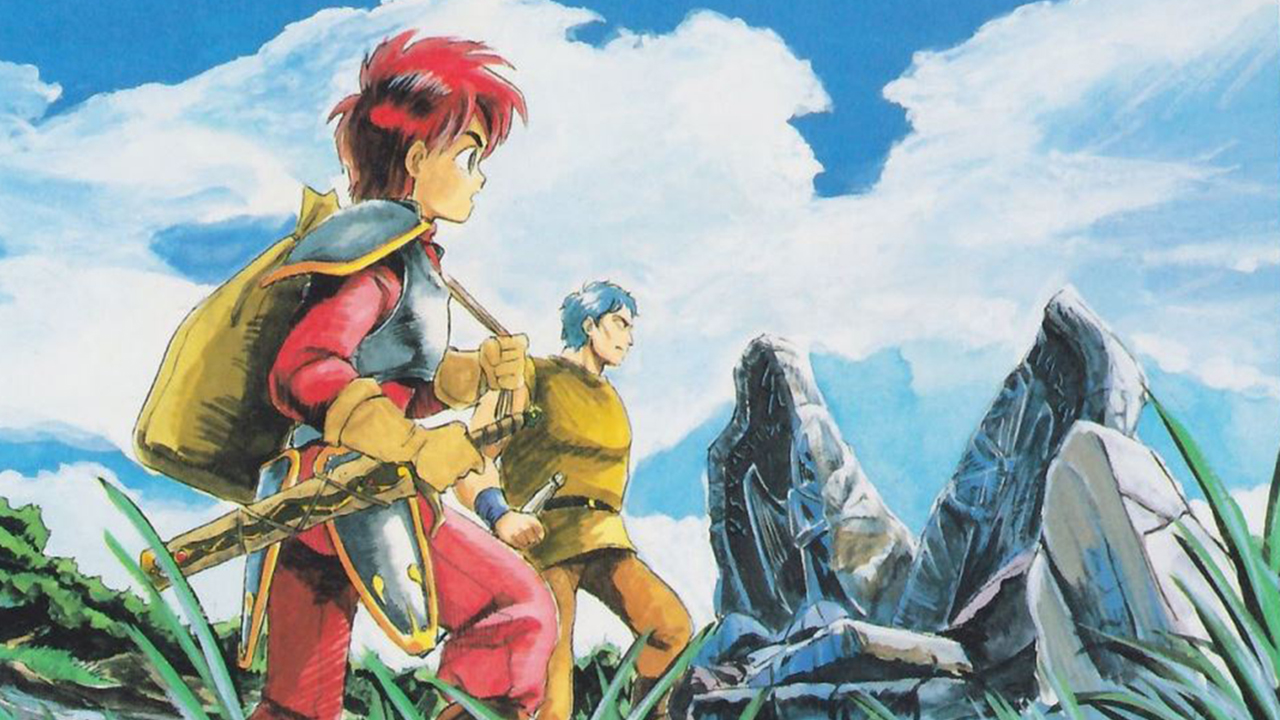

Bold creativity was part of the company's culture: Falcom pretty much invented the whole concept of action-RPGs with 1984's Dragon Slayer, and the studio's development history between then and Star Trader is littered with a diverse range of swords and sorcery series. Some are still going strong today, and almost all of them were standout successes at the time.

But how would any of that help them create a shmup that was any good, never mind stood out, during a hyper-competitive period for the genre—the same year R-Type II was making waves in arcades?

It doesn't seem like much could transfer over from Falcom's specific brand of fantasy action to a setting filled with sci-fi ships and space stations. But the truth is Ys, which debuted on Japanese computers just a few years earlier, turned out to be the perfect training ground for this one-off shmup. A bullet is just a small pixelated fireball when you get down to it, and by the late '80s Falcom had already mastered flinging those around a screen. From a certain point of view making a gigantic metal fortress spew electricity from protruding pylons isn't all that different from designing a large god/demon/monster capable of flinging a lightning spell from their hands/staff/tentacles. A sleek spaceship's power level is really just a health bar with another name.

Even though it's broadly familiar, Star Trader was an off-kilter success because of that very different creative background. It's a shmup made by a team who hadn't made a shmup, a shmup made exclusively for home computers (initially NEC's PC-88 and PC-98 in this case, with a distinct third-party port to Sharp's X68000 a few years later) rather than powerful arcade machines, and a shmup sold to people who weren't expecting a shmup from this particular developer.

It was the gaming equivalent of a popular metal band's surprise smooth jazz EP. Star Trader didn't follow the unwritten rules that already bound the better established examples of the genre.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

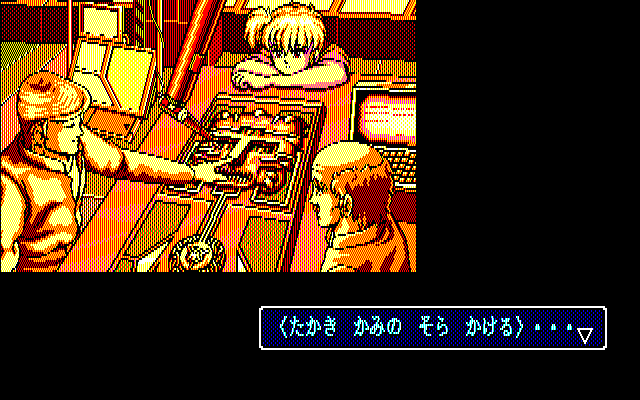

Star Trader eagerly demonstrates its independence by opening with a lengthy cutscene full of art that could've fit into any high quality adventure game from the era. Instead of then hastily cutting to the "real" game everyone came for—the shooty bit—it instead merrily carries on with a whole lot of not-shmupping business: introducing new characters, offering multiple dialogue options during numerous conversations, and letting me decide where I'm going to fly off to next. That's where the shmup part comes in, with playable space routes between locations. Unlike most shmups, Star Trader isn't limited to pre-arranged levels, and it doesn't introduce its lore and characters in the manual, to be read once and then ignored forever.

We get lots of time with the Han Solo-ish pilot Kain and the friends, enemies, and frenemies he makes along the way, and it's time well spent. They add personality and context to the action where there would have otherwise been nothing more than infinite starfields and laser beams. The stakes are higher when I'm defending space stations because I've spent time with the characters inside them, chatting while Kain leans up against a bar. Even the most impressive final boss sprite or bass-heaviest battle music couldn't deliver that extra drama.

Characters in shmups are "unnecessary" in exactly the same way adding large shopkeeper portraits to an old RPG is "unnecessary"; they have no impact on how Star Trader plays, but the world feels so much more alive and vibrant for having them.

Did you know the Japanese RPG has its roots on the PC, not consoles? Read more about it in our feature here.

Even with all of these chatty diversions to take in one dialogue box at a time there's still plenty of shmupping to be done. As with everything else Star Trader casts a questioning eye over genre tradition and happily jettisons anything it sees no use for. That includes the one thing you would expect every shmup to have: scores.

Sorcerian didn't need a scoring system to be successful, Ys didn't need a scoring system to be successful, so why should Star Trader? The best response I can come up with is to weakly insist "But shmups are supposed to have a score system!", even though I was so caught up in the action I honestly didn't miss it while I was playing.

Power-ups floating along in the depths of space are also conspicuously absent Star Trader uses equippable weapons bought in a shop using money earned by completing optional side ques—sorry, jobs—instead. And from there it keeps playing with the formula.

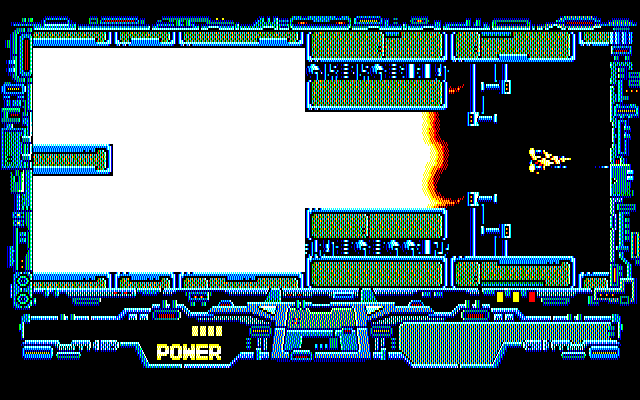

One area begins with a screen-sized boss battle, breaking pretty much every shmup rule pacing rule. Another chooses to end in a thrilling do-or-die escape sequence, the ship licked by floor-to-ceiling flames from behind as the destructible shutters ahead slam closed. I squeak through and am immediately thrown into an intense one-on-one battle against an assault ship so large it must be destroyed piece-by-piece. It's wrong. It's wrong because… because other shmups don't do that. Escape is supposed to be a reward, an end—not the breathless prelude to a massive boss. But this sequence was so memorable precisely because Falcom didn't bother to read the shmup rulebook. I was genuinely surprised by a type of game I've been playing since I was old enough to grasp an Atari's rubber-coated joysticks.

Falcom's RPG roots just keep peeking through, giving scrolling and shooting the reimagining they need to feel dramatic—cinematic, even, to make Star Trader more than Another '80s Sci-Fi Shmup. It's bursting with visual embellishments that exist solely to help players believe they're on an interstellar journey through fantastic, hostile, territory. Metallic pods peeling back like blooming flowers, forcing out a cluster of deadly missiles ahead and leaving their outer shells passively floating in space. One part of one route skims a desolate moon's surface, Star Trader never taking a second's break from the action even as this breathtaking background scrolls into view.

Despite the sci-fi skin Star Trader truly was a natural evolution of Falcom's early magic-infused RPGs and adventure games. It's a sincere attempt to combine shmups and interactive stories at a time when doing either one well was a hell of an achievement. Star Trader feels daring and subversive even today—it only could've come from a team that was just passing through the genre instead of trying to make it their company's bread and butter, and it's a great reminder that rules are made to be broken.

When baby Kerry was brought home from the hospital her hand was placed on the space bar of the family Atari 400, a small act of parental nerdery that has snowballed into a lifelong passion for gaming and the sort of freelance job her school careers advisor told her she couldn't do. She's now PC Gamer's word game expert, taking on the daily Wordle puzzle to give readers a hint each and every day. Her Wordle streak is truly mighty.

Somehow Kerry managed to get away with writing regular features on old Japanese PC games, telling today's PC gamers about some of the most fascinating and influential games of the '80s and '90s.