How fidgeting playtesters convinced Valve to drastically shorten Half-Life: Alyx's intro

It originally took "an hour to two hours" to get your first gun, says Valve. Fidgeting playtesters changed that, and more.

Having to stand still and listen to characters talk in a game can sometimes be challenging for me because the act of doing nothing is counter to my idea of playing a game. I recall several scenes in Half-Life 2 where I had to listen to Alyx, Eli Vance, Dr. Kleiner, and other characters lay out the story. There was nothing boring about what they were saying, but it was still hard to not pick up objects and start throwing them around while they talked, or to try squeezing past them through a door so I could get back to playing instead of just listening.

It's even more difficult to keep my hands to myself in VR, because in VR I actually have hands. There's an immediate and constant impulse to reach out and touch things in Half-Life: Alyx, to touch all the things, to pick them up and throw them, to move around, open doors, peer through (or break) windows, and otherwise to test the game's possibilities and boundaries.

And I'm clearly not alone. As Valve began presenting development builds of Half-Life: Alyx to playtesters in VR, they discovered something that deeply shaped the finished game.

"It's so much harder [in VR] to get players to stand still and just not do anything than it is if you're sitting at a keyboard, where it's only fingers doing the movement," level designer Dario Casalo told me. "It's just that much harder. And people, I guess they don't want to stand around and not do anything. We couldn't have predicted that until we started playtesting."

"We were also subject to players' [patience] limits, and it seemed to be a little lower [in VR]," Casali said. "The player limits and Half-Life 1 and 2 and the episodes, where they would start to get fidgety and throw cups around and kind of look in the corners and try to open doors and stuff. We had a few minutes at most in Half-Life 1 and 2.

"And I guess the players now, because they're standing up, for whatever reason that makes them more fidgety, and they have far lower tolerance to stand around and watch a scene unfold over a lot longer period of time. So, we started condensing our choreographed scenes so that they would be more punchy, they would be less vulnerable to players just sort of losing interest and focus."

We need to have more of what players really want, which is interactions

Dario Casali, level designer

Half-Life and Half-Life 2 also had extended introduction sequences. In the original there was Gordon Freeman's now-iconic tram ride and the uneventful beginning of his extremely eventful work day. In Half-Life 2 there's a long stroll through City 17, pursuit from the Metro Cops, a meeting with Alyx, and a visit to Kleiner's lab (and, briefly, Breen's office) before you get your hands on a gun or a crowbar.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Half-Life: Alyx's intro is comparatively short, but it was much longer before playtesters began fidgeting their way though it.

"I think [originally] it was an hour in, maybe more. An hour to two hours in before [they] even got the pistol," said Casali. "It was like 35 minutes of [choreographed] scenes before that point, and we were having fidgeting players. [We decided]: We need to contract this, we need to have more of what players really want, which is interactions."

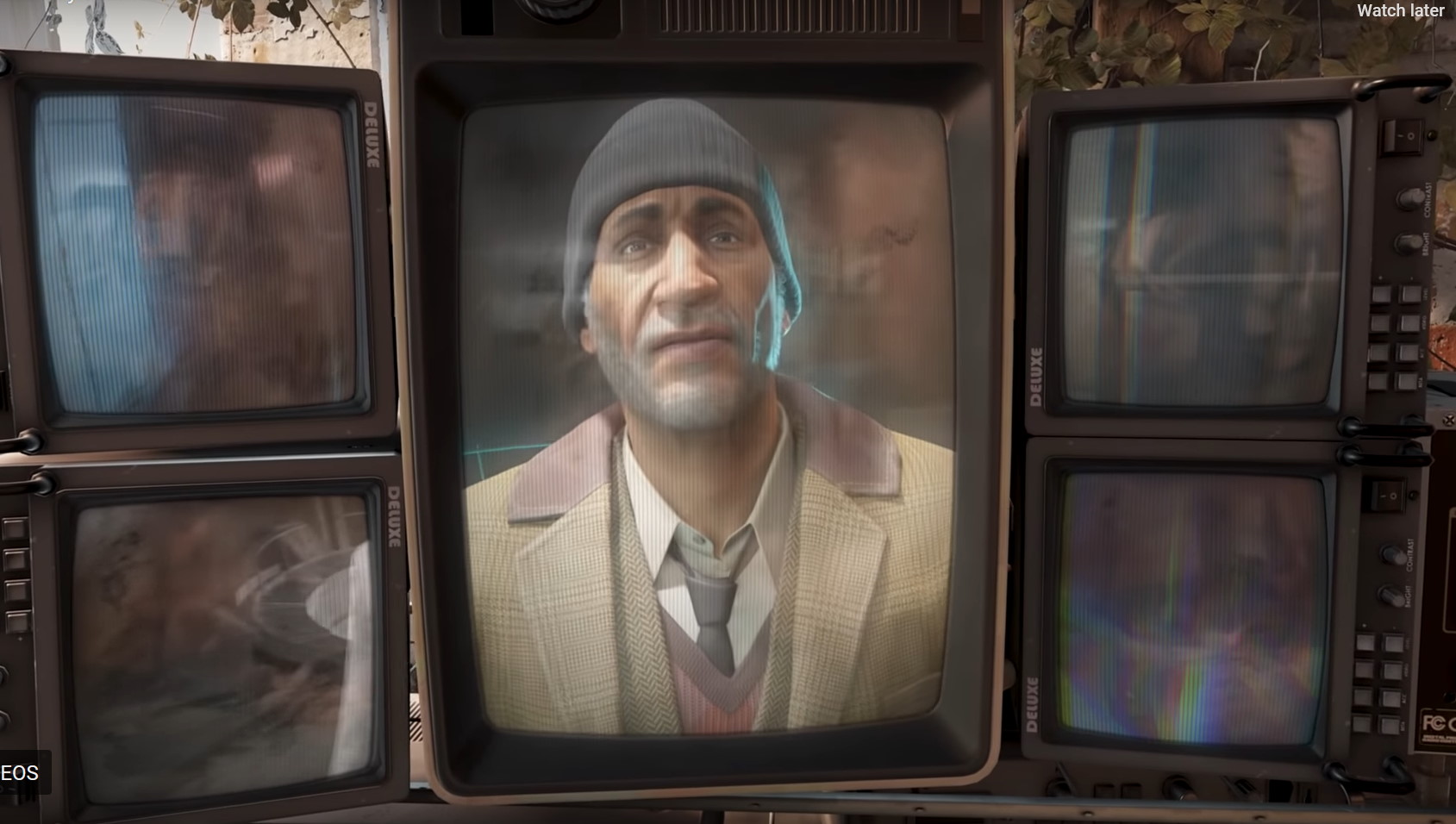

In addition to relatively shorter expository scenes, one of the things I noticed in Half-Life: Alyx that felt like a departure from the earlier Half-Life games in that you rarely come face-to-face with other characters. In the original Half-Life there are scientists and Barneys walking right up to you throughout the game, talking to you, and following you around. Half-Life 2 has multiple characters you share space with, plus lots of citizens and rebels to meet. Half-Life: Alyx has a few face-to-face meetings but in comparison to the other games it's far more solitary.

That's a shame, because there really is something fascinating about sharing space with another character in VR. The lack of face-to-face meetings are partly due to the game taking place in a quarantined area sealed off from City 17, and some is due to the fact that Russell can speak to you via headset so you don't need to be in the same room to have a conversation. But it can also be chalked up to playtesters not wanting to stand still, or simply not knowing quite where to stand while scenes were taking place.

You can walk around, you can walk right into them, and you know, put your head inside them.

Erik Wolpaw, co-writer

"Having worked closely with the choreo team," co-writer Eric Wolpaw told me, "blocking out those character scenes in VR presented some challenges. And we took more time to do each one partly because in the traditional flatscreen first-person game, if you know you're gonna interact with a character, they're going to do their thing. If the two of you collide, we can just kind of push you out of the way. And it's fairly seamless.

"In VR," Wolpaw said, "you're just going to interpenetrate [other characters] because you can walk around, you can walk right into them, and you know, put your head inside them. And it's not a huge problem, because most players will play along with their role.

"What makes it more difficult in terms of blocking everything out is you want to make it very clear to [the player] where they should be. So it's all flowing very naturally. And you don't have to be thinking about 'Where should I be now so that I'm not going to interfere with this scene?"

After having played Half-Life: Alyx I can definitely see why these decisions were made. While I didn't try to stick my head inside Russell, I sure did wander around and mess with his office a lot while he was trying to talk to me, and even though I spent a lot of time happily messing around in the intro to Half-Life: Alyx, waiting over an hour to get my fidgety, restless hands on a gun probably would have been too long.

If considering making the jump to VR, here's the best GPU and VR headset for Half-Life: Alyx.

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.