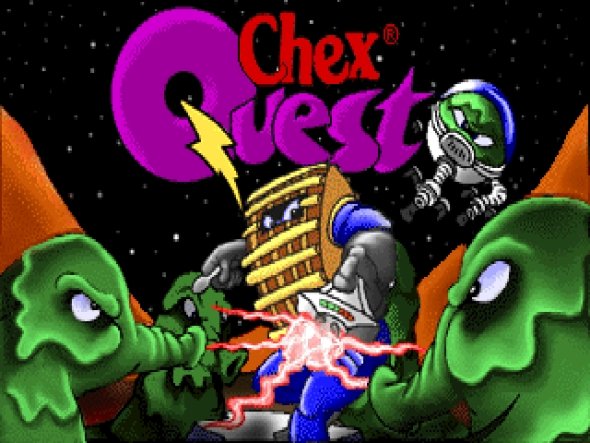

Chex Quest was gaming's best cereal-based shooter

If you reached your hand into a box of Chex cereal in 1996, you may have grasped one of the most beloved Doom mods ever made—Chex Quest, a free advergame, often bundled with a trial for America Online internet, commissioned by General Mills to associate its unsugared cereal with high-tempo intergalactic combat. To a breakfasting youth not tall enough to board the demon-ventilating Doom rollercoaster, donning the wheat-checkered armor of the Chex Warrior was a mom-friendly substitute—you weren't buckshotting Mars demons, just “zorching” anthropomorphic boogers back to their own dimension.

Chex Quest is a cherished blip in my gaming development; my cousin and I single-player co-oped (splitting the axes of movement and shooting by sharing the keyboard, I moved while he opened doors and shot) the game for hours. Your melee weapon? A spoon (that could be upgraded to a spork-tazer). Your chaingun? An electro-zapper spinning with red bolts. Healthy vegetables, fruit and water were the palette-swapped versions of armor shards and health.

Chex Quest has lived on in a handful of active fan communities (like the surprisingly active Chexquest.org) that have contributed multiplayer mods and other WADs to the base code, but also through some of the game's original creators. Encouraged by the clamoring community, Chex Quest lead artist Chuck Jacobi (who worked on Red Alert 3 and other Command & Conquer games at EA LA) released Chex Quest 3 in 2008, a pet project that recaptures the colorful camp of the original.

For Jacobi, working at a company in the early '90s that specialized in creating presentations and marketing websites for other businesses, Chex Quest was his first foray into game development. “I was a huge fan of Doom. With my co-worker Scott Holman, we made mods in our spare time as a creative release. Getting the chance to make a game was like a gift from god at the time, and Scott and I definitely steered the project toward using Doom when we learned that it could be a possibility.”

Even laden in breakfast branding (one level finds the Chex Warrior gunning Flemoids in a Chex warehouse; in the final stage, you rescue giant Cheerio men who are also space diplomats), CQ manages to emit so much charm, sure credit to the original team's ability to create lively levels, weapon animations and art, and slot them in a fun, all-ages context. “We simply put a disguise on an already excellent game,” Jacobi says.

Jacobi is right to acknowledge the Doom engine for Chex Quest's popularity—the pace of WASDing through Carmack's frictionless engine is ageless. And other than shareware, CQ was one of the rare free games available in 1996. But even knowing that, it may be the most successful advergame ever—how many marketing-inspired games today would spawn role-playing micro-communities, ill-advised fan fiction, cosplay, or piles of fan art?

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Evan's a hardcore FPS enthusiast who joined PC Gamer in 2008. After an era spent publishing reviews, news, and cover features, he now oversees editorial operations for PC Gamer worldwide, including setting policy, training, and editing stories written by the wider team. His most-played FPSes are CS:GO, Team Fortress 2, Team Fortress Classic, Rainbow Six Siege, and Arma 2. His first multiplayer FPS was Quake 2, played on serial LAN in his uncle's basement, the ideal conditions for instilling a lifelong fondness for fragging. Evan also leads production of the PC Gaming Show, the annual E3 showcase event dedicated to PC gaming.