Our Verdict

A no-fat riff on the early days of survival horror that knows just what to streamline and what to keep pleasingly obtuse.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? Survival horror from the days when CRTs made everything scarier (and fuzzier)

Expect to pay: $20 / £17

Developer: SFB Games

Publisher: SFB Games

Reviewed on: Intel i5-13600K, RTX 3070, 32GB DDR4

Multiplayer? No

Steam Deck: Verified

Link: Official site

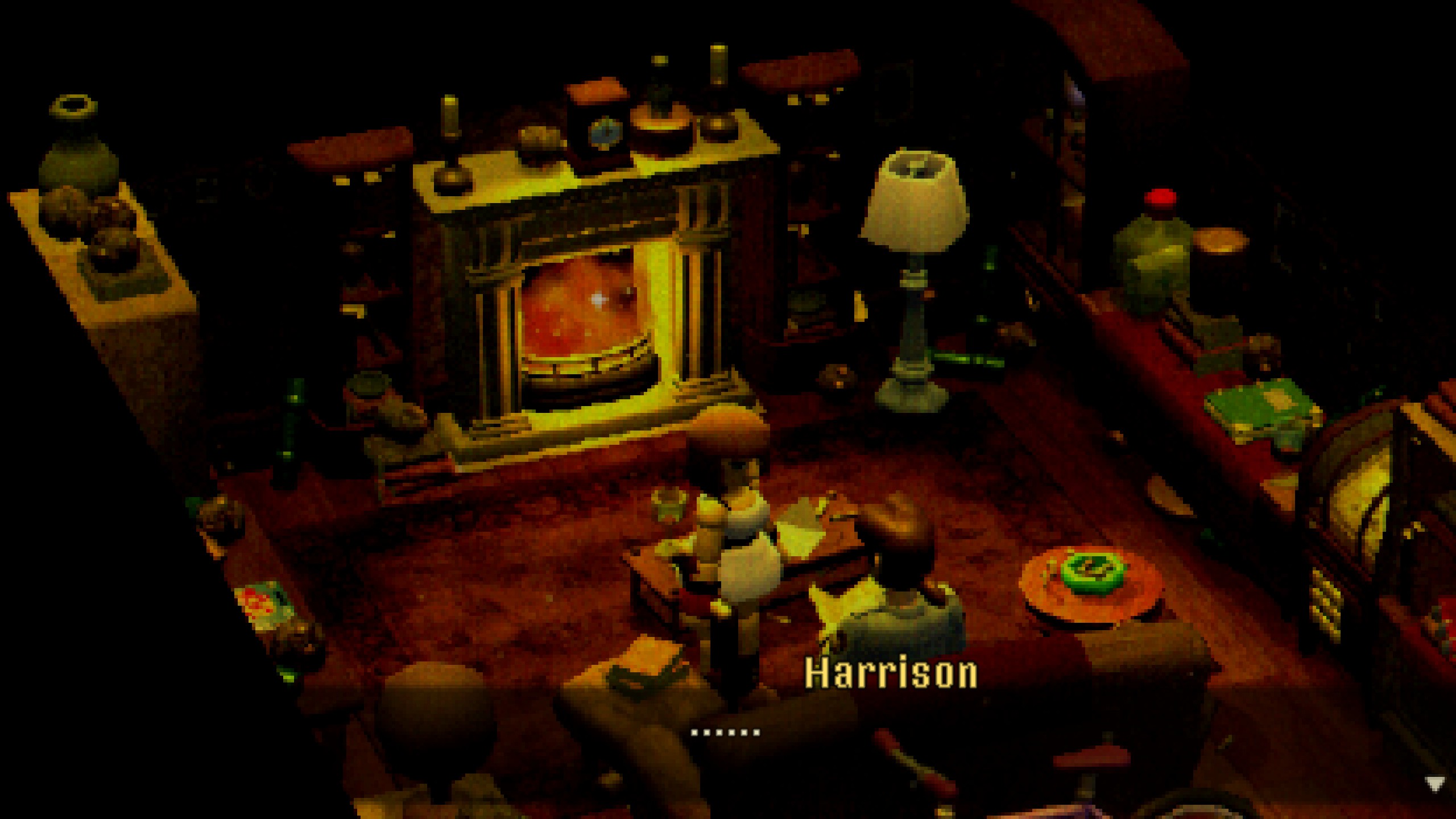

Crow Country is a VHS home movie of a kid's amusement park recorded in 1997, then left in a hot, fetid cabinet until the tape has warped and mildewed. A yellow visual smear gives its throwback graphics a rich but fuzzy CRT texture, muddying everything enough to add a patina of creepiness impossible under the harsh light of high definition. If horror movies have taught me anything, it's that when you find an object at the back of the cupboard that has every chance of being cursed you can't, like, not watch it.

You gotta jam that thing into a VCR, then obstinately shrug off the ominous vibes that begin to cloud your waking life. Was Crow Country sneakily manifesting new items into rooms I'd already wandered through just to mess with me, or had I simply missed that welcome medpack nestled on a grimy shelf through the haze? Am I just imagining things?

Nah—tape's definitely haunted.

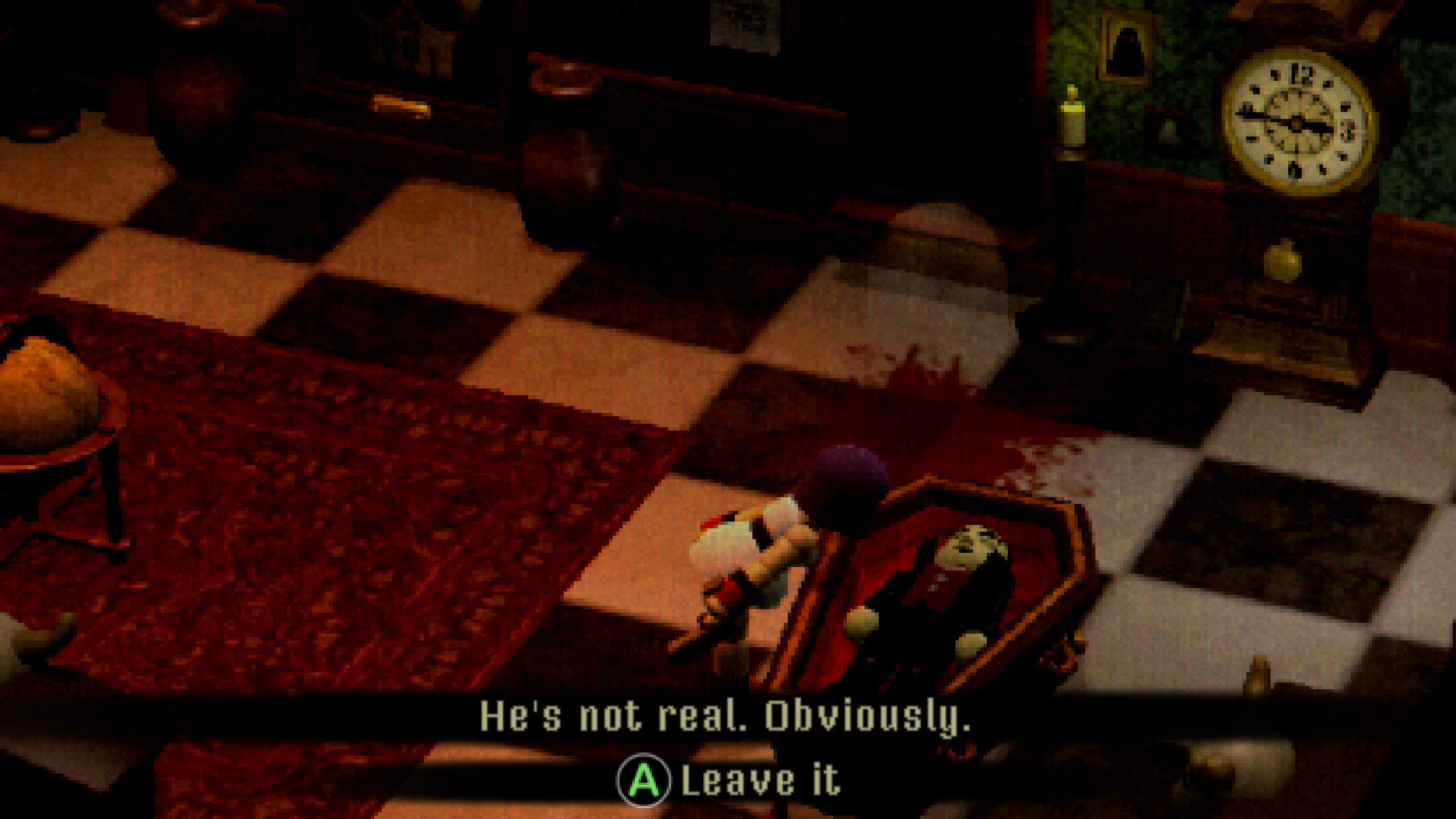

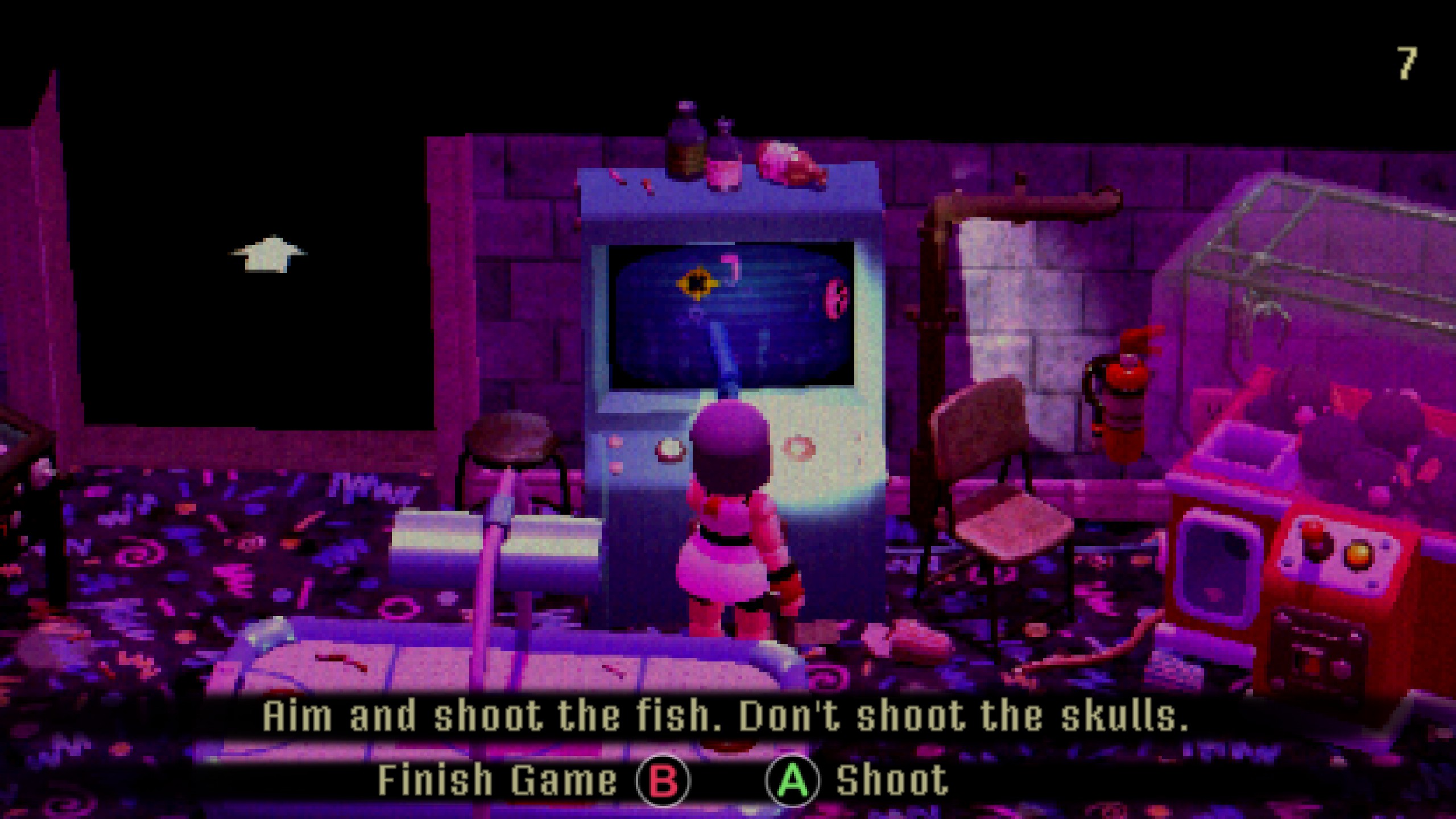

This snack-sized bite of PlayStation-era survival horror makes a strong case for horror games that can comfortably fit within the length of a VHS tape. I beat it in five hours across two sittings, the perfect amount of time to spend unspooling a series of Resident Evil mansion-style puzzles as I worked my way through the rotting remnants of Crow Country's gift shop and haunted house and undersea arcade.

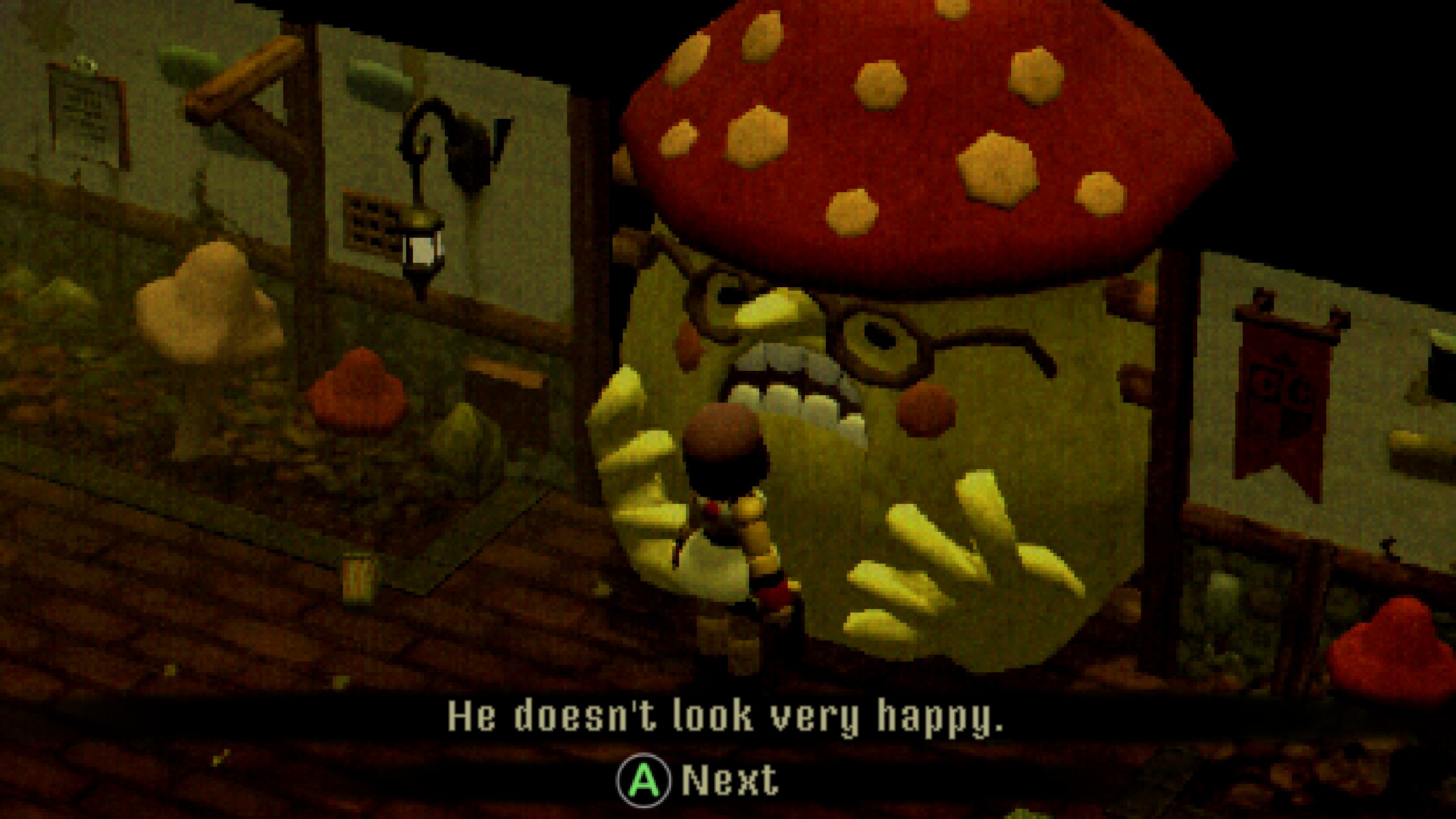

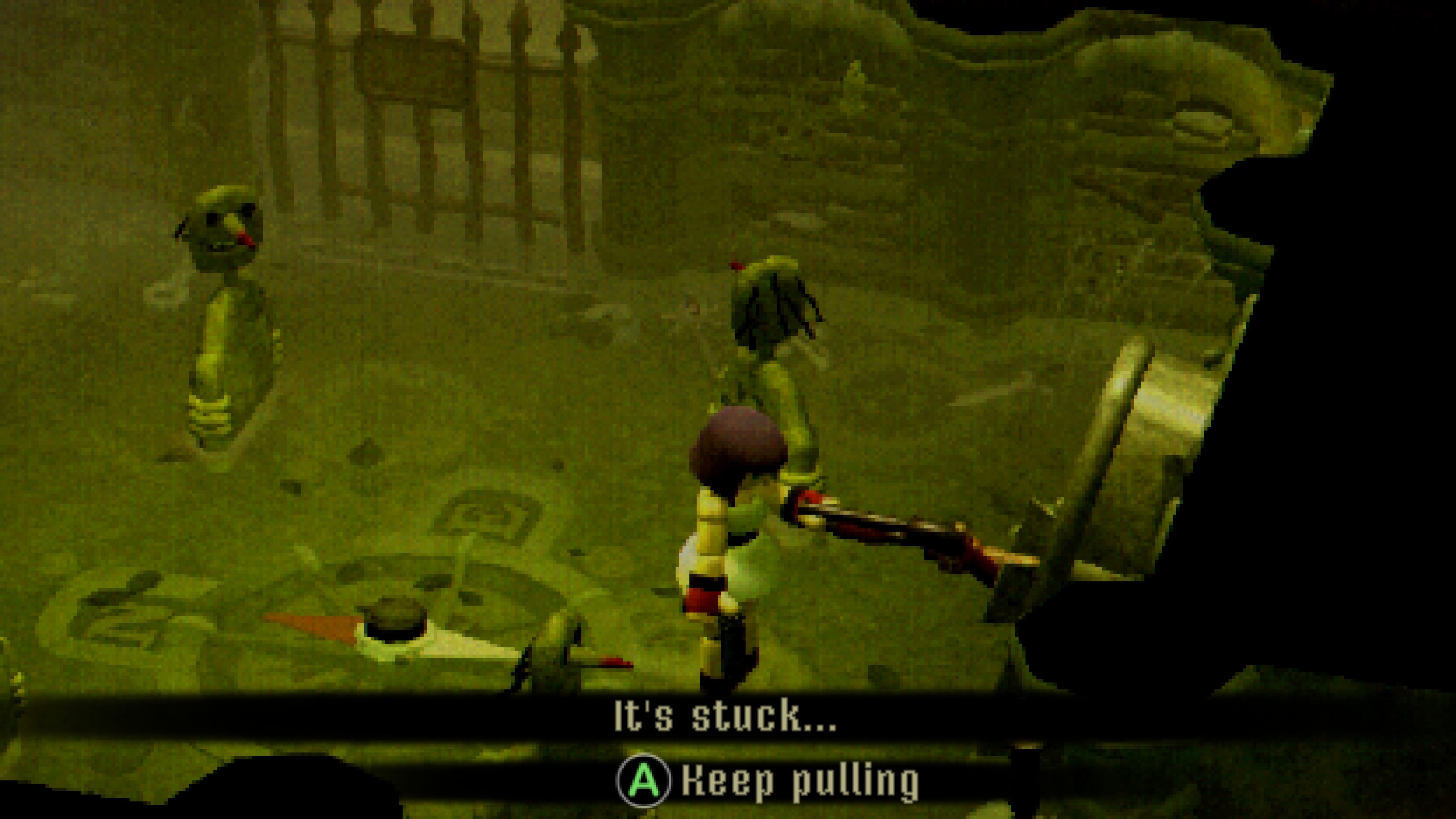

In those five hours I played notes on a piano to open secret compartments, solved a gravestone riddle while a hand jutting out of a clock menaced me with a shotgun, and jolted back in my chair at least twice when Crow Country nailed me with jump scares. This is not the kind of horror that soaks you in constant, high fidelity dread, but it does have the kinds of demented monster designs that immediately make the skin crawl when you see them in the distance.

Imagine a circus performer on stilts, only bowed over on all fours and stripped down to bone. As with Dark Souls' skeleton beast, spotting one of these out of the corner of your eye elicits an immediate and primal "nope." I regret to inform you there is a blood-soaked baby that looks like Pinocchio fresh from the womb. I yelled at it when it skittered across the floor at me just when I'd come to expect most of Crow Country's monsters to be slow shamblers.

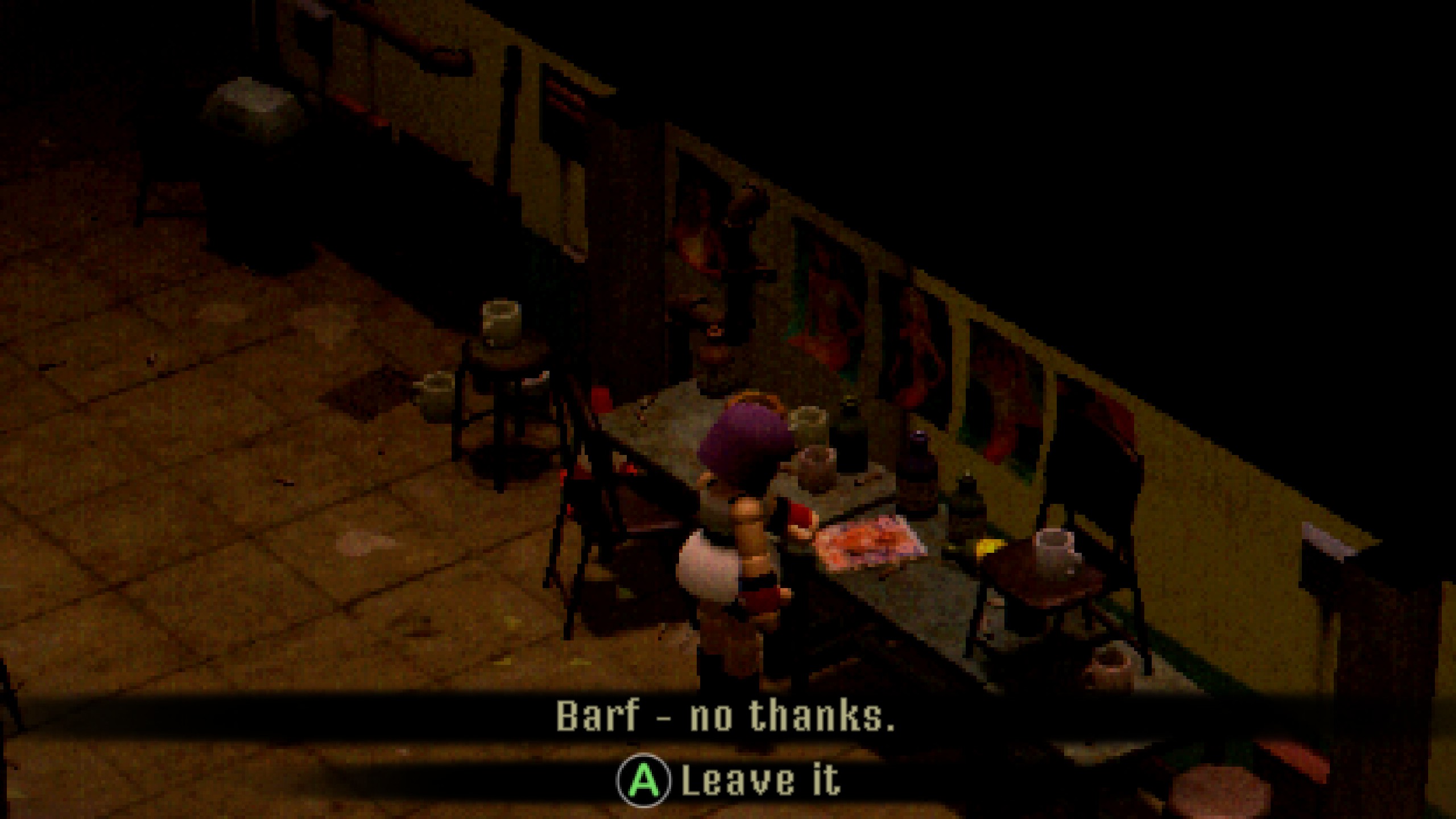

Crow Country is funny as often as it is scary, thanks to some wry writing—my character reacting "Barf, no thanks" while investigating an adult magazine or "It's a computer" while looking at a computer. (The game's set in 1990, when "It's a computer" was still a more novel observation). There are also plenty of cheeky nods to game and horror tropes; of course the combinations of items you need to use to solve any given puzzle are absurd, the guy running this theme park has lost his damn mind!

There's no shortage of games today cleverly reaching back into the past to pluck ideas and aesthetics that still work today, but Crow Country feels like a true case study for retro-modern survival horror. With a gamepad I could freely move around in 3D with one analog stick and rotate the camera with the other, or I could move my thumb over to the D-pad and play with the tank controls that Resident Evil has long abandoned. Aiming and shooting with the isometric camera is deliberately awkward, adding a fumbling tension when monsters shamble toward me.

There are little niceties I deeply appreciated, like a catalog of all the notes I'd collected around the park bundled up at each save point, so I could flip through the remaining clues.

All the characters look like Playmobil figures with extra baby fat around the joints, and as an aging millennial a fire lights up deep within me whenever I see videogame graphics that remind me of Cloud Strife's old Popeye arms.

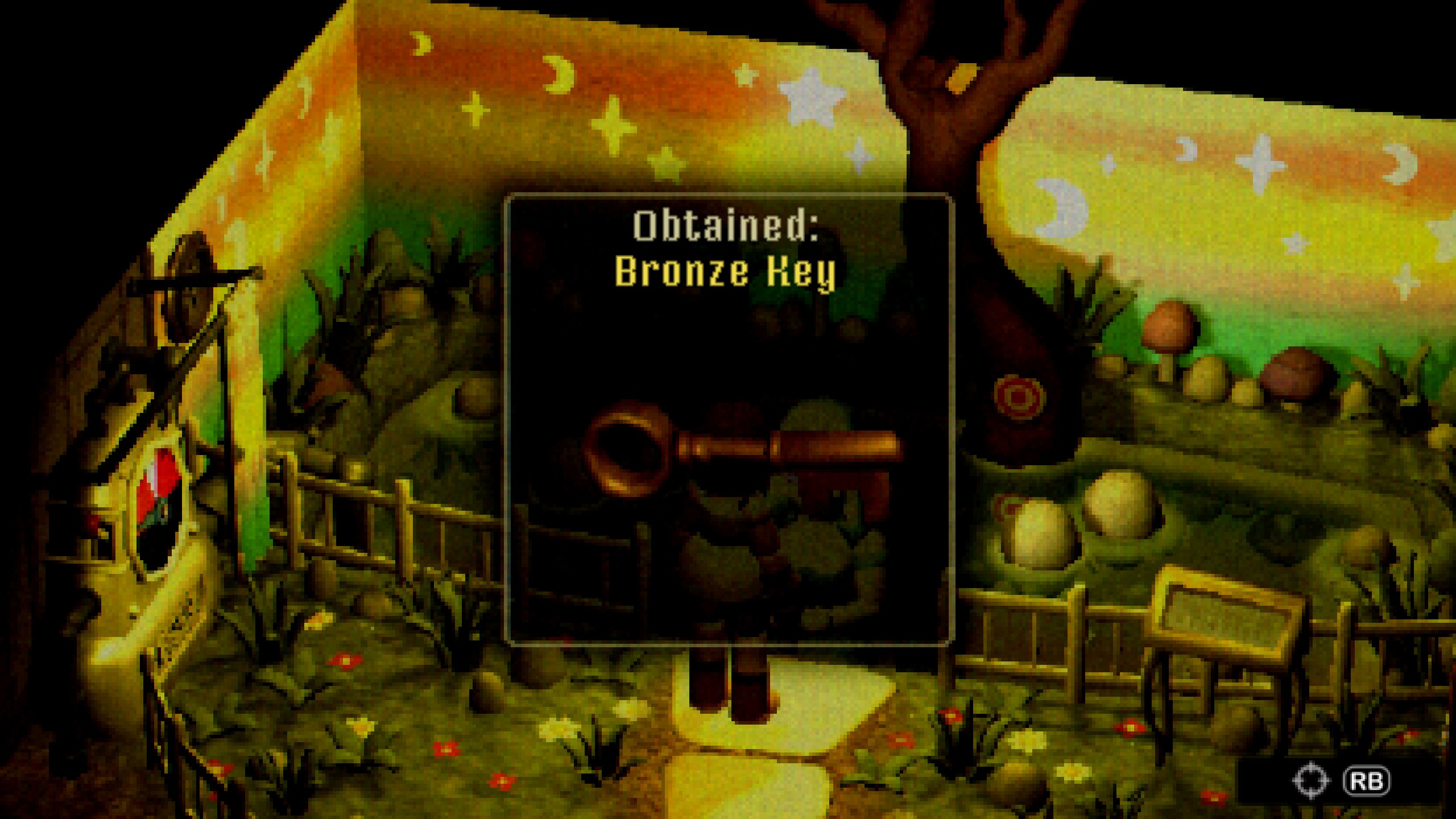

Crow Country makes the safe bet that there are a lot of people like me who'd rather play a five hour horror game than a 15 hour one, that will feel satiated with a few good jump scares, satisfied after a dozen-or-so puzzles and nod in appreciation at the way the park gets more and more haunted as the game progresses, even if it never ends up particularly challenging. A few puzzles bordered on too obtuse, where I knew what I needed to do but struggled with how the game wanted me to do it, and I would've appreciated some map icons showing me where the hell to backtrack when I finally got my hands on the bronze/silver/gold keys. But there is a generous hint system for getting over these humps, which I didn't mind using when I was unsure if I actually had what I needed to progress.

I never died or even ran low on healing items, and the enemies are generally creepier than they are threatening. It's probably tuned to be too easy, but that just contributed to the feeling that Crow Country and I were on the same wavelength—we were both there for a good time, not a long time. Priority #1 was ensuring our time together never dragged.

None of the puzzles gave me a particularly memorable aha! and the combat never stretched beyond comforting simplicity, but I'd happily play a couple Crow Country-sized horror games a year just to see which bits of '90s game design they lovingly rejigger. It took me playing most of Crow Country to put my finger on it, but finally I realized exactly what pop culture memory it had brought bubbling up from the depths of my mind: that moment in Toy Story when Buzz and Woody first meet evil neighbor Sid's twisted menagerie of toys, like the one-eyed baby doll head bolted to the erector set spider legs. Freaky on the surface? Absolutely. But once the shock wears off, they couldn't be a warmer, friendlier bunch.

A no-fat riff on the early days of survival horror that knows just what to streamline and what to keep pleasingly obtuse.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).