Big studios can't hide crunch anymore, so they just admit to it

The game industry's long hours used to be an open secret, but two major developers have a new tactic: transparency.

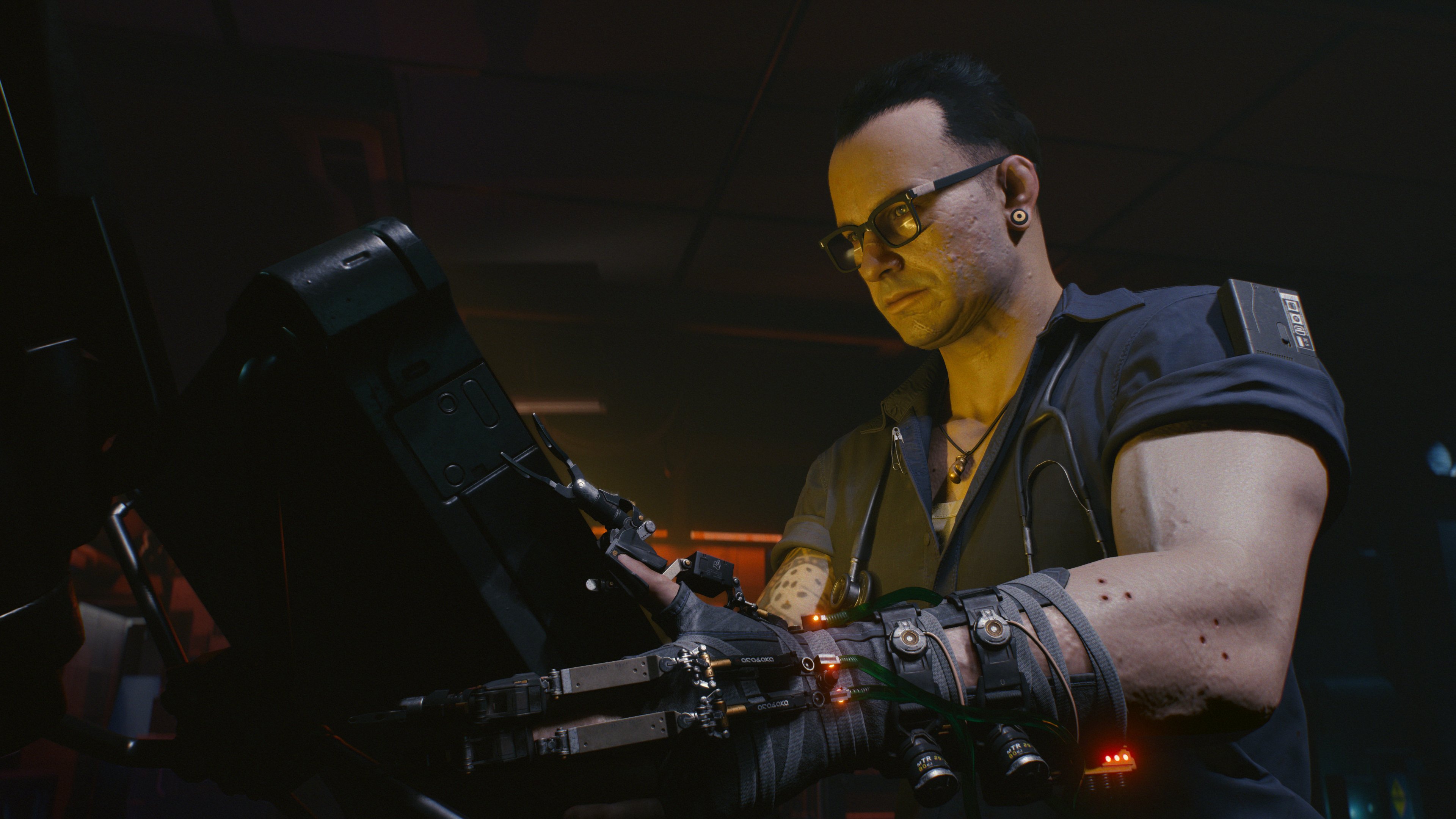

CD Projekt Red is going to crunch. That information did not come from tradeshow rumblings, or scattered Twitter innuendo, or a 6,000 word exposé. Instead, it came from Adam Kiciński, co-CEO of the company, who said as much during a conference call shortly after the announcement of Cyberpunk 2077's delay.

"[We] try to limit crunch as much as possible, but it is the final stage. We try to be reasonable in this regard," he said. "But yes, unfortunately [the team will be required to crunch]."

To some, Kiciński's comments came as a disappointment. In 2019, CD Projekt Red went on record saying they were hoping to create a "more humane," "non-obligatory" crunch environment for Cyberpunk, one that wouldn't result in the long hours and resentful former employees that The Witcher 3 left in its wake. His most recent statements aren't supremely reassuring, and surprisingly, this was the second time in January a high-ranking developer acknowledged that their team was toiling under a crunch schedule. The other was Marty Stratton, executive producer of the forthcoming Doom Eternal, who told VG247 that the game's push into 2020 required id Software employees to crunch "pretty hard."

"It goes in phases," he continued. "We’ll have one group of people crunching so the next group of people are teed up properly. As they get done, they may need to crunch a little bit. We really truly do try and be very respectful of peoples’ time and lives. We have very dedicated people that just choose to work a lot in many cases. It was nice because we want the game to be perfect. We want it to live up to our expectations and consumer expectations."

For years, crunch has been the game industry's open secret. You don't need to look far to find horror stories of programmers logging 100-hour weeks to hit street dates, and some companies, such as Rockstar, have grown infamous for the labor burdens that flare up during their decade-long development cycles. These systemic issues are ancient, but there are efforts to fix them. Groups like Games Workers Unite are attempting to create some sort of union canopy to protect game development workers, and more workers are coming out in favor of unionization in general in response to mass layoffs and patterns of crunch.

Even US politicians like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and have expressed their support of game developers.

Shout out to the tech and game industry workers organizing w/ @CODE_CWA and @GameWorkers for taking a stand with #TechAgainstICE, fighting for gender equity, and improving working conditions in gaming + tech! 🎮👩🏾💻👨🏼💻👾 https://t.co/b18ecJMbTIJanuary 16, 2020

The video game industry made $43 billion in revenue last year. The workers responsible for that profit deserve to collectively bargain as part of a union. I'm glad to see unions like @IATSE and the broader @GameWorkers movement organizing such workers. https://t.co/Ia5gMG2v0wJune 18, 2019

That pressure has forced studios to speak candidly about their efforts to hammer their workweeks into something more equitable. In that sense, these disclosures from CD Projekt Red and id Software can be read as either a repudiation or an acknowledgement of that momentum. But we shouldn't confuse transparency with good labor practices.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It's certainly novel that executives are willing to speak publicly about the long hours their development goals and deadlines have required. In the past, crunch was typically not talked about, forcing reporters to evaluate the carnage from anonymous employees who log aggrieved Glassdoor assessments of company culture long after the damage has been done. If you're charitable, you could say that Kiciński and Stratton's contriteness allows consumers to make a more educated, sympathetic decision when Doom Eternal and Cyberpunk 2077 release. If you are passionate about labor equity for developers, it is nice to know exactly what kind of personal burnout was poured into the glistening skyscrapers of Night City. At the very least, we know what CD Projekt Red management decided was an acceptable cost. But as much as it might be unpopular in media and message board circles, that sort of discretion won't affect preorders.

I spoke to a former Rockstar employee who compared working at the company to "joining the cult."

It's discouraging to know that despite how martial the crunch discourse has become, managers are still justifying it with the same excuses. Stratton used a classic: "We have very dedicated people that just choose to work in a lot of cases." Developers are passionate about their games, but that does not account for the social pressure and hierarchical incentives that feed crunch culture. If a boss opens the door to a 100-hour workweek, there is no scenario where a worker can consider that work completely optional. I spoke to a former Rockstar employee who compared working at the company to "joining the cult"—that the company considers it an honor to sacrifice your body for the product. For as much as management might apologize about crunch, it still feels like the norm.

"This approach to making games is not for everyone. It often requires a conscious effort to 'reinvent the wheel'—even if you personally think it already works like a charm," said CD Projekt Red co-founder Marcin Iwiński and studio head Adam Badowski, when they first defended the company's crunch policies back in 2017. "But you know what? We believe reinventing the wheel every friggin' time is what makes a better game. It's what creates innovation and makes it possible for us to say we've worked really hard on something, and we think it's worth your hard-earned cash."

Making video games is hard, and nobody would argue that it's impossible to feel the blood, sweat, and tears zealotry that Badowski, Iwiński, and Stratton describe. But crunch relies on sustaining the myth that passion and creative satisfaction require casting aside concerns about mental health and physical exhaustion—that a reasonable relationship with work is undesirable and even impossible when you're making games at a big studio. That justification isn't getting any more convincing.

Luke Winkie is a freelance journalist and contributor to many publications, including PC Gamer, The New York Times, Gawker, Slate, and Mel Magazine. In between bouts of writing about Hearthstone, World of Warcraft and Twitch culture here on PC Gamer, Luke also publishes the newsletter On Posting. As a self-described "chronic poster," Luke has "spent hours deep-scrolling through surreptitious Likes tabs to uncover the root of intra-publication beef and broken down quote-tweet animosity like it’s Super Bowl tape." When he graduated from journalism school, he had no idea how bad it was going to get.