Back in 2006, this tiny indie developer made a mecha game that reveres Sega's Virtual On as much as I do

Iron Duel is as obscure as Japanese doujin games get, but it shows what happens when a fan team dreamed big.

Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialist '80s computers to the happy days of Windows XP.

In 1997 Sega's nigh-undefeatable arcade division created Virtual On, an arena-based fighting game starring giant mechs able to rocket boost over buildings and unleash screen-sized lasers at each other. As with everything the company released in arcades back then the game was built upon an eye-catching "more is more" philosophy, using cutting edge technology to deliver graphics that at the time were truly impossible to replicate at home. This already overwhelming sensory experience was then housed in a cabinet featuring an unusual twin stick control panel and large cockpit-like seats for maximum effect. Virtual On was a success and became the first entry in a small series that is still beloved today, in spite of the lengths and expense people often have to go to to play them.

Doujin game developer Blue&White gazed upon this glorious fusion of neon and metal running on specialist hardware and said "Yeah, we can do that too," even though it had only released a couple of shmups and dabbled in basic 3D modelling at the time. Some types of games suit doujin-sized development teams like a glove—there's a practical reason why there are so many indie roguelikes and retro-style arcade games. Speedy mech-on-mech 3D action definitely isn't one of them.

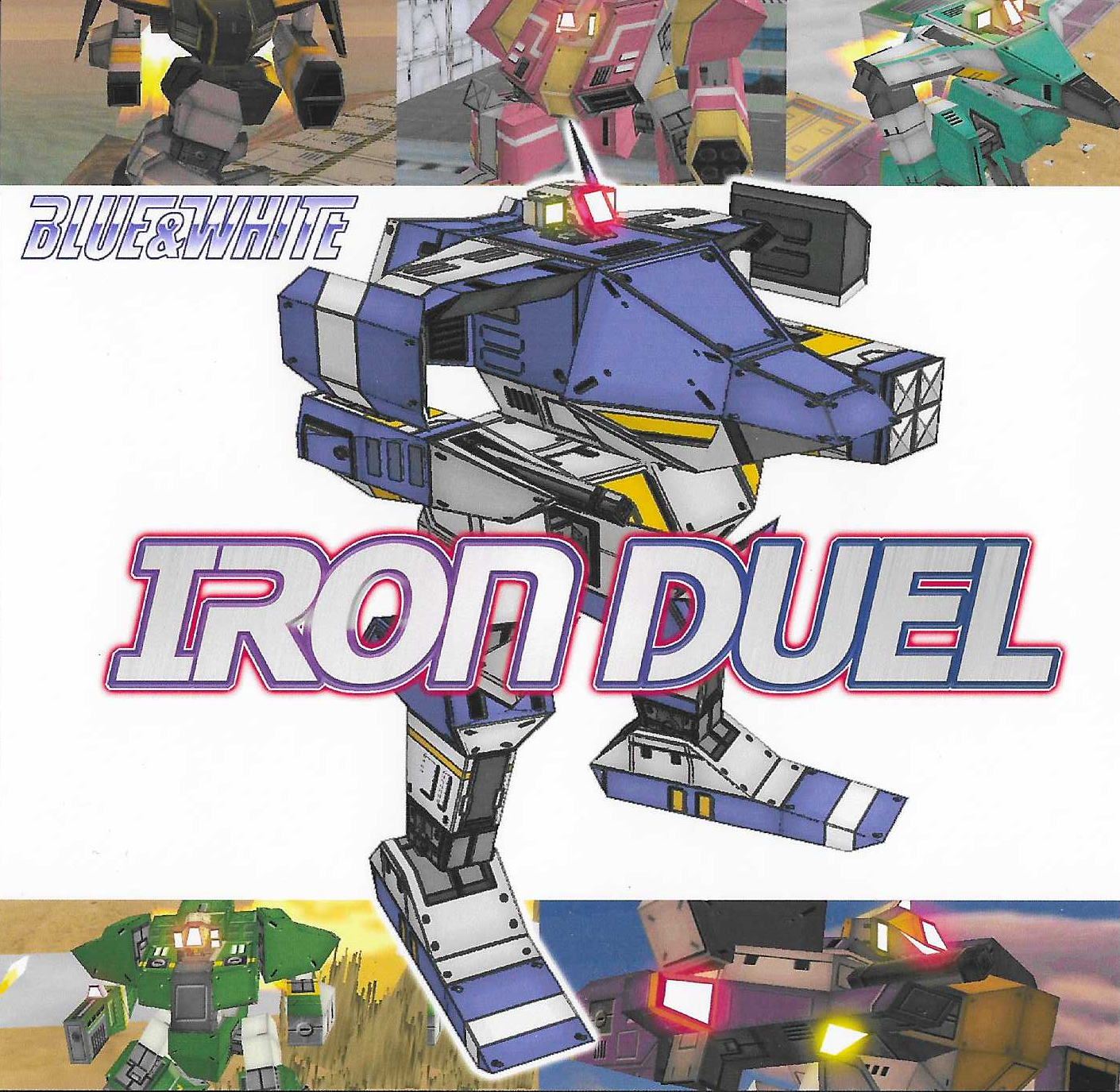

Yet the indie team at Blue&White actually followed through on their wildly ambitious idea and released Iron Duel on PC sometime around 2006. Its clash of metal and missiles was contained within a simple burned CD-R with printed inserts so basic the back "cover" of the game's slim CD case is nothing more than a loose sheet of paper with a link to the developer's old Geocities website printed at the bottom.

2006. An ancient time where mainstream PC games still routinely came in boxes, Windows Vista hadn't been released yet, and The Elder Scrolls 4: Oblivion was forcing everyone to have an opinion on horse armour. We were still years and years away from Recettear's Steam debut, a quietly revolutionary event that would slowly but surely raise English language awareness of doujin games and eventually turn them into a viable (and buyable) niche on our side of the internet. Yet this was the era Iron Duel was created in, and looking at it in this broader context it's clear just how much of a pioneer it was, charging ahead in a genre doujin games never played in.

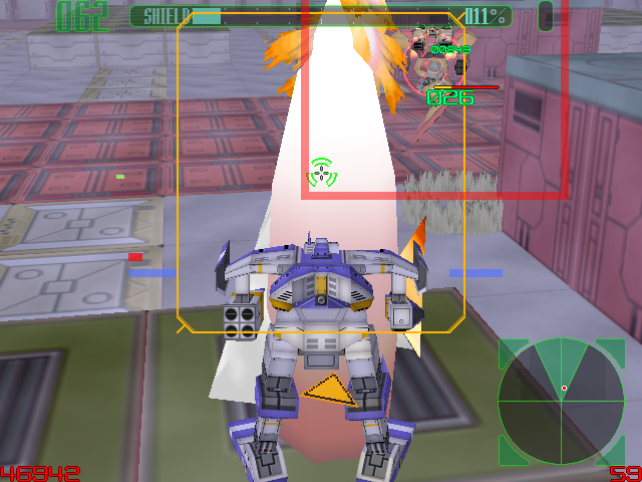

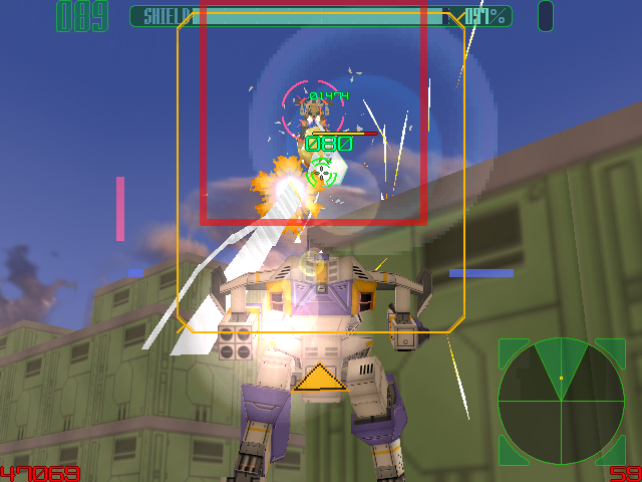

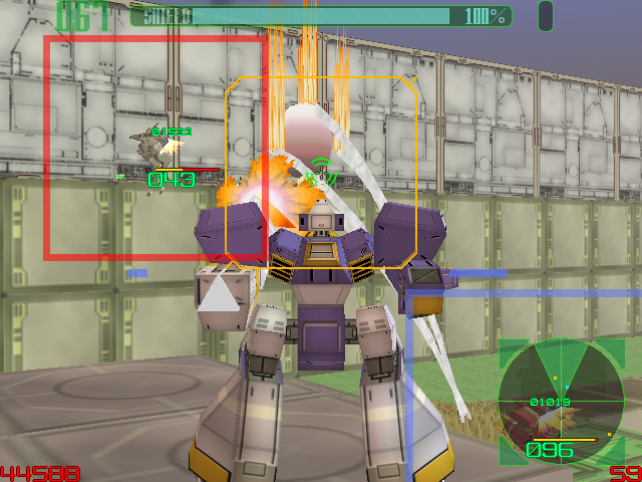

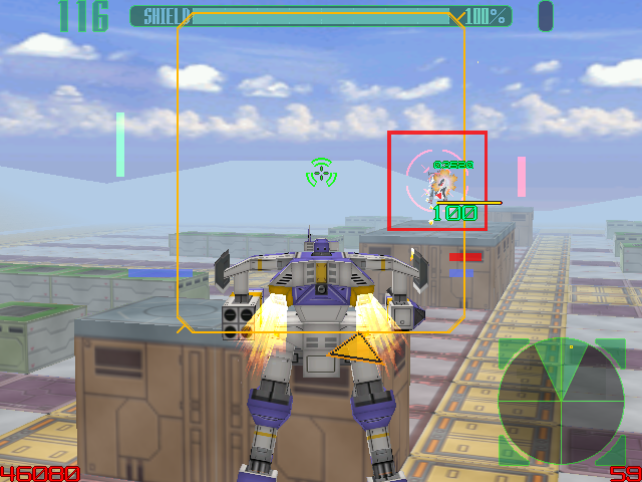

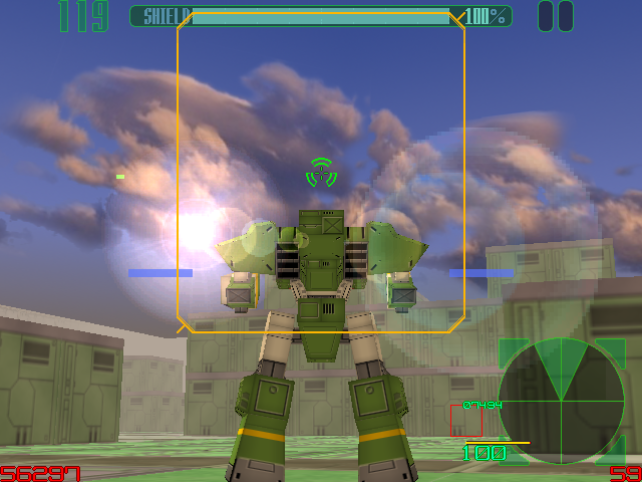

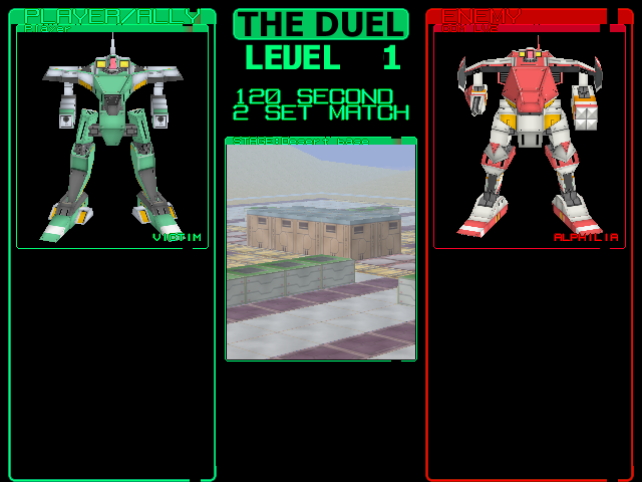

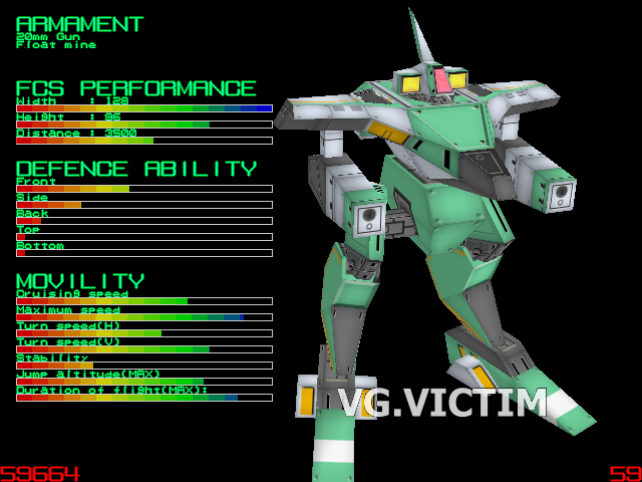

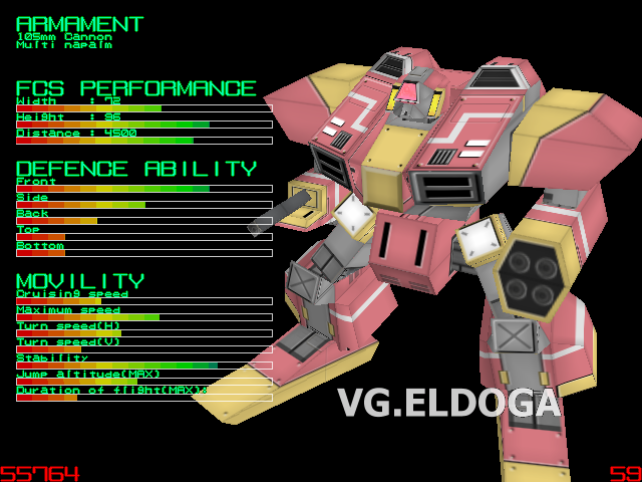

In spite of its status as a bold and experimental step into relatively new and uncharted territory, the game still features six playable mechs ranging from versatile all-rounders to lumbering specialists, each with unique weapon loadouts designed to generate as many brilliantly blocky 3D explosions and lasers as possible. Iron Duel's simplistic look, all sharp angles and simple, crisp, textures, accidentally evokes a nostalgically retro style of 3D long before that trend would eventually take off, and luckily for Blue&White it suits mech action especially well. Giant bomb-throwing machines should have large, flat, surfaces and boxy shapes on the end of squarish arms. Their hips should rotate independently of the upper body. Jet booster effects should be made from raw spiky polygons and missile trails should always be triangular.

These Virtuaroids—sorry, Vertical Gunners—blow each other to bits in a variety of arenas and under various circumstances, even if some of these rules don't fit the original Virtual On setting Iron Duel is trying so very hard to imitate. The duel battles in here are cribbed from the much later Virtual On Force (internal consistency isn't exactly something a fan-made work born out of pure passion has to worry about).

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Fan games don't really have to worry all that much about being any good, either. Iron Duel exists because it can, because someone out there wanted it to, and that highly personal passion's a good enough reason all by itself. Is it some sort of long-hidden gem, or a particularly novel twist on an established formula? No, it's not either of those things. It lacks Virtual On's showy charisma. The controls used to guide your Vertical Gunner to victory never quite feel right no matter how much you tweak them. The ally AI as well as general hit detection remain somewhat questionable even after the game's been patched up to its virtual eyeballs.

And in this instance, that's OK. I didn't install this hoping to see Sega beaten at their own game, and really, it wouldn't have been fair of me to expect this indie upstart to outdo its inspiration's stunning Hajime Katoki (Gundam, Patlabor, Super Robot Wars) Virtuaroid designs anyway. I installed this because as a Virtual On fan I had a rare and precious chance to play something new for an afternoon. It's a bit like hearing your favourite song sampled by some new artist you've never heard of on the radio—it doesn't really matter if I like the way it's been reimagined or prefer the original, because either way it still feels like a happy meeting of like-minded fans.

Iron Duel's handcrafted CD is a love letter to a series the developers clearly care for at least as much as I do. It's a big idea burned onto a small disc, and even though their game didn't turn out to be amazing I'm still glad they got to share their obvious passion for Virtual On with the world—and with me.

When baby Kerry was brought home from the hospital her hand was placed on the space bar of the family Atari 400, a small act of parental nerdery that has snowballed into a lifelong passion for gaming and the sort of freelance job her school careers advisor told her she couldn't do. She's now PC Gamer's word game expert, taking on the daily Wordle puzzle to give readers a hint each and every day. Her Wordle streak is truly mighty.

Somehow Kerry managed to get away with writing regular features on old Japanese PC games, telling today's PC gamers about some of the most fascinating and influential games of the '80s and '90s.