Where the Goats Are is like Stardew Valley but all you have are goats, chickens, and crushing loneliness

And yet, the act of play is surprisingly important.

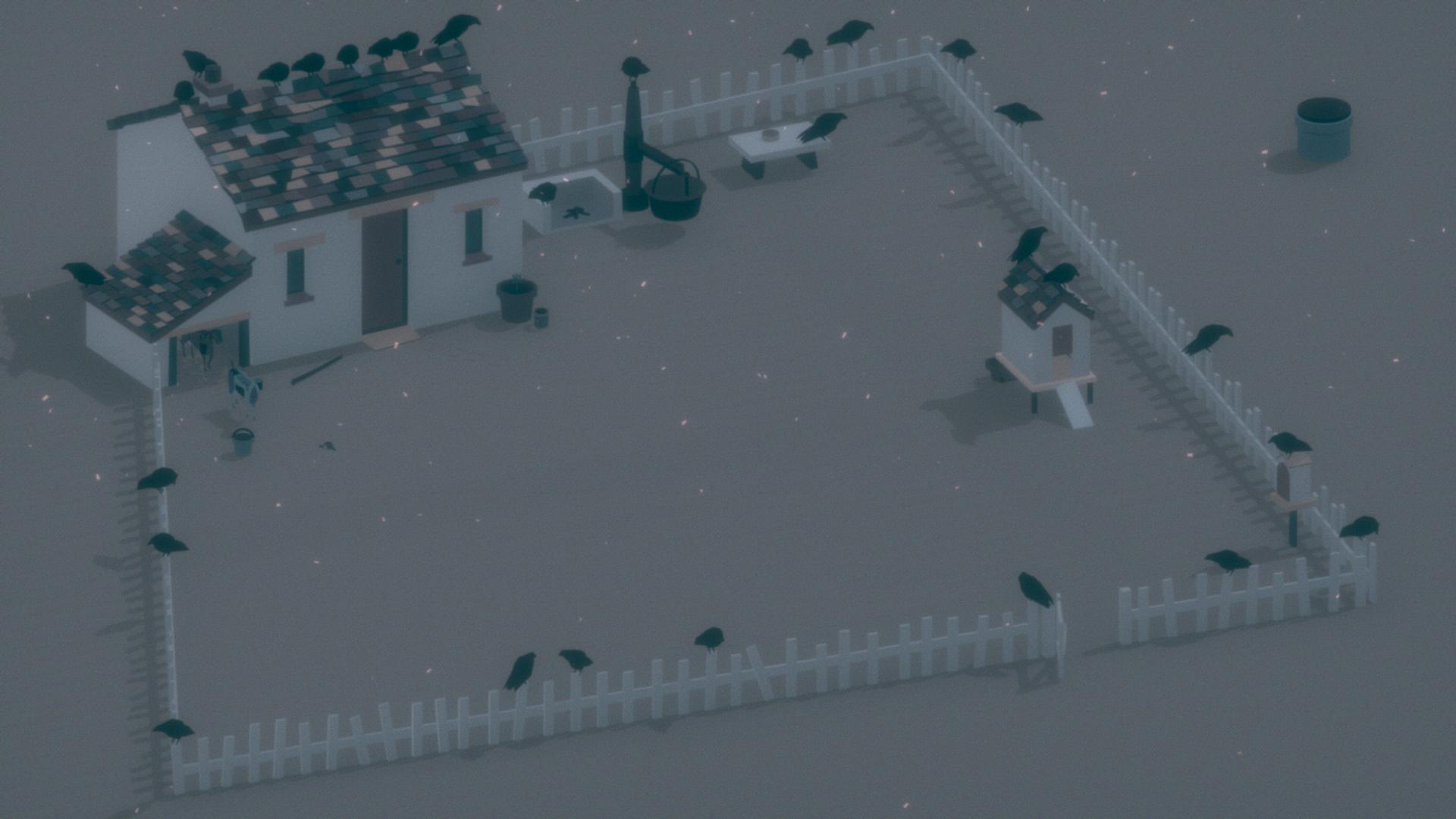

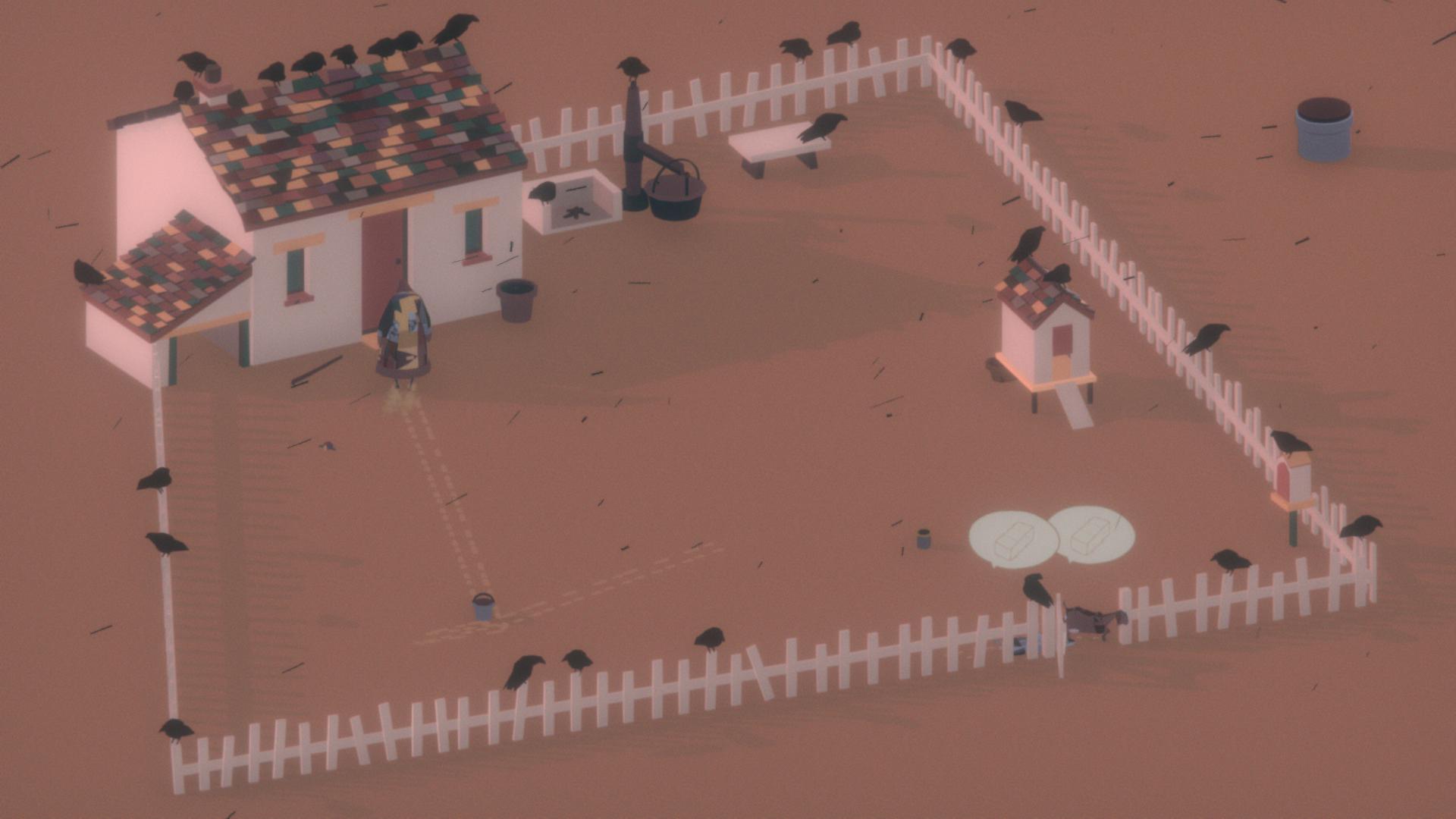

Where the Goats Are is a narrative game about a rural homestead at the end of its long, peaceful, self-sustained life. The player controls its ageing owner and sole resident, Tikvah, who spends her days making cheese, collecting chicken eggs, and, of course, taking care of her goats. If she has a spare moment, she might water her plant, draw pictures in the sand, or pray.

There's no shortage of serene narrative "experiences" in the indie game scene. From the popular magical realism of Kentucky Route Zero to excellent grandma tribute Lieve Oma to experimental pseudo-multiplayer dying-on-an-alien-planet simulator Orchids to Dusk, players are spoiled for choice when it comes to chilled-out dawdlers structured around a particular story or interpretation.

With its minimalist art style, sparse sound design, and Deep Philosophy that Totally Makes You Think (Dude), it might not appear that this goat-centered narrative game by Memory of God is going to offer more than what's par for the course in this already well-populated sub-subgenre. Happily, after a number of playthroughs with Tikvah and her goats, I've found this isn’t the case at all. It's a literal and figurative sandbox that ensures it isn't strictly bound by a single message in the way its contemporaries can be. Out here, where the goats are, we decide what’s important.

(Note that this article will spoil parts of Where the Goats are for you. If you haven't played it, it's available on itch.io and you can name your own price.)

How to locate goats

That said, I can't help but look back on my initial playthrough with the feeling I did something wrong. What I found on that first blind go-around, tucked away behind goats, chickens, and a slow-burning tale about the end of the world, was—well, a game. More specifically, a simple point-and-click management game about cheese production, goat acquisition, and septuagenarian piloting. A game about achieving as much as possible before Tikvah's time is up, and ignoring absolutely everything else—especially whatever this tiny homestead has to say about globalization, death, and goats.

Though Where the Goats Are is technically a micro-sandbox, Memory of God's storefront description of this game as a "slow-paced, meditative" experience suggests a cold, calculated, achievement-focused playthrough might be the wrong way to play. But in a game open to choice and interpretation, is there such a thing as an "incorrect" approach?

In my sheer ignorance of the game's narrative underpinnings and my heartless quest for a high score, was I doing what I was supposed to be doing, or am I just an idiot? Let's find out together.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Life on Sim Homestead

The events of Where the Goats Are take place during a period of rapid downturn, as an unseen apocalypse in the outside world slowly and steadily impacts Tikvah's homestead. Our only knowledge of what's really going on comes in the form of daily letters from Tikvah's family and friends, which begin as warm correspondence and end as desperate outpourings scrawled onto napkins.

Importantly, the player is left to figure out the major point-and-click mechanics (cheese-making, chicken-rearing, plant-watering, etc.) themselves. This is fine because, narratively speaking, there's no pressing need for that figuring out to happen. Even Memory of God suggests that arguably "everything is optional".

Whether or not we make cheese, collect eggs, read letters, or do anything at all, the outcome remains the same. Tikvah, her goats, and her homestead will all die. And therein lies what the game is really about: deciding how Tikvah will spend her last days.

My first experience with Where the Goats Are came before knowing any of this. When I loaded the game I knew only three things about it: it had a pleasant art style, the player-character was an old lady, and goats always rock. As such, being the obsessive and achievement-driven player that I am, I figured that this was a game about making cheese and buying goats—a minimalist take on mobile game Hay Day, if you will.

Although it's clear in hindsight that there's far more to Where the Goats Are than this, I interpreted a number of the mechanics as signs that there really was a core game to be played.

Firstly, there's the cheese wheels. These large, golden, coin-looking pieces of currency can be traded for goats and goat feed from the traveling merchant who visits each evening. By focusing on cheese production and purchasing just enough goat feed to get by, I found that the surplus of wheels was enough to bring more goats into my fledgling machine of cheese-scented capitalism.

More goats mean more cheese, which mean a wealthier Tikvah. The small pot plant outside the cottage represented a similar measure of success. If I helped it grow by watering it daily, what would I be rewarded with?

There's also the game's precise pacing. The days are too short and Tikvah is too slow for me to complete every daily task—a mechanic I interpreted as part of the challenge. In my attempt at a winning playthrough, I found there was just enough time to milk the goats, make the cheese, catch the merchant on his way past, water the plant, and collect eggs from the chicken coop before darkness fell.

There was absolutely no time to waste praying, petting the goats, or opening the mail, the encyclopedic content of which would have me reading—and thus wasting precious labor time—long into the evening. I thought I was a min-maxing genius.

Soon, I found myself theorycrafting the most efficient Tikvah routes. While the milk was being fired in the morning, I would quickly grab the egg basket and water bucket and place them on the routes to the chicken coop and water well respectively. Doing so shaved precious seconds off my average lap time.

By the end, Tikvah was no longer Tikvah—she was a granny-shaped, soulless agent of capitalism whose only purpose was to satisfy my quest for peak cheese gains, efficient goat maintenance, and whatever the prize was for growing the biggest plant. She existed to answer the question, what would I be rewarded with in return for my dedication and mad skills?

The greatest consolation prize

The answer, of course, is nothing. Like I said earlier, all we do in Where the Goats Are is decide how Tikvah spends her last days. In retrospect, my focus on homestead microeconomics might be considered an insult by the old lady who really doesn’t need her quiet life usurped by the brutality of hard graft.

But I'm not here to ask if my original, naive approach was OK with Tikvah (I assume it wasn't). Instead, I'm here to ask if it holds any value at all, at least in terms of how one might measure any given Where the Goats Are playthrough.

The answer I'll present is a tentative "sorta".

My first playthrough was born out of equal helpings naive expectation and misinterpretation, and as counter-intuitive as this run must appear in a game concerned with ideas far grander than "make cheese, get bitches more cheese," I nonetheless believe that the narrative includes something of a consolation for achievement-focused folks like me.

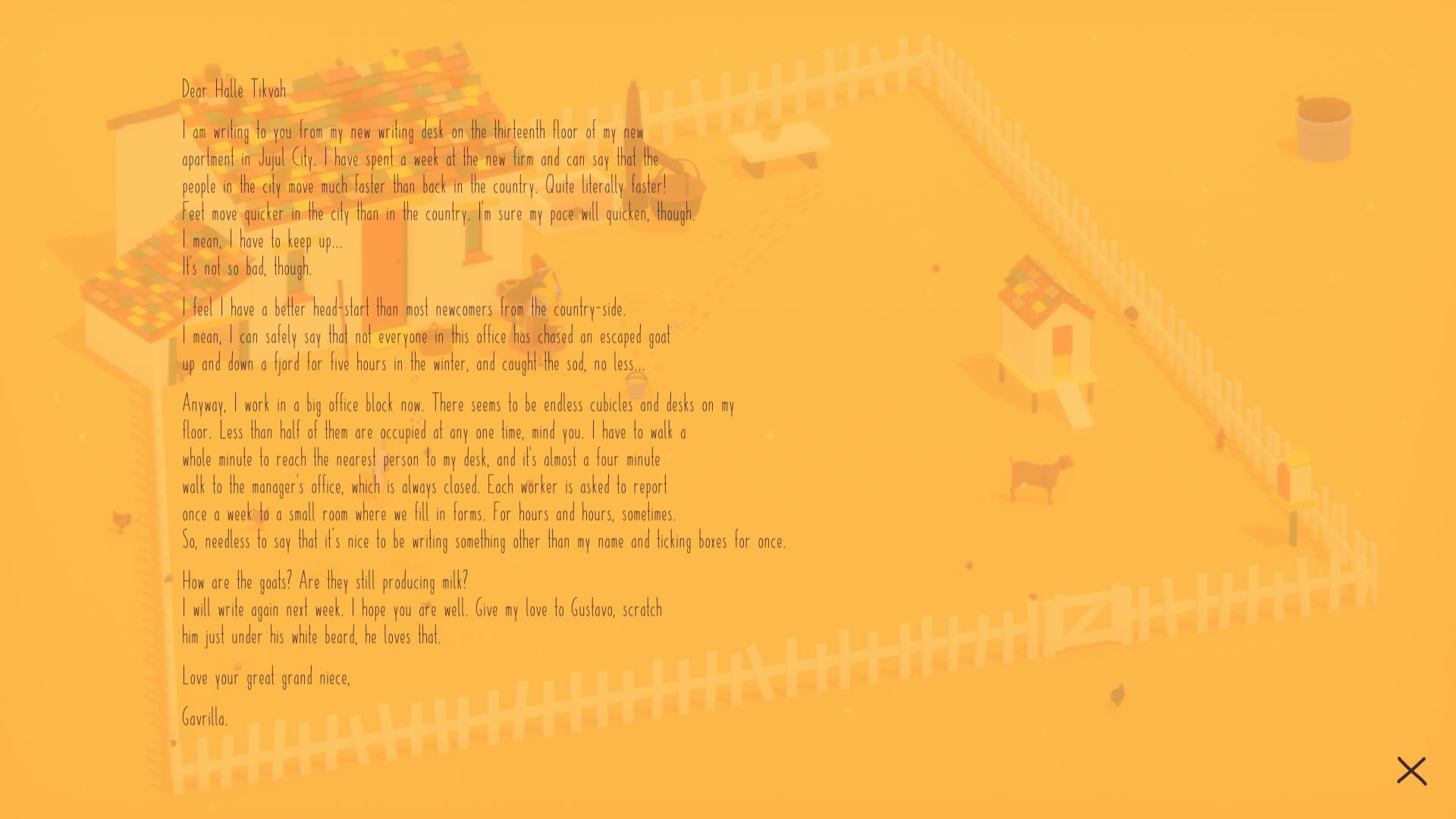

Early on, Tikvah receives a letter from her great-grandniece Gavrilla. In the letter, Gavrilla reminisces about childhood experiences with Tikvah while speaking with uncertainty about her new, crushing office job. Although it's clear that Gavrilla's true place is with Tikvah and the goats, she can't bring herself to see past her own ideas about what she's supposed to be doing in her professional life. She even states that she "has to" keep up with the pressures of her new job, but doesn't provide a reason for why that is.

I can't help but see myself in Gavrilla. Though there's nothing explicitly wrong with the way our naivete caused both of us to default to a superficial approach to life and/or virtual goat care, it's only in hindsight that we’re able to see how much we were missing.

The brilliance of Where the Goats Are isn't in its prescribed meaning, as is the case with so many other narrative games. Rather, it's in its ability to let players find meaning in their own play, no matter what kind of play that might be. Even though my first pass was characterized by a callous hunt for cheese-backed prosperity, Memory of God's brilliant goat game is nonetheless able to produce a powerful message:

Be glad you can come back and try again.