Videogames don’t work as movies

An evil warlord is trying to raise an army of the dead and Henry, who was apparently just resurrected himself, has one remaining memory: his dad wanted him to do more punching. So he punches everyone in Russia. And he shoots them, too, and stabs, maims, and explodes everyone else in his way with as much gore as Hardcore Henry’s filmmakers could splash around. And yet it almost put me to sleep.

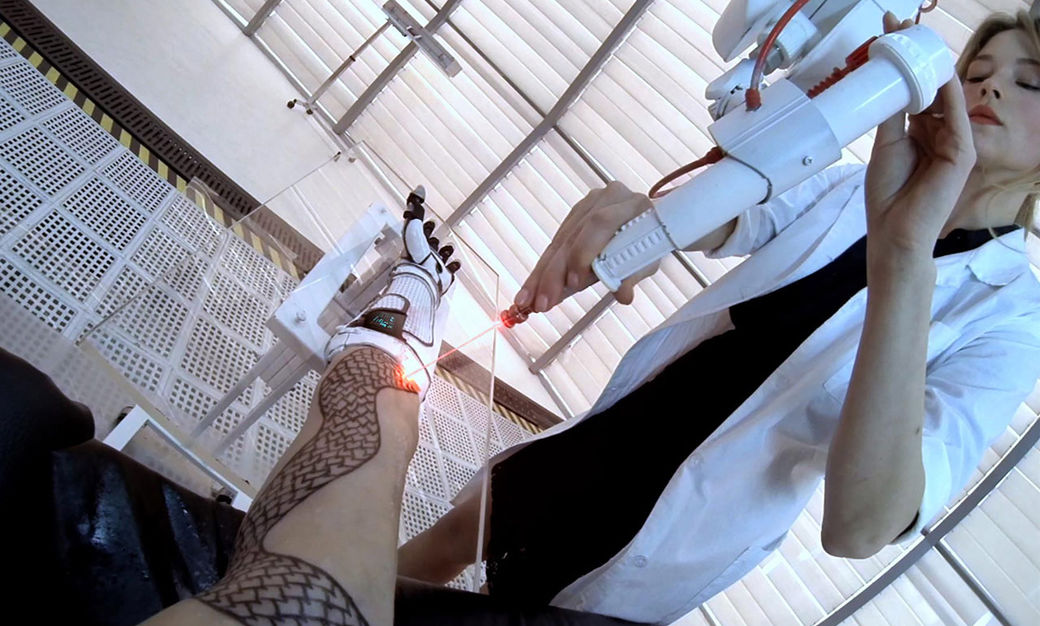

Hardcore Henry is the latest attempt to filmify the gimmicks and visual language of games. It follows in the recent, stumbling footsteps of Hitman and Need For Speed, which were both panned by critics, and deservedly so. Videogames tend to inspire films about cardboard characters who tumble around bland action scenes, advancing plots that have little to say about the world. Hardcore Henry does the same, and though it isn't based directly off any one game, it's probably the most direct answer to the question, 'What if we made a film that's like a videogame?'

That answer: something less fun than a videogame, and sleepy eyeballs. Hardcore Henry isn’t exactly a soporific film, it’s just hard to look at. It's shot entirely in first-person with GoPros, as if it were a low-framerate shooter with motion blur turned up to ‘film is the wrong medium for this, pal.’ The fights are a pulsing smear of color as viewed from the perspective Henry’s face, and the more I squinted the more I was tempted to release my eyelids altogether and just listen and dream.

Hardcore Henry isn’t exactly a soporific film, it’s just hard to look at.

Some of the practical effects by first-time film director Ilya Naishuller and crew are impressive enough to stay awake for, though: a chase scene in which Henry disembowels a van with a minigun and anything that's mercifully in slow motion. Hardcore Henry really is like a non-interactive first-person shooter—a Call of Duty, at least—and there's some fun in that. Henry is mute, and everyone’s constantly giving him instructions or guns. There’s even a grenade tutorial, as well as a sniping mission with a guy in a ghillie suit, which are such obvious, exaggerated winks at FPS players that I enjoyed them for being cute, like how my dad says "that's cute" whenever something makes a reference to something he knows. Stupider, though, are the hackneyed jokes like a break in the action so a man can make sure Henry knows he’s straight (because Friends didn’t spend enough time on gay panic episodes) and the obligatory giggling prostitute orgy, just like in the games.

I did enjoy the broad strokes of Hardcore Henry's story. It’s dumb and says nothing significant about anything, but the two scenes that build narrative are fun: the introduction which births Henry and plays a neat trick with the setting, and when Sharlto Copley does a song and dance routine to I’ve Got You Under My Skin to demonstrate the film’s best sci-fi premise.

But remember when Gamer did a dance to the same song? Hardcore Henry takes from its contemporaries and only gives back eye strain. I dig the style of modern action flicks where there’s a shot clock for kills, but Crank, Dredd, The Raid, and John Wick all captivate while Henry silently shoots guys who keep coming down the stairs for some reason. Stop running down the stairs, guys. Henry’s going to shoot you.

There’s very little tension, with no memorable scenes that wind up slowly and snap like Inglourious Basterds’ pub scene or when Dredd says, “Let’s give them the good news,” and rolls a grenade into a tight shot of feet. The attempts at humor are limp and Henry’s inability to react to his own killing spree makes it feel meaningless and flat—like in many of the videogames it emulates. A lot of Hardcore Henry’s problems are the same problems games run into, really. How do you choreograph incredible action when you’re limited by what the player can actually do, and in this case, what the viewer can process and stomach? If you're not Resident Evil, how do you create tension when you don't have control over the camera? And how do you tell a great story when the player or viewer is inhabiting the body of an amnesiac husk?

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

If Henry's amnesia and the first-person perspective were meant to make me feel like I was Henry, it didn’t work. I felt like I was a GoPro strapped to the forehead of a stunt actor. And it might seem like that’d be cool anyhow, but it’s not really. Not for 90 minutes. It’s tiring to watch and the novelty doesn’t end up being more exciting than tradition. If I were watching a Tony Jaa film, for instance, I’d want to see Tony Jaa kick ass from the perspective of someone watching Tony Jaa kick ass, not whizzing around from the middle of his forehead.

‘Being’ Henry just meant watching a film in which protagonist is nobody, and that isn't just because of the perspective. He’s given little time to touch his face, look in the mirror, or do any of the sorts of things someone might do if they’ve woken up with amnesia. It refreshed in my mind the thought that silent, ‘blank slate’ protagonists aren’t often the most fun storytelling vehicles, even though we’ve made them videogame deities.

I never imagined myself being Gordon Freeman in Half-Life 2, for instance. How could I be Gordon when Gordon is nothing, nobody? He’s a face on the boxart with a thin backstory. It’s only the interactivity—the sense that I can affect the characters and world—that connects me to the events, but at best I feel like an emotionless, stoic outsider on a tour of someone else’s world. The feeling’s there in Portal, too, and it effectively evokes isolation, unease, and lets the writers make jokes at the player’s expense, but the silent protagonist doesn't know many other tricks.

Mercifully, Hardcore Henry isn’t in 3D, and the seats don’t rotate.

The Metal Gear series conflates player and character in a more inventive way by breaking the fourth wall and referring to both the player and Snake by the same name (Matthew Weise has written a great persuasive article on that topic). Give me a character who belongs in the world and then convince that his or her desires are my own, and I think you've done something more interesting than put me into an empty body, but I'm not totally against the Gordon Freemans of gaming. I can relate to their worlds through interaction, by being that cool outsider who has nothing to say but lots of shooting and physics puzzles to do. When people start talking into my face in a movie, though, I just feel like I'm at a theme park attraction, holding 3D glasses to my face while the chairs jostle around. Shrek's there.

Mercifully, Hardcore Henry isn’t in 3D, and the seats don’t rotate. It’s just semi-watchable gory violence about nobody. It’s fun for some of its technical stunt achievements, but I don’t think its perspective needs repeating unless it’s on a 144 Hz monitor with motion blur turned off. It's not that films can never take inspiration from videogames—Dredd especially is already compared to games—but there's a lot of translation required. A character designed to be interactive isn't the same character when the interactivity is stripped out, and neither is an interactive action scene, or a perspective. A film that prioritizes game language over film language just results in a bad film and an even worse game.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.