The story of Dear Esther

During the summer of 2008, a Half-Life 2 mod changed the way I thought about games. Developed as part of a research project at the University of Portsmouth, Dear Esther featured no shooting and no puzzles. Instead, it simply presented a Hebridean island for you to explore, and an unusual story of motorways and science experiments that fell into place as you did so.

Almost three years later, that humble mod has been signed by Valve for a full, standalone commercial release on Steam. It's been rebuilt in its entirety by Robert Briscoe, one of the team behind the stark and strikingly memorable environments of Mirror's Edge. And it's stunning. The Source Engine – now more than six years old – has never looked so beautiful.

I've played through a good chunk of the second take on Dear Esther, and it's shaping up to be even more fascinating than the original. But almost as interesting as Esther's story is the story of the game itself, and how it came to find itself on the cusp of a commercial release.

The Dear Esther concept began in 2007, emerging from a research question proposed by Dr Dan Pinchbeck of Portsmouth University. Pinchbeck wanted to see what would happen were a game to focus purely on storytelling, to the exclusion of more traditional interactive elements. He also wanted to see how people would react if a closed reading of that story were near enough impossible to reach.

“Esther is basically about ambiguity,” he explains. “It came from this idea that you could do more with storytelling in games if you stopped worrying about everything making sense and adding up, and that when you read a book or watch a film, you are filling in a lot of those details yourself. Games are like films in that regard: you have these cardboard cutout sets and no one worries about that – we focus on the front, not the back. So we can apply a similar thing to story, and stop giving as much away.”

Funded by a grant from the Arts & Humanities Research Council, Pinchbeck and his team set about creating a Half-Life 2 mod to explore his ideas. In Dear Esther, you play an unseen, nameless protagonist, wandering through the mist, triggering randomised audio clips of letters being read aloud to a woman named Esther. It's not clear who she is, nor how you and she are related. But as you make your way towards the island's peak, a haunting story begins to clunk together.

“Grief, loss, guilt, faith, illness,” says Pinchbeck, when I ask about his interpretation of the Dear Esther story. “Cheerful stuff. But it's also – and this is really important to me – about love and hope and redemption, and how people cling to each other in the face of a brutal, uncaring world.”

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Dubbed 'an interactive ghost story', Dear Esther is never overtly scary. Instead, it builds atmosphere and an emotional weight. The audio clips tell you about the island's history while simultaneously documenting a terrible accident back home in England. But it's also a character story. You learn of a syphilitic shepherd, an explorer whose infected injury sent him insane, and a man destroyed by guilt after a fatal car accident. They blur together. Depending on how you read it, they might not even be three separate people at all.

The island itself is no less intriguing. Phosphorescent paint splashed on walls. Chemical equations etched into the sides of a cavern. Enormous chunks cut out of a cliff face in perfectly straight lines. Bible verses scrawled all over the island, and a flashing radio tower omnipresent in your view.

Exploring a spectrum of moods within the medium of games is something Pinchbeck takes very seriously.

“It's important that we all keep pushing at the potential emotional range of gaming and how subtle we can make a player's emotional journey,” he says. “What I hope about Esther is that although it is fairly dark, there are subtle tones to that: an ebb and flow that makes it an interesting journey that we can all recognise, rather than just us standing there hitting the player with the tragedy hammer until they give in.”

But right at the centre of Esther's story is the idea that there's no absolute interpretation of the themes at play. Pinchbeck expected that this may turn players off, leaving people bored and unfulfilled. He was spectacularly wrong. Instead, Dear Esther became an indie darling, downloaded more than 60,000 times, enthused about by the gaming press, and honoured with an international award.

A year later, fresh from a stint on Mirror's Edge, a level designer showed up.

After an exhausting couple of years working in Sweden, Robert Briscoe returned to the UK, having decided to take some time out to recuperate. He'd originally planned to use this time to work on a small prototype he'd been tinkering with – a zombie-filled survival horror mod built in the Source Engine. But then came an attack of the undead, as wave upon wave of brainmunchers saturated the PC games market. Not wanting his idea to be lost in the crowd, Briscoe put his project on hold.

This left him with a year or so to burn. Searching for ideas, he turned to the premier mod site ModDB for inspiration – and stumbled upon an unassuming little release called Dear Esther.

“It was the inspiration I'd been looking for,” he recalls. “A simple, highly original idea which was singularly focused on telling a story through the environment. It stuck in my mind for days afterwards, and although I toyed with the idea of translating Dear Esther's core mechanics to my own designs, I couldn't shake the feeling that there was so much untapped potential in the original, if only for a proper coat of paint and a more polished design.”

For Briscoe, Dear Esther's main weakness was the island itself. The story was fascinating, the ideas great, but the island worked against the game: players were getting lost, or stuck, or bored.

“One of the most common complaints about the original was the tediousness of trudging through the simplistic landscape between audio cues and landmarks, which made exploring rather unrewarding,” he says. “To be fair, it wasn't really a failing of the design per se, but a shortcoming of the Source engine and how it handles large outdoor environments.”

Having worked with Source for over five years, Briscoe had a few tricks up his sleeve to bring the concept to life. “It allowed me to create a much more rich and detailed world than ever attempted before in the engine,” he explains, “which encourages and rewards exploration with the incentive of uncovering small clues and details about the history of the island, its inhabitants and our protagonist.”

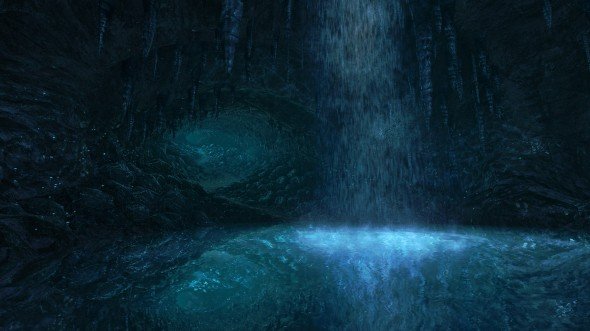

The remake pushes the Source Engine to places it's never been before. Realistic waterfalls cascade down the walls of extraordinary caverns, gleaming bright blue in the phosphorescent light. Outside, foliage sways and leaves blow in the breeze, as the moon forms a striking reflection on the eerily calm ocean. The picture painted by Dear Esther is as vivid as any in gaming.

“The visuals are going to have a massive effect on how immersive the island is, and that's really important,” says Dr Pinchbeck, who afforded Briscoe a great deal of freedom while rebuilding his game. “There's a lot of subtle stuff going on in there, and what's really cool is how Rob has responded to the original version and put his own spin on stuff. I sent him pages of notes, and I've been looking at alphas and feeding back, but right up until the deal with Valve happened it was mainly Rob's gig.”

It was quickly obvious that this was going to be more than a simple graphics overhaul. With his level design techniques, Briscoe had transformed the world of Dear Esther into something remarkable: a game whose world was its primary character, and where every landmark told its own story. “There's quite a bit more focus on exploration, properly rewarding the player for leaving the obvious path,” says Pinchbeck. “And the great thing about going indie is that we've been able to do all of that – to make it more than just a visual overhaul.”

Until fairly recently, the Dear Esther remake was still set to be released as a free Source mod. But that changed when Pinchbeck and Briscoe decided to approach Valve with the view to licensing their engine to release a fully fledged indie game. Valve were impressed. They agreed, and signed Esther as a Steam exclusive.

It was Pinchbeck who originally suggested the idea. “My reasoning behind it was that Rob was creating something so extraordinary, it deserved a wider audience than we could give it as a mod,” he explains. “I love the mod scene, but it is limited in terms of reach.”

Pinchbeck had another agenda in mind, as well. Esther was originally created as part of a research project at the University of Portsmouth, and one of that project's pillars was that its games should function as actual, playable titles that the community could respond to.

“I think games researchers have this amazing opportunity to explore high-risk areas of game design, and we have almost an obligation to run with ideas and push them as far as we can. We started off saying 'will this work as a game?' and the answer was pretty resolutely 'yes'. So the next question is, 'what happens if you commercialise that?'”

If it works, then in theory Pinchbeck and co could find themselves in a position where they can fund their next experiment with their earnings from the last one. “Which is massive,” he says. “We're doing something that has actual, absolute relevance to the industry, and we're proving it has value – not in some obscure journal, but out there, in the marketplace.”

It will be interesting to see how the wider gaming community reacts to Dear Esther. It's slow, uneventful and pondering, and only an hour long. Robert Briscoe has struggled to describe Dear Esther during the 18 months he's been working on the remake. “I often find myself avoiding the word 'game',” he says, “preferring to describe it as more of an experience or story. I always want to ask people if they've ever stared at a painting and wondered what the story was behind it, or imagined being able to transport themselves through that small window into the world and explore it. Most people connect with this.”

For Pinchbeck, this indicates a newfound maturity in gaming. “I think we've been in an amazing period of creative expansion in games for a couple of years, and that ranges right from really left-field independent titles to mainstream AAAs. There are so many great titles and developers out there, and some really experimental work finding a place in the market. Games get a lot of stick for being derivative, but the reality is that it's one of the most amazing mediums on the planet in terms of the audience actively demanding innovation, and being happy to fund that themselves.”

Perhaps the most interesting comments come from composer and sound designer Jessica Curry. She's currently in the process of re-orchestrating Esther's entire soundtrack: as Briscoe has done with the environments, Curry is rebuilding the audio from the ground up.

“I'm not a gamer, or from that world at all,” she says. “So I've always seen it as a piece of digital, interactive art. Dan sees it as a game, but neither of us really think you have to make the distinction. For me, art is about an experience which touches people deeply. I really think, and hope, that Dear Esther achieves that.”