Stellaris: how Paradox plan to make an infinite grand strategy

As of last February, the average playtime of Crusader Kings 2 was 99 hours. The longest individual playtime was 10,500 hours. Paradox's grand strategies are large, complex affairs, but I'm not convinced there's enough variety in their historical sandboxes to keep things fresh over that many hours. Stellaris is Paradox attempting to create a game that justifies their fan base's strategy obsession. Its systems are designed to ensure that every campaign offers something new and surprising.

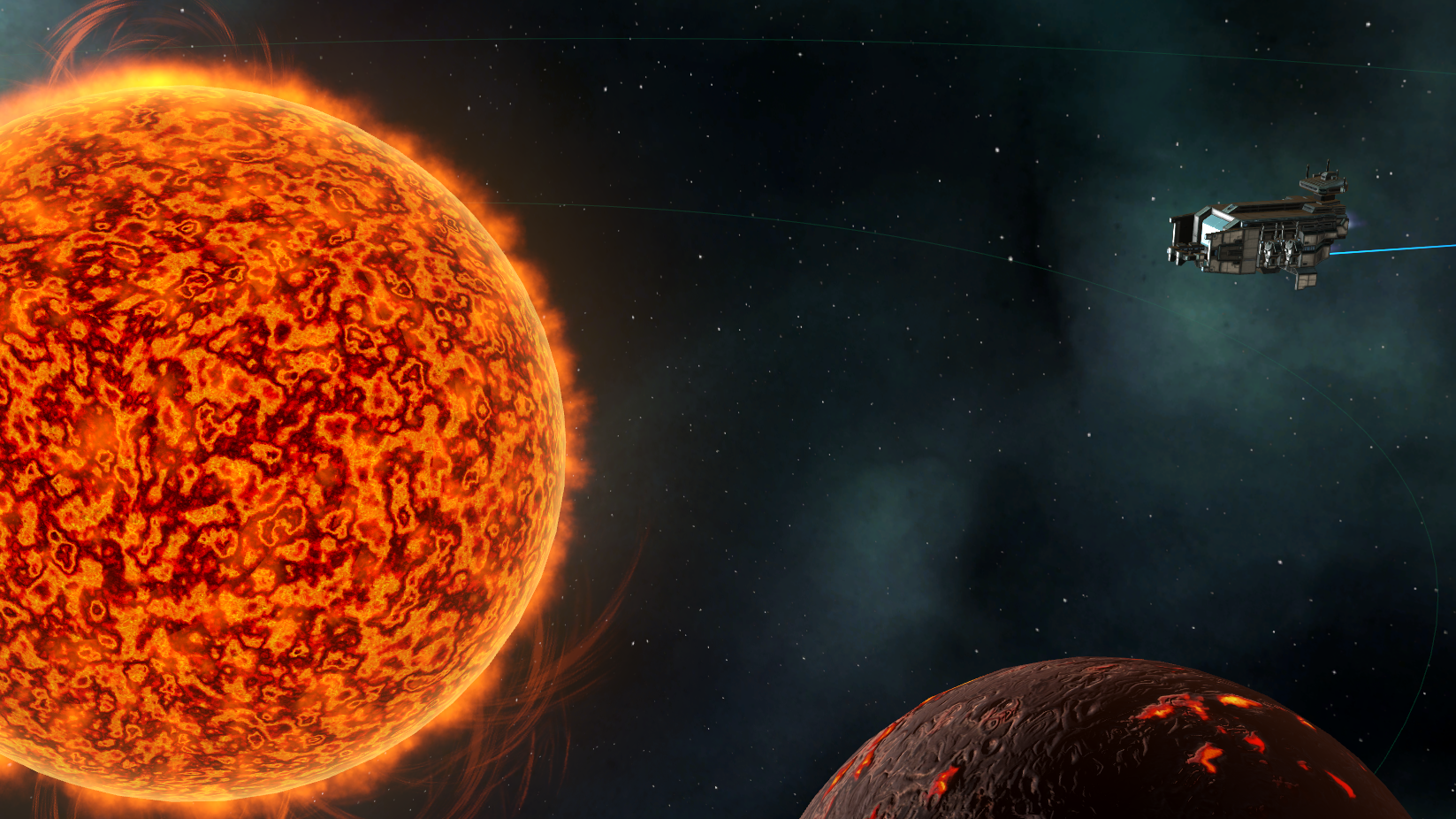

"It's a radical departure, but in some ways it's still the same," says Paradox Development Studio director Henrik Fåhraeus. There are some definite similarities between Stellaris and the studio's previous grand strategies. It's still a pausable real-time game, for instance, with the option to speed up and slow down the passage of time. It still runs on Paradox's "tried and true" Clausewitz engine—the underpinning technology behind every PDS game since Europa Universalis III. There are, however, some differences too. For one thing, Stellaris is set in space.

Its systems are designed to ensure that every campaign offers something new and surprising.

The setting is more than just reskin, but a chance for Paradox to break from the rigour of historical accuracy and give players—and their opponents—more scope to define their empire. While the character creation screen I'm shown contains roughly 100 portraits for different alien races, the tools for creating an empire are virtually limitless. In addition to your empire's look, you'll also be able to define its traits, technologies, ethics, and even how FTL travel will work. The AI will do the same, ensuring you have no idea who's lurking beyond the range of your sensors.

Many of these early choices will affect the actions available to players in-game. Create a xenophobic empire, Fåhraeus explains, and you'll be able to capture aliens and use them as slaves. Found a xenophilic empire, and you won't have that option.

The early-game stage is comparable to a 4X, says Fåhraeus. Here, you'll be exploring, discovering and expanding your empire. Each planet in your empire is governed by an individual character, with their own personality traits and skills. They'll determine much of the what happens on each planet, sometimes without your direct intervention. In a way, this focus on individual characters makes empire management akin to Crusader Kings 2—despite the fact that diplomacy between empires will be more comparable to Europa Universalis 4.

Each colonisable planet will have an abstract map upon which you can construct buildings. You'll be rewarded for placing same-type buildings next to each other, and can assign a planet's "population units" to various jobs based on what you've built. There'll also be special tiles, and, according to Fåhraeus, some of the procedures for clearing them will be "rather involved." The example given is a Giant Sinkhole. It's a big hole in the ground that, not only prevents buildings from being placed, but—at some point in the game—could let subterranean creatures pour out onto the surface.

As a sci-fi game, science has a much bigger role than any previous Paradox strategy. Scientists, like planetary governors, are individual characters with their own traits, specialities and lifespan. They'll be able to head up science ships—sent out to explore and survey other systems in search of anomalies. In the presentation, a science ship comes across a hollowed-out asteroid that triggers a choose-your-own event chain. If it succeeds, there's a chance to earn new technologies. If it fails, a number of things can happen. Best case: nothing. Worst case: the asteroid is knocked out of orbit and onto a direct course with your home world.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Fåhraeus explains that different things can happen based on the scientist's personality. If a religious character had discovered the asteroid—actually a hollowed-out temple to a human god—they could potentially have an option to destroy the heretical monument. These unique conditions are designed to create unexpected outcomes for events the player has already encountered in previous campaigns.

Phil has been writing for PC Gamer for nearly a decade, starting out as a freelance writer covering everything from free games to MMOs. He eventually joined full-time as a news writer, before moving to the magazine to review immersive sims, RPGs and Hitman games. Now he leads PC Gamer's UK team, but still sometimes finds the time to write about his ongoing obsessions with Destiny 2, GTA Online and Apex Legends. When he's not levelling up battle passes, he's checking out the latest tactics game or dipping back into Guild Wars 2. He's largely responsible for the whole Tub Geralt thing, but still isn't sorry.