In advance of next week's PC Gaming Show, a few of our participants are sharing their perspectives on PC gaming and game development. Today, Adam Saltsman, co-founder of Finji, currently developing survival strategy game Overland, writes about the challenges of finding the right set of tools to run a public alpha.

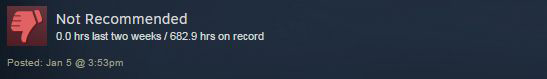

Here's one of my favorite memes from the last year or so:

For a lot of players and developers, reviews like this have become a running joke, usually about entitlement or millennials or something. The big red thumbs-down combined with the high number of hours played is pretty silly at first sight.

Having paying players that are passionate about your game and providing feedback before a wide release can be an invaluable resource.

There's a lot more to it than this, though. Most of these high-hours, thumbs-down posts are actually from passionate supporters of the game. They're trying to do their best to give an accurate review of the game in its current state. And for games that are still in alpha or that are just very niche, it can be hard for an honest and intelligent player to recommend that game to a general audience based on their experience. Most players really aren't up for spending loads of time with games that crash, destroy their save files, or have incomplete UIs. Weird, right?

For developers, though, having paying players that are passionate about your game and providing feedback before a wide release can be an invaluable resource. Right now, Steam Early Access is struggling to balance these two tricky dynamics: allowing developers to reach out to truly adventurous players, while simultaneously offering these games for sale to their wider audience.

We needed a way to make sure that we only got a trickle of players at first, so we could test things out properly before opening the floodgates.

In ye olden days, developers just ran their own alpha or beta programs. Many still do—Don't Starve, Prison Architect, Spy Party, and Factorio all ran or are still running significant off-Steam alphas or betas. There's some significant engineering overhead involved though. As a developer it's easy to end up spending a month or two setting up payment processing and an efficient system for sending gameplay patches to players (two things that Steam automates very successfully).

Maybe I should introduce myself though. My name is Adam Saltsman, and my partner Bekah and I run a little mom-and-pop indie label called Finji, where we make and publish new games from new teams. Before this we worked on a bunch of different stuff like Canabalt, Capsule, Hundreds, and Dikembe Mutombo's 4 1/2 Weeks to Save The World. We also helped out some with Cave Story+, FEZ, and some other things. Right now most of our time is spent working on Overland and Night in the Woods.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Last fall, as we were preparing for Overland's paid alpha, we started talking to every platform we could about the potential for alternative approaches to running public alphas. We were looking for a handful of features that we thought would be good for us as a developer but also good for our community:

Automated Uploads and Patching: Uploading and downloading a few gigabytes of game data several times a week is a really good way to blow out your data cap. It's also just plain slow. Sometimes we do two builds a day—we needed a way to get updates out quickly and easily.

Access Control: We had (and still have) concerns that parts of Overland are not ready for the harsh spotlight of a mainstream audience yet. A mix of content and design issues mean that while the game has a strong following now, it needs a little more time in the oven before most folks get their hands on it, if it's going to make its best first impression. We needed a way to make sure that we only got a trickle of players at first, so we could test things out properly before opening the floodgates.

Fair Revenue Share: I'm not sure how much this is talked about publicly, but most online game stores keep roughly one third of every game's sale price. Even for indie games, this is a larger cut than any of the team members actually making the game can expect. But imagine if every game's budget went up by at least 20%—that's good for devs, and great for players. Yes, for a wide release where developers are taking advantage of a store's large built-in audience, the tradeoff can absolutely be worth it. Our years on the iTunes App Store made that very obvious! It's not as clear how it's a fair split for a quiet alpha though.

There are other features that were important to us—avoiding a confusing user reviews system, setting up a community that was private to the actual owners of the game, access to a modern backend, etc. But these were the big three, and no existing store offered anything like this. It looked like we were about to make some pretty significant investments so that we could just build our own system from scratch.

Then along came Refinery, a new open-source toolset from the alt-games storefront itch.io, which does all these things and more. Thanks to the official itch.io app and command line uploader, most of our patches are about 1-2% of Overland’s total download size. I can list any of our games for any price I want, with granular control over page visibility, and set up special rewards and support tiers. I can even limit the number of copies that are available to help us manage the rate at which the game grows. And nobody needs to approve these decisions—there are no gatekeepers.

Revenue sharing is opt-in on a per-developer basis, so we decided on a percentage that we thought was fair. We can change this at any time depending on our needs and plans. This way we can support itch.io and reinvest more of the revenue into the game itself. Itch.io also has private message boards for the Overland players where I can field bug reports, talk about gameplay and feature suggestions from the community, post change logs, and so on. These tools completely changed the way we were able to enter our paid alpha phase of development, without the engineering overhead of reinventing the wheel for the 300th time.

This is a very good trend for PC gaming in general—the more stores there are that can support a healthy environment for things like public alphas, the better our games will be when they find their mainstream audience. I would love to see other platforms, stores, and communities add support for these features too. When stores empower developers to grow their audience in the way that best suits their particular game, everybody wins.

The collective PC Gamer editorial team worked together to write this article. PC Gamer is the global authority on PC games—starting in 1993 with the magazine, and then in 2010 with this website you're currently reading. We have writers across the US, UK and Australia, who you can read about here.