Here’s the most tragicomic thing that has happened to me since I started playing Overland. My crappy hatchback lies abandoned on a country road with a couple of gallons still in the tank. Its human inhabitants are dead, picked off by scuttling insectoid creatures. I’m able to keep playing because the dog I befriended on an earlier level is still alive. The dog can pick up gas cans with its mouth, but for obvious reasons isn’t able to fill up the car or drive it. It is however able to befriend another dog that’s wandering around, which gives me two dogs. I click my beautiful, bushy-tailed companions around the map for a couple of turns before they also succumb to whatever these monsters are. It’s tragic because, hey, who doesn’t like dogs? And it’s comic because this is how breathtakingly mean Overland is.

I first encountered Overland when I saw a developer from Bioware tweeting about how much he loved the art style. And, sure enough, it’s gorgeous—each level is a gridded square that looks like a little isometric diorama drawn in the kind of graphic art style Olly Moss applied to Firewatch, only simpler and cleaner. You almost want to reach into the screen and pinch up the characters to move them around rather than use the mouse. The game is being developed by Austin-based Finji, which previously made Canabalt, and is run by husband and wife team Adam and Rebekah Saltsman. I met with them at GDC last week to play Overland, and haven’t stopped playing since.

The game bills itself as a road trip through a ruined continent...

It’s a roguelike turn-based strategy game that’s fundamentally about scarcity, both in terms of time and resources. You spend action points—two per character, initially—on walking around, searching dumpsters, attacking monsters and so on. Inevitably, there are rarely enough to do everything you want. The game bills itself as “a road trip through a ruined continent”, and though it’s not clear (at least, yet) why North America is overrun by these creatures, it actually doesn’t matter. You need to escape, fast, and keep escaping.

Each playthrough begins on the East Coast, with a randomly generated character and a car. There may be another person, or dog, to team up with. The items littered around, and the levels themselves, are random too. Overland also uses permadeath, assuming you don’t make it to the West Coast, though you can at least save+quit when the stress or dog grief gets too much.

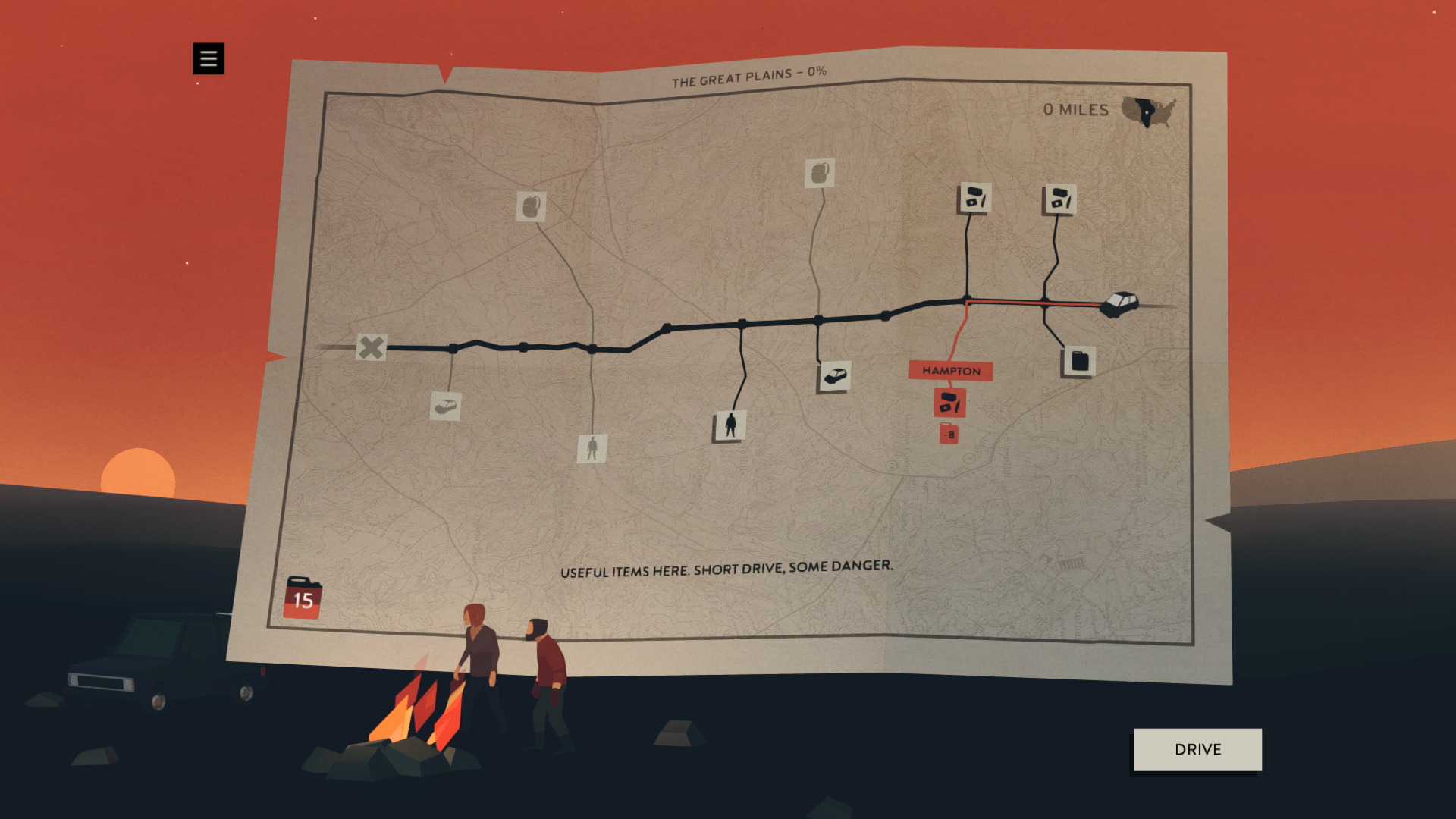

Once you leave the first level you’re taken to a map screen which shows the road ahead. Here you start making tough decisions. The map shows which towns you have the gas mileage to reach, and their potential risk/rewards. So one might be three gallons away and read: “Fuel cache. Close to the road. High risk”. An alternative could be six gallons away and say: “Useful items here. Short drive, safe.” Or, if you have enough gas and are happy with your gear, you could ignore both and push on to the next region.

The true price of gas

Make it out of a region alive and you’ll switch biomes. Woodlands gives way to The Grassy Plains, which brings the additional hazard of wildfires. “Congrats. You’ve left the kiddy pool,” Adam told me. Survive a day and there’s also a chance characters will acquire new attributes. So a person might develop “energetic” as a trait, giving them an extra action point, or your dog could become “stubborn”, meaning it won’t suffer a debuff when injured. Rolling helpful perks makes a big difference, because it’s remarkable how fast a seemingly comfortable situation can go massacre-shaped. One playthrough was going so well that I felt confident enough to make a long detour to grab extra supplies. When I arrived the place was crawling and a single poorly thought-out turn saw my team slaughtered.

Another time I lucked out on the first level and found myself with 18 gallons of gas and a dog. That was enough to skip the entire second region. The game doesn’t feature boss battles, but it does have unskippable road block encounters, triggered by entering a new region. During these you have to get out of your car and move obstacles, then make it back before the monsters (all of which are attracted to sound) swarm in. As with all the levels, the more characters you have, the easier it is to subdivide tasks. So in this instance I could send the driver to move the dumpster while the dog dashed out to grab a spare gas can.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The lumbering multi-headed monsters will turn vehicles into smouldering wrecks with one attack.

Once in the car you’re able to hightail it with a single action point, provided there’s a clear path. The further across America you make it, the more the difficulty scales up in the form of an increased number and variety of monsters. Tall spindly ones will close on your survivors quickly, while the lumbering multi-headed type will turn basic vehicles into smouldering wrecks with one attack. Which is about as bad as news gets unless there’s a spare car gassed up and ready to go nearby. Perhaps if RNG is smiling on you, the next car might have extra storage space or armor, or be an SUV or van with more room for passengers.

As you get used to the gameplay, which is quick and moreish, you become hyper-efficient about how you parcel out action points. Keeping one person in the car to move it down the road for a rapid pick up is key, especially as one of the actions you can perform is to yank a pedestrian into a vehicle, making for some dramatic rescues. In a minor concession to the player, there’s a single undo button, which mitigates the harshness of doing something like getting out the car carrying the wrong item and wasting a turn.

The combined effect is that each level feels like its own little puzzle. How do you share out actions to create the best shot at survival? And if you can’t find an obvious solution, do you pick one of the team to run distraction, knowing they won’t make it back in time? (At one point I briefly considered using a dog for this, and my girlfriend threatened to leave me if I right-clicked.) Because the levels are procedurally-generated, sometimes it can seem like you got a rough roll and it’s just too dangerous. When that happens you can duck straight out, but you’ll lose a lot of precious gas—and once that dwindles so low that you can’t reach any more towns you’ll be forced into what Adam called “a saving roll kind of level”.

These scenarios are even sterner than the roadblocks, and give you one last chance at getting extra fuel or a new car. Usually at considerable human or dog cost. Combat really is the last resort in Overland. The smaller creatures can be bludgeoned with sticks and bottles, but the only firearm is a flare gun. And in terms of alerting the monsters the only thing more disastrous than using the flare gun would be hiring a marching band.

Dog days

But as harsh as Overland is, its sense of cruelty is surprisingly fun. I often find myself saying “oh, c’mon!” when confronted with a level that looks impossible. But equally, the satisfaction when you outmaneuver the monsters and get away with a fresh haul of gas is real. There’s no release date beyond “soon”, though Adam told me the next step will be a paid private alpha for people subscribed to the mailing list (which you can sign up for here). “It’s getting there,” he said. “We’ve been working at it for a little over two years.”

After an intense prototyping phase that lasted six months, Finji has mostly been concentrating on the UI and difficulty balancing. “It’s super weird,” he says. “A lot of your moment-to-moment actions can end up being like a puzzle game, where you know you’ve got these three or four action points, you have to do several things, and the order in which you do them, and whose points you spend, become these little spatial puzzles. That’s how you can squeak back an action point, here and there, to just barely escape things.” Right now it definitely feels like there’s room to tweak the balancing to be a little friendlier, but Overland’s bedrock is incredibly solid. It's fun to play right now, and was probably my favorite thing I saw at GDC. I expect masochistic strategy fans will respond positively to the harshness. Dog lovers, maybe not so much.

With over two decades covering videogames, Tim has been there from the beginning. In his case, that meant playing Elite in 'co-op' on a BBC Micro (one player uses the movement keys, the other shoots) until his parents finally caved and bought an Amstrad CPC 6128. These days, when not steering the good ship PC Gamer, Tim spends his time complaining that all Priest mains in Hearthstone are degenerates and raiding in Destiny 2. He's almost certainly doing one of these right now.