Duskers' unseen horrors and lo-fi tech make it one of this year's best strategy games

Glowing lines have never been this scary.

Along with our group-selected 2016 Game of the Year Awards, each member of the PC Gamer staff has independently chosen one game to commend as a personal favorite of the year. We'll continue to post new Staff Picks throughout the rest of 2016.

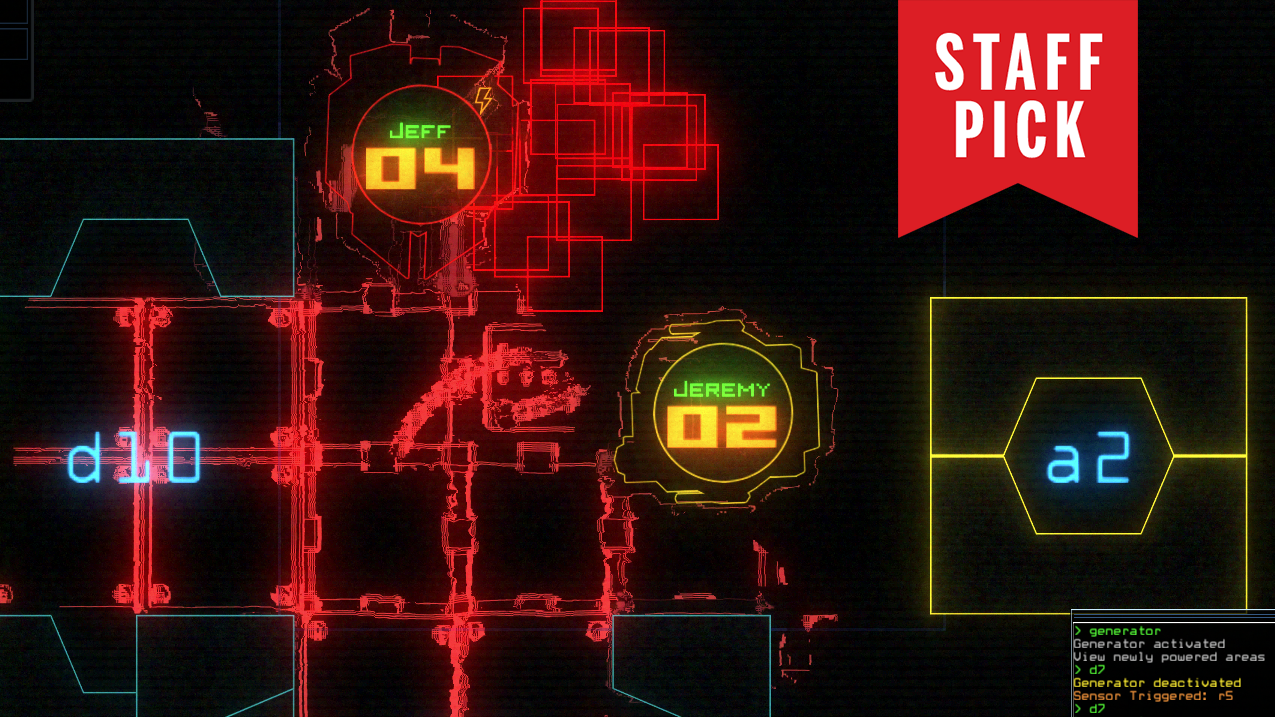

Imagine a game of chess, only you can’t see most of the board, and you don’t know how many pieces your opponent has, or where they are, or what they can do. Another small wrinkle: making the wrong move may result in your pieces being sucked into the cold void of outer space. That’s Duskers, a delightfully tense and spooky real-time strategy roguelike in which you explore procedurally-generated spaceships with a handful of remotely piloted drones. The ships contain resources like scrap metal and starship fuel you need to harvest so you can continue traveling, and while they’re devoid of human life due to a mysterious galaxy-wide cataclysm, they do host other threats.

Duskers is viewed top-down, and you can only view the immediate area around your drones, along with a map-view of the ship you’re exploring. Navigating the ships with your drones is mostly accomplished using text commands entered into a console, which gives it a charmingly lo-fi vibe. Your crackling viewscreen and some wonderful sound design makes moving deeper into the ships, room by room, an Alien-like horror experience. You can fit your drones with modules such as motion sensors and remote probes, as well as a few offensive weapons like turrets and explosives. Mostly, though, you’re playing defense: creeping slowly through the ship, never entering a new room unless you’re sure it’s cleared of threats, keeping walls and doors between your drones and the infestations, and luring or herding enemies through the sip to either contain them safely or blast them out an airlock.

There’s rarely a moment where you feel safe in Duskers, and even those moments can be alarmingly brief.

There’s rarely a moment where you feel safe in Duskers, and even those moments can be alarmingly brief. Even if you’ve located and contained every threat, there’s no cause to relax. A notification that something is chewing through a closed door means your planned route through the ship is no longer viable. Spotting a broken air vent in a room your drone is occupying means something might slither through it at any second. Even with every threat expelled or killed, it doesn’t mean you’re safe because random events such as meteor strikes, hull breaches, radiation leaks, module failures, and other impending disasters can turn a leisurely gathering mission into a frantic race to get your drones back aboard your drop ship and escape.

These moments, when a threat surprises you or a door failure cuts off your escape route or the hull fails and floods the ship with radiation are when Duskers is at its best, forcing you to improvise, think on the fly, and weigh your needs for gathering resources against the safety of your drones. When you’re low on fuel you might press your luck, taking risky routes or opening doors without knowing what’s on the other side. Other times you might take a look at the map, littered with threats and problems, and simply decide nope, that one drone in a distant room isn’t worth trying to rescue at cost of putting the rest in danger. And those times where you risk everything and still manage to escape safely, turning a complete disaster into a successful mission, are immensely rewarding. Sit back in your seat, let out a long, shuddering breath, take a moment to compose yourself, and then dock with the next ship.

Duskers is tense and harrowing experience, and it’s equally satisfying when things go your way and when everything goes terribly wrong. The dangerous alien infestations that can quickly overpower your drones means caution and cleverness are your two most effective weapons, and randomization means every game is a bit different, letting you play again and again, never knowing quite what to expect.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Chris started playing PC games in the 1980s, started writing about them in the early 2000s, and (finally) started getting paid to write about them in the late 2000s. Following a few years as a regular freelancer, PC Gamer hired him in 2014, probably so he'd stop emailing them asking for more work. Chris has a love-hate relationship with survival games and an unhealthy fascination with the inner lives of NPCs. He's also a fan of offbeat simulation games, mods, and ignoring storylines in RPGs so he can make up his own.