Our Verdict

Asus's range topping Strix B550-E board based on the 'budget 'B550 chipset isn't quite as crazy as it seems, provided you don't demand dramatic quantities of bandwidth for secondary peripherals

For

- Extensive feature set

- Nice build quality

- Top notch networking

Against

- Very pricey for a B550 board

- Stock-clocked performance is unremarkable

- Limited bandwidth for peripherals

PC Gamer's got your back

Allow me to present the Asus ROG Strix B550-E Gaming, the most expensive of Asus’ new lineup of AMD B550 boards. Nearly $300 for a motherboard based on a budget chipset? Really? If that sounds like something you never knew you needed, hold on. It’s not actually altogether crazy.

Chipset - AMD B550

Socket - AM4

CPU compatibility - AMD Ryzen 3000

Form factor - ATX

Expansion slots - 2x PCIe 4.0 x16, 1x PCIe 3.0 x4

Storage - 2x M.2, 6x SATA 6Gbps

Networking - Intel WiFi 6, Intel 2.5Gb ethernet, Bluetooth 5.1

Rear USB - 3 x USB 3.2 Gen 2 (2 x Type-A+1 x USB Type-C®) 5 x USB 2.0 (1 for audio USB Type-C)

Extras - 1x Thunderbolt header, Aura RGB lighting, SLI and CrossfireX support, two-digit debug display

Yes, the B550 is strictly the second tier variant of AMD’s latest 500-series chipsets. But it doesn’t miss out on all that much compared to its bigger X570 brother. Essentially, there’s one really significant downgrade, from which a host of detailed changes flow.

For the B550, AMD has hooked up the PCH chip at the heart of the chipset to the CPU socket via a quad-lane PCI Express Gen 3 interface. The X570 gets quad-lane PCI Express, too, but a Gen 4 interface. In simple terms, that means double the bandwidth. In detail terms, consequences for the B550 include support for just a single M.2 PCIe Gen 4 SSD running at full speed, while the X570 chipset supports two.

There are knock-on effects in other bandwidth-sensitive areas, such as USB connectivity. But in other regards, the B550 isn’t necessarily the poverty-spec choice you might expect.

With the fuller context established, what to make of this premium B550 board? At a glance it cuts a convincing enthusiast dash thanks to copious heat sinks and spreaders, including one for each M.2 slot, snazzy LED lighting, and three full-length PCI Express slots, two of which come in Gen 4 trim.

Impressively, those slots support dual-GPU graphics, each in eight-lane PCIe 4.0 configuration, ensuring the maximum currently available bandwidth for high end graphics. A niche concern? Perhaps, but it's indicative of the ambitions of this board. Similarly, the Strix B550 has not just an eight-pin but also a four-pin supplementary CPU power supply connector. Again, that’s an indication of a board designed for high performance.

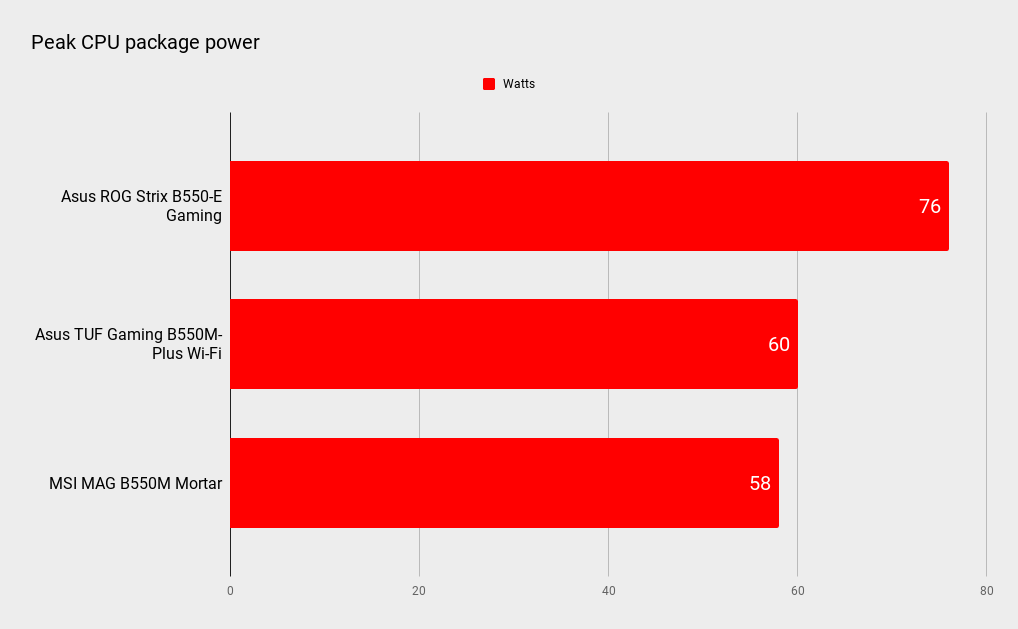

Other performance-centric features include chunky heat sinks for the VRMs (there’s no fan for the chipset thanks to the B550’s piffling 5W power draw to the X570 10W rating), a dedicated power header for an AIO water cooler pump and multiple PWM fan headers. For the record, the board is a six-layer PCB design and offers a decent 14+2 power stage.

Additionally, you get a two-digit debug display, which is nice, and 7.1 audio with shielding to reduce interface and improve sound quality. Oh, and not only an Intel I225-V 2.5Gb Ethernet controller for blazing fast networking, but also Intel Wi-Fi 6 AX200 wireless connectivity with 2x2 Wi-Fi 6 (802.11 a/b/g/n/ac/ax) support. That’s double nice with extra cheese. The aforementioned LED lighting, incidentally, can be easily synced with an ever-growing portfolio of Aura-capable ASUS hardware. So now you know.

Gaming performance

Hardware performance

CPU - AMD Ryzen 3 3100

Memory - 16GB HyperX DDR4-3000

GPU - MSI GTX 1070 GamingX

Storage - 1TB Addlink S90

PSU - Phantec 1000W

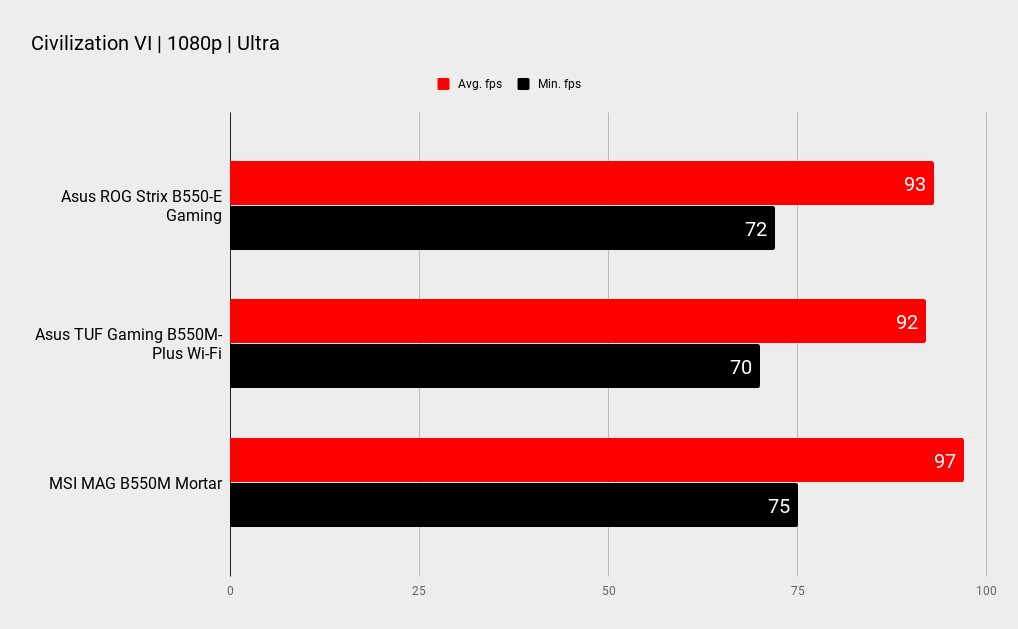

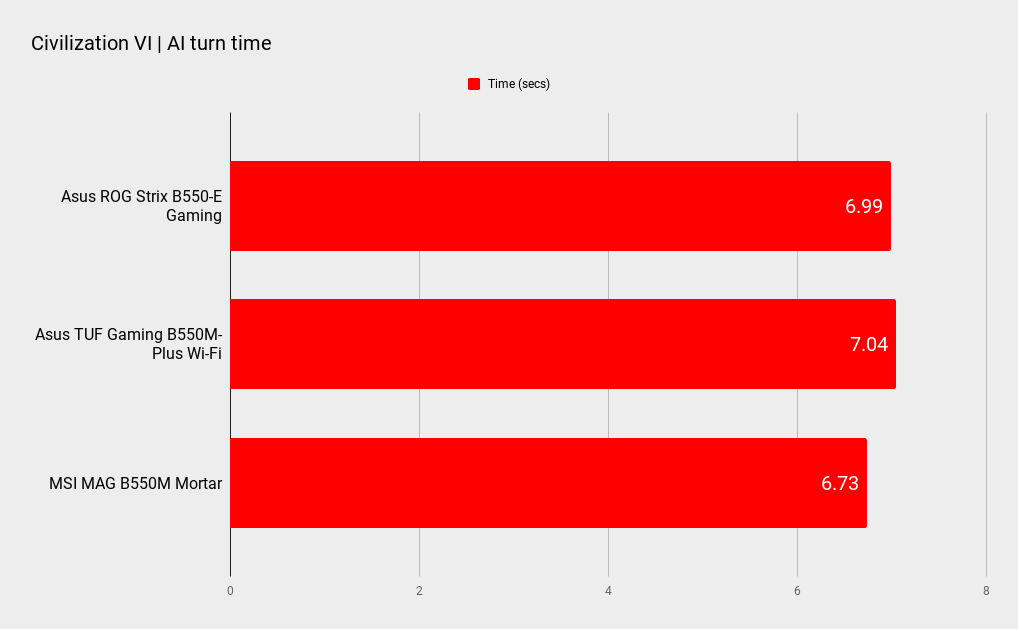

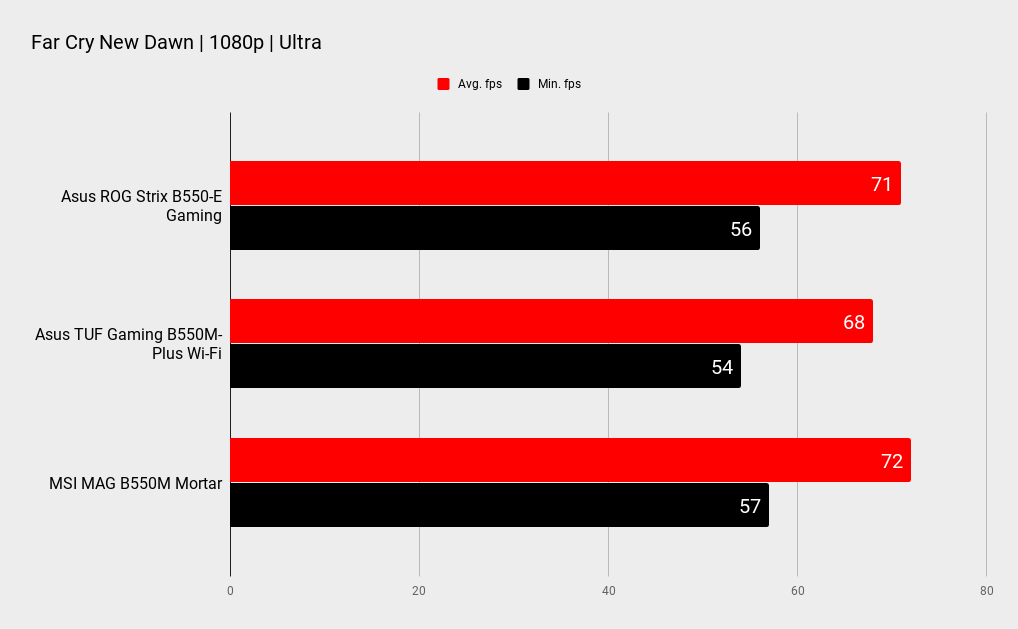

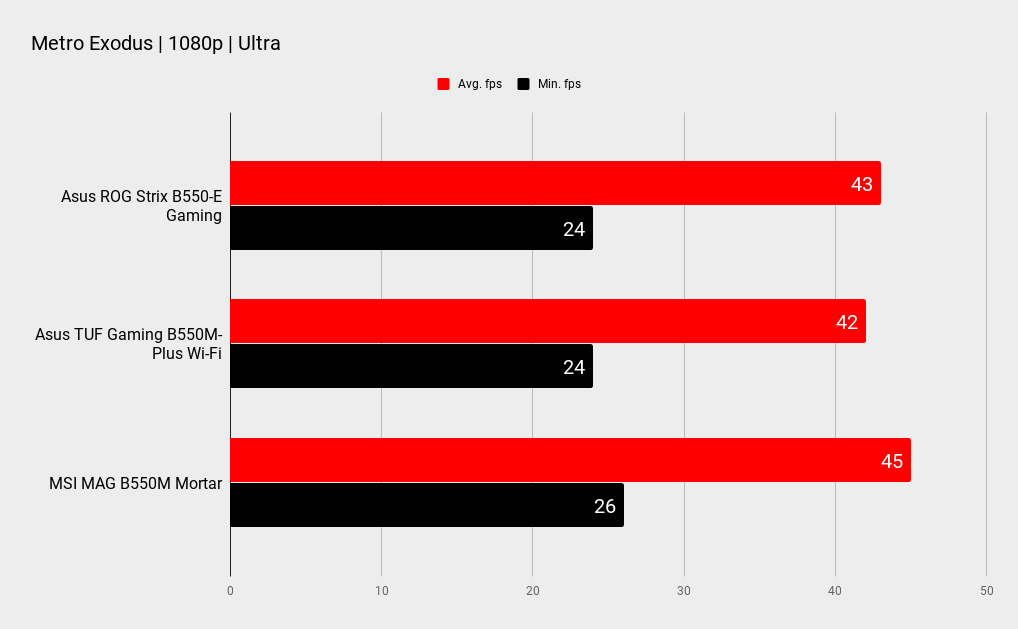

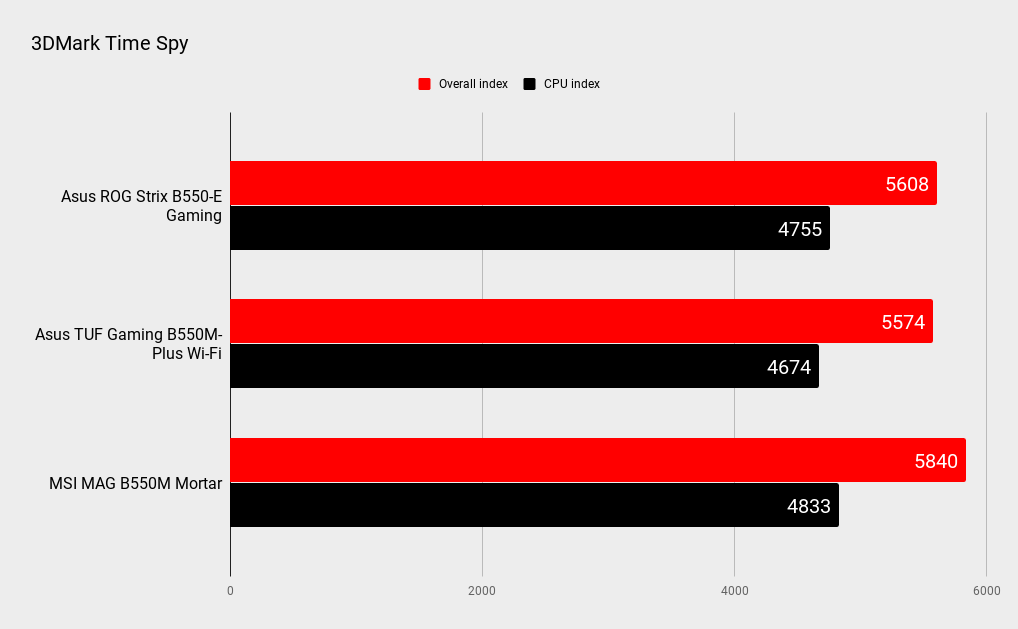

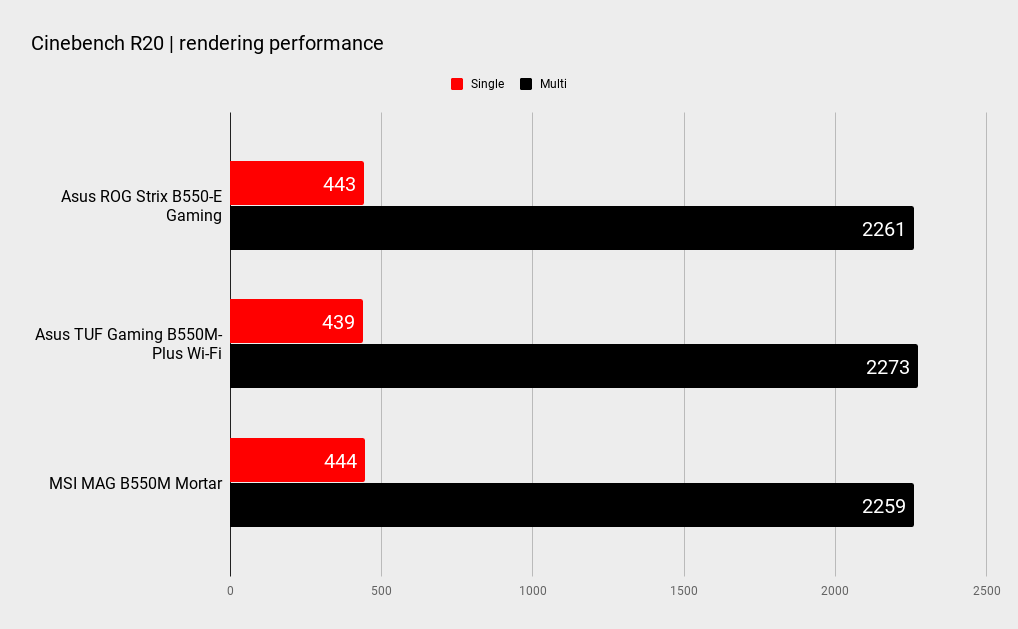

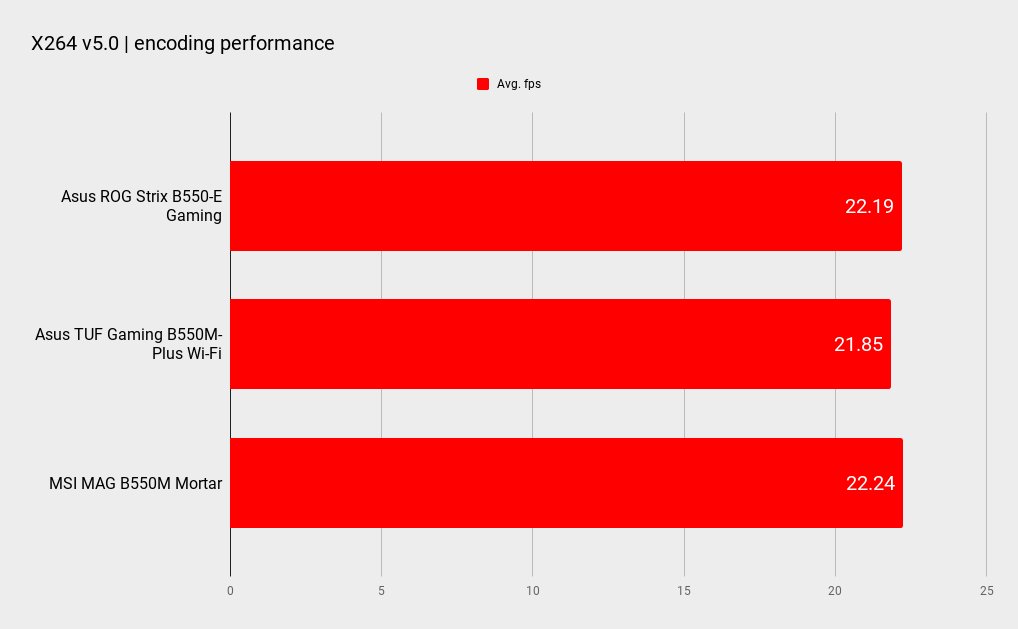

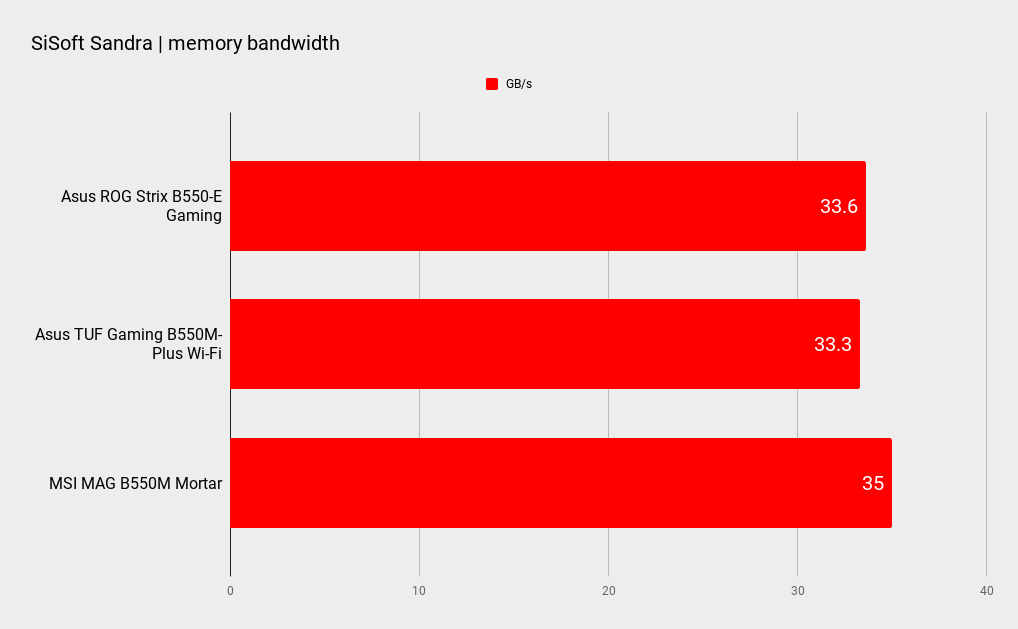

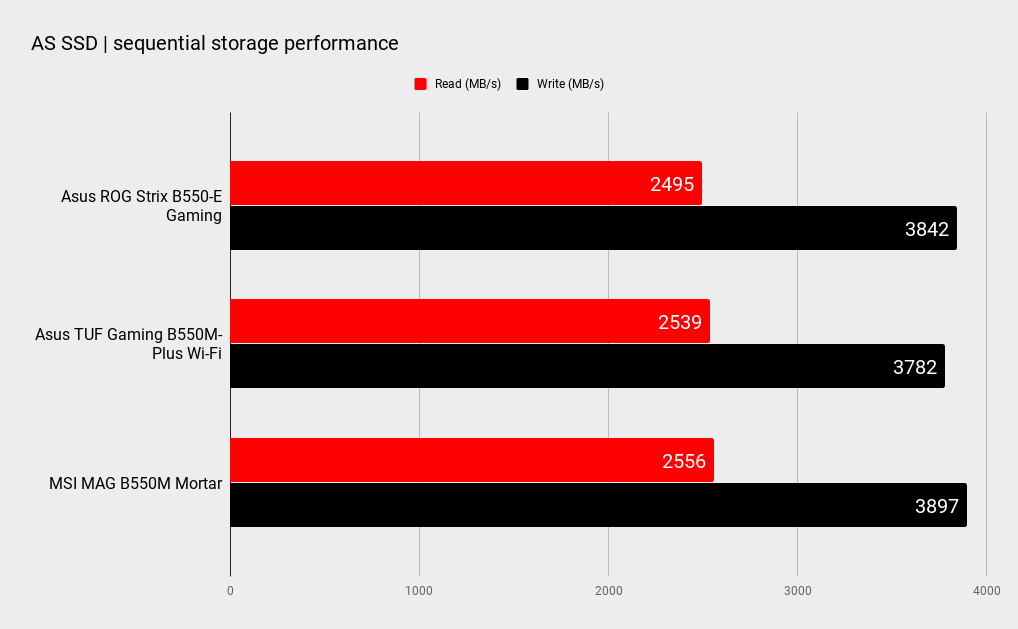

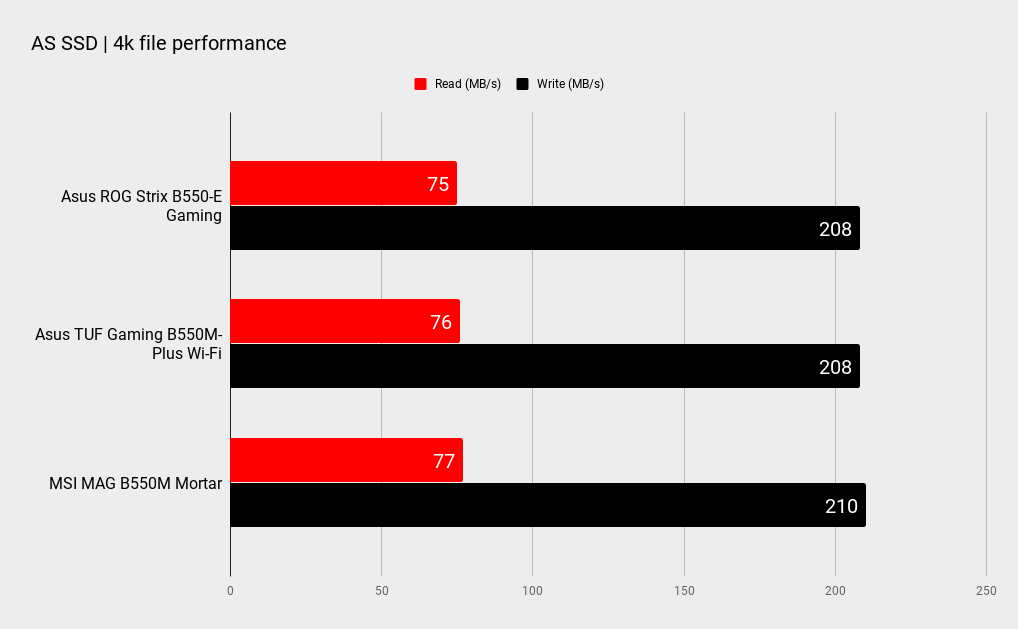

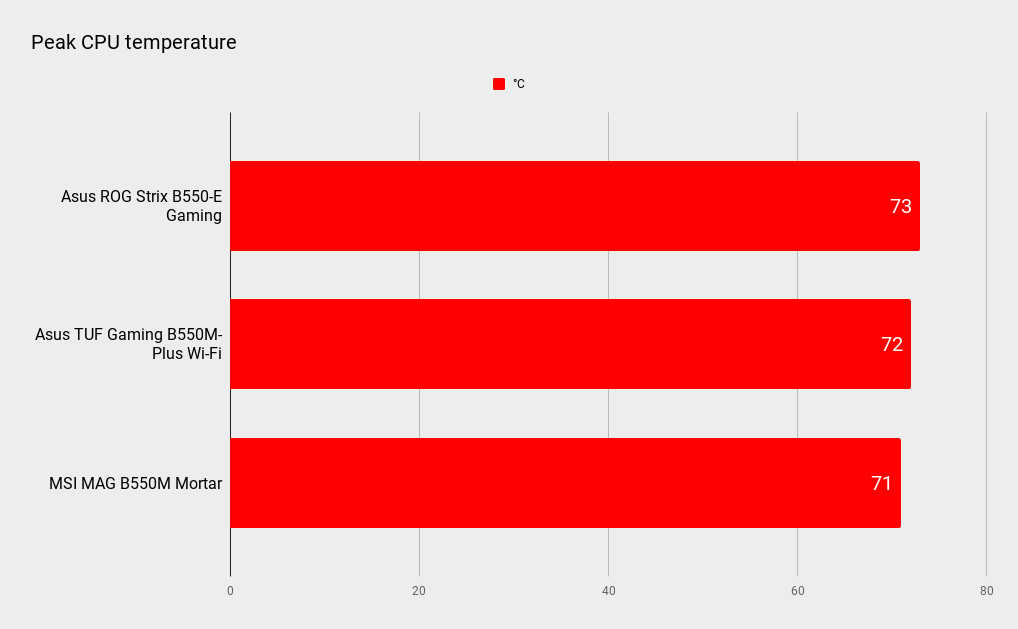

What you’ll also be wondering about is performance. Is it actually all that much better than a more prosaic - and cheaper - B550 alternative? At stock clocks and default board settings, the inevitable answer is... no. In fact, the Asus ROG Strix B550-E Gaming is a solid 50 per cent pricier than the likes of the MSI MAG B550M Mortar and tangibly slower in most of our benchmarks, including games.

Where the Strix looks stronger, inevitably, involves overclocking. AMD’s laissez-faire approach to clocking the twangers off pretty much any CPU that comes its way, by enabling access to super-simple core ratio tweaks, means you’d almost be mad not to give it a go. The Strix B550-E gets Asus’ slick and familiar BIOS interface that allows access to not only the core ratio but pretty much every setting a keen overclocker could wish for. So you have the choice of bumping the core ratios up and letting the board work out the details, or getting down and dirty with voltages and timings.

Allowing the board to do the detailed brain work results in an overclock of our AMD Ryzen 3 3100 quad-core test chip of 4.2GHz on all cores. The Ryzen 3100 is good for a 3.9GHz boost clock as standard, so that’s a 300MHz overclock. Which is significant, if not exactly stellar.

While we’re discussing the more extreme end of the performance envelope, it’s also worth noting that Asus’ DOCP (Direct Over Clock Profile) isn’t entirely successful in this implementation. It correctly detects the 3,000MHz XMP profile of our HyperX Predator DDR4 DIMMs, but hangs upon rebooting. Stable operation is possible at 2,866MHz, which isn’t a million miles away. But Asus’s DOCP doesn’t quite deliver on the advertised aim, which is a roughly equivalent experience to Intel’s XMP profiles.

All of which means that we’re back where we started. If maximum bandwidth for peripherals attached to the chipset is critical for you, then no B550 will serve you well. On the other hand, if you're expecting to run a pretty lean system with a single M.2 drive and not all that much by way of added peripherals, you might well decide there’s no point on paying the premium for an X570 board. You can spend the money saved on a slightly faster CPU or graphics card and still have a pretty high-end, and full-featured motherboard.

Asus's range topping Strix B550-E board based on the 'budget 'B550 chipset isn't quite as crazy as it seems, provided you don't demand dramatic quantities of bandwidth for secondary peripherals

Jeremy has been writing about technology and PCs since the 90nm Netburst era (Google it!) and enjoys nothing more than a serious dissertation on the finer points of monitor input lag and overshoot followed by a forensic examination of advanced lithography. Or maybe he just likes machines that go “ping!” He also has a thing for tennis and cars.