Our Verdict

Asrock's new motherboard is a better fit with the B550 chipset's value-orientated positioning. Performance is on par with much more expensive boards, but connectivity and expansion is limited.

For

- Affordable price

- Good all-round performance

- Has the really critical features you need

Against

- Limited expansion

- No USB-C

- Four-phase power

PC Gamer's got your back

Our first look at AMD’s second-tier member of its new 500 Series of chipsets, the B550, involved some fairly premium priced boards. Then came the Asrock B550 Taichi, a $300 beast of a B550 motherboard. Arguably, it was all getting a bit silly. Now Asrock is back but this time with B550 option that’s much more what we were initially expecting. Will it make it into our best B550 motherboard guide? Let's find out.

Chipset - AMD B550

Socket - AM4

CPU compatibility - AMD Ryzen 3000

Form factor - Micro ATX

Expansion slots - 1x PCIe 4.0 x16, 1x PCIe 3.0 x4

Storage - 1x M.2, 4x SATA 6Gbps

Networking - Gb ethernet

Rear USB - 4 x USB 3.2 Gen, 2 x USB 2.0

Other rear ports - HDMI, DVI, VGA, PS2, audio, microphone

Price - $80 / £80

Give it up, therefore, for the Asrock B550M-HDV. Clocking in around $80, it sits rather more comfortably with the value-orientated B550's market positioning. Not that the B550 is a bum chipset. In fact, it isn’t miles away from its bigger X570 brother by most metrics. The key differentiator between the two involves the link between the CPU and PCH chip, the latter essentially being the motherboard chipset thanks to much of what used to be chipset functionality now residing on the CPU package. For the B550, that link is composed of a quartet of Gen 3 PCI Express lanes. The X570? It’s also quad-lane, but Gen 4 spec and so double the bandwidth.

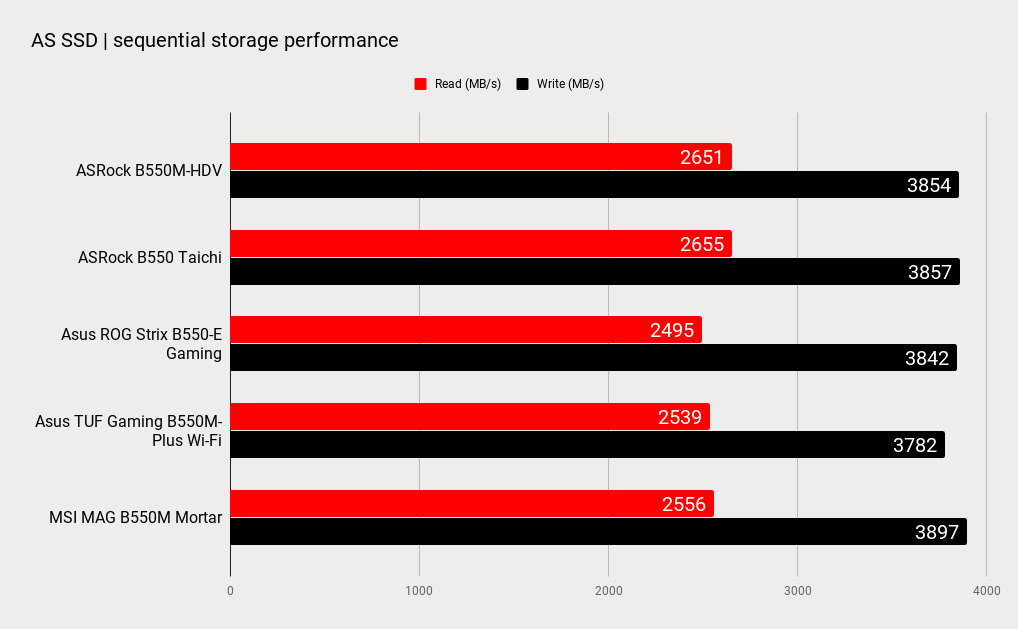

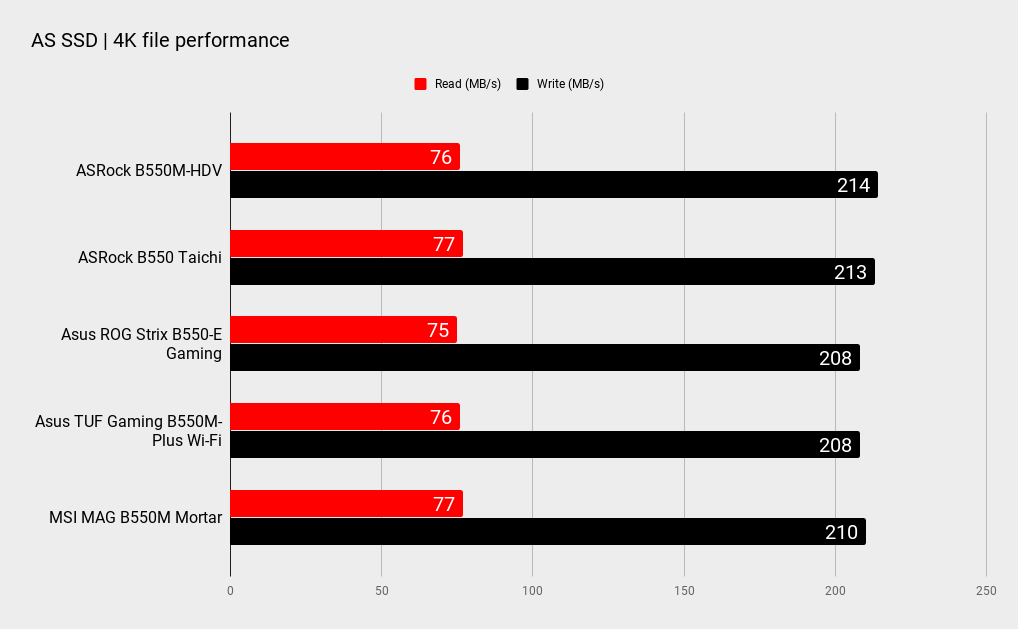

The most immediate and obvious consequence involves storage. You still get Gen 4 links directly into the CPU with the B550 chipset. There are 16 lanes available for graphics and another four for storage, enabling support for a quad-lane PCIe Gen 4 M.2 SSD. But, where the X570 adds support for a second Gen 4 M.2 drive attached to the PCH chip, the B550’s secondary M.2 socket is capped at PCIe Gen 3 speeds.

The slower PCH link has implications for other bandwidth-sensitive features, including USB connectivity. But the impact isn’t all that onerous. It still supports up to two USB 3.1 Gen 2 ports, something that eluded the B450. The B550 is a new platform, of course, so includes support for both AMD’s latest Ryzen 3000 CPUs and upcoming processors based on the Zen 3 architecture, which should appear later this year under the Ryzen 4000 brand. There’s decent future proofing, then.

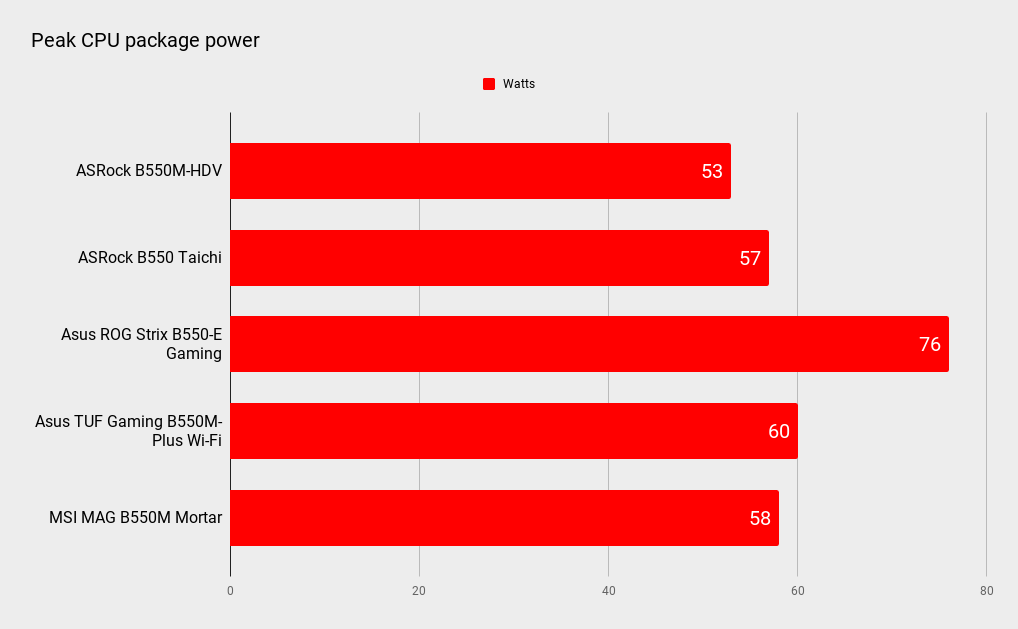

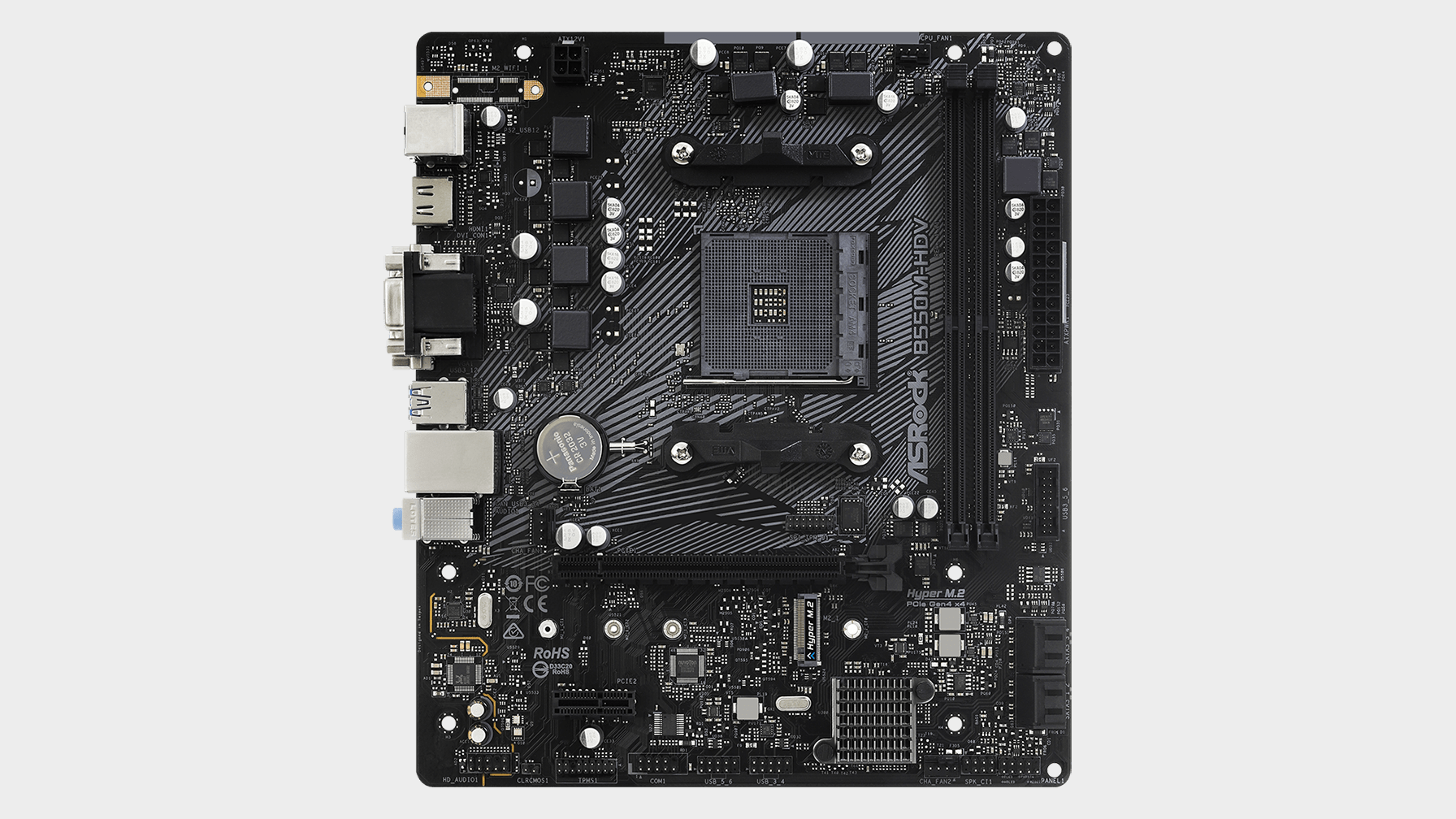

If that’s the general theory behind the B550, how does the specific implementation of the Asrock B550M-HDV stack up? No mistake, it looks as cheap as it is at first glance. You only get two memory DIMM slots, for instance. There’s just a single four-pin supplementary CPU power socket, too, which doesn’t bode well for overclocking. Nor does the minimal cooling. The VRMs are bare, the power delivery is merely four phase and just two fan headers are available.

Elsewhere, there’s a single USB 3.2 Gen 1 header, a couple of USB 2.0 headers, just four SATA ports, and a PCIe 3.0 x1 slot. On the back panel there are four USB-A 3.2 Gen 1 ports, a couple of USB-A 2.0 sockets, LAN, PS2, HDMI, VGA and DVI. What there isn’t? USB-C or DisplayPort.

Gaming performance

Hardware performance

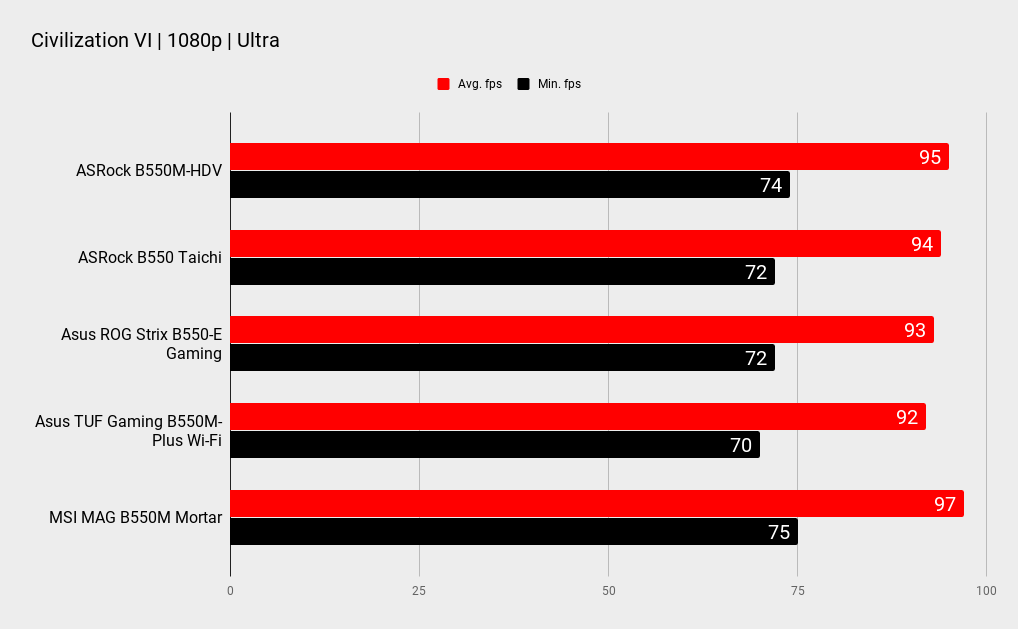

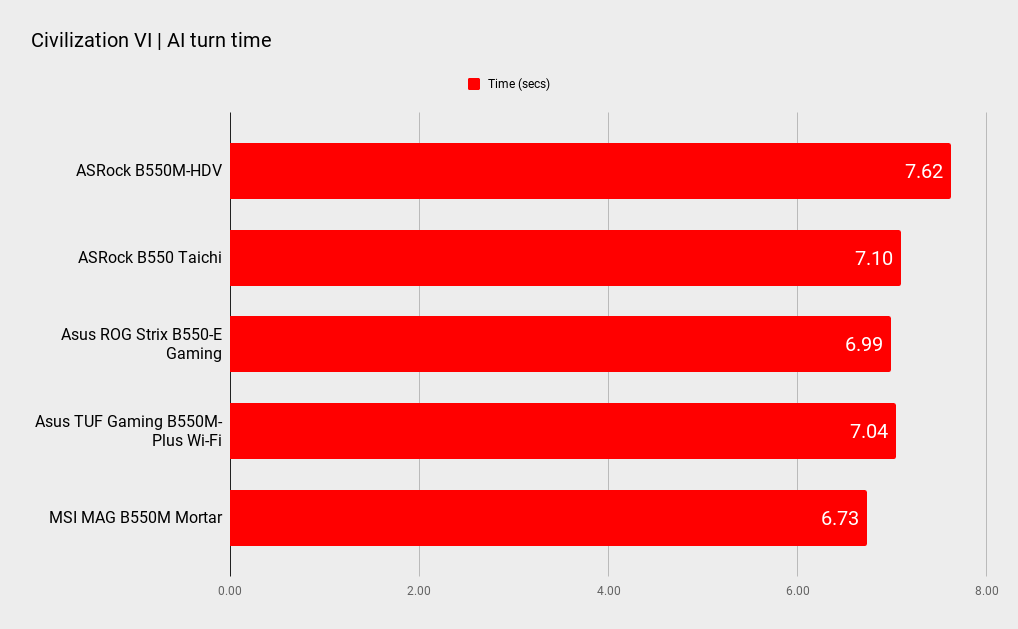

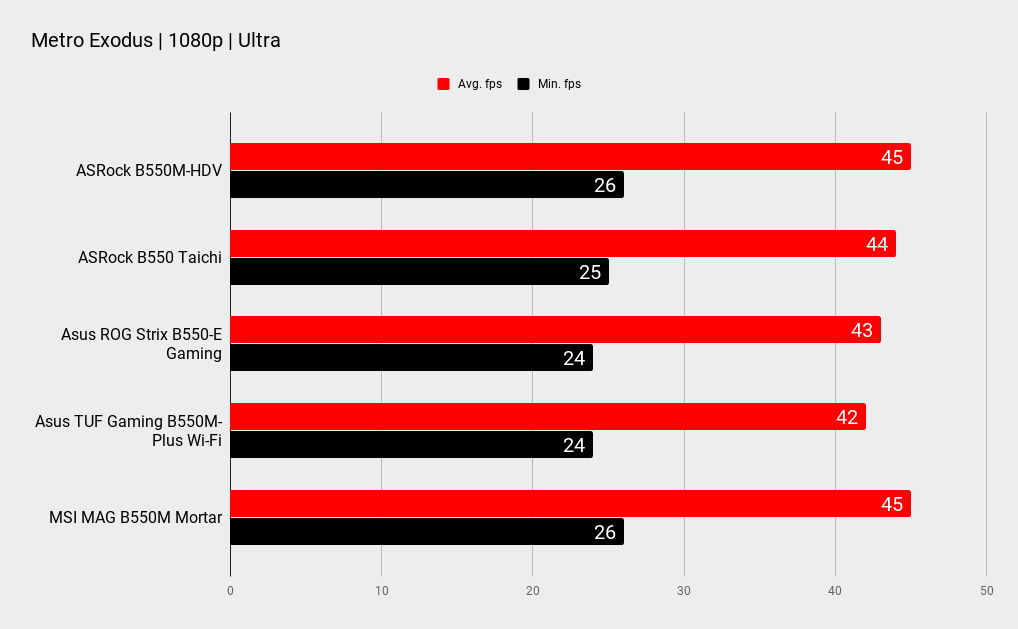

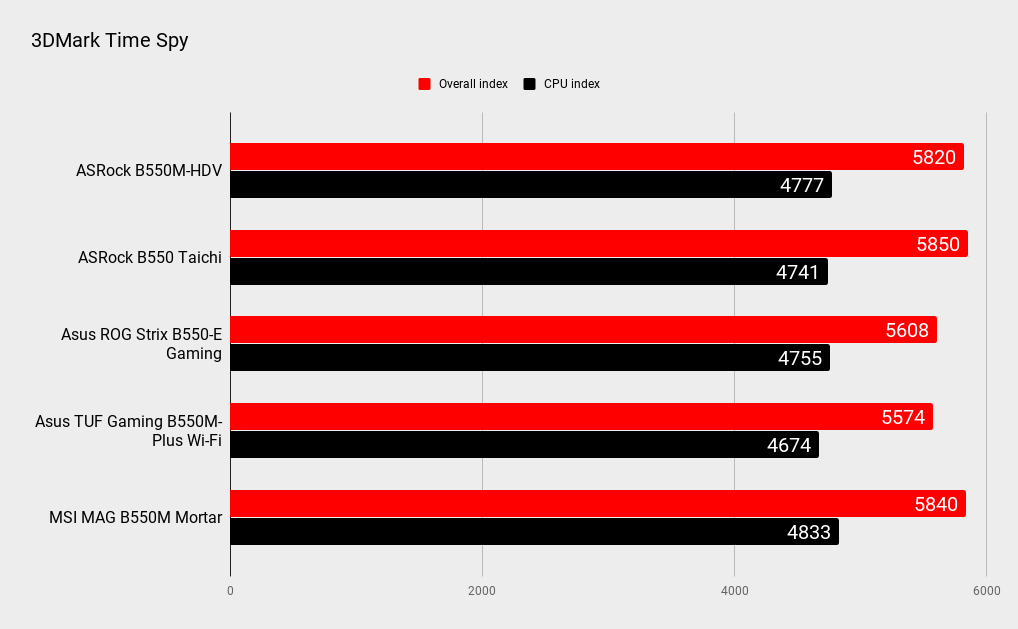

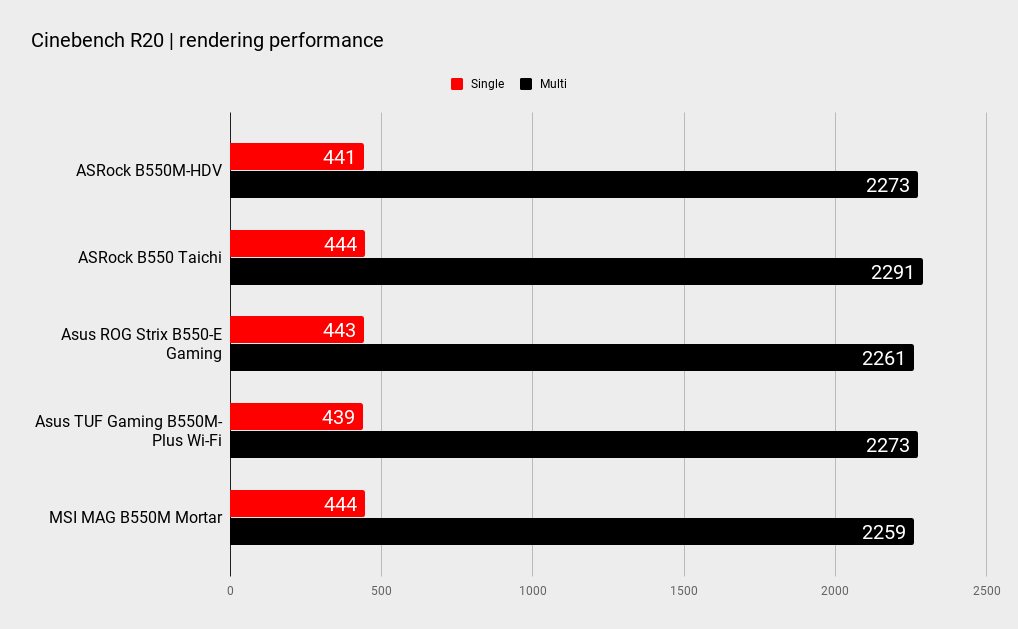

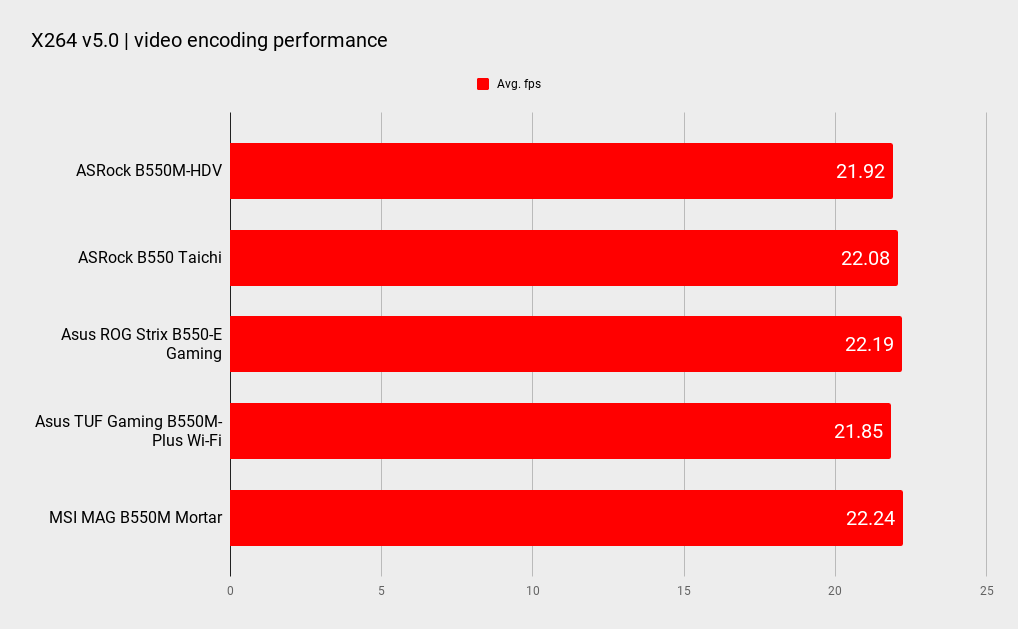

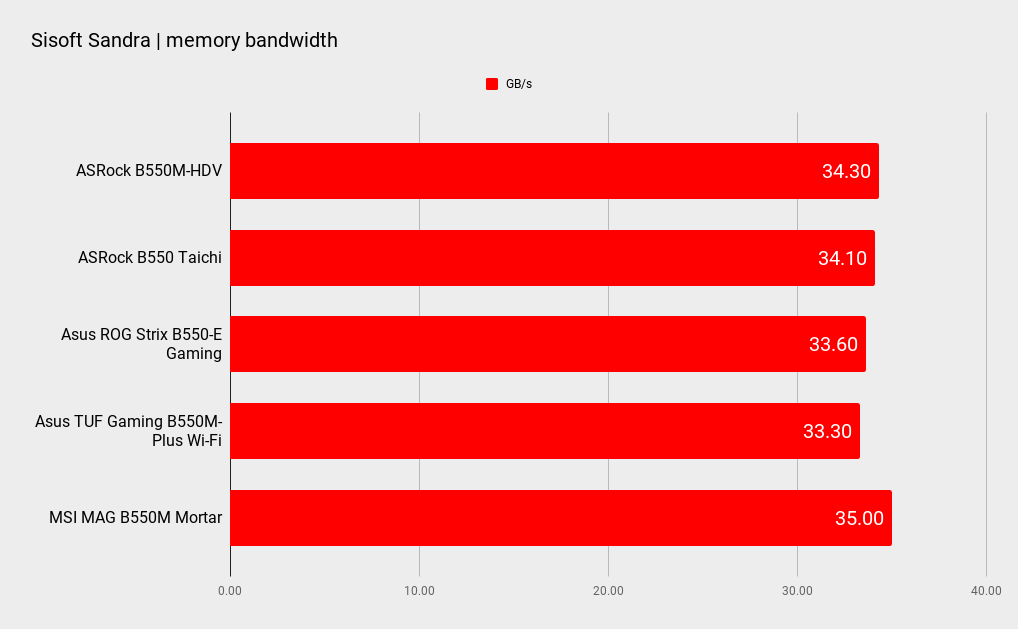

Of course, all of that is to ignore arguably the two most important features beyond the AM4 CPU socket, namely the x16 PCIe 4.0 graphics slot and the quad-lane PCIe 4.0 M.2 port. In other words, the really critical stuff for core PC performance is present, in theory. And so it proves in practice. The Asrock B550M-HDV puts in a more than creditable performance against far more expensive boards in pretty much all our stock-clocked benchmarks.

CPU - AMD Ryzen 3 3100

Memory - 16GB HyperX DDR4-3000

GPU - MSI GTX 1070 GamingX

Storage - 1TB Addlink S90

PSU - Phantec 1000W

That includes comparing favourably with Asrock’s own B550 Taichi board, which costs around four times as much. That includes CPU performance, storage, gaming, the lot. Actually, this budget board is faster than the megabucks Taichi in some benchmarks, albeit all the results are close enough to be within the margins of error and run-to-run variability. Put simply, you’d never feel the difference when it comes to the subjective computing experience when it comes to this board versus pricier options.

At least, that’s the case at standard clockspeeds. What about overclocking? Like the Asrock Taichi, the B550M-HDV doesn’t allow you to tweak the multiplier setting and allow the board to auto-select CPU voltage. So, novices will need to take care. But with the CPU running at 1.3v, this board achieves exactly the same all-core 4.2GHz as nearly all the B550s we’ve tested with our AMD Ryzen 3100 quad-core test chip.

The immediate conclusion might therefore be why pay more? The answer is that the Ryzen 3100 is not a terribly demanding chip. Odds are, you’d knock up against the limitation of that cheap four-phase power design and minimal cooling when overclocking CPUs with eight-plus cores. Of course, few existing Ryzen CPUs actually overclock well. So, that potential limitation doesn’t count for much. It’s possible that future AMD CPUs based on the Zen 3 architecture could provide more headroom. But that speculative and, in any case, at this price point you’re never going to get the last word in overclocking prowess.

Overall, then, our main reservation involves features. It would be quite nice to have at least one USB-C socket, here in 2020, plus a second M.2 slot. Either, but not both, of those are things you could add with a PCIe x1 board, though the M.2 slot would be limited to lowly x1 PCIe 3.0 speeds. And it's extra money. If those omissions matter to you, it probably makes sense to shop around and find a board that offers them as standard.

Asrock's new motherboard is a better fit with the B550 chipset's value-orientated positioning. Performance is on par with much more expensive boards, but connectivity and expansion is limited.

Jeremy has been writing about technology and PCs since the 90nm Netburst era (Google it!) and enjoys nothing more than a serious dissertation on the finer points of monitor input lag and overshoot followed by a forensic examination of advanced lithography. Or maybe he just likes machines that go “ping!” He also has a thing for tennis and cars.