Hands-on with Videoball: a local multiplayer electronic sport for the living room

It's all in the reflexes

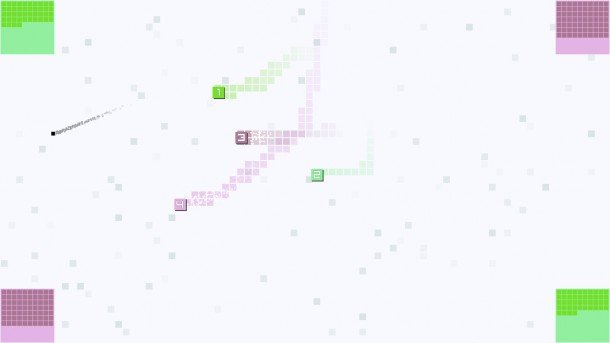

After a couple minutes I knew how to play Videoball, and I also knew that its simplicity leads to a deep competitive game ruled by timing and strategy, not complex mechanics. A single second's action or deliberate inaction can make a massive difference in Videoball. Every second you hold the action button, your little triangular player charges up a shot. A piddly level one shot will barely move the ball. A level two shot is like a solid kick. A level three shot is a slam that can knock a ball across the entire field. Hold the button for one more second after the level three shot, though, and your pulsing slam charge morphs into a defensive block—you can't hold onto the button and keep a powerful charge built up indefinitely.

The one second that passes between charging a slam shot and letting it transform into a defensive block—that's the game. That one second is Videoball.

Every strategic option in the game plays on that tight timing. Do you want to fire a level 2 shoot to knock the ball away from your opponent? Or wait until they fire and try to reflect the shot with a shot of your own, redirecting the ball's momentum? Do you fire a level 3 charge without being in a good position, hoping to knock the ball into an enemy (contact with the ball stuns you briefly) or try to get into a scoring position before the charge turns into a block? Do you position yourself on the back half of the field to play defensively and spawn blocks in front of your goal, or do you stay on the enemy's half of the field?

"We see a lot of basketball strategy happening, where you have someone being center or forward," Rogers said. "I'm talking about three-on-three...[With two-on-two] you'll see players start to play horizontal lines, along the bottom and the top, trusting each other. You'll see players start playing zones."

I played two games of Videoball two-on-two. The first game, two of us were learning. My team won 10-9 in about six minutes. In the second game, we started to grasp the basics of Videoball strategy, and played with only one ball on the field instead of two. My team won that game by a wider margin. But it took 20 minutes.

"Usually the games are over in about three to five minutes," Rogers said. "We had a two ball game on Sunday go to 22 minutes. And that's with people who've played the game over 100 hours each. We've had one ball games go to an hour. You start to see people stop releasing level 3 shots from their own zone due to the danger of it being reflected."

Even in an unfinished state—Videoball still has art polish to add, a soundtrack to expand, varied arenas to include, online play code to implement—I think the game has taken on the form of any successful sport. It supplies a field, simple rules, and straightforward mechanics. Player skill and strategy fill in the rest, like they do in football or basketball.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Bringing competition into the living room

When we talked, Rogers casually mentioned that Videoball can support more than six players, though three-on-three was the limit in the build we played. I don't know whether the final build of the game will allow for four-plus person teams, but I hope so.

The idea of four-on-four Videoball excites me, but it also highlights a longtime PC gaming weakness: local multiplayer. Since the Nintendo 64, consoles have supported four players on a single system. That doesn't work on a keyboard. Instead, the PC focuses on online gaming, which is great—better, for real-time strategy and games like Counter-Strike—but playing online is an alternative to playing together on a couch, not a replacement.

These days, most PC gamers have at least one controller in the house. But four? Or eight? That's a $100-$200 investment, and until now there's been no reason to take that plunge. I think 2014 is the first year those extra controllers will be worth buying. Videoball is only one reason.

Hokra, part of the Sportsfriends bundle planned for release on Steam in the spring, is another. Like Videoball, it's an abstract sports game that takes a few seconds to learn and then opens up to endless player strategy. The one-on-one tension of Nidhogg, which we loved , and the four-player chaos of Ouya darling Towerfall, coming March 11, are two more strong arguments for local competitive gaming.

SteamOS, Steam Machines, and in-home streaming finally provide an opportunity to bring the PC's thriving indie game scene into the living room. These games can take over parties and justify having four controllers around (one Xbox 360 wireless receiver, by the way, can sync with four controllers). There are still hurdles, like in-home streaming lag and the cost of buying a second computer for the living room. But for indie developers making small games like Hokra and Videoball, the PC represents an open platform without the challenges or costs of publishing on a console. And that means we're going to keep getting more of their games.

For the first time it's actually practical to play multiplayer PC games in the living room, and there's a growing list of competitive games offering a good reason to do so. When it comes out—hopefully in June—I think Videoball's going to be at the top of my list.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).