Why math is strangling videogame morality

Too many games still reduce their most important decisions to a number.

When I played Ultima IV as a kid, there was an element of mystery to it, by which I mean my friends and I had no clue what was going on. We took turns being in control and arguing over how best to live up to the eight virtues of honesty—compassion, justice, sacrifice, spirituality, valor, humility, and honor—necessary to adopt the mantle of the Avatar. That's a hell of a thing to ask a group of 12-year-olds.

When a vision told us it was compassionate to "Kill not the non-evil beasts of the land" we figured snakes aren't inherently evil, right? But if we ran away from snakes, would that count against our valor? The only way to check our progress in the eight virtues was to travel all the way back to Castle Britannia and speak to Hawkwind the Seer, so we were never sure in the moment whether we were doing the right thing. If someone asks you whether you're brave do you say "yes" to be honest, or "no" to be humble? It's a goddamn quandary.

We didn't manage to finish Ultima IV. Not many people did. Even during playtesting, only its designer Richard Garriott was able to get to the end, as he admitted in an interview in 1986. Replaying it again today I go straight to the FAQs. It's disappointing to learn that the secret behind those big questions we grappled with as kids is just a set of eight numbers going up or down. There are even people who have calculated how easy it is to rob Lord British of all his money, then go shopping and give a blind shopkeeper the right amount of cash to undo that crime. (Everyone who sells spell ingredients in Britannia is blind to make each shopping trip a test of honesty. Do you pay her the right amount or rip her off? They say justice is blind—in Ultima IV so is everyone who sells garlic.)

Even though the numbers underneath Ultima IV's decisions are simplistic, being faced with those big moral questions was novel, even revolutionary, at the time. What's disappointing is that in the 22 years since Ultima IV, the math governing most morality systems in games has gotten more complicated, but it's still math. And it's still there. When our behavior is tied to an equation we've been trained to understand over the past two decades of gaming, the exciting nuance that should lie at the heart of moral decisions tends to disappear.

Behavior by the numbers

The games with moral choices that followed soon after Ultima IV tended to make it immediately obvious when you were being rewarded for good deeds or punished for bad. Quest for Glory II kept its Paladin Points secret but had an Honor stat right there on your character sheet that went up when you did nice things, like being polite during tea. The Adventures of Robin Hood and I Have No Mouth And I Must Scream both explored morality, but rewarded you for 'good' behavior with a meter going up and punished you if it ever went down.

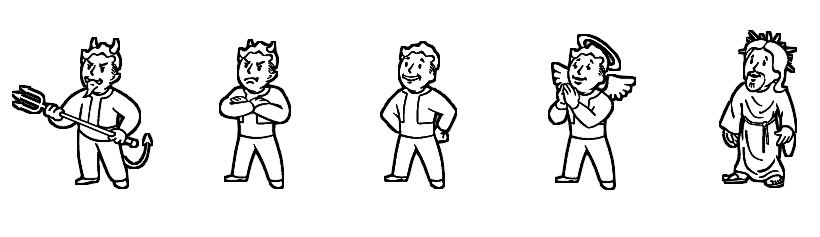

The next wave of games with morality were less focused on being nice. They made allowances for naughtiness as a valid playstyle (though admittedly Quest for Glory II did the same if you played the Thief class). Games like Jedi Knight, Fallout, and Baldur's Gate tracked your deeds and assigned a reputation, having characters react differently or showing different versions of cutscenes based on whether you seemed like the kind of player who would like to arbitrarily murder NPCs.

Knights of the Old Republic made an important step forward by melding the two, with a plot that made a dark-side playthrough possible as well as a meter that went up or down depending on whether you earned light side points or dark. Its sequel kept those meters, but is one of the few examples of a game from the past decade taking advantage of them. KotOR 2 offers probably the most nuanced deconstruction of the Force across all of Star Wars media, questioning the meaning of light and dark, and subverting the distinction between good and bad whenever possible. But a number, your 'alignment points,' still determined what Force powers you'd ultimately be able to use.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

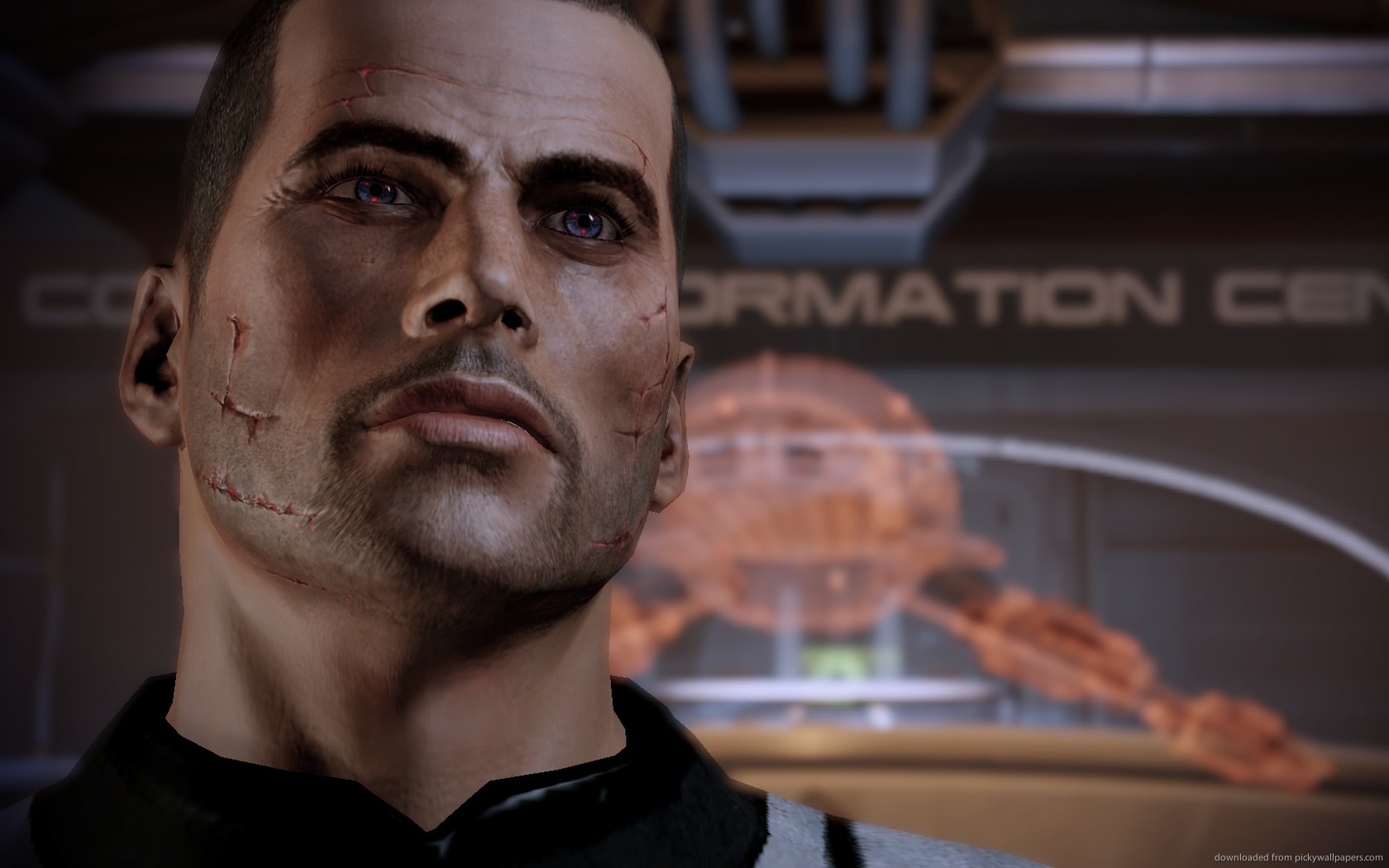

Mass Effect tried to be more nuanced by replacing good and evil with Paragon and Renegade, which many players read as new names for the light side and the dark. But in Mass Effect you're really always good, it's just that sometimes you're lawful and sometimes chaotic. Paragon means "by the book" and Renegade means "fuck the rules, I'm right." Admittedly in the first game Renegade was also a synonym for "quite xenophobic" which was odd, but they tried.

Your karma score in New Vegas keeps going up because you accidentally made the world a better place.

Once again there was a simple number underneath, and that number determined which conversation options were available to you. If the number wasn't right sometimes an option would be grayed-out, which encourages gaming the system by going all-out on one or the other paths, rather than judging each situation on its own merits and actually thinking through those dilemmas. Playing the middle ground may have felt more genuine, but the equation discouraged it.

It's true that we like to see numbers going up, whether it's a high score or character level, but reducing morality to another a number simplifies things a little too much. In Fallout: New Vegas, you earn karma by killing feral ghouls or Powder Gangers, because those are some bad dudes. That means if you're playing a villain and you get jumped by other bad guys, self-defence makes you a hero again. It's hard to keep a low karma score in New Vegas. It keeps going up when you're not looking because you accidentally made the world a better place.

Mega Man Legends 2 (which actually came to PC, though not in the West) is an extreme example of morality reduced to brute math. There's a black market where you can buy sweet gear, but only nasty people can shop there. Mega Man has to go around arbitrarily kicking pigs—that's literal, it's not a joke—to become more evil, as signified by his blue armor turning dark. Once he's punted enough pigs he goes shopping in the black market, then afterward makes a donation to the church to get back on the nice list and turn blue again.

In the late Middle Ages the Catholic Church sold indulgences, which lessened the amount of punishment you'd receive in the afterlife for your sins. If you wanted to be allowed to break the stricture against using butter during Lent you could pay for that, and Rouen Cathedral in France earned so much money from the practice they used it to pay for a whole new edifice that is still called Butter Tower to this day.

That's the level morality systems are at in most videogames.

Morality tomorrow

Most games, but not all of them. The Witcher 3, for instance, doesn't have a morality meter. As monster hunter Geralt of Rivia you're given options to turn down quest rewards or haggle the payment upwards, but there's no reputation score rising or falling in response. If you want Geralt's rough exterior to conceal a heart of gold you play him that way. If you want him to be rough to the core that's fine too. And there will be consequences for your choices.

Early in the game you meet Lena, a woman who has been seriously injured by the griffin you're hunting. Left in the care of the local herbalist, she'll probably die. You've got a potion that could help her, but it's made for witchers like you rather than normal humans and it might have serious side effects. It may even kill her, and she'll die in even greater pain.

Do you interfere or let things take their course? You're not related to this woman, you're not her primary caregiver. Maybe the potion will save her, but do you have the right to muscle in and jam poison down her throat because of a maybe? I did, and it saved her life. But then, after another 50 hours of Witchering about, I met her boyfriend.

He was stationed in an army camp on the edge of the map, which I only stumbled into because there was a noticeboard there and I wanted to find some more sidequests. He told me Lena had never fully recovered, that she couldn't speak and didn't seem to recognize anyone she knew. She'd been permanently brain damaged by my potion, and he didn't know whether to thank me for saving her or curse me for reducing her to this. Geralt's response was, "Trust me—choice I had to make was harder."

Not every sidequest in The Witcher 3 is as effective as that, and plenty of them boil down to following your witcher senses to the next marker then fighting a monster, but that just makes it unexpected when some of them throw their consequences back in your face—an element of mystery more effective than having to visit a seer in Ultima IV. I made a choice and that choice had an effect. No number went up or down, but a person confronted me and questioned what I'd done.

Bioware has said that Mass Effect: Andromeda won't have Renegade or Paragon points. Hopefully instead we get more repercussions directly resulting from actions—something the series has already dabbled in, to give it credit. In the first Mass Effect I met the Rachni Queen, last broodmother of her kind, whose children had been taken from her, driven mad and turned deadly. Though sparing her meant it could happen again, it also netted me some sweet Paragon Points.

When she turned up again in Mass Effect 3, once again shackled and her children forced to kill, it was a far more effective follow-through than the change in my score. I took a risk and had to deal with the fallout.

Every now and then games nail that sense of a chain reaction, of inevitable but unforeseen things happening because of how you chose to deal with mad Ekkill in The Banner Saga or who you let through the checkpoint in Papers, Please. In Telltale's games you know immediately that a choice will have an aftermath, because the pop-up tells you that someone is going to "remember that." That's how I want to feel about every choice without being told, or seeing a meter go up—that when I least expect it, the waves I set in motion will roll back to shore and wash up something dreadful at my feet.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.