The pressure to constantly update games is pushing the industry to a breaking point

Live service games have trained players to expect a constant stream of new content, and only constant work can deliver it.

In 2004, the partner of an EA employee with the pseudonym EA Spouse wrote about the conditions her significant other was working under during a particularly brutal crunch period. He worked 9 am to 10 pm seven days a week, "with the occasional Saturday evening off for good behavior." No overtime pay or other compensation. No deadline for when this would end. He was not alone, and subsequently others spoke out about similar conditions. There were class-action lawsuits, which EA chose to settle for millions of dollars.

In the years since, the conversation about crunch in the games industry has spread beyond whisper networks and isolated exposés, becoming much more common. Developers have been emboldened to speak out about conditions at other employers, from Rockstar to Telltale to NetherRealm. But crunch remains a serious problem.

Another story has become intertwined with crunch: Developers aren't just being worked into the ground to hit a development milestone or a release date any more, because for many games that's just the starting line. Living games demand a constant stream of content, and only constant work can deliver it.

This is the crunch that never ends

Live games are so permanently in a state of development there's no breather just because the game's shipped.

Large videogame studios often work on a similar model to the film industry, with contract workers hired for the latest project and then let go at its completion. Employment agency TargetCW has said that 10 to 15% staff in the creative departments of game publishers are contractors, and that number goes up every year. A core of permanent staff stays on, and can start taking vacation days once a project's complete should they be lucky enough to earn them, but a significant number of contractors are overworked without benefits or paid time off. When they inevitably burn out the result is a constant churn as skilled workers leave the industry and are replaced by a younger generation, many of whom will burn out in the same way.

(It's worth noting that this is much less likely to happen in countries with strict labor laws protecting workers, but not every game developer can work in, say, Sweden.)

What's changed is that triple-A games can no longer be patched by a skeleton staff after their release. Nowadays players demand big updates, and games have trained them to expect those updates to be frequent. First there were season passes and limited-duration events, and now live games are so permanently in a state of development there's no breather just because the game's shipped.

As an extreme example there's Fortnite, which receives weekly patches and fortnightly updates. An investigation published by Polygon revealed the consequence of that—employees working 70-hour or even 100-hour weeks. "The biggest problem is that we're patching all the time," one employee said. If something goes wrong in one of the regular updates, like a weapon breaking, there's no option to take time fixing it. "It has to be fixed immediately," they said, "and all the while, we're still working on next week's patch. It's brutal."

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

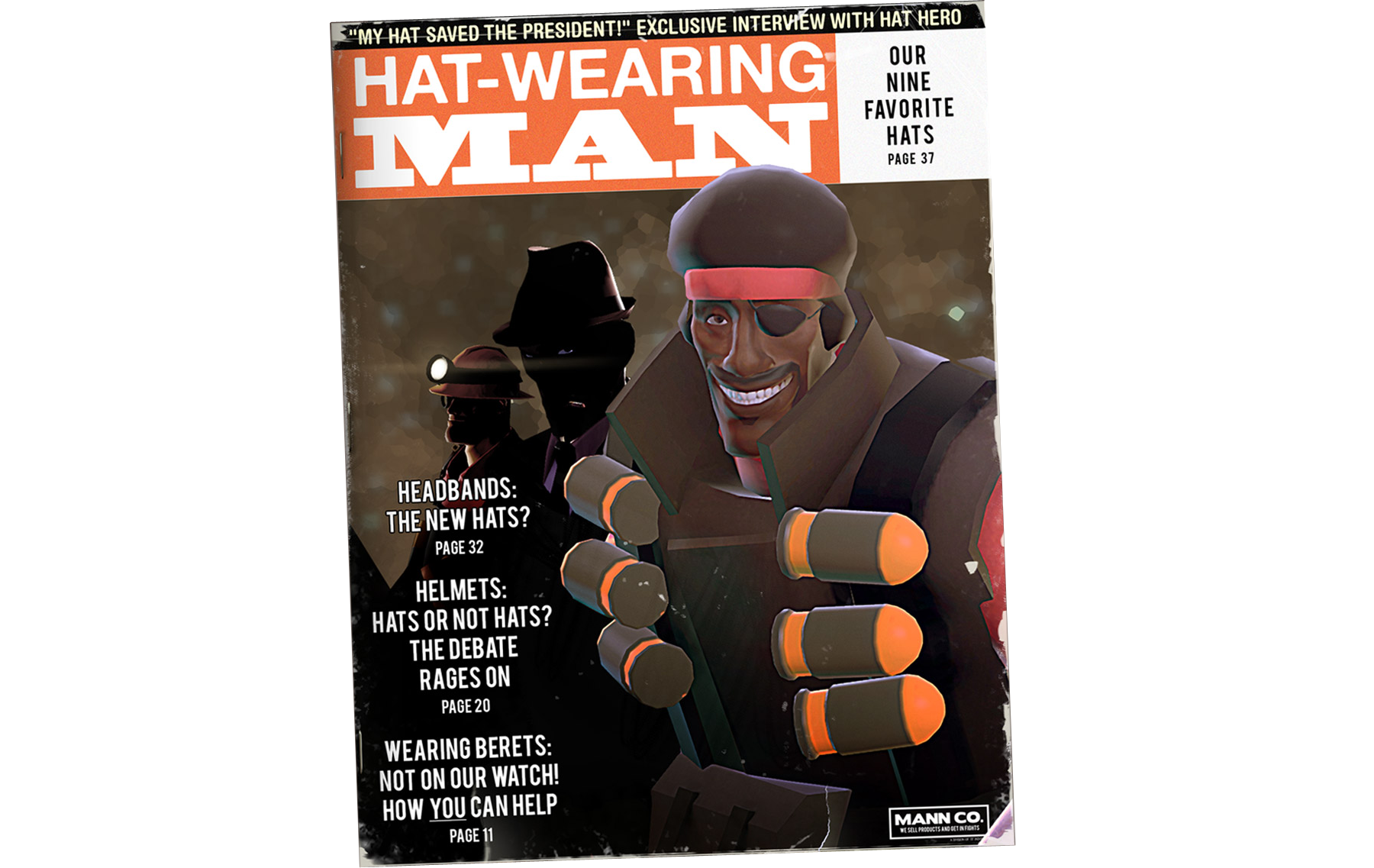

It hasn't always been like this. There was a time when Team Fortress 2 was the only game in your library that was always in the queue for an update.

How we got here

Valve's online shooter has changed a lot since 2007, gaining new weapons, maps, cosmetics (yes, mostly hats), and going free-to-play. Team Fortress 2 was a prototype for how to keep a game alive with regular updates, and the lessons Valve learned from it were applied to Counter-Strike and Dota 2, which engaged in duelling updates with League of Legends. League of Legends, for years the biggest game in the world, helped establish the template of the live service game and the constant need for momentum. Riot released a new champion every other week for three years before slowing down.

Games like League and Fortnite don't just do the big, splashy updates. There's a treadmill of tweaks as well, of regular buffs and nerfs, and keeping up with all of them would be a full-time job.

Other multiplayer shooters and MOBAs have had to keep up, and the expectations of those free-to-play games have largely been carried over to the likes of Destiny 2.

For a counter-example, there's Apex Legends. A game in the same genre as Fortnite, one that couldn't be any more "game as a service" unless it had a Marvel movie tie-in event. And yet, creators Respawn responded to a remarkably successful launch by saying they weren't going to change their plans and were in fact happy to update it slowly.

"Our intention was to always be seasonal, so we're kind of staying with that," Respawn's CEO Vince Zampella was quoted as saying. "The thought was 'hey we kind of have something that’s blowing up here, do we want to start trying to drop more content?' But I think you look at quality of life for the team. We don't want to overwork the team, and drop the quality of the assets we’re putting out. We want to try and raise that.”

In 2019, Respawn released the Live Balance Update. As the patch notes made clear, this slower pace is considered a feature. It's not only a way to prevent the team from being overworked, but a way to make a better game: "The goal is to ship polished, closer to the mark updates than if we got things out rapidly and iterated in the live environment. [...] Our goal is to make less frequent, better tested, higher impact changes, so it minimizes the effects on your time spent mastering a particular mechanic, weapon, character, etc. You shouldn't have to read our patch notes every few days just to keep up with how characters and weapons now work."

Always be streaming

And what was the reaction to this sensible approach? Analyzing the reduction in its Twitch viewership so dozens of YouTube videos could declare a game only four months old was dying.

It's true that Apex Legends average of 200,000 concurrent viewers for its first couple of weeks dropped sharply. But when it launched some of the biggest and most influential streamers in the world were being paid to play it. Once those streamers went back to Fortnite (and its $100M World Cup) or onto another craze, which for many was GTA Online roleplay, of course the viewer count went down. Yet when a game doesn't do its damnedest to maintain momentum by any means possible, it's punished.

A knock-on effect of the games industry's focus on maintaining momentum, and encouraging players to keep up with them, is that even streamers are effectively crunching. Twitch streamers live by their numbers, and when they step away from the computer those numbers drop immediately.

As streamer ShannaNina told Wired, "If you sit there for four hours and work your way up to 200 viewers, when you take a 15-minute break it drops down to 130 or 140 viewers," and that's a small streamer taking a bathroom break. At the opposite end of the scale, when Ninja takes two days off, he loses 40,000 subscribers.

It encourages a mantra of "always be streaming" exemplified by CohhCarnage, who once streamed for 2,000 days straight. Games are constantly changing and so the audience wants their favorite streamers to be there documenting them daily—and if the streamers are always streaming, then there better always be new content for them to stream. The unhealthy conditions developers work under are mirrored by the professional players streaming the same games.

"It took a mental toll on me for sure," wrote Lirik, one of Twitch's biggest stars, in 2018. "Made me actually wonder and question my choices and what the fuck I was doing and made me extremely self-conscious. It also put me into this really shitty routine of streaming, eating bad, reading stupid shit, being in a bad mood, and regurgitating almost every day." Twitch has even addressed burnout and disconnecting in its own guidance for streamers.

The roadmap is not the territory

A sign of these momentum-obsessed times is that every game has to come with a roadmap. Launchers have roadmaps now, with Epic outlining six months worth of planned features for theirs. The months ahead have already been planned out for Fallout 76, Hitman 3, and Star Citizen.

Even Forager—an indie crafting game that's obviously a labor of love and mostly the work of a solo developer—had one. Roadmaps are a promise that a game and its community won't be abandoned, that it will be a living thing.

Heaven help the developer that abandons or alters the roadmap. When BioWare announced features that were part of Anthem's roadmap would have to be delayed indefinitely so they could focus instead on the basics of "bug fixes, stability and game flow" the response was overwhelmingly hostile.

If a game like Apex Legends isn't immediately the biggest thing in its genre, naturally shrinking player counts are heralded as a sign of doom.

While Anthem was not well-loved by reviewers when it launched (our own Steven Messner criticised its "disjointed story, boring loot, repetitive missions, and shallow endgame"), BioWare fans were vocal in its defense. That changed fast. A look at the Anthem subreddit after launch painted a much bleaker picture, with posts about how "the trust is gone" and that fans' goodwill was "sneakily garnered from the community before launch with shady business tactics."

The obsession with momentum hasn't just changed how games are made; it's changed how we perceive them, how we talk about them, and how they're designed.

It's changed how we perceive them because accounts with thousands of hours of playtime are investments, and a disappointing update (or no updates at all) can seem like a hit to the value of that investment. We've put in the hours and we feel we deserve to be rewarded for that—when the latest patch doesn't fix the bug we saw or change the ability we keep getting killed by, it makes it plain how one-sided the relationship is. It's an absurd way to think but that's what sunk costs do to us.

It's changed how we talk about games because conversations around new games are crowded by what's being renewed, and there's only so much attention to go around. If a game like Apex Legends isn't immediately the biggest thing in its genre, naturally shrinking player counts are heralded as a sign of doom.

On the design side the effect on multiplayer games is obvious—everything about games as a service and how manipulative they can seem comes down to their need to maintain momentum. Singleplayer games aren't immune. Some of the biggest, like each new Assassin's Creed, have a calculated drip-feed of progression to keep players coming back and talking about the game for months instead of weeks, only speeding up if you drop money on an XP booster.

Someone, somewhere has done the math, weighed that and the human cost against the bottom line, and put us where we are now.

None of this is new, but it is escalating. In 2013, EA released 13 big-budget games, not counting the likes of FIFA Manager 14 or Ultima Forever: Quest for the Avatar. Just including the tentpole releases there were six sports games in their respective annual series, a new Battlefield, Crysis, Dead Space, Army of Two, and Need for Speed, as well as a SimCity reboot and Fuse. In 2018, EA would only release seven games of comparable budgets—six annualized sports games and another new Battlefield. And yet its annual revenue grew from $3.797 billion in 2013 to $5.15 billion in 2018.

Tim Sweeney said this to Edge magazine: "The industry’s changing—this generation it seems like there are about a third of the number of triple-A titles in development across the industry as there was last time around—and each one seems to have about three times the budget of the previous generation." These games are too expensive to take risks with, and not squeezing every dollar of profit out of them is seen as a risk. You'd think the outcome of the class-action lawsuits following the EA Spouse revelations would change that, but presumably someone, somewhere has done the math, weighed that and the human cost against the bottom line, and put us where we are now.

Without a massive push for change from players and workers, this path isn't going to change. It's proven profitable. But there are organizations like Game Workers Unite that could make a difference, and just being aware of the human cost of making today's biggest games is a small step forward. It's become common to see people react to news of a game being delayed with variations on Shigeru Miyamoto's quote, "A delayed game is eventually good, but a rushed game is forever bad." When game updates come out slower than expected, or Twitch viewer counts drop, that same understanding needs to apply.

It's OK for things to take their time. Sisyphus isn't going to get that boulder to the top of the hill any faster by updating his roadmap and putting in 100-hour weeks.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.