The making of Fort Frolic, Bioshock's most twisted and memorable level

Building Sander Cohen's demented nightmare.

To celebrate BioShock's release ten years ago, here's our 2016 making of what was arguably its best level, Fort Frolic.

"Being the best at what you do can really take it out of you,” crackles a recorded voice through a speaker system. “So it’s time to unwind! Gamble, shop, take in a show, or meet a new friend, all at Fort Frolic, where the best and brightest celebrate success.”

Fort Frolic is the seventh level in the original BioShock. Protagonist Jack is trapped in a neon-lit adult playground by the demented Sander Cohen, who forces him to help in the creation of a macabre work of art. The design of the level was led by Jordan Thomas, whose previous work included Thief: Deadly Shadows’ infamous Shalebridge Cradle, and who would later go on to direct BioShock 2.

“I came onto the BioShock team about a year from ship,” says Thomas. “The level was in a fairly skeletal state. And since it was relatively tangential to the core plot, director/writer Ken Levine and designer Paul Hellquist put me in charge of it, knowing I had a history for making creepy stuff.”

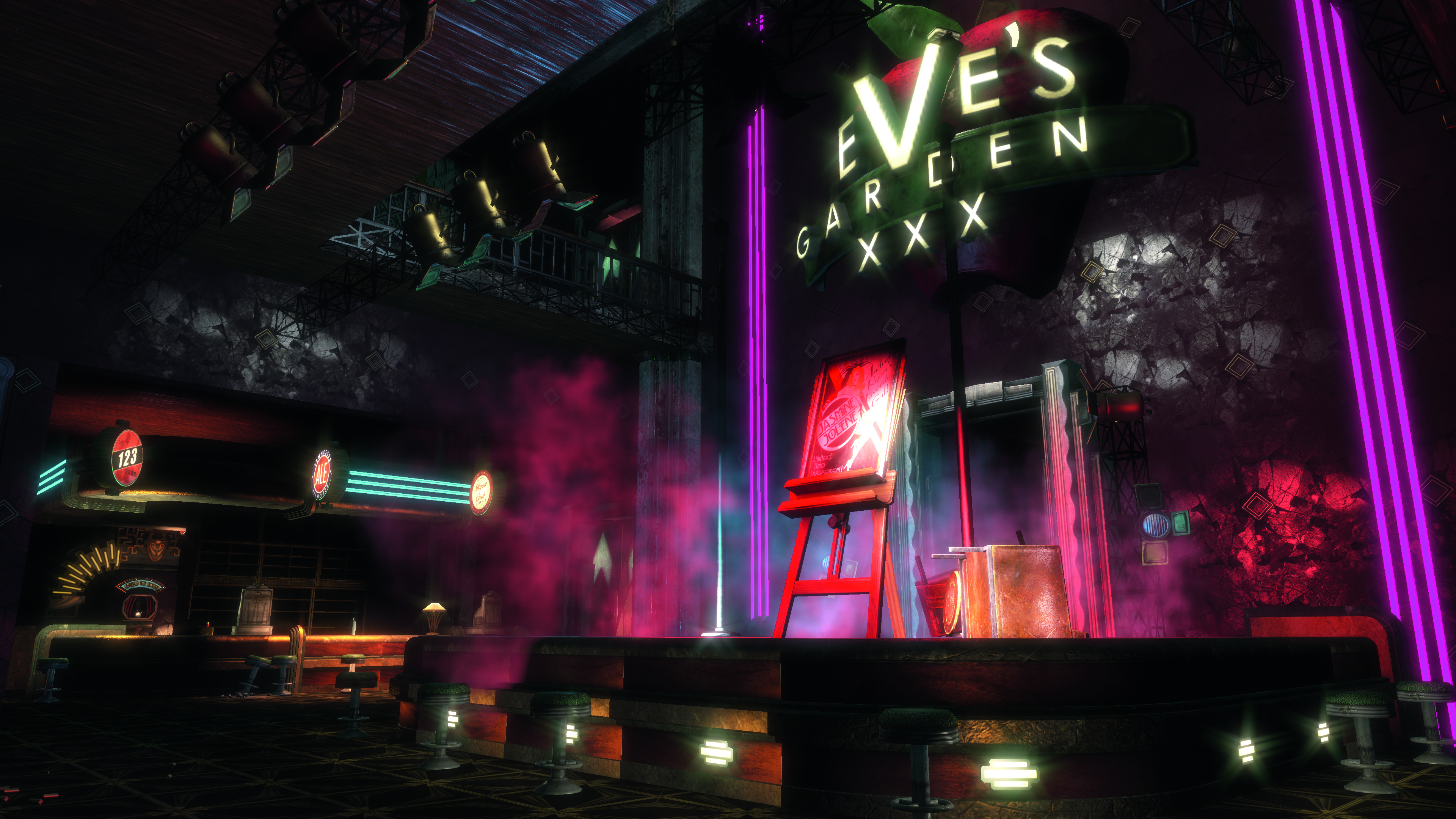

Fort Frolic was built as a place for the residents of Rapture to relax, featuring cocktail bars, department stores, casinos, art galleries, strip clubs, and a theatre, the Fleet Hall. Cohen, Rapture’s most celebrated polymath, made it his home in the city, and as he slipped deeper into madness, the district became a sinister monument to his cruelty and egomania. “I’ve seen all kinds of cut-throats, freaks, and hard cases in my life,” says Atlas. “But Cohen? He’s a real lunatic. A dyed-in-the-wool psychopath.”

I ask Thomas what he wanted Fort Frolic to reveal about Rapture. “The fundamental sadness of these Great Men who want, above all, to boil people down to their ideals and aesthetics—to replace them with abstracts,” he says. “There’s a line I wrote for Andrew Ryan in BioShock 2 to sum that concept up, where he says to himself: at last, I am alone with my city. A core contradiction in terms, but guys like Ryan and Cohen push people away when they don’t match the mental model. Literally, in Cohen’s case.”

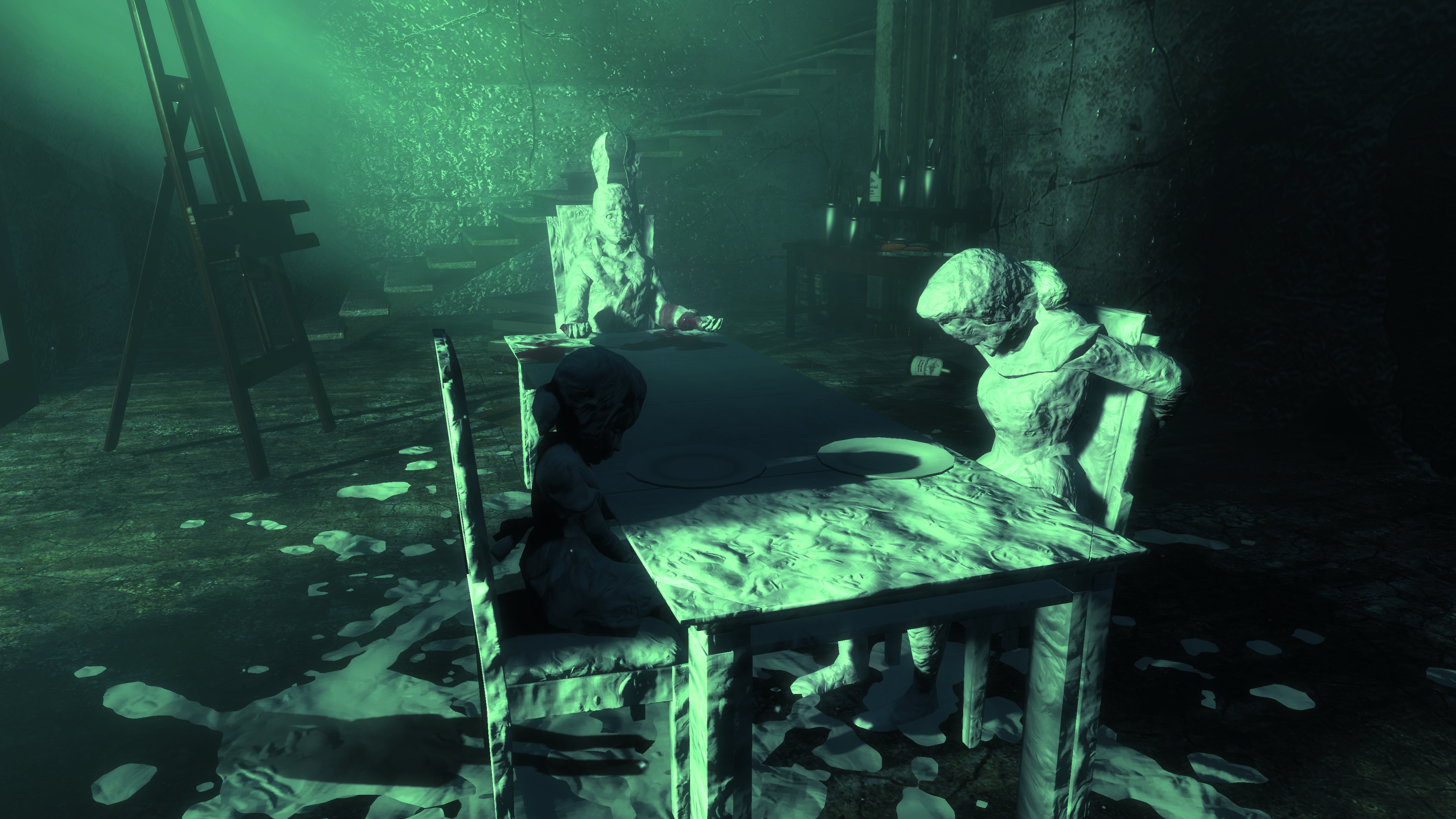

Cohen closed Fort Frolic to the public following the 1959 civil war that ultimately ruined Rapture, but promised the people “one final frolic”. Not everyone made it out before the closure, however, and many of these unfortunate souls ended up as bizarre works of art themselves. Almost everywhere you go in Fort Frolic you find bodies encased in plaster, posed by Cohen. You think they’re just sculptures at first, but get closer and you can see blood leaking from the cracks, revealing the grim truth.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“We also tried to hint at, without getting pornographic, Cohen’s conflict with his own sexuality. But people read that much dirtier than we intended. Go figure!”

Jordan Thomas

“I begged the art team to help with the plaster statue scenes, which were kind of my baby,” says Thomas. “I really wanted Cohen to use the living and the dead interchangeably in his ‘art’ so that when you finally made the decision to kill or spare him, you could make some kind of counter-statement, up to and including taking a final death portrait of the man himself.” Thomas also worked closely with the AI team, including John Abercrombie, to make the plaster statues move when you weren’t looking.

Cohen’s obsession with the statues had roots in cinema, particularly Norman Bates’ mother in Psycho and Rupert Pupkin’s imaginary basement audience in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy. “It was psychodrama externalised,” says Thomas. “We also tried to hint at, without getting pornographic, Cohen’s conflict with his own sexuality. But people read that much dirtier than we intended. Go figure!”

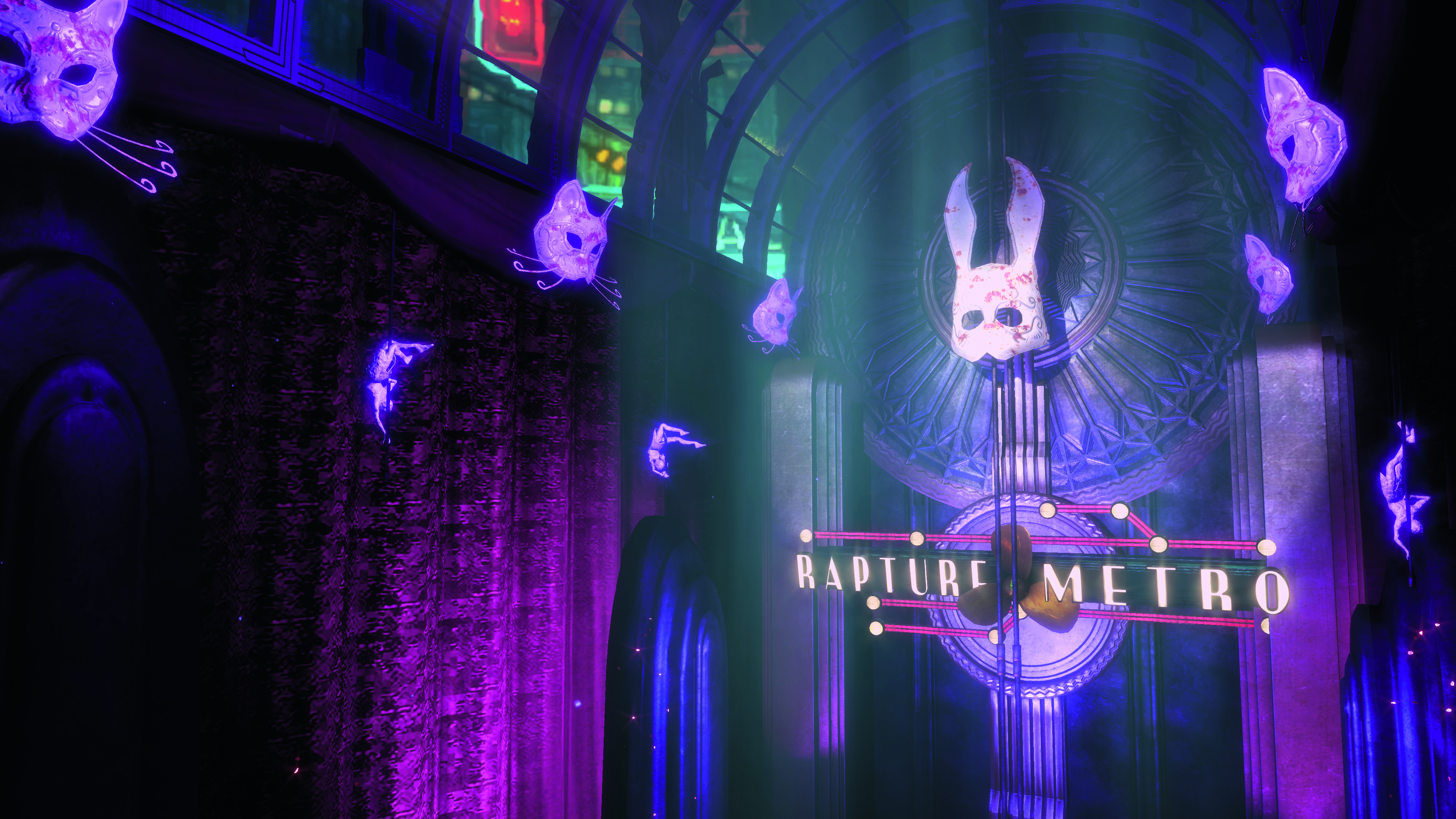

Cohen’s introduction is one of BioShock’s most memorable moments. Jack approaches the bathysphere in Fort Frolic’s metro station to travel to the next part of the city, but the gate slams shut. Then composer Garry Schyman’s beautiful, haunting “Dancers on a String” plays as figures encased in plaster descend from the ceiling, posed like ballerinas and spinning slowly to the music.

“I pitched a sort of Cirque du Soleil meets Animal Farm thing,” says Thomas, “with rope dancers and purple lights that responded in time to everything Cohen said—which they do throughout the level. Since we had to hold actually meeting him back until the end, the idea was to infuse the space with his presence, everywhere you looked.”

The bunny masks worn by the splicers in BioShock have become a big part of the game’s visual identity, and they’re also a strong presence in Fort Frolic. “Thank God Scott Sinclair loved animal masks!” says Thomas of BioShock’s art director. “The bunny theme really caught on with him, then Ken wrote it in. It helped us fight back against people thinking Cohen was just The Joker.”

Fort Frolic isn't Bioshock's only great moment. Here's a collection of our favourite bits from throughout the series.

The deranged artist’s voice booms from some unknown source as the bathysphere sinks into the water. “Atlas, Ryan, Atlas, Ryan,” he says wearily. “Time was you could get something decent on the radio. The artist has a duty to seduce the ear and delight the spirit.” Then he perks up suddenly. “So say goodbye to those two blowhards, and hello to an evening with Sander Cohen!”

At this point, Cohen tests your mettle by sending a group of splicers after you. After you defeat them he grants you entry to the atrium—a visually stunning central hub for the Fort Frolic level. It’s dark when you first enter, then Schyman’s score swells as a collection of gorgeous, colourful neon lights advertising Frolic’s stores and bars blink into life. When Cohen speaks the lights in the room turn purple, and if you anger him—attacking his artwork, for example—they turn red to mirror his rage. This is a subtle way of telling you that Cohen is intrinsically linked to this place.

“Honestly that was me stealing from myself, as far back as the Cradle,” says Thomas. “I love the moment when a semi-abandoned space comes to life, with power restored. It asserts, wordlessly, that it is a character unto itself. That’s something of a cliche now, but as of the first BioShock that idea still felt new to me.” Scott Sinclair and his art team were responsible for the bold, colourful look of the atrium, and Thomas adds that took him a while to get used to it. “I was raised in Seattle and we draw back from bright colour and hiss like flabby draculas.”

However, despite this vivid use of colour, there’s still plenty of darkness elsewhere in Fort Frolic. BioShock is, after all, a horror game. A lot of its creepiest moments happen in the basement areas, including the surreal image of a plaster sculpture sitting on a chair, facing a corner, lit by a flashing light as Patti Page’s recording of “(How Much Is) That Doggie in the Window?” plays eerily. It’s clear Thomas put his experience with the Cradle to good use when creating these moments.

Rapture is a city filled with tragedy, but one story in particular is especially moving—that of Jasmine Jolene. In her early days she was a chorus girl in one of Cohen’s Broadway musicals, before catching the eye of Andrew Ryan. He invited her to Rapture where she became a dancer at Eve’s Garden, a club in Fort Frolic. We see posters all over the level describing her as “Andrew Ryan’s favourite gal!”—a detail that becomes tinged with dark irony as we venture deeper into Fort Frolic and learn more about her.

There are bloody bodies all over Rapture, of course, but the added context and relevance to your character makes this one pack an extra emotional punch.

Through her story a major plot point is revealed that gives her extra significance—particularly to Jack. And there’s a haunting moment when you enter a room in the back of Eve’s Garden and find her brutalised body next to a blood-spattered poster of her in her prime. There are bloody bodies all over Rapture, of course, but the added context and relevance to your character makes this one pack an extra emotional punch. “My heart breaks a bit for Jasmine,” says Thomas. “She was an attempt to make just another dead body posed in the environment have multiple layers of significance that hit you harder and harder the deeper you go.”

Jack’s journey through Fort Frolic involves him visiting the Southern Mall, a shopping district littered with further examples of Cohen’s “human art”, a cocktail bar where the well-to-do would drink the night away, and a cigar shop. Later he moves through Poseidon Plaza and finds Sir Prize, a casino filled with one-armed bandits, and learns the horrible truth about Jasmine Jolene through ghostly flashbacks. There are bigger levels in BioShock, but Frolic makes up for its smaller scale with an incredible attention to detail and rich environmental storytelling.

When the player, as Jack, finishes helping Cohen create his “masterpiece”—a demented sculpture built around pictures of former disciples he forces you to kill and photograph—the man himself makes a grand entrance in the atrium. Fireworks explode, the recording of a cheering audience plays (another nod to The King of Comedy), and he marvels at his grim quadtych. “It’s beautiful!” he coos. “You’ll find your path to Ryan is now clear.”

Usually when you meet a major character in BioShock they’re safely hidden behind a wall or out of reach, so it’s a surprise when you see Cohen walking around openly. This lets the player know that, yes, you can kill him if you want to. But refusing to attack him unlocks an otherwise inaccessible “Power to the People” upgrade station later in the game, in Olympus Heights, so it’s worth sparing his life. The option is there, at least.

“This scene was a nightmare of scripting and effects work, and trying to make the player realise they had a choice. A fight was not forced, which was an attempt to seduce you into at least questioning whether, in his state of mind, Cohen deserves to die.” When it was finally working with minimal bugs, Thomas stood up and shouted “It’s done!” to an empty office at 3am. “I realised the irony of my lonely ‘masterpiece’ and went home.”

Compare the original games to their new remasters in this screenshot gallery.

Cohen is clearly mentally disturbed, and in many ways deciding whether to kill him or not is a more interesting moral choice than harvesting or sparing the Little Sisters. He’s a murderer and a villain, but there’s a tragedy to him as well. Through audio diaries we learn of his mental decline, and his burning resentment of Andrew Ryan. “I could have been the toast of Broadway, the talk of Hollywood,” he broods in one recording. “But instead I followed you to this soggy bucket. When you needed my starlight I illuminated you, but now I rot, waiting for an audience that never comes.”

It’s also suggested by Anna Culpepper, a musician who wrote songs criticising Rapture’s elite, that Cohen was being used, perhaps unwittingly, by Ryan as a propagandist. “Cohen’s not a musician,” she says in an audio log. “He’s Ryan’s stableboy. Ryan’s corrupt policies crap all over the place, and Cohen flutters around clearing it up. But instead of using a shovel, Cohen tidies with a catchy melody and a clever turn of phrase.”

Some ideas for Fort Frolic were left on the cutting room floor, including the planned inclusion of a ferris wheel—which later appeared in a console-only “challenge room” DLC. The developers also planned to make a zoo part of Fort Frolic, and some have expressed regret at having to cut it. No assets from the zoo have been discovered by data-miners, so it seems likely it never made it far past the concept phase. A shame, but Rapture itself is like one giant aquarium, so perhaps it didn’t need one. Early in BioShock 2’s development, players were supposed to pass through the flooded atrium of Fort Frolic on their way to Dionysus Park. “You’d be going through a sunken version of a level you’d remember from the first game,” designer Eric Sterner writes in the Deco Devolution BioShock 2 artbook. This idea was ultimately scrapped, but concept art shows the flooded ruins of the atrium.

“Fort Frolic taught me that narrative in games is all about theme, from the gross musculature down to the cellular level,” says Thomas, reflecting on the lessons he learned making the level. “The ideal case is that theme is a kind of space in which the player is invited to move to and fro, and the more pervasive, the less you have to worry that they won’t ‘get’ it.” The level is about art, narcissism, “and the struggle to include others in one’s private vision”. Everything the player does and sees, Thomas says, is a reflection of that. “The quest is literally to take photos of a scenario you can concoct, and players got very, uh, creative with their compositions. Suffice to say, I think Cohen found a lot of new disciples out there.”

If it’s set in space, Andy will probably write about it. He loves sci-fi, adventure games, taking screenshots, Twin Peaks, weird sims, Alien: Isolation, and anything with a good story.