The history of hit points

Before regenerating health, before Doomguy, before D&D RPGs...where did hit points come from?

The regeneration generation

MIDI Maze is an early example of another change in the way hit points worked, as it also had regenerating health. It wasn't the first, however. The action-RPG Hydlide, released on Japanese home computers like the PC-88 in 1984, gave players back hit points when they stood still. Where other games had food and first-aid kits that functioned as magically as the healing potions in fantasy RPGs, regenerating health—though no more realistic—at least took health items out of the game world. It made healing an abstraction like hit points are, rather than requiring players assume Johnny Medkit has wandered the world ahead of them scattering healing items like seeds.

It was Halo: Combat Evolved that popularized regenerating health, which is ironic because it didn't really have it. Halo's hero Master Chief wears an energy shield that regenerates after a short interval without taking damage, but once that's gone he has a traditional life bar that can only be refilled with medkits.

However, the recharging energy shield was what gave Halo its famous “30 seconds of fun that happened over and over and over and over again” as designer Jaime Griesemer put it, letting players pop out of cover to shoot aliens and then duck back to recharge and reload, and that's what had a lasting impact.

The idea was copied and modified by plenty of other games. Call Of Duty has become the flag-bearer for regenerating health, taking the blame for its propagation though it wasn't introduced until the second game in the series. Even in the mid-2000s as it was first becoming widespread, regenerating health was criticized by old-school shooter fans for removing some of the drama and tension that hit points represent. It's still enraging comment sections today.

Three games released in 2005 and 2006 all tinkered with ways of making regenerating health retain the sense of rising tension that hit points were first introduced to create. Condemned: Criminal Origins, Prey, and F.E.A.R. all set a floor on automatic healing so that if you take enough damage to fall below around 25% of your hit points you can't regenerate back above that line. It models a difference between taking a serious wound and the kind of graze action heroes can just walk off, and adds grit to more serious games.

Regenerating health was criticized for removing the drama and tension that hit points represent.

When the Just Cause games toy with this, only letting you regenerate a percentage of the most recent damage you take, it can seem at odds with their over-the-top action.

Horror games have also tweaked the way they use hit points to suit the genre. Zombie game Left 4 Dead slows you down the more you're hurt, making it harder to run away from the infected as if you're a movie character being worn down by the chase. In Silent Hill 4: The Room you regain health in your apartment, but when that safe space becomes tainted it stops healing you, a mechanical sign of its corruption that ensures you feel the same dread the character would.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Back to the source

Still, across all of these games, what hit points represent isn't entirely clear. Are they purely the injuries you endure, as the suffering face of Doomguy suggests? If that's true why is it so easy to get hit points back, whether through healing items or regeneration or drinking Fallout's irradiated toilet water?

In The Lord of the Rings Online hit points are replaced by morale, which explains why singing a jaunty tune helps top it up. In the Assassin's Creed games it's synchronization, a representation of how accurately your digital simulation is recreating historical events—although that raises the question of why being hurt during events where your historical analogue was also hurt doesn't improve synchronization.

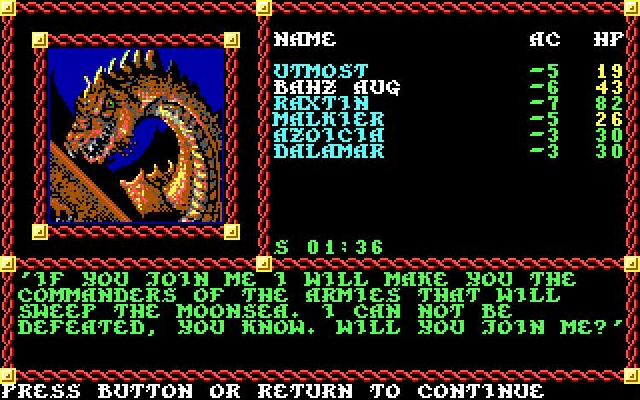

Even in D&D it's unclear what hit points really are. In the Dungeon Master's Guide for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 1st Edition, Gary Gygax wrote that hit points “reflect both the actual physical ability of the character to withstand damage—as indicated by constitution bonuses—and a commensurate increase in such areas as skill in combat and similar life-or-death situations, the “sixth sense” which warns the individual of some otherwise unforeseen events, sheer luck, and the fantastic provisions of magical protections and/or divine protection.”

(Charmingly, the rules then went on to explain that Rasputin would have been able to survive for so long because he had “more than 14 hit points.”)

Constitution, skill, sixth sense, luck, magic, and divine protection are a lot of things to bundle into one number, and raise further questions about why, for instance, poisoned attacks cause extra damage to your “sixth sense”. When asked about what hit points really are at conventions Gygax was dismissive, giving different answers to the question each time. Sometimes he said hit points represent the way swashbuckling movie heroes survive so many fights, or that they were an entirely meaningless number that represented nothing more than a way of making the game's combat more enjoyable for players.

That second answer is perhaps the best explanation. Given that hit points started out as a way of simulating the ability of a ship's hull to weather cannon-fire, it's only natural that there's going to be some vagueness and necessary abstraction when we apply that same concept to our video game heroes. They may as well be health pineapples, after all.

This feature was originally published in August 2016.

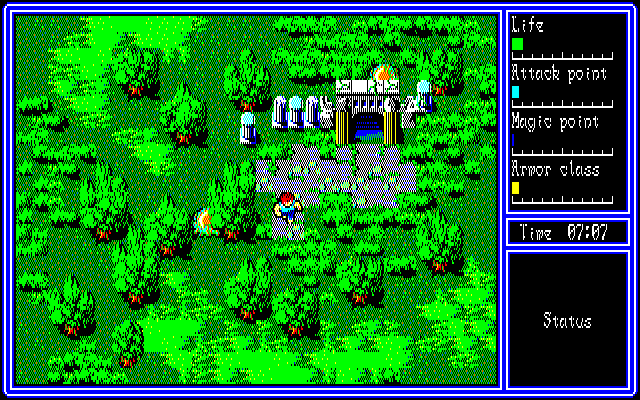

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.